John Baldessari

For a very long time, John Baldessari had the distinction of being the tallest serious artist in the world (he is 6’7″). To paraphrase the writer A.J. Liebling, he was taller than anyone more serious, and more serious than anyone taller. As was inevitable, Baldessari’s hegemony in the height department has now been challenged by a handful of younger artists. What, is there to be no progress? Paul Pfeiffer, Richard Phillips, and certainly Mark Bradford have approached and possibly even surpassed Baldessari’s measure. But if it is true that these artists can see farther than their fellows, it is because they have stood on the shoulders of giants such as Baldessari (which, in Bradford’s case, would make him nearly 13 feet tall).

John has been a friend for more than 40 years. He was my mentor when I was a student at CalArts in the early ’70s, and it’s fair to say that meeting him redirected my trajectory as an artist—as it did for innumerable others. His legendary class in Post-Studio Art bestowed on those of us with enough brains to notice, a feeling of unbelievable luck of being in exactly the right place at the right time for the new freedoms in art—we arrived in time for the birthing, so to speak.

From a somewhat less than auspicious beginning, art history has turned out to be on John’s side. He initiated the use of pictures—photographs mainly, often with words in counterpoint—which has influenced generations. A life in art is full of contradictions: an art borne out of a desire to sidestep personal taste has become a universally recognized style—one that signifies a high level of taste. Collectors who, a few decades ago, might have considered “conceptual” art something they probably didn’t have time for are now lining up for a chance to own a Baldessari. Despite—or perhaps because of—John’s contrarian nature, he is firmly in the canon. His art is about many things—it’s intellectual and emotional, witty, acerbic even, at times also melancholic, poignant, and self-revealing. John has often used the form of the fable in his work, and his life has that same quality: a young man from Nowheresville, with no obvious prospects, bends the course of art to his vision. Along the way, he made levity and gravitas trade places.

This past June, I met up with John, now age 82, in New York just before the opening at the Marian Goodman Gallery of three large installation works. He was in the midst of finishing preparations for his first exhibition in Russia this fall, “1+1=1,” which is a selection of recent image-and-word paintings shown at the Garage Center for Contemporary Culture in Moscow. Sitting in a back room of the gallery, John and I had time for a little gossip before the floodgates opened and his public rushed in.

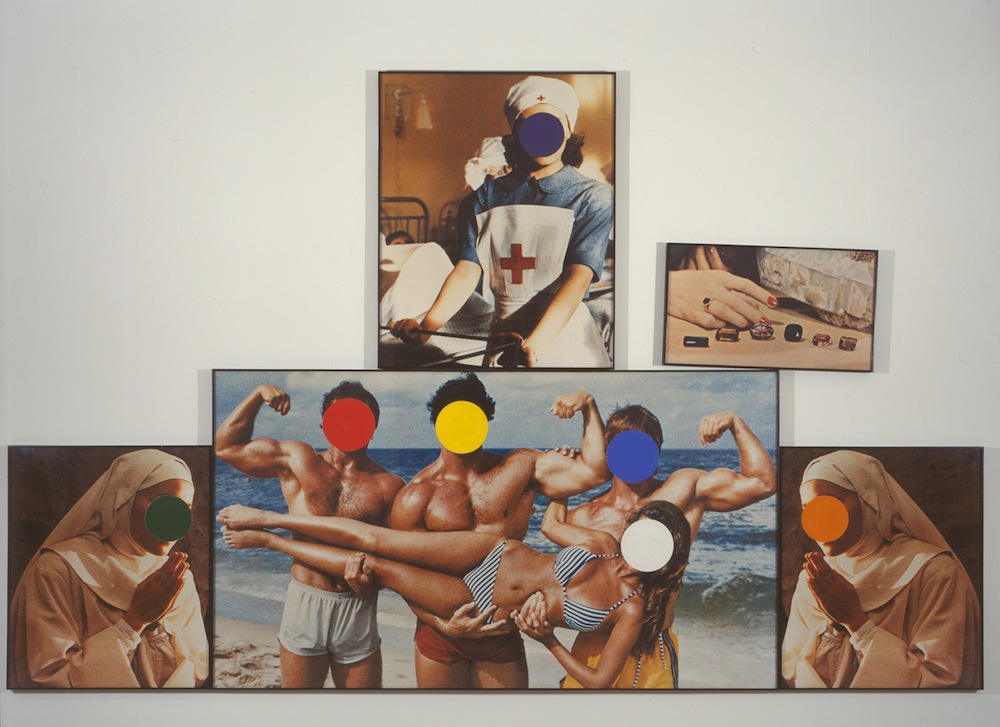

DAVID SALLE: I have a kind of sideline career as a Baldessari scholar by now. [laughs] Something to fall back on … Okay, I wanted to start with something you once said: A hundred years from now, you will probably be remembered as the guy who put dots on faces.

