STUDIO VISIT

“I Want Bad Reviews”: Mathieu Malouf, in Conversation with Rita Ackermann

Photo courtesy of the artist and Nahmad Contemporary, New York.

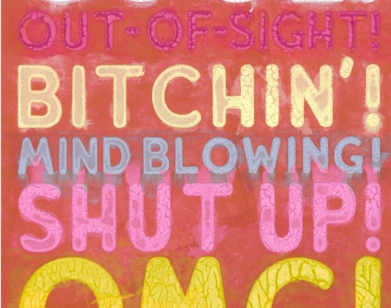

Mathieu Malouf wants a bad review. Following a few polarizing solo shows, the French-Canadian artist earned himself a reputation as an antagonist and crusader against political correctness. But what he really wants is to be challenged for his ideas, not his personality. “A bad review totally fixes the problem of having to forgive yourself, because somebody else took the offense,” he said on a recent call with fellow artist Rita Ackermann, who’s similarly bored with critical acclaim. Malouf’s most recent show, Women and Penguins, on view at Nahmad Contemporary until March 20th, strikes a more sincere tone and features large paintings of exactly what its title suggests: women and penguins, the latter of which came to the artist’s mind after he ingested a weed gummy. On a Zoom shortly after his show’s opening, Malouf talked to Ackermann about procrastination, Picabia, and what he learned from Jeff Koons’ MasterClass.

———

RITA ACKERMANN: Hey, Mathieu.

MATHIEU MALOUF: Hey.

ACKERMANN: Are you upstate?

MALOUF: Yeah. I was trying to start a fire in my studio just to have something to do. I’m probably going to get cancer from this interview because I have this fireside chat thing going on. Are you in your studio?

ACKERMANN: I am. I’ve been spending a lot of time with your work today. I got my coffee and started looking at your art.

MALOUF: Oh, god. I’m sorry.

ACKERMANN: I have to say, I’m having a really good time. Very impressive so far, all of it.

MALOUF: There’s a lot of them.

ACKERMANN: I also very much like your last show. It’s rare to see paintings with a great sense of humor and to be able to tell that the person who made them enjoyed making them without cruelty. I mean, correct me if I’m wrong. It did not look like somebody suffered making those paintings. They are full of grace and joy.

MALOUF: Oh, really? That’s cool. I don’t know if you suffer when you make art, but I work fast. Not fast, but intensively. I’m not able to just pop into the studio and then do other things. Maybe that’s why I have a studio in the woods now. Right now I’m staring at 10 unfinished paintings and I have to finish something for tonight. There’s a FedEx pickup tomorrow for this show in Basel, and it’s really a lot of suffering to look at unfinished work.

Mathieu Malouf: Women and Penguins Installation Image. Courtesy the artist and Nahmad Contemporary, New York. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

ACKERMANN: Do you overpaint to have work to choose from?

MALOUF: Yeah. There’s one that’s almost not horrible, but I’m always wondering why I work so last-minute. It’s like I can’t finish anything without a gun to my head, it seems.

ACKERMANN: So maybe they’re not that fun to make.

MALOUF: It’s very fun to finish them, but the process…. I don’t see therapists, but this would be a valid reason, trying to sort out why I have to torture myself so much before it gets fun. You’re not like that, right? You don’t suffer?

ACKERMANN: Well, my anxiety is from forgetfulness. Each day it feels like a complete zero down experience, almost as if everything has to be learnt again.

MALOUF: Really?

ACKERMANN: Yeah. It’s always like that. Then it could take two years or even more to be able to see them or have a sense of what their newness is about. It’s hard to articulate why they had to be put through the grinder to exist.

MALOUF: For sure. Me too.

ACKERMANN: I like what you’re saying in the press release about beautiful paintings, because that’s always what I want to make. I want to make mischievous paintings that surprise me and are so entertaining that we don’t even need the audience. You’re very free-minded. You do what you want to do. You don’t care how it’s going to land.

MALOUF: That’s true. I’m trying not to be too funny, because funny art can get difficult.

ACKERMANN: Yeah. Your new paintings are not that funny, but still funny. Right now, you can’t openly entertain certain ideas because you can get canceled, right? So one must find different tactics. Like the pearl diver, the deeper you dive the more valuable the pearl you find.

