art

Lily Stockman Brings Us Back to the Gallery

Lily Stockman in her studio. Photo by Laure Joliet. All photos courtesy Charles Moffett Gallery.

Lily Stockman has always been a methodical artist, putting out a body of work that is both contemplative and disciplined. Like Agnes Martin and Dan Walsh, she focuses on the bare essentials: a steady hand pushing paint across the canvas, a carefully measured color, a monastic practice. Well, monastic as an artist can get with an infant, a toddler, and no babysitters, thanks to quarantine. Still, in preparation for Stockman’s solo show, Seed, Stone, Mirror, Match at the Charles Moffett gallery, the L.A.-based painter managed to steal some hours to complete her pieces before shipping them across the country.

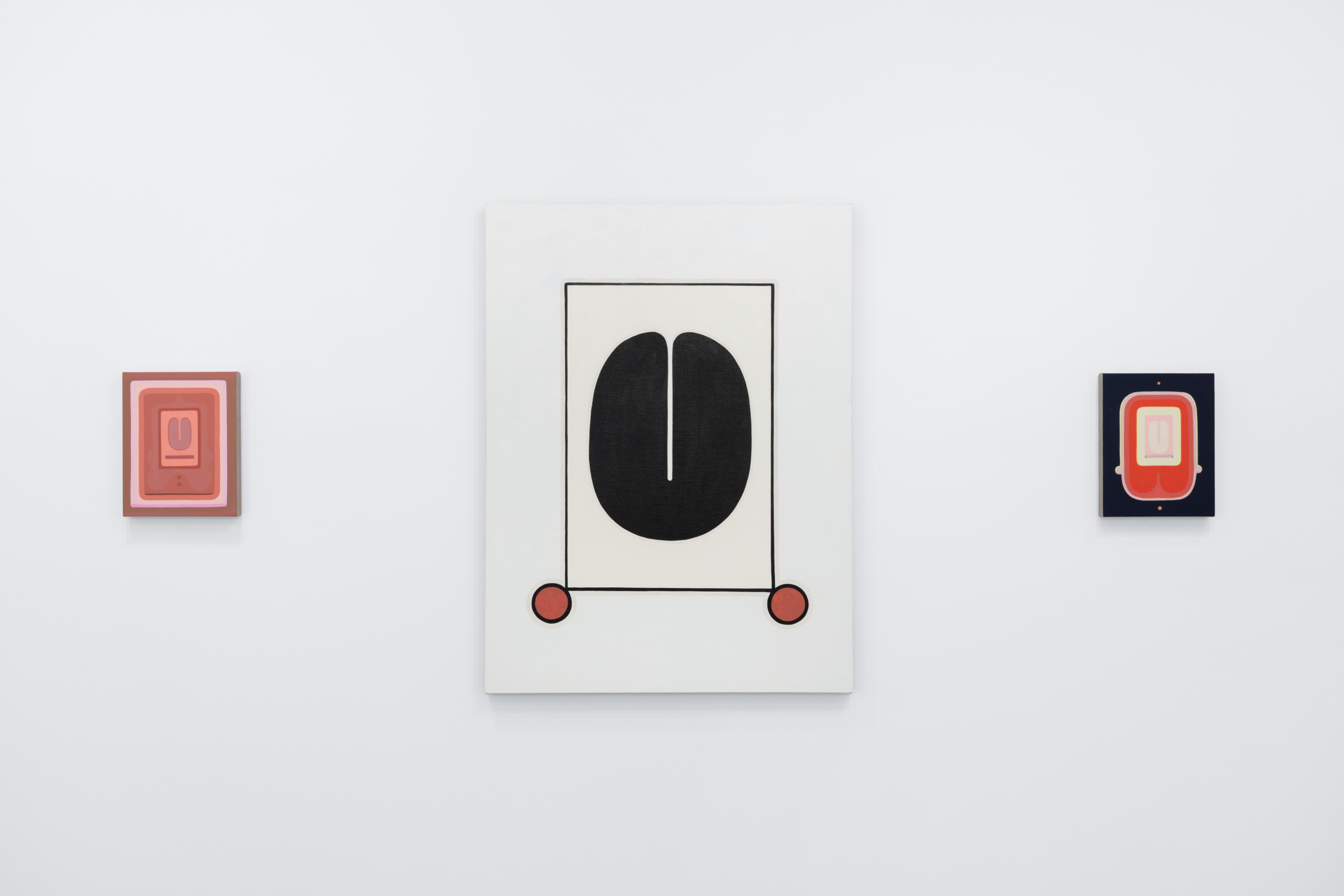