JOHN BALDESSARI: Yes.

SALLE: People tend to remember and mentally classify work according to how it looks, sometimes oblivious to the underlying intent. Does that ever bother you?

BALDESSARI: Yeah, it does. It’s human desire to be understood. And we always feel we’re not understood. When I read things about myself, it’s like I’m reading about this other artist—”Oh, this guy sounds interesting or not so interesting”—but I never think it’s about me. So there’s that. But, yeah, those works with dots in front of the faces—I did them for two or three years, and then it becomes a kind of branding, like Warhol or Lichtenstein.

SALLE: In the early ’70s, when I was in your class, and later, in the early ’80s, I found some of your work almost maddeningly but also tantalizingly obscure. It seemed as though obscurity was a positive virtue. I think I even used you as a license for my own tendency toward obscurity when I was younger. Now I find I just want to be as clear as possible.

BALDESSARI: I go back and forth between wanting to be abundantly simple and maddeningly complex. I always compare what I do to the work of a mystery writer—like, you don’t want to know the end of the book right away. What a good writer does is give you false clues. You go here, no, that’s not right; you go here, no, that’s not right, and then … I much prefer that kind of game. But then you get tired of yourself and you just want to be forthright.

SALLE: As André Gide said, “Don’t understand me too quickly.”

BALDESSARI: Yes, I remember that.

SALLE: And as Marilyn Monroe once told a journalist, “Don’t make me into a joke.”

BALDESSARI: I always remember this great response of an English professor. The freshman asked, how long should the term paper be? And he said, “Like a lady’s skirt, long enough to cover the subject, short enough to be interesting.” [laughs]

SALLE: Speaking of writing, if you were to compare yourself to a literary form, would you be a narrative writer or a lyric one?

BALDESSARI: How about narrative with a smidge of lyricism?

SALLE: Major in narrative, minor in lyricism. [laughs] Aside from yourself, who are some other artists whose work you find funny?

BALDESSARI: That word funny always makes me feel uncomfortable. Because if I were trying to be funny, I would be something like Bill Wegman—he really tries to be funny. I don’t try to be funny. It’s just that I feel the world is a little bit absurd and off-kilter and I’m sort of reporting.

SALLE: But I think that’s what great comedians do, great comic writers, great comic actors. They just read the headlines with the right eyebrow position and it’s funny.

BALDESSARI: That’s true.

SALLE: It seems your work makes use of the classic materials of the humorist: irony, inversion, mistaken identity, trading places, taking one thing for another thing, recombining malapropisms, solecisms, deliberate understatement—all those devices that are the foundation of humor also play a role in your work. It’s obviously a very sophisticated kind of humor. And not to in any way denigrate Wegman, but Bill goes more for the punch line. Of course, there other artists whose sensibility is fundamentally humorous, but few who actually make you laugh.

BALDESSARI: It’s also a little bit in the eyes of the beholder, I suppose. In one of my favorite New Yorker cartoons by Charles Addams, you see all the faces in a movie theater and all of them have this aghast look on their faces, and there’s this one face that’s laughing.

SALLE: It reminds me of the first time I saw Salò [1976], Pasolini’s last film, in the theater. It’s an absolutely horrifying film, but there was one guy in the audience who was laughing his head off. [laughs] Anyway, here’s a rather absurd question: How do you think your work might have been different if you hadn’t breathed and grown up with art history? I know that for me, art history is like a feather bed—you fall into it and it catches you. But I’m wondering what your work would be like if we didn’t have this image bank of thousands of years of art.

BALDESSARI: Would I even do art? I don’t know. I guess we get our idea about art from art history. I remember my first art classes in junior high school and high school, and so on. Where do you get the idea of a still life? Who had the first idea of a still life?

SALLE: I had a funny idea for a film. How come we never see student work in caveman art? All caveman art is perfect. Where are the rejects?

BALDESSARI: And why are there no still lives in cave paintings?

SALLE: Where was the Paleolithic art school? “No, that rock clearly doesn’t have the aesthetic qualities we’re looking for in a rock.” Also, how did they arrive at the perfect rendering of the bison? Where did they practice? They couldn’t have been great the first time out.

