INTERIOR LIFE

Jay Johnson Remembers the Quiet Luxury and Kindness of His Brother Jed

In a shady enclave at Interview HQ, there’s an Amish-style settee situated against a wall outside of the kitchen. Its upholstery weaves a navy and white floral pattern that’s scratchy to the touch and has chunky oak legs holding up a seat that’s beginning to concave from age. The sofa’s rigid back isn’t particularly comfortable and, to many of my colleagues, the period piece feels out of place within our contemporary Chinatown office–an anachronism that looks more like a relic in the presence of a framed portrait of Kim Kardashian’s bare butt. To me, the loveseat exudes a certain charm and folklore, partly because it once belonged to Ingrid Sischy, the legendary editor who ran the magazine from 1989 to 2008, but primarily because it was designed by Jed Johnson.

Last month, Rizzoli released a celebratory re-edition of Opulent Restraint, a 224-page monograph that documents Johnson’s illustrious career. First published in 2005, nearly a decade after the designer’s tragic death in a TWA Flight crash in 1996, the reissue comes shortly after the premiere of last year’s The Andy Warhol Diaries, which likely acquainted many Netflix streamers for the first time with Johnson, the janitor-turned-film director-turned decorator who found himself in a complicated romantic and professional relationship with Warhol. While Johnson’s achilles heel will always be seen as his companionship with Interview’s founder, the pages of Opulent Restraint illustrate a passion and creativity that far eclipses the pop artist’s shadow.