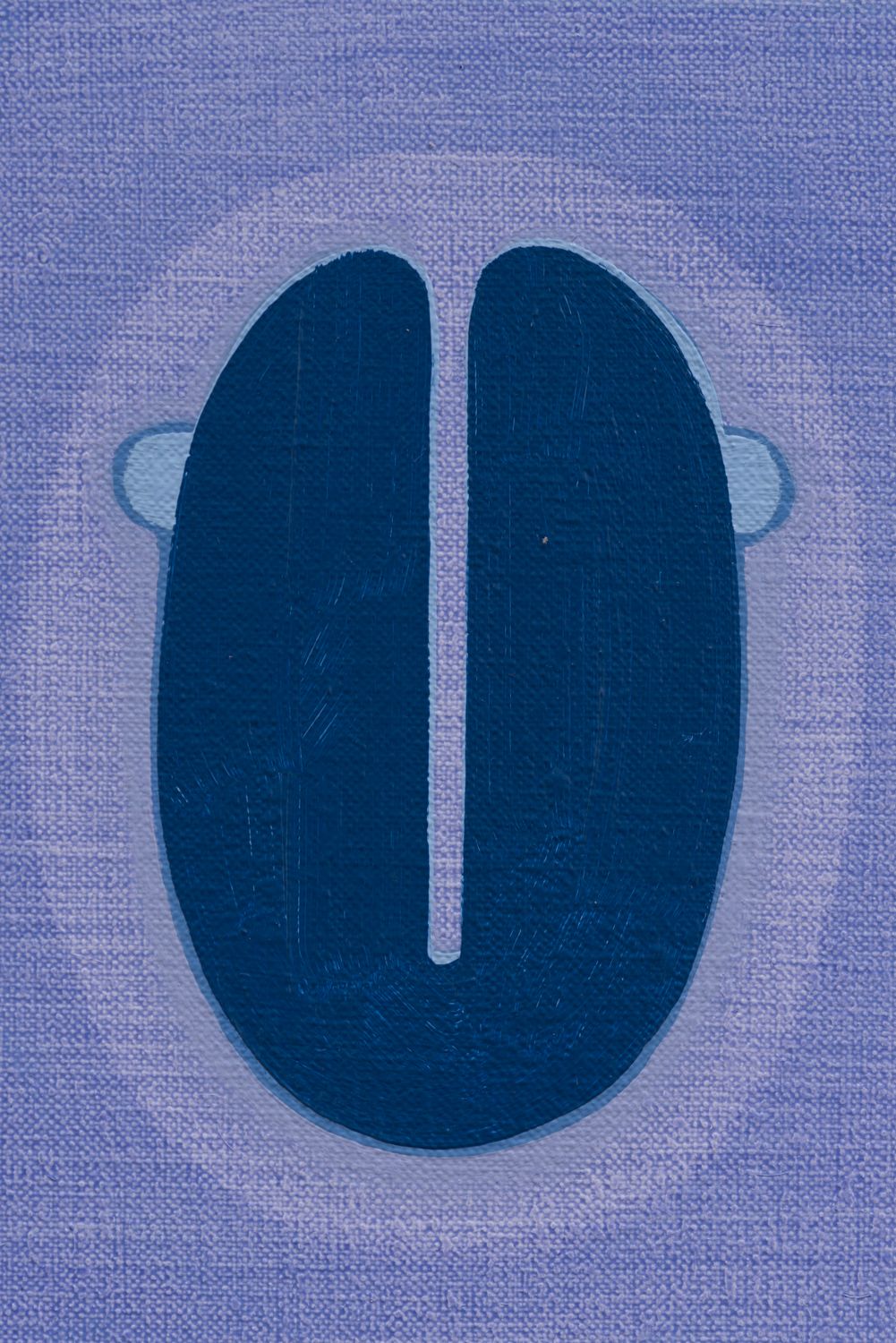

The gallery is modest, off the more industrial edge of Canal Street, but once you step in, the traffic sounds dissolve and we are transported into Stockman’s world of soft colors, primitive shapes, and rounded edges. Slightly graphic though never overwhelming, her work has a gentle, steady effect. Those who know Stockman’s work will find familiar shapes of the unfamiliar variety: the arch and its variant that looks like a coffee bean or beetle; the outline of a mushy brain; something like a slit; another that lies somewhere between a quill and a lightning bolt. In Stockman’s hands, geometry becomes somehow heavenly, organic. We spoke with the artist about her quarantine art practice, painting lines and circles in Rajasthan, and measuring time through plant germination.