MALOUF: Yeah. I was trying not to be too obvious, but it’s like that because with painting women, that’s a big thing. I realized that I was always painting women in the beginning. When I start a show, I just try to paint girls. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s something psychological. You always paint girls, right? Have you ever painted a man? No.

ACKERMANN: I like that you decided to paint women because it is uncomfortable for you to paint the female figure. It is the opposite problem I have; I’m really not comfortable with the male figure. Did you paint these women from like, an inner vision?

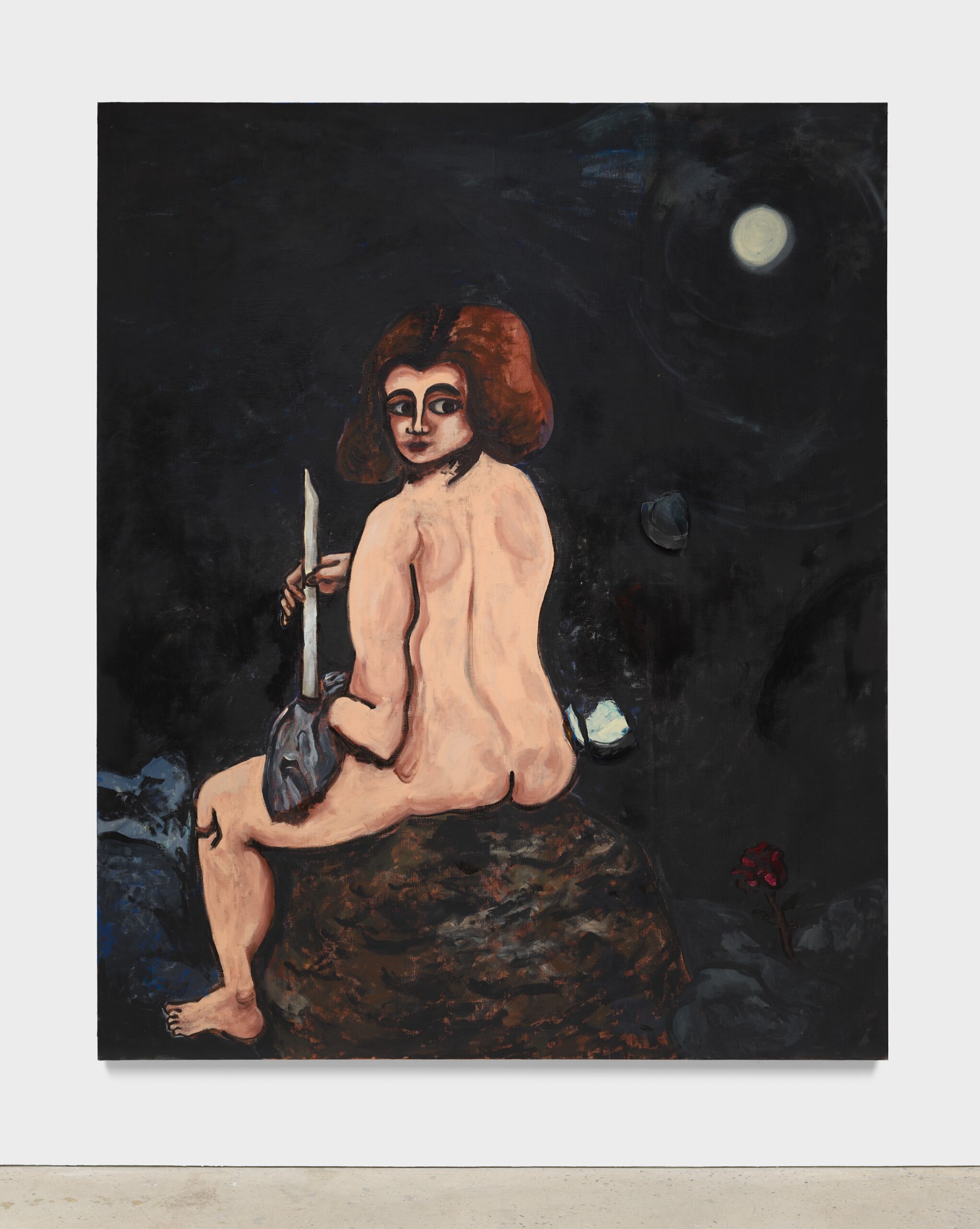

Mathieu Malouf. The Venus of Sardinia, 2023-24. Oil and ceramic plates on canvas 76 x 86 inches (193.04 x 218.44 cm). Courtesy the artist and Nahmad Contemporary, New York. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

MALOUF: Some of them. Some of them were redone 30 times because they always looked really grotesque and weird. When you paint a woman, she can’t look too crazy or it’s insulting. My wife Heji [Shin] would walk in, and she’s so sensitive to women looking grotesque, so that was almost the main driver. Maybe that’s why the paintings are not too funny, because it’s an obedient husband show or something.

