Talking Turk

For a life-long Londoner, Gavin Turk has a noteworthy history in New York. His American debut at the “Sensation” exhibition a decade ago at the Brooklyn Museum was “Pop,” Turk’s self-portrait as Sid Vicious drawing a gun from his hip. While it was Chris Ofili’s black Madonna cum elephant dung portrait that sparked Giuliani’s rage, “Pop” (1993) was a subtle stab at Warhol’s iconic Elvis-as-cowboy. Since then Turk has expanded his embrace of high and low material culture, cheekily selecting subject matter that when it comes out the other end as a Gavin Turk it is inevitably transformed into a humorous object. Nothing—from a discarded toilet paper roll tube cast in bronze to a glossy-black metal sculpture of a trash bag—is ever actually a ready-made, save for the idea: His art is in fact quite labor-intensive. During Armory week the Fine Art Society in London and Galerie Krinzinger from Vienna exhibited a range of Turk’s work from his take on Warhol piss paintings to a new sculpture directly inspired by Duchamp’s Fountain. Turk’s art seems as if it could emulate anyone or anything. For his current exhibition “Jazzz” [sic] at Sean Kelly Gallery, Turk has boldly taken on Jackson Pollock, creating a body of work that not only looks the part but he’s photo-documented himself with a balding head of hair in poses ripped from Hans Namuth’s famous photo series. It’s a reminder that Pollock’s supposed liberation of painting’s skill with the randomness of the drip was in fact artfully contrived. Without Turk we might not have anyone to excoriate the cult of artistic celebrity with such wit.

STEVE PULIMOOD: I remember when I first flipped to the back of the ‘Sensation’ catalogue I thought: Here’s the avant-garde and they all have resumes! When did you decide you were an artist? Was art school an important experience for you?

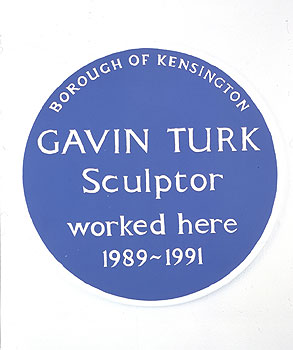

GAVIN TURK: In England you always had to keep the fact that you are an artist a secret. It was something that you did on the side. I eventually went to the Royal College of Art and after two years I put up this blue heritage plaque, which said “Gavin Turk, Sculptor: worked here 1989–1991”, and I did not end up receiving my degree. The tussle over this work of art managed to get in the press. I don’t think I ever really decided I was an artist. I went to college to learn how to think and look at art. In the end, I developed a more sophisticated misunderstanding of art.

SP: As a ‘failed’ work of art your notorious heritage plaque always makes me think of Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’, and its rejection from the Armory.

GT: I think Duchamp thrived on a certain type of rejection. One of the most incredible things about Duchamp is that he was somehow able to do all of the things that you shouldn’t do. His work should almost cancel itself out, but it doesn’t. It’s such a succession of accidents. He was so blasphemous, and yet he becomes a template for the idea of art in context … about the thoughts that happen before the work comes into existence. He a wonderful example—it’s not simply chaos—of an iconoclastic person who comes from inside the belly of the art world to create something that turned the art world inside out.

SP: How does Duchamp’s practice size up today?

GT: Even though we live in a different time, I don’t believe Duchamp’s work is closed. It is very poetic work. If you ever read the instructions of the ‘Large Glass’ he often talks about unrequited love and it gets wrapped up in an emotional package. He drifts in an out of my thinking and my approach to art. I don’t often systematically try to occupy that territory. I just try to learn from him.

SP: Did your artistic identity become the same as your cultural or real identity?

GT: When I was in college I thought of making up a fictive artist and giving him a name and a body of work. Eventually I came around to the idea of using my own name, which had this strange distancing effect, similar to using a found object. Being a Turk was quite interesting because in a sense it was like being a foreigner. It’s a short name, so graphically it’s quite punchy.

SP: Did you ever feel guilty appropriating an idea or image?

There was a strange moment when I tried to make the most humble painting I could by recycling all of its materials from found sources: Fabric from a tent; Hemp string to bind the fabric to the stretcher; I planted a tree to replace the wood that was taken. I hand sewed a panel in the corner that explained the various steps that I had taken to make this ecological painting. Across the middle of the painting was written my name. I don’t know if I felt guilty but I did feel I was giving the audience something that they didn’t really want.

SP: Or something that they did not know they might enjoy…

GT: There was a certain self-conscious barrier that broke with that work, but I had to use that disclaimer to tell the viewer that I had done everything in my power to use as little as possible to make it. I was questioning the value of the signature, which is a graphic conceit. As you walk around a museum, in a sense it’s just a hall of names, and you try to associate or guess the signature of certain painting styles… this is a Barnett Newman… this is an Ellsworth Kelly…

SP: But there’s a difference between style, its signature, and the incredibly bold move to literally put your own name writ large on a canvas?

GT: Well, it was sold and yes, I pushed these ideas until I became obsessed with the notion of signature, in terms of style and in terms of itself. I think of it this way: Take two paintings by the same artist—one has a signature and the other doesn’t. The signed picture is generally more valuable. The signature is almost graffiti or a tagging system, yet it can become more important than the subject. The artist has the power to signoff the work by deconstructing the work itself: I’ve finished this work now and I’ll sign it and relegate the painting to simply something that services my signature. The painting becomes the colorful backdrop of the signature.

SP: When you made the new Pollock paintings largely by repeating the motif of your signature—‘Gavin Turk’—dripped in paint, did you actually train to paint the way that Pollock painted? For example, did you listen to jazz?

GT: I did listen to jazz and, yes, I tried to paint like him.

SP: Have you always recreated the process? For example when you make the Warhol piss paintings do you throw a party and piss on the canvases?

GT: Pretty much!

SP: If you had to write an epithet for your own life what would it say? How could you possibly bring closure to a career that in many ways opened with the blue heritage plaque, which was practically an announcement of its end?

GT: I should work this one out… I dread to think! I don’t know. One good one said, “See. I told you I was ill.” Duchamp’s says, “It’s only the others that die.”

Gavin Turk’s “Jazzz” is on view at Sean Kelly Gallery through May 2. The gallery is located at 529 West 29 Street.