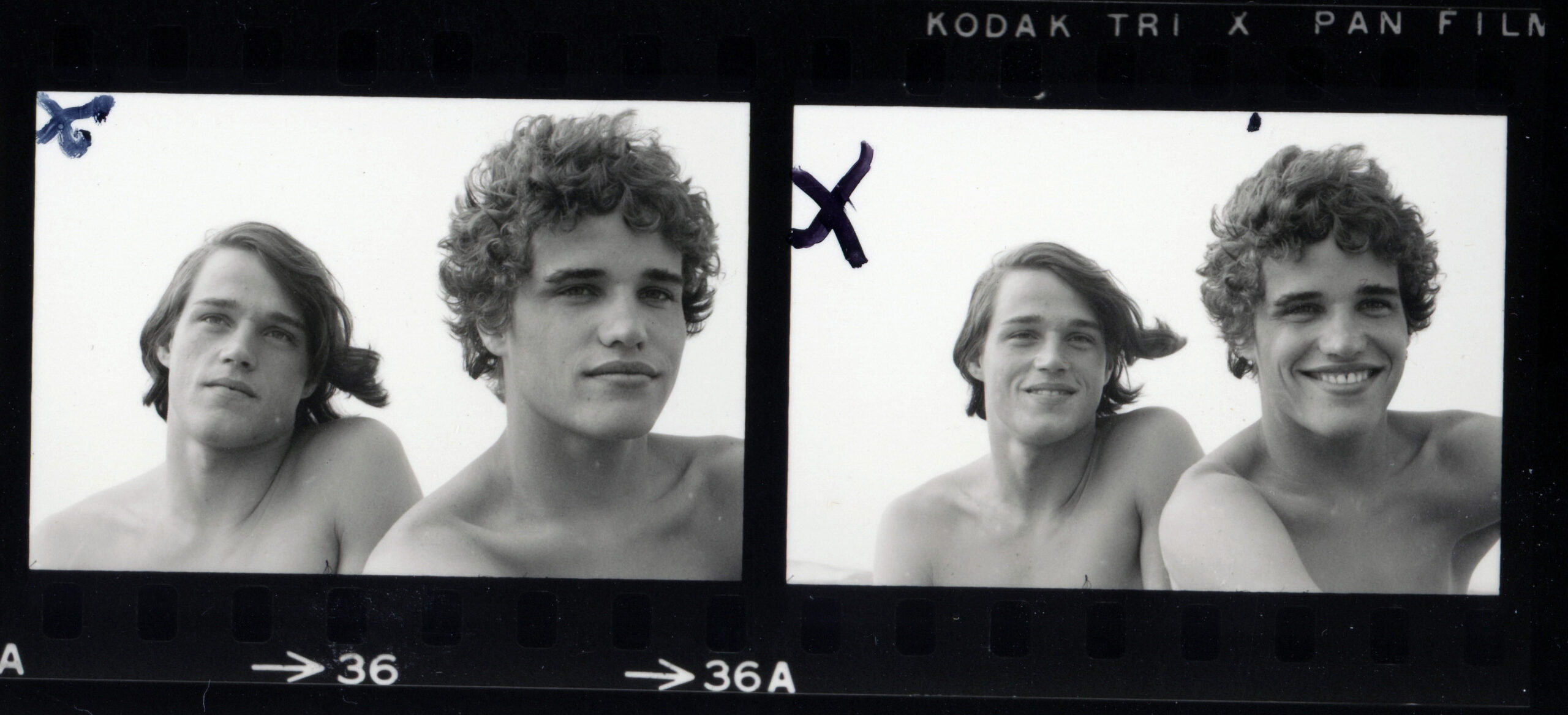

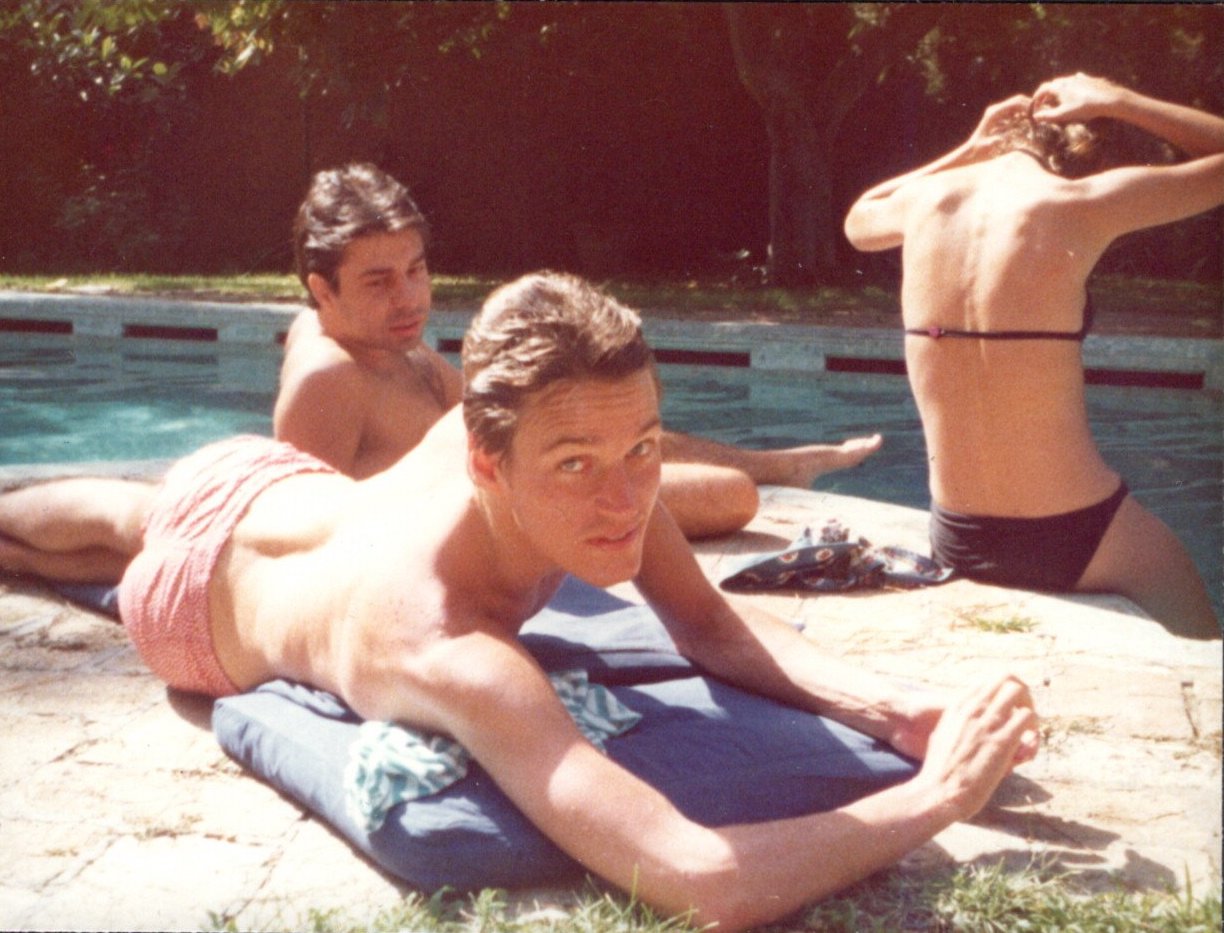

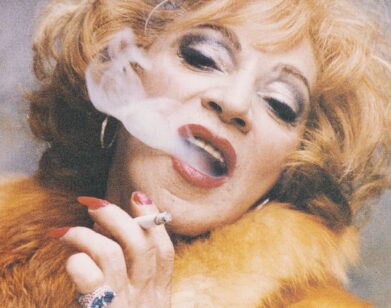

Flipping through the book, Johnson’s comforting architectural spaces go down like a sip of warm brandy, exuding a fancy flair while still making you feel like you could cozy up with a blanket and an Agatha Christie novel. It’s a look that most Internet dwellers today would call “quiet luxury,” an aesthetic that obsesses TikTok users for whom a cable knit sweater, tied around their neck, or a signet ring imbues a rarified, understated elegance. But what Johnson conceived in his professional lifetime truly epitomizes the term. To learn more about the man behind the decorator, I logged onto a Zoom call with Jay Johnson, Jed’s fraternal twin brother and the person who knew him best.

Below, Johnson’s conversation accompanies interior shots from Opulent Restraint, along with exclusive imagery provided by our friends Paul and Devon Caranicas, arbiters of The Antonio Archives, the artistic enterprise that preserves the legacy of artists Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos.

———

MITCHELL NUGENT: You grew up in many different states—Minnesota, Arizona, California. Did you and Jed have a favorite home as kids?

JAY JOHNSON: No, we grew up in a big and very poor family. That’s why we lived in a lot of different houses. We left Minnesota when we were 10 and moved to Arizona because my father thought he could find work there [but] that didn’t work out too well. We were only in Arizona for about eight months and then we went to Sacramento and left when we were 18. New York has been home since I was 18.

NUGENT: What were your childhood bedrooms like? Crowded?

JOHNSON: Very [laughs]. Yeah. I guess you don’t really notice so much when you’re young.

NUGENT: I read in your foreword about how you and Jed loved to make forts as kids. Growing up in so many different houses that were bristling with kids, was that one of the first moments when you were able to create a space of your own?

JOHNSON: Yeah, I think it was a lot of fun for us to go and have our own little spot somewhere. In Minnesota, when we were young, we spent a lot of time outside unsupervised. We would go into the woods and build things.