———

SHANTI ESCALANTE: What’s it like to put stuff on gallery walls during quarantine?

LILY STOCKMAN: It’s been a blessing. My friend, Su Wu, who’s a poet and creator who lives in Mexico City, wrote this beautiful … It’s not quite an essay, but a prose for the show. We’ve been back and forth in this Google document writing about this poem that means a lot to both of us by Robert Haas. It’s called Meditation at Lagunitas, and it’s a great spirit booster if you ever need a little reminder of why we’re in the world of art. You understand after reading the poem a number of times that the ceremony of the poem is completed by you, the reader reading it. I think that’s such a beautiful way to think about looking at art in person right now. The ceremony can be completed with a stranger looking at the work in person, so that feels like a very sacred privilege, especially right now.

ESCALANTE: Can people come into the gallery?

STOCKMAN: It’s open regular hours and it’s just single appointments at a time.

ESCALANTE: That makes for such an intimate viewing experience. To go into a gallery or a museum and not just be crowded out.

STOCKMAN: Doesn’t that sound so nice? I remember having that feeling in the Guggenheim. I saw the Hilma af Klint show around Christmas and it was so packed. As magisterial as it was to see all of her work in the temple of the Guggenheim, it was also so frustrating because it was so packed and the little galleries are so tight, you can never back up far enough to really take in the horizon of these paintings. I remember feeling hopeful that there would be another show in our lifetime that would have a little more space and privacy.

ESCALANTE: I know that you were painting during quarantine, and you were also painting as you were taking care of your infant child. Can you tell me a little bit more about that experience?

STOCKMAN: The show has been planned for a year, so I’ve been working towards it. But it takes me a long time to cast a wide net and pull up the fish of inspiration and see what the best ideas are. I wasn’t really hitting my stride until February. And at that point, my baby was just a couple of months old and I also have a toddler. The two- year-old was in daycare and then I had an infant and then L.A. shut down and suddenly we had no childcare. It was just me and my husband, who is also self-employed. We just kind of made due, and I felt so frustrated in the beginning, obviously keeping everything in perspective of how incredibly lucky and privileged we were at the same time to be healthy and to be able to keep our jobs.

But, I wasn’t able to go to the studio for quite some time. And so after we’d get the kids down at night, I drew. With drawing, I’ve always felt like an out-of-practice musician, kind of not really doing the scales. It was always nagging me in the back of my head that I needed to be drawing more. In retrospect, I guess it was this gift, but I just had to completely strip down my entire practice to just colored pencils and paper. We have this tiny little postage stamp garden behind our house in L.A., and that’s really where I could put my creativity.

ESCALANTE: Do you enjoy gardening?

STOCKMAN: Yeah. I’d have the kids out with me, and we would be planting radishes that germinate really quickly. I was thinking of measuring time through what we were growing in the garden. It’s just a beautiful new way of noticing for me, which was being on a very small, particular scale of their little worldview and noticing the world of insects that we were living with, but don’t really think about. And the radishes sprout really quickly, to the glee and surprise of my two-year-old.

My mom sent me a bunch of Dahlia tubers from her farm on the East Coast. I planted those at the very beginning of quarantine. And now, here we are in September and they’re five-feet-tall, covered in these huge dinner plate-size blooms. The garden has been this really profound way of measuring time in a way that I don’t think I would have appreciated before. I’m not the only one who’s found solace and comfort and understanding through being in the dirt, but it’s certainly a way that helps me understand my place in the world and my responsibility in the world, which is spending time weeding and watering.

