The World According to Karen Finley

Karen Finley had already made a name for herself as an artist in San Francisco when she moved to New York City in 1983. I remember her arrival on the East Village art scene—all of us do—because her work instantly stood out for its bravery, punk-rock vitality, and breakthrough radicalism. I saw her perform on stage at the downtown club Danceteria one night in the mid-’80s and was blown away by her ability to inject passion, humor, honesty, and aggravation into one of her signature monologues, set to a disco beat. Finley has always been able to turn up the temperature of the room to boiling. Of course, it wasn’t just New York artists who took notice of her raw, uninhibited performance works, which covered politics, sex, and feminism, and which often involved her stripping down to her bare skin. In 1990, in a piece called “We Keep Our Victims Ready,” she famously smeared chocolate on her nude body at Lincoln Center to prompt questions about sexual violence and the degradation of women. Soon after that, Senator Jesse Helms went on a full-scale attack of her work, and that of three other NEA grant recipients, leading the National Endowment of the Arts to rescind her grant with the charge of “indecency.” This attempt by Washington to censor the arts forever changed the structure of public funding in the United States. Over the next eight years, Finley fought her way to the Supreme Court. She lost that suit but championed the freedom of artists and their voices and bodies the entire way. (She even posed, covered in chocolate, for Playboy in 1993 to draw attention to the hypocrisy coming out of the nation’s capital.)

Finley was an early pioneer of interdisciplinary art, working as she did in performance, music, graphic texts, sculpture, installation, poetry, and drawing—all in the spirit of a public conversation. In 1990, she mounted her poem, “The Black Sheep,” cast in bronze right at the corner of Manhattan’s First Avenue and Houston Street. “We are the sheep with no shepherd,” she wrote. “We are the sheep with no straight and narrow. We are sheep who take the dangerous pathway thru the mountain range to get to the other side of our soul.” This was the first time I had witnessed an experimental artwork taken seriously by the general public. Everyone who rode the subway on the Lower East Side engaged with her piece, and we were its subject—all of us who came to New York City in the late 1970s and early ’80s looking for a place to belong. We had, she was telling us, found it.

Today, Finley’s voice rages on, whether she’s tackling Trump and right-wing America in her performances, eulogizing the friends she lost to AIDS, or teaching performance to a new generation of New Yorkers at NYU. I have always thought of her work as a kind of panacea for society. It’s fitting, then, that we met at a place called Remedy Diner on Houston Street to have this conversation.

———

Finley photographed by Midge Wattles in the Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York.

KEMBRA PFAHLER: You’re so prolific. You have an art career, a family, and an academic life teaching at NYU in art and public policy. Social change through art is something you’ve had actual experience with—the litigiousness of having your own art criminalized.

KAREN FINLEY: Well, after I lost the NEA case in 1998 with the other three artists—Holly Hughes, John Fleck, and Tim Miller—I had to look at other ways to make a living. My artwork was being sent back from museums. I didn’t have the ability to show or work at places that depended on funding. That’s how I ended up going into teaching.

PFAHLER: My feeling has been that you actually won the NEA case because it raised the consciousness of what performance art was. Most people didn’t even know about performance art until you started articulating and showing it, and fighting for it.

FINLEY: Sometimes you win by losing. The lawsuit wasn’t about whether or not we should get grants. It had to do with the language surrounding the notion of using decency to award federal funding. We claimed that the language was vague, and that’s what we lost on. But that set a precedent in terms of thinking about the notion of decency in so many other matters of funding, whether it’s education, sex education, libraries, or issues of federal funding with Planned Parenthood or immigration. And even with what’s happening now in terms of museums and the relationship between private and public funding, like what you’re seeing with the Sacklers.

PFAHLER: It wasn’t even that much money you received for the grant. But, as you said, it affected your ability to make a living as an artist.

FINLEY: And it changed the access. I mean, maybe I would have been making those decisions anyway about where my work was going to go, whether I’d stay in art or move into a more commercial sphere. I feel like my strength—or what I get off on—has always been in innovation and experimentation.

PFAHLER: Do you think the art world got spooked after your court case?

FINLEY: Yes. And I think it’s one of the reasons that museums are in the position they’re in. Most corporations or institutions are going to be fraught with dirty money. This is a general statement, but my feeling is that it’s important to look at what happened 20 years ago. Because of that loss, museums and institutions had to start looking for private money—often corporate money—for support, rather than depending on public funding. So museums started to lean more toward private philanthropy. And now we’re in the situation we’re in.