NUGENT: What was it like coming to the city in 1967 and immediately falling into the Factory orbit?

JOHNSON: Coming to New York was pretty much an accident because it isn’t what we had planned. We were just miserable in Sacramento and we thought, “Oh, we’ll take a break from college, maybe a semester, and travel somewhere.” Jed had been to Montreal for the World’s Fair the year before and so we thought, “Well, let’s go there.” He had a really good time and we got as far as Buffalo and [conductors] kicked us off the train because they thought we were draft dodgers and vagrants. So, we got on a bus in Buffalo and came to New York without planning and just went to the East Village, which we knew looked like San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury, and thought we’d find like-minded hippies and a place to stay. And that’s what we did and we found an apartment on 10th Street.

NUGENT: Very serendipitous. What was that first apartment like?

JOHNSON: We weren’t there very long but it was really exciting to have your first apartment. We had no idea about New York and it was in a very bad neighborhood full of junkies. It was a walk up on the fourth floor with broken windows and there was nothing wrong, [but] we got mugged immediately.

NUGENT: Oh, no!

JOHNSON: The story is that we had to go to Western Union and ask my mother to send us some money, and she sent us a hundred dollars or something. And the guy at the Western Union office felt sorry for us and said, “You need a job delivering telegrams.” And we said yes. It was a very cold and not a very interesting job. So one day, Jed happened to deliver a telegram to the new Factory and [film director] Paul Morrissey said, “Would you rather work inside than outside? We just moved here and we need somebody to help paint and clean.” So that’s how we started.

NUGENT: Wow, a lot of happenstance. Being kicked off the train and then you both end up delivering telegrams and end up at the Factory. It’s incredible how the world works sometimes.

JOHNSON: Yeah, it was all just rolling into place. And then Andy had a charge account at Max’s Kansas City because he had traded a painting for food.