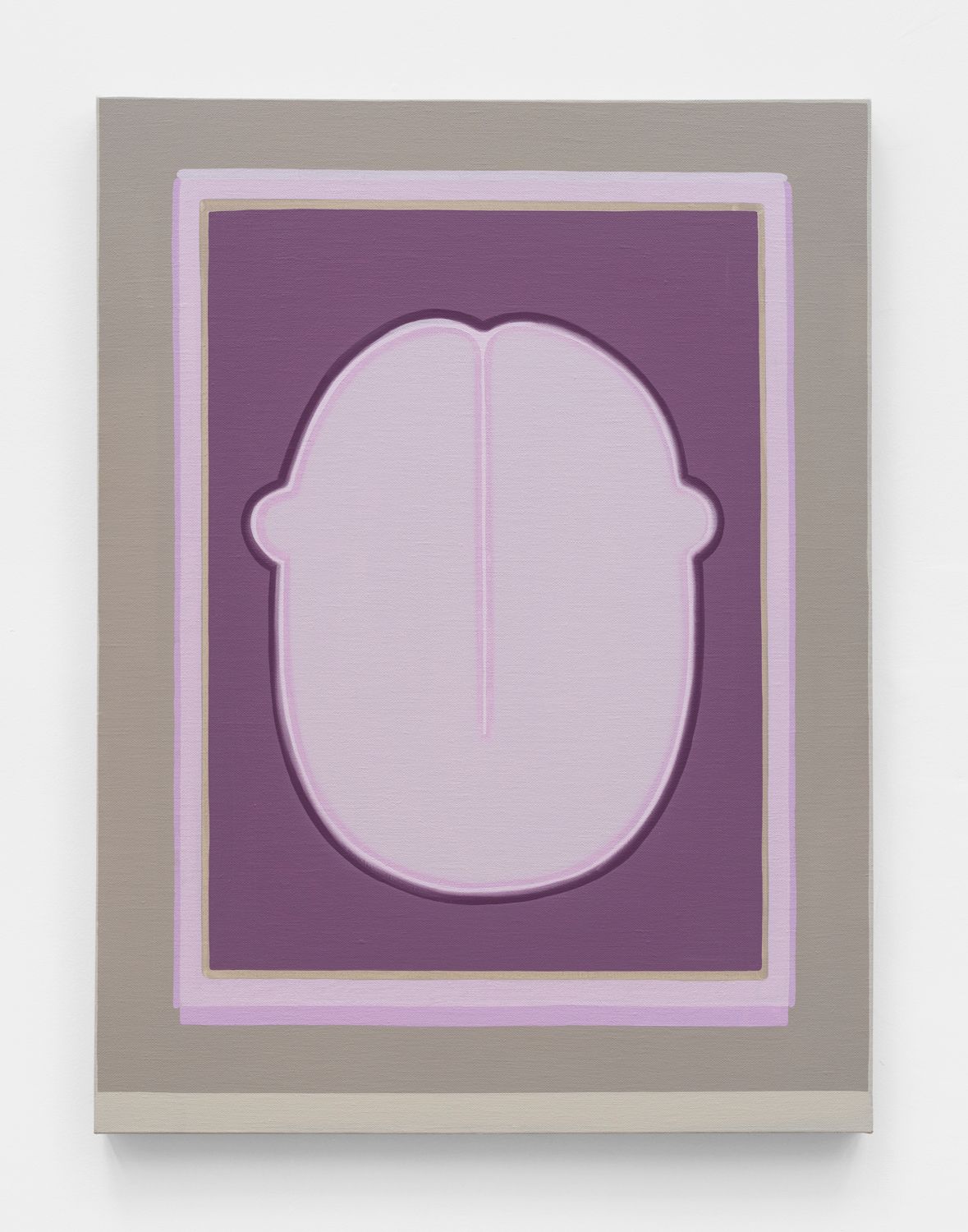

Float, 2020.

ESCALANTE: How has your relationship with your environment affected your painting?

STOCKMAN: I grew up on a small farm in New Jersey, so I always had a nerdy naturalist’s sensibility, I guess.

That was encouraged early on in my education. I had this incredible professor named Nancy Mitchnick, who ran the painting department at Harvard and wouldn’t even let you walk in the painting studio, unless you’d taken Art History and a fresco class and spent time at the Fogg Museum.

I remember in both my botany class and Nancy’s intro to painting class going into the dimly-lit dusty old oak halls of the Peabody Museum and drawing the glass flowers. And then Nancy taking us out to Ipswich, which is this little beautiful windswept place an hour outside of Boston to pick crab apples. I think we were just trespassing around on this little state park or something, but she had everyone gather all of these arrangements and then stage all these wild still life paintings based off of Flemish Golden Age still lives. There was a lot of rich resource material as an undergrad for painting from the natural world.

ESCALANTE: You grew up on a farm? What was that like?