BALDESSARI: Where are the clumsy bison paintings? [laughs]

SALLE: I remember this girl once—she had these very romantic ideas about art. She asked me, “Where do you think your art comes from?” And I said, “Other art.” She got totally turned off.

BALDESSARI: Don’t use that line again.

SALLE: I’ll make note of that. In the recent lawsuit against Richard Prince, were you rooting for Richard in the copyright suit? [Prince was sued for copyright infringement by a photographer whose work he incorporated into a series of paintings and collages. An initial judgment found in the photographer’s favor, but an appeals court ruled in April that Prince had made fair use of the photographs.] Or do you think the photographer should have been given something, at least some acknowledgement as co-creator, if not some financial stake? Is it always finder’s keepers? How important is transformation?

BALDESSARI: In a very broad, general way, I side with Richard. I do think ultimately these ideas of copyright have to crumble. I think what Richard should have done was paid the guy first. A fair price—I mean, why not?

SALLE: I think he should have said, “My work wouldn’t have been possible without this guy’s work.” Some kind of gracious acknowledgment that this guy did the heavy lifting. What Richard did was to recontextualize it, to re-present the image—something the original photographer would not have thought of.

BALDESSARI: I think it’s copying when you don’t add anything to it.

SALLE: That’s a good definition. How do you think your work might have evolved differently if, for example, movie stills were very tightly controlled, and you couldn’t buy them at those places on Hollywood Boulevard?

BALDESSARI: I think they’re only tightly controlled if they only made good movies. There are always going to be bad movies, and there are more bad movies than good. [laughs]

SALLE: But say you had an idea for a crowd scene—a cast of thousands. Would you produce that kind of image instead of just finding a movie still of it?

BALDESSARI: No. I believe in the simplest way I can get to something, absolutely. I believe in simplicity.

SALLE: In the ’60s and early ’70s, when you, along with a few other people, were inventing conceptual art, what did you think you were doing? What did you think it’s future would be?

BALDESSARI: I think the term conceptual art came later. It’s a useful term for writers, a basket to put people in, like Pop Art or Impressionism or whatever. No, back then, I had abandoned painting because I thought there was something else out there. It wasn’t a notion unique to me. A lot of artists in the world were feeling the kind of malaise that Abstract Expressionism was running out of steam. I thought there was something else. I was always interested in language. I thought, why not? If a painting, by the normal definition of the term, is paint on canvas, why can’t it be painted words on canvas? And then I also had a parallel interest in photography. I would go to the library and read books on photography. I could never figure out why photography and art had separate histories. So I decided to explore both. It could be seen as a next step for me, getting away from painting. That might be fruitful. Later, that was called conceptual art.

SALLE: When you found that other people from different parts of the world had a similar feeling and spirit—of needing to invent an alternative to the existing forms—did you think, “Oh, this is a movement and I’m going to be a part of it. I can be its leader”?

A lot of artists were feeling the kind of malaise that Abstract Expressionism was running out of steam. I thought there was something else. I was always interested in language. I thought, why not?John Baldessari

BALDESSARI: Come on, I was in National City, California. [laughs] A movement? I thought I was going to teach high school, maybe have a family, and do art on the weekends.

SALLE: For my generation, the singular invention of putting together image with text—first in painting, then in photography on canvas, then later just as a photographic panel—was foundational, the great permission. Did you have the eureka moment of the inventor? Or was it just inevitable: “I like photography, I like language, now I’ll put them together.”

BALDESSARI: I thought National City was the end of the road. But then I realized that nobody was looking over my shoulder there. Nobody cared. I could do whatever I wanted. So I began to explore just for me what, in the Cartesian fashion, are the bedrock issues of art. I said, “Well, the way art is understood right now, it’s painting or sculpture. If we talk about painting, what constitutes a painting? Paint on canvas—that’s all it has to be. Those are the signals, and from that you can do anything.” I don’t think I would have ever done it if I had people looking over my shoulder, saying, “Oh no, you can’t do that. That’s not a painting.” But nobody cared in National City.

SALLE: When you made the first painting that was image and word, did you feel, “Now I’ve hit the mother lode. I’ve hit the thing that expresses my core”?

BALDESSARI: For myself, personally? Yes, I did. Because I wasn’t doing art to please others.

SALLE: Did you think of it as shifting art history one way or another?

BALDESSARI: No, no, no.

SALLE: What did you think when you saw other people, younger artists, taking it up and making something else out of it in their own way?