PFAHLER: And private funding is very conservative. The United States is supposed to be a leader of art and culture, and yet we don’t have a Minister of Culture. I think I’ve learned more from talking to other artists than I have from reading the newspaper. Your work in particular transmits the spirit of the times in a way I can understand. It’s tragic that this country believes so little in that kind of art, and that we don’t give money to our artists. It’s a tragedy.

FINLEY: Especially when there are so many incredible artists out there. I mean, why do we live in New York? It’s this belief in the value of artistic expression. And as to what you’re saying about using artists’ works to understand the news, that’s a really old concept—the artist as historical recorder. Since the beginning of time, artists have produced the documents of their age, and I like to think of my work that way.

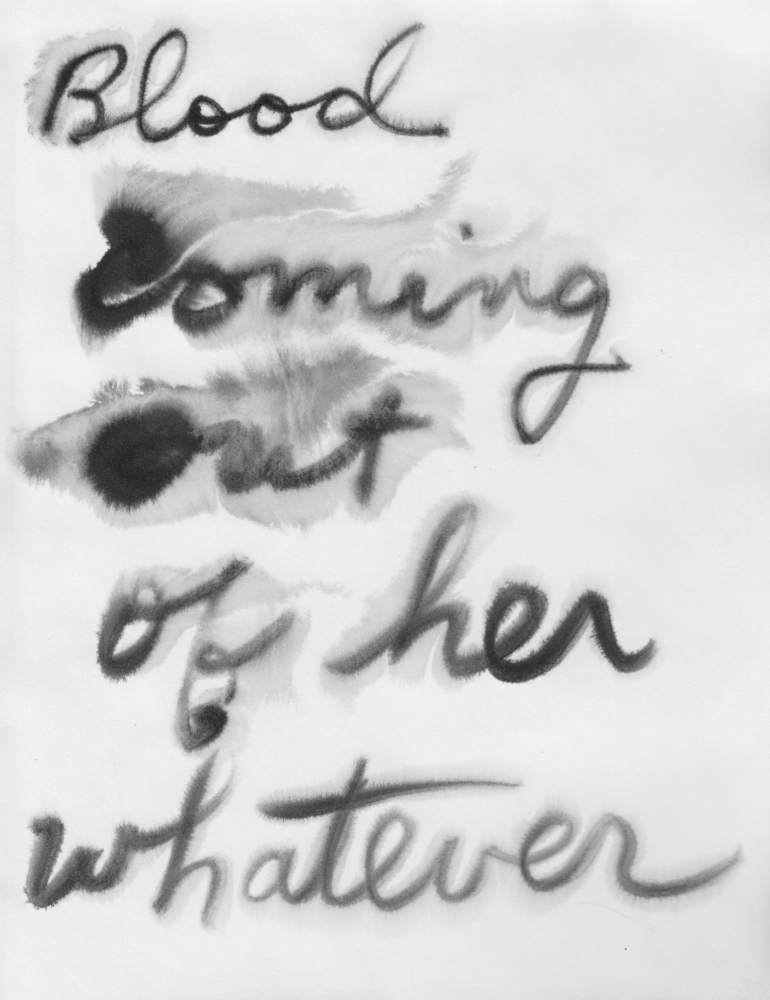

From “Shut Up and Love Me!,” 2001. Photographed by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders.

PFAHLER: The first time I saw you live was at Danceteria. You had just come from San Francisco, where you were involved with the punk rock scene there. At that time, in the punk rock scene of the Lower East Side, we were just learning what your kind of performance was about. You were the first. The show was packed. There were thousands of people at Danceteria—just wall-to-wall. Your piece was less than ten minutes, and it was just you on stage. I remember the whole energy of the audience completely flipping when we heard you. Your voice, your mannerisms—it was an incredible performance.

FINLEY: You also saw me do a performance at the retrospective for your friend Gordon Kurtti (an influential East Village artist and performer who died of AIDS in 1987).

PFAHLER: That was such a great show. It was the 25th anniversary of Gordon’s passing. He was my first friend in New York. I still have an intense feeling of trauma from his death. I think about him every day. And your performance was amazing.

FINLEY: I collected all of my performances and writings on AIDS, and read some of them for Gordon’s exhibition. That’s something you and I really share: we came here at this specific time in history that had so much promise. But around that time the AIDS crisis was going on, and so much of this work, so much of the reason all of this censorship was going on as well, had to do with homophobia. People talk about Trump and say, “Oh, it’s so horrible now.” I mean, what year was a good year? Yes, it is horrible right now with Trump. But was 1988 a good year? Was 1986? Was 1969 a good year? That is another part of the artist as historical recorder. There have been horrible years before. But it’s also the artist’s job to inspire and empower people to move on to the next step.