STOCKMAN: Growing up, I spent a lot of time helping my dad mow hay. My parents grow Alfalfa. My sister pointed out that the rounded borders in my paintings are like the hayfields, because with a big mower, you can’t mow a perfect 90-degree angle. The architectural term for that soft curve, that top of an arch, is called a spandrel.

Millard Falls, 2020.

ESCALANTE: You have a lot of repeating shapes in your work: the arch, the coffee bean-type shape. Where do these symbols come from?

STOCKMAN: I’ve been painting arches for the past couple of years. Those came from spending a lot of time in Rajasthan. I lived in Jaipur for a while before grad school and then go back, usually every year or so, to see friends and the architecture. You become very aware of the softness of being in architectural space with arches.

When I moved to L.A. after grad school, like seven years ago, I had a studio downtown. I don’t know if you’re familiar with downtown Los Angeles, that there are all these wonderful old mashup of Art Deco architecture and the Angeleno version of French glass and steel construction arcades. If you pause and look up, you realize these beautiful architectural elements like flying buttresses, which are holding up these big interior arcades. My paintings are relatively flat, but they have these color harmonies or these little suggestions of a shadow, and then the arch is this invitation into the next little plane of the painting. That’s where the artists come from.

Especially after having my second kid, I was back in the studio and I was searching for something that felt like something you could hold in your hands, that could then be placed inside the little window of the painting, like a Joseph Cornell box. Like, this is the egg that gets to go in the nest and then it sits there.

So I closed up the arch almost entirely, except for this little slit, basically. I was careful not to put a name on it, but a couple of months ago is when all the scarab beetles hatch in L.A. Wild week. You just have these two-inch iridescent green beetles that seem to be out of some other dimension. Another way of noticing time is through this cycle of the insects. And so, I guess it’s truly a scarab beetle shape, or a coffee bean, or a sinker that you would put on a lure if you’re fishing.

- Digitalis, 2020.

- New Dahlia, 2020.

ESCALANTE: Yes, the beetle shape is very tactile, graspable. I also noticed that you’re been painting on a larger scale recently. What prompted that urge?

STOCKMAN: There’s something really appealing about working on a very small scale and working on a table and having this quiet, small mobility around a surface like that. But the big paintings felt like there’s wonderful relief from being cooped up with two kids, a small house and having all of us going out to protest and then coming home and hearing what’s coming out of Donald Trump’s tweets. There is something about having this athletic release and pursuit, but also focused energy that can go into a really big painting. That’s what I’m working on next, these large-scale paintings.

ESCALANTE: And you do all of your lines by hand?

STOCKMAN: Yeah. When you see [the paintings] they look really graphic and flat as JPEGs, which is how most people see paintings these days. But I hope that when you see them in person, you’ll realize how wobbly my hand gets, or you can see where I exhale or take a breath in there, or if I’ve had too much coffee and there’s a little movement in the hand. I think that’s really important. I remember the beautiful Roberta Smith review of a Dan Walsh Show maybe 10 years ago. She used this term “the vagaries of the hand.” I love having this pejorative word like vagaries with the hand and how poetic that was. His line is so steady even though he is using this very thin paint so that you can see the pressure of the brush and the spring of the brush lifting the paint off the surface with the bristles. Seeing those paintings and actually understanding them better through that beautiful term of phrase, I think helped me understand why I wanted the lines to be imperfect.

ESCALANTE: Agnes Martin obviously comes to mind.

STOCKMAN: I find it so moving that she worked in a six-by-six foot scale at the heyday of her art-making until towards the end when they got a little bit smaller. She was very old and it was harder for her to make that reach. I love that she was still in control of how her body, and her arm, and her brush related in that one beautiful movement in the pulling of the line. There was a period where, or a moment where she realized, okay, I have to make these a little bit smaller so I can keep the tone working. I think the paintings from the end of her life were like five-by-five feet.

In the studio with Stockman. Photo by Ed Mumford.

ESCALANTE: Tell me more about your time in India. How’d you end up there?

STOCKMAN: There’s a painter there named RJ Sharma who has an Indian miniature painting school. And so I just worked with him again, grinding pigment and burnishing paper to get the really smooth surface for Indian miniature painting. And that was working with the squirrel hair brush. So that’s eight little squirrels and it’s very precise. There’s this whole rich history of working your way up into image-making. And I was just, like, the lowly student. The whole time, I just made lines and circles for him. So that’s what I learned from RJ: how to make a really straight line and how to make a pretty okay circle.