NUGENT: What a lucky deal for Max’s owner [laughs].

The Andy Warhol painting “Merce” surmounts a galuchat blanc cabinet by André Groult in the former estate of Sandra & Peter Brant, Greenwich, CT, 1982

JOHNSON: So Andy said, “You’re welcome to go and use my credit to eat.” So that’s where we’d go to have dinner every night. And one evening, Andy gave us a ride home and he said, “This isn’t such a good neighborhood for you to be living in. You should just find some other place.” And so we found another place that he loaned us some money for getting a deposit for this place on 17th Street.

NUGENT: Very generous of him.

JOHNSON: Then, shortly after we moved to 17th Street, Andy was shot. Then Jed got more involved in helping with Andy healing [at the hospital] and he would bring him the gossip from The Factory every day in the mail and visit him. And so when he was ready to be released to go home, Andy asked if [Jed] would come back to the house and help. And from there, some relationship developed between them.

NUGENT: Many of the essays in the book describe Jed’s move from 17th Street and to the first as the moment he began to find his calling in design. And an instant when he realized Warhol was addicted to shopping.

JOHNSON: Jed quickly realized It was like a hoarder’s place. Andy’s mother was living there still down in the basement. And so he started organizing all of Andy’s collections of the stuff that he had, the cookie jars and all of that. I think that Andy was happy with the order and his mother was happy with it. But I don’t think that it was his connection to design at that point. I think he was still interested in helping Paul Morrissey with the films at The Factory and that was what he was concentrating on doing a lot of editing. He had just moved up from the janitor to being Paul’s assistant and staying at Andy’s.

NUGENT: So when do you think Jed started to think about design as business?

JOHNSON: He always had a passion for architecture. When he started college, he was taking architecture classes and designing rooms. But I think when Andy said, “Jed, why don’t you go find us a new townhouse?” Andy’s mother had left at that point and I think Andy wanted to move out and find a bigger place. And so Jed had looked for a house and he found the one on East 66th Street.

NUGENT: Ah, so it was at the new townhouse.

JOHNSON: Yes, that’s when Jed started decorating and working on that house and putting together all the rooms. That’s when I think he decided. He had a bad experience with the films. He had directed Bad and it wasn’t a financial success and I think he got blamed for it in some way by Andy. And so Jed said, “I’m not going to do this anymore.” And so he started concentrating on the townhouse.

NUGENT: I believe Bob Colacello said the decoration was akin to The White House.

JOHNSON: His idea was to bring it back to a real authentic period. It almost became museum-like. He had the best English furniture. He had the curtain maker from the Metropolitan [Museum] do all the drapery. [It took] about three years and a lot of research. So I think he then got really involved and thought, “This is what I really like doing.”

JOHNSON: Have you seen the new book?

NUGENT: Yes, I have the re-edition and a first edition from 2005.

JOHNSON: I changed the cover [for the second edition] because the original one was all the Arts and Crafts style, and I wanted to put Andy’s townhouse on the new one to show a diversity of Jed’s style, Andy’s passion for collecting, and wanted people to really know that Jed was the main person as involved in creating that space.

NUGENT: As you should. It’s such a magical space.

JOHNSON: It really was and not many people got to see it. I know Jed was very proud to show it when he could. Andy was always very paranoid about having people in the house and worried about fires and bad things.

NUGENT: I gather you got to visit?

JOHNSON: Well, I was there almost every day because when he started his business, the office was in the upstairs bedroom. I would go every morning and start work.

NUGENT: That was an easy commute for Jed! You mentioned in your foreword that when Pierre Bergé saw Warhol’s townhouse, he enlisted Jed to design his apartment at the Pierre, which was a major catalyst in him starting his own firm. Do you remember how he felt in that moment being able to put his name behind a business and really make design a new venture?

JOHNSON: I think he was very nervous and he started working with a lady named Judith Hollander, who was a collector of American furniture. Pierré had said he wanted the apartment to be completely American in style. But every time [Jed] would go to an antique dealer and find the perfect piece of furniture, they’d say Judith Hollander already bought it. So then he started buying it back from her and then they became friends and started working together. And then she decided she hated doing that, so he started his own company called Jed Johnson Associates [laughs].

NUGENT: And you were his first employee. What was it like working with your brother?

