Josephine Meckseper and the Burden of History

Josephine Meckseper is adept at critiquing her environment. She questioned the prosperity of the art world by placing an “Out of Business” sign in the window of a gallery in Chelsea (a similarly cheeky “Help Wanted” sign attracted up to 20 applicants a day who had failed to get in on the joke). In 2012 she erected two 25-foot oil rigs in the heart of Times Square to remind unsuspecting tourists about the perils of capitalism and industrialization. Her work critically examines mass media, our consumption-obsessed society, and even our political systems. But for her most recent solo exhibition at Andrea Rosen in Chelsea, Meckseper turned her attention towards something left previously unexamined: her own lineage.

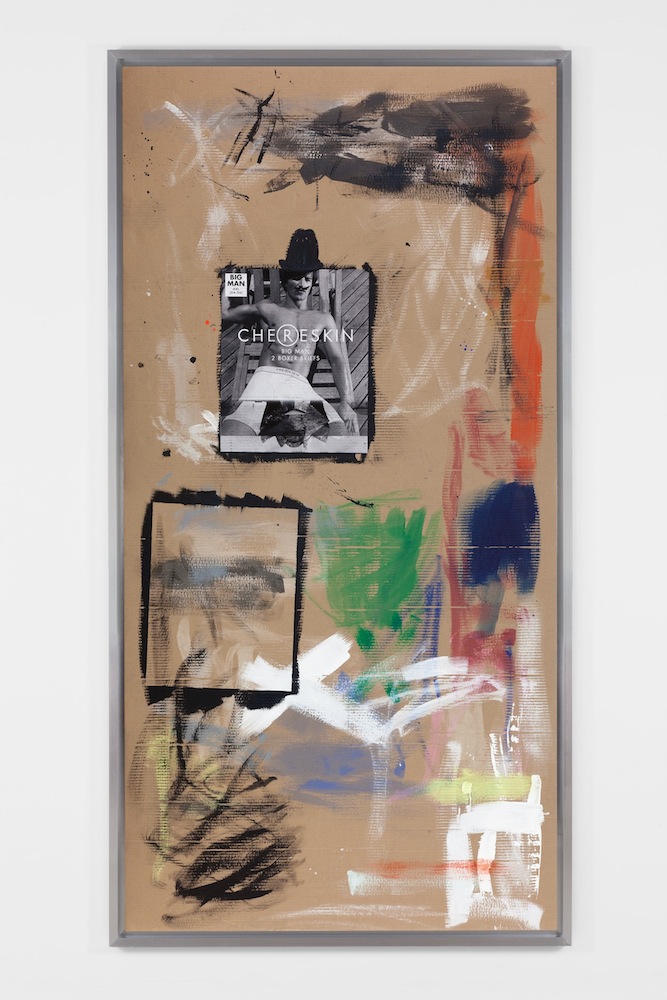

Though Meckseper left Germany for New York on her own accord, she failed to leave behind the burden of guilt felt by many young Germans, even three generations after World War II. The reverberating impact of Meckseper’s German heritage is exemplified by her black-and-white images of Niedersachsenstein, a sculpture in Meckseper’s hometown of Worpswede that commemorates the soldiers who perished in World War I. This historic image is juxtaposed against glossy ad images and Meckseper’s vitrines—recognizable reconstructions of modern store displays. The uniquely personal nature of the exhibit became clear when we sat down with Meckseper to discuss leaving the sheltered artistic community of Worpswede, living in New York, and the Christmas displays at Macy’s.

ALLYSON SHIFFMAN: There’s a sense of irony in that the advertising imagery in this exhibit closely resemble the ad pages one would find in an issue of Interview. Do you have any misgivings about that?

JOSEPHINE MECKSEPER: That’s funny—no one has ever asked me that. Obviously my work speaks to the usage of advertising. The abstractions in my paintings were actually based on how you divide an advertising page—the quarter-page, half-page ads. Since it’s so much a part of what I’ve been doing, it’s good to embrace the media rather than try to ignore it.

SHIFFMAN: Worpswede seems to be this sheltered artistic utopia. At what point did you start to become aware of the world beyond this community?

MECKSEPER: I moved to Tuscany right after high school, which was actually not very different in the sense that it was extremely sheltered and very much formed by cultural history. There was little mainstream contemporary consumer culture there, at all. Then I was briefly in Berlin studying at Berlin University of the Arts, but Berlin was so underground at that time. The wall was still up, so it was much more about being in this island inside of East Germany. I was completely in favor of the division of Germany—it’s kind of a leftist stance. We all felt it was not justified that it would ever be unified.

So it was really only when I moved to Los Angeles to go to CalArts—that was the big shift for me—to be outside of L.A., in Valencia, where it’s all about the mall. That was the beginning of deciphering the language and the vocabulary of the mall and the culture that comes with that.