ACKERMANN: That’s really cool. I can tell that you really worked on them a lot.

MALOUF: Yeah. Some of them are like [William-Adolphe] Bouguereau.

ACKERMANN: They look Byzantine and baroque all at once. The new 10 paintings that you’re working on now, are they the continuation of these paintings of women?

MALOUF: Yeah, I’m still painting women because there’s tons of paintings that I didn’t get a chance to finish for the show.

ACKERMANN: I must admit that they remind me of [Francis] Picabia’s badass women. They were painted in different styles but all were bold, sexy and outgoing. Sometimes he pushed them so hard, not worrying whether they would be loved or hated. And when they caused public outrage, he was devastated and overpainted them all. He couldn’t help but follow his instinctual urge to paint whatever he wanted. Your ladies remind me of that urge of painting harsh, thick black contours around a figure full of softness and grace.

MALOUF: They’re very harsh because I don’t really know how to paint.

ACKERMANN: In my earliest paintings I just wanted to work with contours. It was satisfying to make this very clear contour around the figures like those old Walt Disney black and white cartoons. They were whimsical and strictly defined in two dimensions at once.

MALOUF: It’s very fun to do that. You don’t paint women anymore?

ACKERMANN: I do and don’t. It’s a larger force than my will, what I make. I’m not very good at articulating how and why I make art.

MALOUF: Me neither.

ACKERMANN: But it’s not really women or girls that are in my paintings. They are like models or characters.

MALOUF: Totally.

ACKERMANN: They become these characters, and it’s very hard not to put them on everything in front of you, like doodling in your book or suddenly on a tablecloth. The problem is that I like to put them everywhere, almost like a cat that goes around and marks their place.

MALOUF: Yeah.

ACKERMANN: Do you notice that as you get older, you become more critical of your work?

MALOUF: Totally. You have to accept your old work, also. I was watching this Jeff Koons MasterClass that everybody talks about. Have you watched it?

ACKERMANN: I haven’t. Everything he says is a masterclass, isn’t it?

MALOUF: Kind of. The more I listen to it, the less I understand. He tells you how to become an artist. He says, “Go to Walmart and get a binder. Then get some paper and print out stuff you like. Look at the stuff you like and that’s it.” And I thought, “Yeah. Why not? I’m going to be doing nothing productive for a while anyways, I might as well put everything in a binder.” But then he says this weird thing. He’s like, “Everything you’ve done until this moment is perfect and you’re amazing and nothing you’ve ever done sucks and that’s how you’re going to move forward.” You have to accept everything you’ve done that you maybe don’t like so much.

ACKERMANN: But sometimes it is necessary to edit, no?

MALOUF: For sure.

ACKERMANN: Jeff Koons, he’s such a great enthusiast and optimist that it’s almost suspicious.

MALOUF: Totally. That’s why you’re watching it and you’re like, “Man, I don’t know if I can accept everything.” Maybe he means forgive yourself for anything you’ve done that you don’t like. It’s useful to forgive yourself.