PFAHLER: There’s a lot of revisionism happening with this kind of yesterbating about the ’80s, romantically historicizing and having nostalgia for that time. Yes, New York in the ’80s was alive with fun and frenzy. But it was also like living through a holocaust that changed our lives forever. And I agree with you—what year was good? Today, though, I do find that people are really isolated. They’re spending a lot of time in their bedrooms with their computers. They stay indoors and engage online. I don’t have a computer, but I’m aware that I’m complicit in my civil rights being violated every time I pick up my phone.

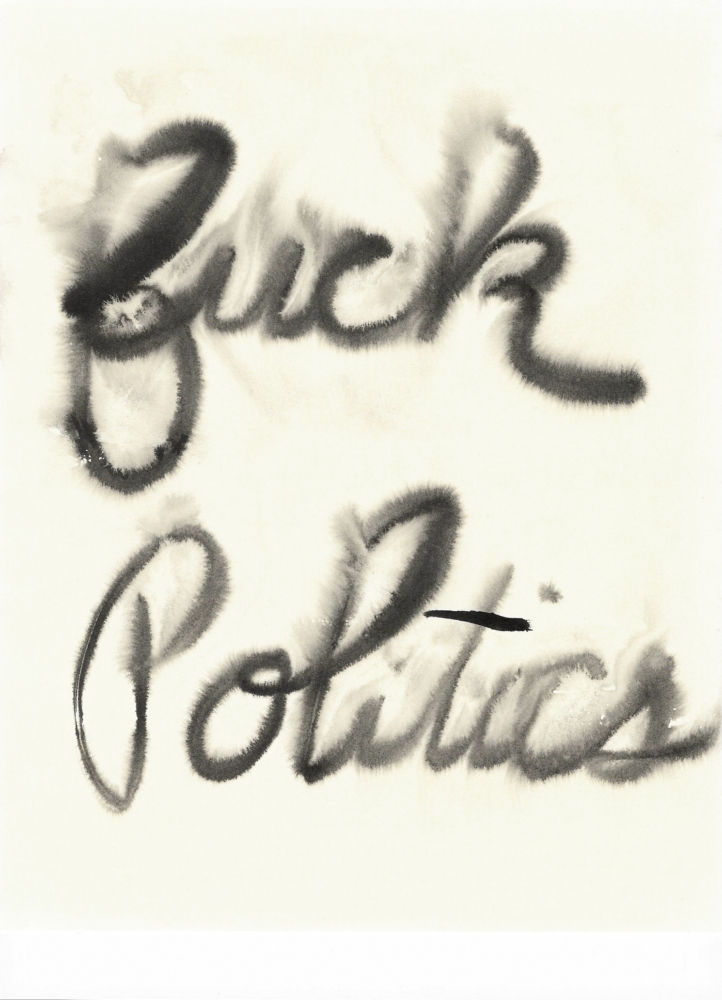

“Fuck Politics,” 2018

FINLEY: I think what people have to understand is that this is not intimacy. Or maybe it’s a different type of intimacy.

PFAHLER: People seem to have forgotten how to speak to one another.

FINLEY: I think that’s why I still love performing. People are seeing my physicality. I’m seeing theirs. I’m picking up their energy. We’re breathing the same air together, and it’s so important to do that. I recently started a group called Artists Anonymous. We have 13 steps. We just get together to talk about our issues or concerns.

PFAHLER: I would love to go to Artists Anonymous.

FINLEY: You should come. I’ve been thinking about the legacy of Andy Warhol lately. I’m old enough to remember seeing him out. I worked in places he would come to every night when he would be out with people looking and noticing, and just being in a room together.

PFAHLER: And having the willingness to make mistakes in public. I think that one of the reasons why folks don’t come out of their little shells anymore is because things are so overly documented. Anything you say, or how you’re looking that day, is going to be recorded or photographed. They almost have performance anxiety about showing up in life.

FINLEY: Or not responding correctly. If you’re an introvert, which I am, sometimes you take longer to respond.

PFAHLER: Before New York, you were out in San Francisco in the late ’70s. Is that when you started doing performance work?

FINLEY: Well, I grew up in Chicago. I had been doing performance and was aware of conceptual work early on as a child. I had an understanding of it from junior high, but I started to do it more in high school.

