Looking At Food: Fanny Maugey

Fanny Maugey is a member of France’s developing culinary design movement spearheaded by former furniture designer Marc Brétillot, and a movement that’s more than fancy plate decoration or food photography. Culinary design uses food as a conceptual art medium, but never forgets the importance of taste to the overall effect. Maugey, a 24-year-old, Paris-based chef, studied at the Fine Arts Schools of Chalôn and Lyon and she is currently training for a degree as a “patisserie-chocolaterie.” She will have her photography work in a show in Bourgogne’s Chalon sur Saone this December, followed by an installation at Marseille’s “Salon du chocolat” in February.

Maugey’s restaurant experience includes the kitchen of the Musée d’Art Contemporain du Val de Marne and the cuisine at Grand Palais. As an artist, she creates elaborate interactive food installations including a refrigerated window at the Louvre’s Place Carrée, which was installed during FIAC 2007 to present ice-cream figures Maugey designed with artists Natacha Lesueur, Anne Delporte, Philippe Ramette, Laurent Millet and Frederic Dupra. Her creation was an orange slug. For an exhibition with the fall of Icarus as its theme, Maugey made a 4-meter wing from “glace royale” (that’s a mixture of egg white and sugar, usually used for cake decorations) which slowly melted during the duration of the show. At the Fine Arts School of Lyon, she displayed paper with intricate designs created with cooking oil and

For “Through the Looking Glass. Drink me! Eat Me!,” the culinary design exhibition presented by Marc Brétillot, Yannick Alléno and Vendôme luxury at the Hotel Meurice during the final days of Paris’s Ready-to-Wear shows, Maugey contributes an eight-square-meter parquet floor inspired by Gustav Caillebotte’s 1875 painting, “Les Raboteurs de Parquet (The Floor Scrapers).” The painting depicts brawny men laboriously scraping varnish from a dark wood floor. Maugey’s version is made from a different material – one that would be a joy to strip from the floor since her boards are composed entirely of dark, rich chocolate.

ANA FINEL HONIGMAN: The way that you describe culinary design sounds interchangeable from the conceptual, aesthetic and intellectual objectives of contemporary art. What are the salient differences for you?

FANNY MAUGEY: I believe that the main difference between culinary design and art is that culinary design has a practical function. Food has a utility. As culinary designers, our ambition is to create a new mode of existence for food.

HONIGMAN: What does a “new mode of existence” mean on a practical level?

MAUGEY: I think creative ways of eating can make us more aware of our daily relationship with food. Hopefully, it compels us to re-examine our eating habits, and our cultural habits

HONIGMAN: How does your work as an artist differ from your culinary design creations?

MAUGEY: I like working with materials that are fragile but also malleable like food. But I also like paper or beeswax. Wax is a very rich material for me. It’s close to food because you can melt it, heat it and mold it. It has irresistible sensitive possibilities. However, my art doesn’t have the utilitarian side inherent to design. My purpose as an artist is not to improve the quality of life or the quality of objects. I do not make my installations and sculptures to be reproduced, commercialized, and consumed. The art involves an inherent distance. You can see, smell, and feel my pieces—but you can’t touch them.

Parquet, Courtesy the artist.

HONIGMAN: What are the links between your practices?

MAUGEY: Even when I think about the form or the measurements for works like my chocolate parquet, I am also balancing these concerns with the ideas of an “ensemble” or what I call the gesture, “le geste,” borrowed from art. When I work with food, I work as both a craftsman and an artist. I try to connect the gestures of “l’artisanat” that I originally learned while getting a diploma of “patisserie-chocolaterie”, with the gestures of the artist.

HONIGMAN: What are artists’ gestures and how do they differ from “le geste” of a chef?

MAUGEY: Both contemporary art and cooking contain rather fascinating approaches toward preparation. Artists and cooks can be quite similar in how they discuss exploration, research, colors, textures and their working places. Both kitchens and the atéliers are places of an extraordinary creativity. I like to reference cooks’ ways of working in my artistic work. I like to represent cooks’ consideration of “mise en place” when preparing materials, tools and the rest. But what matters in both is the awareness of one’s decision to have an idea and push it to its conclusion.

HONIGMAN: What does art offer you creatively that cooking can’t?

MAUGEY: There is greater freedom to do what we want to do and greater opportunity for that freedom in art. Even if it’s finely decorated and looks delicious, food also must be tasty. If it isn’t, then it just won’t work. Art also allows artists to cheat. I can show you something and make you believe that it is something. Between the art piece itself and your senses, there are great gaps that you yourself fill with your imagination. Artists posses magician-type secrets that make art pieces compelling.

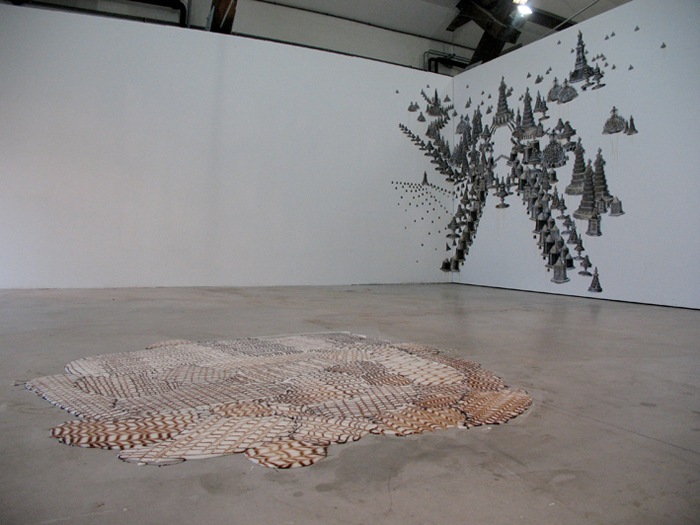

Installation shot. Courtesy the artist.

HONIGMAN: Do you think of your works as coming out of a tradition of still-life painting?

MAUGEY: There is a whole historic artistic tradition that I feel is

really close to my work and that nourishes it and that compels me to take

risks.

HONIGMAN: What do you like of contemporary artists like Pinar Yolocan, Anya Gallaccio, Jodie Carey or Farhad Moshiri who use food as their medium?

MAUGEY: I think that most artists using food as their medium are exploring issues of time and mortality—the different processes of decomposing, rotting or putrefaction. All these aspects are quite evocative but, personally, they are not what interests me most.

HONIGMAN: Do any artists working with the medium interest you?

MAUGEY: Well, actually I like quite a lot about Monaco-born French artist Michel Blazy’s work. Even though his works involve putrefaction, I think that Blazy’s work explores much more and opens new windows. He covered the walls of the Palais de Tokyo with carrot purée. The piece not only drew attention to the chemical manufacture of food but also highlighted the architecture of the space itself. It may seem paradoxical but I am most interested in work by artists using food who can transcend the symbolic or sensual associations with food to achieve another purpose. Then a real discussion can begin, which can lead to greater sensual and intellectual possibilities.