BALDESSARI: Good, because I think art, if it’s meaningful at all, is a conversation with other artists. You say something, they say something, you move back and forth. Yeah, I felt good.

SALLE: Do you think your art is masculine or feminine or gendered in any way? Let me tell you why I’m asking. I’ve been reading a lot about male writers in the ’50s, and it was a time when the masculine ideal was very much alive in the culture, certainly among writers, and I think equally, if not more so, among painters. There was a prevalent idea of masculinity in painting and writing, and then our culture changed, our idea of gender changed. As you were working at the time of this change, did you have any feelings about that as an artist?

BALDESSARI: I did. My mental image of the generic Abstract Expressionist painter is stripped down at the waist with a big brush in one hand and a bottle of Jack Daniel’s in the other. That period was male-dominated, okay. And then a paradigm shift comes with Jasper Johns and the image of a painter is different. Maybe it’s a guy in a tux holding a martini. And there’s a whole shift toward feminism. Most of my friends are women—that might say something. I think women are more interesting to talk to.

SALLE: Do you think Duchamp was a feminist?

BALDESSARI: I think so. Absolutely.

SALLE: I think so, too—as much as a Frenchman could be. He clearly preferred the company of women. Alex Katz once said that talent is the least of the things that matter in terms of a career. Do you agree?

BALDESSARI: I agree with Alex. Talent is cheap.

SALLE: Ideas are a dime a dozen, form is hard.

BALDESSARI: I think a lot of being good has to do with artists teaching each other. Like what we were doing at CalArts.

SALLE: When you started teaching at CalArts in 1970, did it feel like people were starting a new kind of art school out of the dissatisfaction with the old kind? Or was it just another teaching gig?

BALDESSARI: I really did think that CalArts was going to be the new Black Mountain College. I thought it was complete chaos at the time, but looking back, there was a great amount of order to it. Somehow something happened that was right. As you remember, I would get all kinds of artists out there with the idea that that’s how you learn about art: by having artists around. I remember you driving Daniel Buren around.

SALLE: I was also Germano Celant’s driver—among others. As students, we met absolutely everyone, from those who had just one eyeball above the dirt, basically, to some of the great masters.

BALDESSARI: I remember when one prominent artist came out and I had an argument with him because I considered the people I work with not as students but as young artists. He said, “Not students?” I said, “Listen, when they’re our age, they might be a lot better artists than we are.” They’re artists. Keeping that wall as low as possible between instructor and student was really helpful, because I think we all believed something could happen.

SALLE: I know that artist you’re referring to believes CalArts empowered all of these people a little prematurely.

BALDESSARI: I was learning as much from you and Matt [Mullican] and Jim [Welling] as you were learning from me. It was a great exchange.

SALLE: I have never known anyone with more ideas than you. You always seemed to have a steady stream of ideas. Have you ever felt blocked? Have you ever temporarily run out of ideas?

BALDESSARI: I think that’s the panic we all have, isn’t it? And I’m particularly vulnerable because I get bored so easily. I’m not a one-idea artist. I have to keep on pushing. I tell myself, “Well, it’s time to turn on the popcorn machine.”

SALLE: I guess ideas come out of dissatisfaction with what exists—that which you already know.

BALDESSARI: Your art comes out of your art, too. If you’re smart, you abandon the things that didn’t work out so well, and you enlarge upon the things that seem to be successful. A lot of ideas don’t translate very well into art. To say, “Oh my god, the grass is green …” You’re going to end up with a big green painting. [laughs]

SALLE: That raises a question I have about intentionality. In the culture, we talk about shifts in sensibility, shifts in taste, the idea that what mattered was intention rather than result …

BALDESSARI: That’s a question we routinely brought up in the grad seminars we had. What were you trying to do?

SALLE: And how could you have done it better? When I teach, I will often tell a student, “I don’t care what you’re trying to do.”

BALDESSARI: I remember one student was showing a film in this really brown, brackish light, and I said, “What were you trying to do with that?” He said, “One of the bulbs burned out.” [both laugh] But one thing I tried to do was to get everyone to be very articulate about what they were doing and not to say, “Oh, well, I just sort of did it.” I also used to jokingly say, “I don’t teach art. I’m an art doctor.” Students come to me and say, “My art’s sick,” and we help them make it well.

SALLE: I hadn’t heard you say that before. That’s how I think of teaching, too. The engine’s not running so hot—we bring it into the shop and do the diagnostics. Your bio says you’ve had more than 200 one-man shows. Do you think that’s a record?

