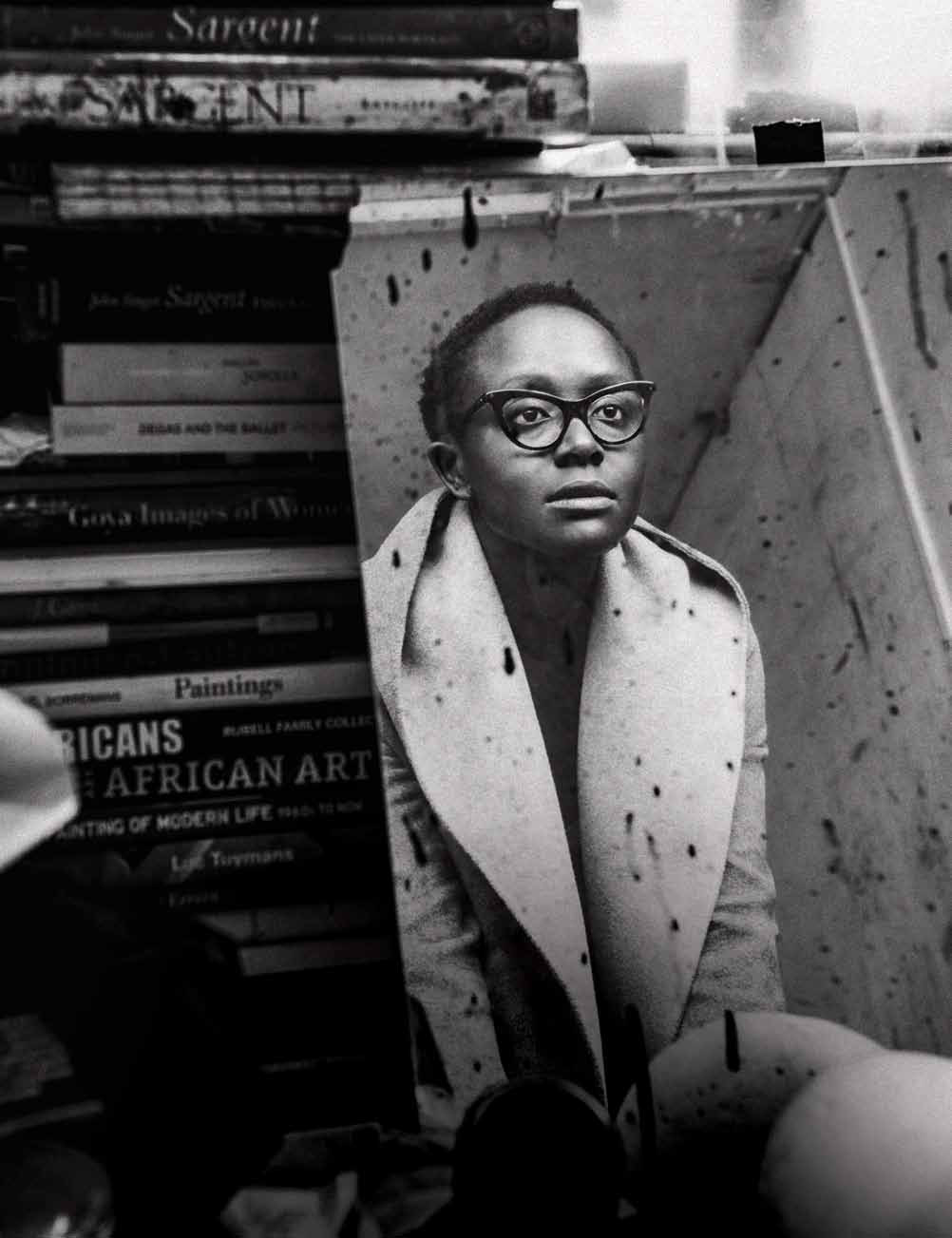

Lynette Yiadom Boakye

In the cramped Hackney studio of 35-year-old painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, there would be just enough room for a model to stand for the artist’s figurative oil works. Only Yiadom-Boakye doesn’t use a model. For the past decade, her growing cast of characters—predominantly black men and women rendered in a deft gestural realism so softly applied that the figures seem to materialize out of their muddy, color-field backgrounds—have sprung from her own imagination. “It kind of works its way as I go along,” Yiadom-Boakye explains. “I often have a vague idea of what I want the face to do, but it’s so hard to identify because I don’t want it to get too firm.” It is this lack of firmness that allows her canvases to excel at a quiet devastation. Unlike her contemporary across the ocean, Kehinde Wiley, who also forges a fraught black identity through the European model of portrait painting, Yiadom-Boakye doesn’t let her pieces become an accretion of pop-cultural references. Instead, her figures are cut free from place and time—dressed in simple clothes, inhabiting indistinct fields, even their expressions often falling between emotions. These haunting entities could have existed last week or last century—and, of course, in reality they never existed at all. “People ask me, ‘Who are they, where are they?’ ” she says. “What they should be asking is ‘What are they?’ ” Yiadom-Boakye was born and raised in South London, and her comprehension of European painterly technique stems from her studies at Falmouth College and the Royal Academy Schools (it is not surprising to think of Picasso’s painting of circus performers when considering the hushed emotional tones of her work). But Yiadom-Boakye’s intentional withholding of details or narratives seems particularly effective in our information-obsessed age, as if the artist is asking the viewer to help complete the fiction she’s begun. Many of her decisions are formal. “I tend to use red and white because they’re good for balancing,” she says of the choice of a red glove in one painting. “It holds it all together somehow and stops it from becoming too flat.” Yiadom-Boakye is even resistant to including shoes, because shoes are too indicative of time and place. The result of such minimal details is that what does appear on the canvas often resonates intensely. “When you don’t use shoes, your choice is either barefoot or socks,” she says. “At a show recently, a number of people commented that there were so many pairs of socks.”

PHOTO: LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE IN LONDON, OCTOBER 2012. ALL CLOTHING AND ACCESSORIES: YIADOM-BOAKYEÂ?’S OWN.