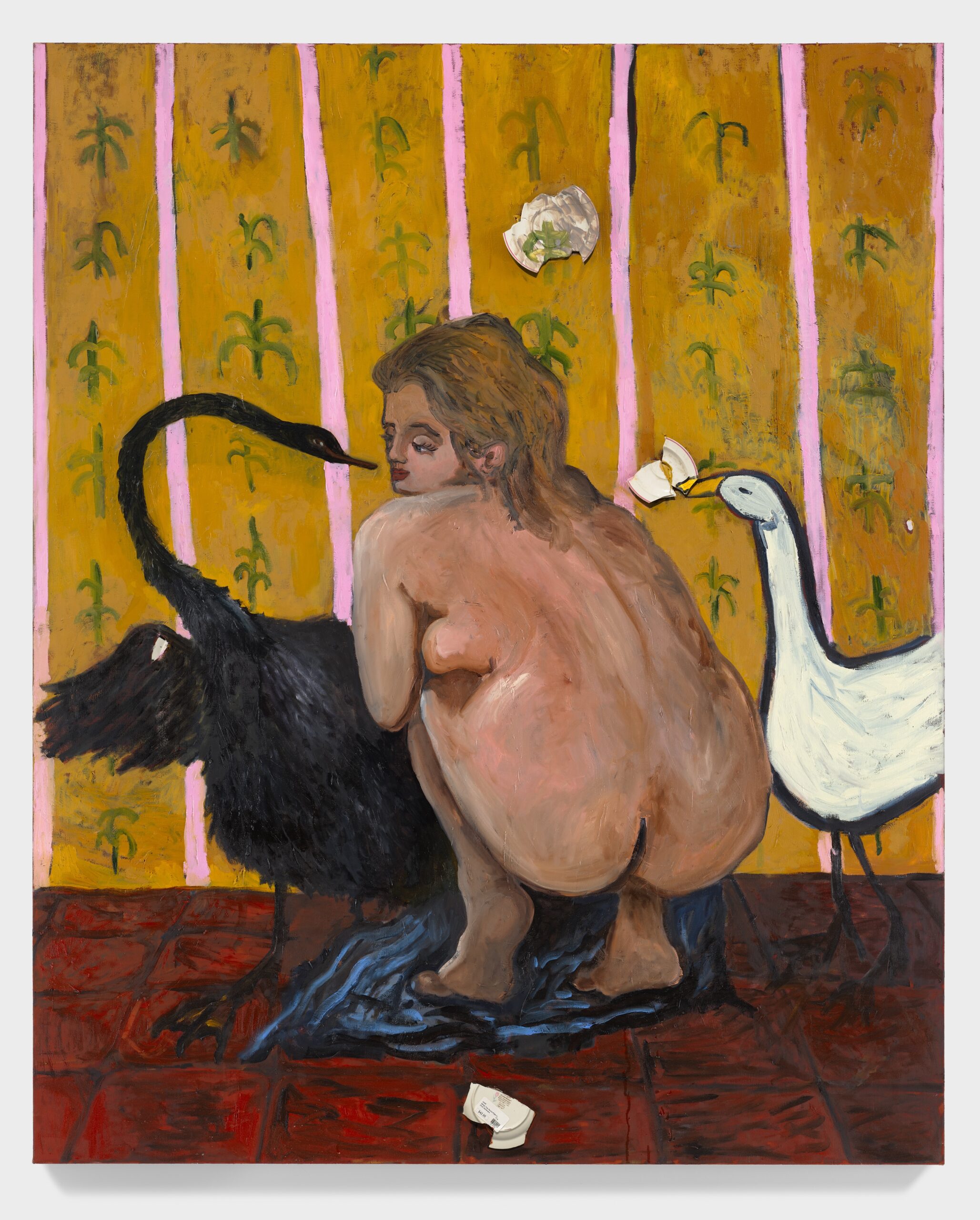

The Black Swan, 2023-24. Oil and ceramic plates on canvas 74 x 60 inches (187.96 x 152.4 cm). Courtesy the artist and Nahmad Contemporary, New York. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

ACKERMANN: Do you ever get bad reviews?

MALOUF: I was really mad for years that I never got bad reviews because I did shows that were almost intentionally bad. I either got nothing or good reviews. I want bad reviews. Do you?

ACKERMANN: Yep. I even get angry ones. I’ve been thinking about collecting all my bad reviews and making an illustrated publication out of them.

MALOUF: You have to do that. That’s really cool. It’s so nice to read bad reviews.

ACKERMANN: Do they still exist? I stopped reading the New York Times ages ago, not to mention all art publications. The last condescending review I had was in 2016. Nowadays, I’m noticing that either you don’t get a review or they’re all very positive.

MALOUF: Yeah. If there’s a bad review, it’s a gift.

ACKERMANN: It’s a real gift. Because when you do, you get really fired up about protecting your point. But of course, in the back of your mind, it’s bothering you to the extent that you want to fix what is being criticized.

MALOUF: Completely. A bad review totally fixes the problem of having to forgive yourself, because somebody else took the offense. Maybe I was looking to offend people so much that I never got the satisfaction of having a bad review. I got smear pieces, where it’s not really shitting on the exhibition, it’s more denying that there’s even work there. Talking about other things like, “This guy’s an asshole.” But not taking the time to explain why it’s bad.