BALDESSARI: All that says to me is I should get a life. [laughs]

SALLE: Leo [Castelli] used to say, “Some artists like to say no and some artists like to say yes.” You’re obviously an artist who likes to say yes. People ask you to do a show, you say, “Let me see if I can fit it in my schedule.”

BALDESSARI: I think I’m incredibly lazy. God, I’m just sitting on my ass.

SALLE: You make things that can sometimes look very simple, almost like anyone could do them. I assume this is a result of much hard work on your part to get to that point—a very honed, refined physical skill. Has there been a body of work in your memory that stands out as being particularly hard, either to get started on or to complete? For example, when you did I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art [1971], did that start out as something else, or was it a complete idea from the beginning?

BALDESSARI: My model as an artist has always been Matisse, who made things look like anybody can do them. But he himself has said, “A painting’s not done until it’s been back on the anvil 20 times.” Trying to make it look simple, that’s been my goal. And vis-à-vis your question, that particular piece came out of a note to myself, and it was really talking about some of the conceptual art I was seeing. It was just academic. I’d say, “Okay, I’ve been in the university. I can speak like that.” The first iteration was at Nova Scotia College of Art & Design. They asked me to do a show, but of course, they had no money. So I said, “Okay, tell students they can come in the gallery and write ‘I will not make any more boring art’ on the wall as art punishment.” I thought it would be a blank gallery, but the gallery was filled. I said, “Wow, a lot of artists might be feeling badly about this.”

SALLE: Everyone was doing their penance. But then a bigger project came out of that sentence.

BALDESSARI: One sentence, exactly. I made a video out of it.

SALLE: What about your video, I Am Making Art [1971]. That’s one of your most iconic. When I saw it again at the Met, I laughed out loud—just as I had the first time I saw it.

BALDESSARI: Again, that came out of my own thinking—like, what is basic in art making?

SALLE: The idea was brilliant, but so is the execution. Did it go through different iterations? Sometimes you read famous comedians talk about the evolution of the joke. To know how to structure the joke perfectly so that the narrative information is given in the right tempo, in just the right dose—it sometimes takes quite a lot of work. It seems easy when you hear the joke. That marriage of subversive intent, factual information, and visualization in I Am Making Art was so perfectly compressed, you couldn’t tease them apart.

BALDESSARI: I remember so vividly that all video tapes were 30 minutes long, and I thought, Shit, I have to remember all of the positions that my body is in while I say, ‘I am making art,’ so I don’t repeat myself.

SALLE: Your work was first embraced in a big way by Europeans. Do you think your sensibility is particularly European or American or neither or both?

BALDESSARI: I remember trying to shop my paintings around L.A. and not having any success, and somebody said, “Well, your work is more European.” I had no idea what that meant.

SALLE: What does that mean?

BALDESSARI: I still don’t know what it means and I don’t know what the reason is. But I’m a first generation American. I have European parents. I was probably raised European without even realizing it. That could be it. But I had more influence in Europe. Those galleries, like Konrad Fischer in Düsseldorf, were picking up all the artists that the U.S. didn’t care about.

SALLE: What do you think Konrad saw in your work?

BALDESSARI: I think with Konrad, having been an artist himself, it was a matter of whether he’d believe in you. Did you talk like an artist? Did you feel like an artist? Then he’d just give you blanket approval. That was it.

SALLE: So it was instinct about you as a person. That makes sense. The writer James Salter said that one of the nice things about life was that you got to rearrange the pantheon-raise up or demote certain individuals. Is there any artist you would move down to the basement for a while?

BALDESSARI: God, I can’t say that. [Salle laughs] Yeah, there are a lot—and a lot to move up. I always thought that Richard Artschwager wasn’t high up enough.

SALLE: Not sufficiently esteemed. I would agree. Some people’s turn at the top never comes.

BALDESSARI: I’m so interested in what accounts for shifts in taste and why some things are suddenly celebrated and some things not. Pendulum swings always interest me. Now I’m sure because of the Venice Biennale, every gallery is going to have one outsider artist just to be on the safe side. You better cover your ass.

SALLE: Do you think there is a better or best version of life, and if so, does art have anything to do with that? Does art illuminate the good life for people in any way?

BALDESSARI: I think I live such a boring life. But I can’t imagine any other kind of life, so I guess it’s the life I want. I can’t imagine a life without thinking, doing art. I don’t feel any need to be a world traveler or an adventurer. I don’t have any bucket lists. I’m very happy doing what I’m doing. I think somehow I know that I should have a larger vision of art, but I can’t think of what that would be.