PFAHLER: We’re about the same age. And yet, I remember thinking when I first saw your work how evolved you already seemed as an artist. I was still struggling to find my identity and it took me a couple of decades to really feel like I was a performing artist. You were very ahead of your time.

FINLEY: Thank you for saying that, but I didn’t necessarily feel that way—and that self-doubt was likely gender-based. I had very few women mentors.

PFAHLER: Other women in the art world weren’t kind to me. You were. And that was very unusual in the ’80s. I felt sort of frowned upon and judged. But you were so supportive before it was popular and cool to be a supportive female. I remember you checking in saying, “Are you all right? How are things going?” That was really life-changing because it was a hard time and I lost most of my friends to AIDS. It was around the time that you installed your text piece “The Black Sheep” by the First Avenue subway.

“The Black Sheep,” 1990. Photo by Michael Overn.

FINLEY: The writing of “The Black Sheep” came out of the horror of the time and was specifically about AIDS. But it was also a prayer for the outcasts in society. I wish that sculpture could still be on display in New York.

PFAHLER: Me, too. Especially because AIDS still exists. It articulated the relationship that the people who were dying had to those who had abandoned them. That was the essence of the piece for me, and it was something no one ever really spoke about: identifying the hideous villainy of the family.

FINLEY: The family can be one of the most painful places. The people who are supposed to be the closest to you can, of course, be the cruelest. I wanted to address that trauma.

PFAHLER: You’ve always unearthed taboos that people are afraid of discussing. Do you feel that there has finally been a systemic change in addressing these subjects?

FINLEY: When I started in the art world, there was feminist art being made. There has always been work dealing with political and social issues. That being said, the art market of the time was about minimalism, and what was exciting about the East Village was how it disrupted or subverted the market. That was my aim, to subvert the art world and expand the spaces allocated to cultural expression. Since we’re talking about censorship and my position in the art world, I also feel that I was very, very privileged by being a white woman. To think that I was valued enough by society to even be censored. There were many people who weren’t given that position, who weren’t even allowed to be censored as I was. That’s not to say that censorship is good. But as you were talking about nostalgia, I look back at that time in the East Village, the whiteness coming into that neighborhood and taking over the tenement apartments, as a form of colonialism.

PFAHLER: Totally.

FINLEY: The artists in the art market were basically white kids from a certain economic sphere and education, and that was in itself an undervaluing of the culture. I have, too, some accountability for that as part of that generation. This isn’t something that just started with Giuliani or Bloomberg. This has been happening for a long time, and I was a participant.

PFAHLER: Me, too.

FINLEY: I can’t really say that I was a victim in terms of the censorship. Yes, I had death threats, but I was also part of a system. I look at it differently than I did in 1990.

PFAHLER: Artists always come in and we decorate, and then the prices of the apartments go up. Art changes commerce in a neighborhood. I’ve found that the Puerto Rican and Dominican people of the East Village, they saved me, because all the Santería music became such a big part of my work. That’s what I got out of this neighborhood that I think has been very much ignored.

FINLEY: That’s absolutely true.

From “We Keep Our Victims Ready,” 1990.

PFAHLER: So what about your upcoming projects? I know you’re doing a performance this spring at MoMA PS1 timed to their exhibition on art from the Gulf War.

FINLEY: The show is called Theater of Operations. I have a wall text that’s up and some drawings. One is of the execution of Saddam Hussein. I’m doing a performance on “The Dreams of Laura Bush.” For this piece, I created her dream journal.

PFAHLER: You also did a book on Trump. You’re taking on the administration!

FINLEY: That book is called Grabbing Pussy. It’s about the times we’re living in, from #MeToo to the election. I do it as a poetic text. I should have brought you a copy.

PFAHLER: I brought you a vagina t-shirt! It’s from a film I made with the photographer Richard Kern, where I sewed my vagina shut. It was a long time ago. I didn’t hurt my vagina or anything. I just did it for the film.

FINLEY: Well, David Wojnarowicz sewed his mouth shut.

PFAHLER: And then Madonna just did that with her Madame X album cover—a fake sewn mouth. She’s such a cultural appropriator, Madonna. She should give back to this neighborhood. She and Lady Gaga should buy buildings on the Lower East Side, the place they’re always saying made them, and give the buildings to artists and to the locals. They’re so rich. People never give back to the Lower East Side. Last question: Would you get into politics?

FINLEY: No, I’m an artist.

PFAHLER: What about being the Minister of Culture?

FINLEY: I’m too much of a narcissist. I’m not willing to give up my own practice. I love making art.

This article appears in the March 2020 issue of Interview magazine. Subscribe here.