The Revolution Continues

A disclaimer painted on the floor just outside of the International Center of Photography reads, “By entering this area, you consent to being photographed, filmed and/or otherwise recorded, and surrender the right to the use of such material throughout the universe in perpetuity.” Though this warning is a permanent fixture of the museum, its disconcerting tone is echoed in the exhibition to which it currently leads: “Perpetual Revolution: The Image and Social Change.”

“Perpetual Revolution” takes aim at its two stated subjects, and explores how visual culture has kindled social change in six areas: climate change, racial discrimination, the refugee crisis, gender fluidity, terrorist propaganda, and the right-wing fringe. The works on display include photographic prints and digital media—smartphone videos, Instagram feeds, Twitter accounts, and memes—spanning multiple decades.

“I want people to understand that the web is not really just a stream of endless images,” says Carol Squiers, who led the show’s group of curators. “It’s a series of individual images and you still have to look at each the way you did in the past.” The exhibition is replete with chances to do just that, placing images of the past alongside feeds of the present. Take its section titled “Climate Changes,” which among clips of collapsing glaciers and surging sea levels, includes “Earthrise,” NASA’s iconic photograph of Earth shot from space in 1968, as well as the Instagram feed of Camille Seaman, a photographer who camped at Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in 2016. Shot almost half a century apart, the former became an emblem for the environmental movement, credited with inspiring the founding of the Environmental Protection Agency, and the latter joined a torrent of images on social media that funneled public attention towards the Dakota Access Pipeline.

“Social media is the great political action tool of our time,” Squiers notes. The efficacy of social channels in promoting change and activism is at the crux of the exhibition, which features the ways in which it has both succeeded in raising consciousness and failed. The exhibition’s section on race, “Black Lives (Have Always) Mattered,” speaks to how the Black Lives Matter movement woke much of the nation from a deluded reverie by calling attention to the institutional racism that, too, has always existed (and mattered). “#BlackLivesMatter has done amazing work—I mean, talk about a hashtag. It’s not all #KimKardashian anymore,” Squiers says. (“Although Kim is trying to do her part these days,” she adds).

But it can also be said that the trending nature of hashtags leaves little room for longevity, as exemplified by the works in “The Flood: Refugees and Representation”—specifically, Turkish artist Hakan Topal’s limestone powder reconstruction of the Syrian-Turkish border upon which videos and images are projected. Among them is that of Alan Kurdi, the Syrian child whose body was photographed on the shore of Bodrum, Turkey and appeared on millions of screens within hours. Although the overwhelming response did raise much-needed awareness, it also exposed some of social media’s shortcomings: Images that reach almost-instant virality are often fleeting, and context risks getting swallowed by hasty shares and deployment of sad-faced emojis. The reaction brings to mind the recent siege of Aleppo, and the world’s quiet impassivity in watching—at times in real time—an unconscionable attack on a civilian population. “Just because things are so sped up and there are so many more images and everything goes past us so quickly doesn’t mean that you should pay less attention,” says Squiers. “Now you have to pay more attention.”

A group that has long resided in the periphery of public attention is the transgender and gender-nonconforming community, and as Squiers says, “Genderqueer people have been using various platforms on the web since before there was Facebook or any of that stuff—when it was still message boards.” “The Fluidity In Gender” weaves a narrative of self-invention for those who exist beyond the gender binary and so must create spaces in an often hostile, heteronormative, cisgender landscape. It is both uplifting (“The fact that so many people have been connected and [are] able to use social media to work out very complex notions of personal identity I think is extraordinary,” observes Squiers) and a somber reminder of enduring erasure and exclusion.

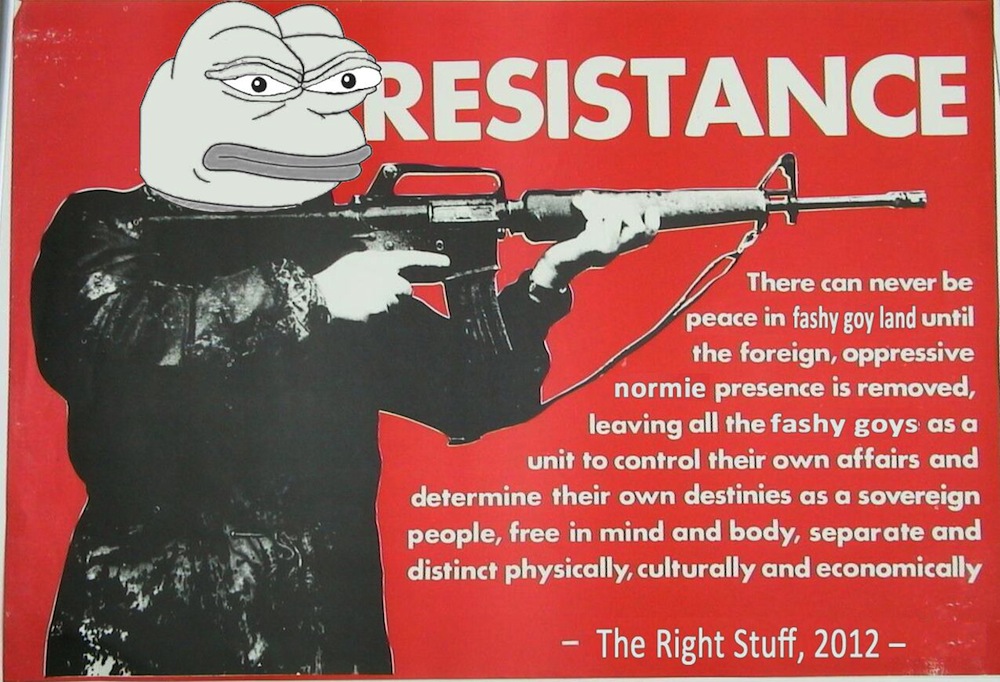

“Propaganda and the Islamic State” explores a group that, although vehemently different in every other aspect, likewise solidified via the Internet. ISIS’s rhetoric, rooted in visions of utopia achievable through sacrifice and obedience, employs social media as a conduit in disseminating terrorist propaganda through an array of mediums from images, podcasts, and videos to songs and magazines. It emphasizes the material changes and effects that visual culture can have when it traverses into the real world from the virtual. Such palpable changes are particularly poignant in “The Right-Wing Fringe and the 2016 Election,” perhaps because of its timeliness. Reddit threads, Tweets, and an assortment of memes—Hillary Clinton, Ted Cruz, Pepe, the President—flicker across screens, propagating white nationalism under the more palatable veneer of “alt-right.” “The word ‘responsibility’ and social media hardly belong in the same sentence,” says Squiers. “So many people feel no responsibility to the truth. Any lie can be produced by anyone and there’s a certain percentage of people who’ll believe it. If people in positions of power are just outright provably lying to you, the idea of anybody having a responsibility for anything is kind of ridiculous.”

Oxford Dictionaries declared post-truth—”circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief”—2016’s word of the year, but its hold remains strong in 2017. “Although all around you can see people not interested in either truth or objectivity, in your own practice, you have to stand up for both,” says Squiers. In times of alternative facts and misinformation, images can shape, not only reflect, social change, for better or for worse. While the extent of the changes is oftentimes unpredictable, they have the potential to be truly great—in all senses of the word.

“PERPETUAL REVOLUTION: THE IMAGE AND SOCIAL CHANGE” IS ON VIEW AT THE INTERNATIONAL CENTER OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN NEW YORK THROUGH MAY 7, 2017.