SALLE: Once established, a successful style looks like an inevitability—maybe that’s the definition of a successful style—but there’s often the time when it looks like anything but. Alex Katz once said vis-à-vis his being a realist painter in the ’50s—the heyday of abstraction—that he felt like he’d dug a giant hole for himself and jumped in. In the ’70s, when you were developing your style, did you ever think you were in the wilderness?

BALDESSARI: No, I don’t think so. Actually, I always felt like I was right out of Dickens, looking in the window of the Christmas feast, but not at the feast. I still kind of feel like that, but I’m going to do what I do, so it doesn’t really matter. I always have felt that I have been sort of out of step … Marching to the beat of a different drummer sounds too romantic.

SALLE: You’ve been showing for a very long time in every conceivable context in the art world—on the page, on the gallery wall, in the movie theater. There’s definitely times when it must have felt lonely. But it doesn’t seem as though it ever kept you from doing it and doing more of it.

BALDESSARI: I still have that vestigial idea that all these other people are artists. I’m an artist wannabe.

SALLE: I guess that’s what’s kept you pure.

BALDESSARI: Well, maybe we never get rid of that.

SALLE: Do you think Richard Serra has his version of that feeling?

BALDESSARI: I have no idea. Although I remember a quote of his, when he first came into New York and was looking around at people doing sculpture. He said, “I can do this.” I don’t think I ever had that kind of self-assurance, but I admire it.

SALLE: Many artists have tried to embody a Borgesian sensibility—the “Library of Babel”—the roundabout, circuitous journey, that type of trope. It seems to me that your work does that better than most. You remind me of the Borges character who travels aimlessly around the globe without knowing why or without having any method or goal, only to discover at the end of his life that the map of his travels describes the outline of his face. Does that ring a bell?

BALDESSARI: Yeah. [laughs] That’s true. I’ve always had this method of working: I think of following an idea to its logical trail—where would it take me—and instead of stopping there, I think, “What if I just kept pushing it a little bit further? Where would it go?”

SALLE: That seems to be one of the operating principles of your work. You can’t account for how it got from this point to that point.

BALDESSARI: One of the games I play at night when I’m trying to go to sleep is that I start with a part of a word like E-A-S-T. Then I go through the alphabet. I start with A, okay, that doesn’t work. B, okay, beast. I go to the end of the alphabet. You never realize so many words have E-A-S-T in them until you play that game.

SALLE: I’ve been playing word games with an 8-year-old girl. It’s amazing what you can learn from a child.

BALDESSARI: I learned so much about art from watching a kid draw. I taught at the grade-school level. Kids don’t call it art when they’re throwing things around, drawing—they’re just doing stuff. I think it’s the first year of junior high school it ends, because the girls start drawing horses and the guys start doing fighter planes and tanks and that sort of thing.

SALLE: That marriage of word and image that we spoke of earlier—that simple binary operation of putting two things together and letting them stand, which I associate with your work from the early ’70s—seems to be playing a bigger role in the work in the last four or five years.

BALDESSARI: For these fairly recent pieces, you’ve got high-end restaurant entrées and press clippings. People are thinking why, but in my mind, the more events escalate, the more we think about food.

SALLE: There’s something very satisfying about the look of a flashcard—it speaks to the need for clarity. The aesthetic of the flashcard kind of sums up what was in the air during that time at CalArts as well. It was foundational.

BALDESSARI: That should be the goal for all art, to be as simple as a flashcard. There’s that early videotape where I’m trying to teach a plant the alphabet with flashcards [Teaching a Plant the Alphabet, 1972].

SALLE: That’s a crystalline presentation of it. Teaching a plant the alphabet takes on an almost Beckett-like, vaudevillian slapstick quality. Teaching a plant is so dumbly pedagogical—the sincerity of it.

BALDESSARI: Again, I’m just picking up on something in the culture. Back then, if you remember, there were people who thought one could communicate with plants.

SALLE: But do you agree with me on the Beckett-like, vaudeville-clown pathos on that work?

BALDESSARI: I think the idea of vaudeville clowns and court jesters is always to show the flaw, to point out what’s not working and why it’s not coherent. So I share a lot of that. I do think a lot of dumb humor is incredibly profound at the same time. An antisophistication can be kind of refreshing, I think.

DAVID SALLE IS A BROOKLYN-BASED ARTIST. HIS FORTHCOMING SHOW, “GHOST PAINTINGS,” OPENS AT NEW YORK’S SKARSTEDT GALLERY IN NOVEMBER.