ACKERMANN: Does Jeff Koons get bad reviews?

MALOUF: I’m sure. Maybe they don’t bother with him because it’s too complicated. Maybe it’s a mix of people ignoring him and dismissing it completely.

ACKERMANN: Did your show Toxic Masculinity Fallout Shelter make people upset?

MALOUF: Some people. There’s curators in the show that were upset.

ACKERMANN: Some people might have felt lucky like, “Damn, I’m hanging right next to Donald Trump.”

MALOUF: Yeah. Stefan Kalmár was pretty unhappy. Beatrix Ruf was unhappy, but she looked good in that painting. This guy, Richard Chang, bought it and he’s friends with her. The paintings move around on very personal and emotional terms with a show like that. I was really into doing stuff like that for a while.

ACKERMANN: It’s funny if the person can take it as a playful gesture, so we can all laugh without being punished for it. Real comedy needs to come back.

MALOUF: Yeah. It’s not super present.

ACKERMANN: But it is coming back because people are starving for the truth wrapped in good laughter. I noticed in your new paintings a sense of allegory. As you said, there is a hidden meaning.

MALOUF: Exactly. I used to be more satisfied with things that would make me laugh. The earlier paintings were more in your face. Five, six years ago, intuitively, I felt like doing paintings that were more aggressive. Maybe it just doesn’t make me laugh anymore or it doesn’t entertain me as much as it used to. I think I’m in a bit of a neoclassical phase or something.

ACKERMANN: Yeah, like the painting titled The Pastoral Concert. She’s so enigmatic. What is she holding?

Mathieu Malouf. The Pastoral Concert, 2023-24. Vinyl paint, acrylic, oil and ceramic plates on canvas. 92 x 76 inches (233.68 x 193.04 cm). Courtesy the artist and Nahmad Contemporary, New York. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

MALOUF: It’s supposed to be a flute. I drew it with my hands and then to put it on the canvas, I did this grid. I’ve never done the grid thing before, I just thought it would be funny. It’s very difficult. And then it’s all acrylic, like this vinyl paint called “Flash.” It dries immediately and it’s super matte.

ACKERMANN: The charming thing about this painting is that the grid messed up her anatomy a bit. She looks like a boneless creature, brute, but full of grace all at once. And now we know that she’s holding a flute, but [it looks like] a broken mop, which makes her a little shy and clumsy and transforms her from this Gothic nymph into a nude cleaning lady.

MALOUF: That’s really cool that you think it’s a mop. It’s the reason why we show paintings, I guess, so other people can look at them.

ACKERMANN: You can totally misunderstand. That’s what I’m hoping for so many times. In those misunderstandings, there is a chance that you see something, but then the other person sees something totally different in your painting. This woman, in so many ways she’s this peasant brute, but she has all of this grace in her. What is that iconic medieval face she has? Is it a Picabia face? Maybe she’s a pin-up girl, or a medieval icon? I don’t know. You have this double thing going. Then with the penguins, it’s the same thing. They are these complicated women.

MALOUF: Yeah. I have no idea what the penguins mean or why, but I accidentally took a weed gummy and I was super high and I really didn’t want to be. I don’t smoke weed or do drugs. I had this idea for the penguins from not being able to sleep. Maybe it means something psychologically, but I really don’t know what it is. But they’re fun to paint because they’re not too complicated. It’s not like painting a human being where you have to worry about whether people are going to identify it.

Mathieu Malouf. Untitled, 2023-24. Acrylic and ceramic plates on canvas 86 x 92 inches (218.44 x 233.68 cm). Courtesy the artist and Nahmad Contemporary, New York. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

ACKERMANN: They are musical penguins. They are always in this dance. Can I tell you my dream?

MALOUF: Yeah.

ACKERMANN: It was during New York Fashion Week and my paintings were walking down a runway.

MALOUF: That’s very cool.

ACKERMANN: I’m still thinking about the paintings walking on long, skinny legs.

MALOUF: That’s kind of a crazy dream. It’s a little bit like doing a show, right? When you do a show, it’s like sending your paintings on a runway.

ACKERMANN: Yeah.

MALOUF: Rita, thanks for doing this.

ACKERMANN: I’m not an easy conversationalist, but it was really fun talking to you.

MALOUF: Me neither. It was really cool. See you soon.

ACKERMANN: Bye. Thank you.