SHIFFMAN: That’s an extreme introduction to consumer culture—especially at a time when the mall was still very relevant. It’s evident in your film that explores the Mall of America that mall culture is waning. Does this amplify the quality of relic in your work?

MECKSEPER: It does. The whole idea of the window displays is already becoming something very historicizing. It’s more about looking at something that’s disappearing in our culture. There was a time that the Christmas decorations on Fifth Avenue were a big event—people would come from the suburbs. Now I can imagine a young kid saying, “There’s no way I’m going to go to that.” [laughs]

SHIFFMAN: [laughs] To anyone who isn’t from New York, the notion of unveiling the Macy’s window displays being an event is so peculiar. Is your studio still in Chinatown?

MECKSEPER: It is. It’s near Orchard Street on the Lower East Side, where there are still some of the older Jewish shops. There’s this one lingerie store that has extra-large women’s underwear. So there’s literally these huge underwear displays… nobody now would display something that is that unattractive. It’s pretty surreal.

SHIFFMAN: This show encompasses so much more than the consumerism issues—particularly with the images of the Niedersachsenstein monument in Worpswede. What did that monument mean to you growing up?

MECKSEPER: I always liked to make up stories and narratives. I would bring other kids there and tell them all kinds of stories about what I thought it was.

SHIFFMAN: Can you recall any of these stories?

MECKSEPER: A lot of the fantasies revolved around us having been told that after the war a family had to live in the basement of the monument because there was no place else for them to stay. They had come from the East, fleeing from the Russians. During Fascism the monument was declared degenerate art and it was supposed to be torn down. In the 7os when we were going there, we didn’t really see it as artwork as much as a place for us to hide. We also tried to break in to see how they might have lived in there. It’s tucked inside of a forest and when I grew up people didn’t really want to go there. People would rather try to forget about it-nobody wanted to be reminded of the war at that point. Now it’s slightly different.

SHIFFMAN: When I first visited Germany, I was overwhelmed by the burden of guilt felt by young people and all the monuments built to serve as reminders.

MECKSEPER: It is. It’s huge.

SHIFFMAN: How do you approach doing a show in New York, in Chelsea, differently? Are the stakes higher given this is essentially the most consumerist of cities?

MECKSEPER: All my previous gallery shows that I’ve done here were hinting directly at that issue. It’s so much a part of my practice to be conscious of the environment. It goes back to being at CalArts and studying with Michael Asher, where it was really about institutional critique, but this show is a lot less about that. Chelsea is so oversaturated, it’s not that interesting anymore. So it was an opportunity for me to dig deeper into what it means to be a German artist in New York.

SHIFFMAN: And what does that mean?

MECKSEPER: It’s sort of what it means for me having come here without being forced. That whole guilt thing was so heavy on me—when you’re really sensitive, you can’t live with it. It was actually unbearable to stay [in Germany] and be constantly reminded of it. I’m the third generation after the war, so it feels selfish for me to say that I’m somehow affected by what happened, but it’s still so much a part of my life. This is the first time I felt like I’m actually bringing that into the work. Of course there’s all the consumerism, but there’s also another truth, which is more biographical.

SHIFFMAN: Your work has also touched on issues surrounding the oil trade. I’m curious about what your thoughts are on the emerging art scenes in oil rich countries like Qatar?

MECKSEPER: There are very different aspects to it. When I was in the United Emirates participating in the 2011 Sharjah Biennale, even though they censored some of the works and they fired the director of the museum, it was such a great opportunity to begin opening up that society. I was in this building near the main museum that was next to a mosque. People would go to the mosque and they would stop at the museum afterwards—I don’t know if it was because the AC was running [laughs], but it seemed very organic. It was actually providing opportunities and jobs in and around the museums, especially for the local females interested in art. So I’m actually for it.

SHIFFMAN: So what else have you been working on?

MECKSEPER: I’m working on proposal for a competition to create an outdoor environment at a prison in Germany. It’s in Stammheim, which was the prison for the Baader-Meinhof Group—the German terrorist group from the ’70s. My aunt was sort of on the fringes of it.

SHIFFMAN: That’s fascinating. How does a competition like that even come to exist?

MECKSEPER: The Green Party is running the state where the prison is, so they have all these innovative ideas. It’s a very, very unusual project.

SHIFFMAN: Everything you do has such weight to it. What do you do to relax or escape?

MECKSEPER: I don’t really do anything to relax and escape. If I could take a vacation that would be great, but I never do. [laughs] I like badminton. I never have time to play, but when I do, it’s my favorite thing.

SHIFFMAN: Are you an optimist or a pessimist?

MECKSEPER: I’m sure most people would say I’m a pessimist. [laughs]

SHIFFMAN: [laughs] Probably.

MECKSEPER: …But I think of myself as an optimist.

JOSEPHINE MECKSEPER’S SELF-TITLED SOLO EXHIBITION IS ON DISPLAY AT ANDREA ROSEN GALLERY THROUGH JANUARY 18.