JOHNSON: I did everything. It was fun. It was doing the accounting, the invoicing, I didn’t get to do any of the designing or put in my two cents.

NUGENT: Did Jed ever ask for your two cents?

JOHNSON: Not really. I think he thought I was, I don’t know, too suburban, maybe [laughs].

NUGENT: What was your working relationship like? Did you butt heads?

JOHNSON: No, not really. He would get mad a few times. I’m not so great at taking notes and so it was like, “Did you remember to do that?” And I would say, “Sorry. I forgot to do that.” But in general, Jed was my best friend and we had a fantastic relationship. We enjoyed being together and it was very cordial. I didn’t know what I wanted to do, so working for him was not an idea that I had. So it was more [Jed] offering me an opportunity.

NUGENT: That’s very special.

JOHNSON: I had been working for a fashion designer. I had a number of different jobs previously. I worked for the Iolas Gallery for about a year and I worked in a few nightclubs. Andy had got me a job at Arthur’s [nightclub]. So this was nice to have a steady job working with my brother and being able to go to the townhouse every morning.

NUGENT: And to have your brother cut you a paycheck every week!

JOHNSON: Exactly [laughs].

NUGENT: Can you recall any outrageous requests from clients or fun memories of design projects?

JOHNSON: There was a point when Jed kept getting calls from Barbara Streisand. Somehow he got pigeonholed into the idea that he did Arts and Crafts style, and she was in this period of doing that style house in California. So she kept calling him because she thought he was the professional, but he didn’t want to work for her because he thought it might be really difficult. She wanted just one bedroom to be done, and so he finally said yes but then she ended up buying her own things. And at one point, she bought a four-poster bed in London from John Stefanidis, I think. And when it came, the bed didn’t fit and Jed got blamed for it not fitting. And that was very funny working out who’s going to pay for the bed [laughs].

NUGENT: Barbara has to! Do you remember if there was any particular project that Jed was incredibly proud to realize?

JOHNSON: The Marshall Cogans. I think he was really proud of that one. I think at that point he had really developed a lot of confidence about his idea of how people lived. With Andy’s townhouse, it was very stilted, too museum-like and unapproachable. That’s where the “opulent restraint” came from, the design being really special, having the most incredible art and furniture but designed in such a way that it wasn’t overwhelming.

NUGENT: I know that he and Andy’s shared puppies, Archie and Amos, were really dear to Jed. Did he ever create anything special in his homes for the dogs?

JOHNSON: No, he didn’t. They were mostly always in his arms, always carrying them around. He was always worried about them walking up and down the stairs. And the townhouse did have an elevator, so the dogs always had to take the elevator. He wouldn’t let them walk down the stairs then.

NUGENT: Too funny. Jed designed the Interview offices. Do you remember what that project was like?

JOHNSON: I remember the project but I wasn’t involved. So basically, I just really saw it finished and I always worked in the accounting department, so I remember making sure it was kept within budget.

NUGENT: What’s it like for Jed’s legacy to live on in cultural moments like The Andy Warhol Diaries and the re-edition of Opulent Restraint?

JOHNSON: I’m really happy that through the Diaries, young people became interested in Jed, and [Rizzoli] decided to reprint the book because they had enough people asking for it. I’m happy that they get to see the relationship and what Andy and Jed’s relationship was like. That was important. I was nervous. Sometimes those things don’t turn out so well and I wanted to be able to make sure that the truth was told. And I think that they did a good job.

NUGENT: From my perspective, Jed was the unsung hero of the entire series. My friends and I talk about Jed and we’re all so enamored with this sensitive soul, and this person that just seemed to care about everything and everyone and was really gentle, from what I could gather.

JOHNSON: He was always very, very generous. He was always very generous with his family and cared deeply about his friends and his friendships.

NUGENT: Ingrid Sischy said Jed was “deep, modest, sensitive and wry.” What do you make of that assessment? How would you describe his personality?

JOHNSON: He was very introverted and very quiet but forceful in his opinions for clients and somehow he would be able to get it across, whether something was right or wrong, he could win them over somehow. He educated them, really, and he was such a kind person. People and clients really trusted him. They knew they weren’t going to be mistreated. He was very, very trustworthy.

NUGENT: Warhol said Jed made homes wherever he went.

JOHNSON: Yeah, and a lot of good friends. He was lucky.