Inside the Actor’s Portrait Studio

Are headshots really the link between actors and their aspirations? Or are they contrived, pathetic little portraits, an expense of minor fiscal proportion and far more embarrassment? According to Berlin- and Brooklyn-based artist David Levine’s calculations, struggling actors spend, on average, $1,180 each year to have headshots made and distributed; each week roughly 10,000 headshots circulate among key points on the industry’s landscape in New York alone. Levine, a former actor, director and acting teacher himself, has put them to more refined purpose with a leading role in his artistic practice—even if the headshots themselves never got their actors their intended parts.

What could be an unflattering picture of a struggling demographic is in Levine’s hands a project characterized by affability, humility, and obvious empathy for people struggling to be recognized for their craft. For “Hopeful,” Levine’s second solo show at Berlin’s Feinkost Galerie, the artist will paper the gallery with more than 1,000 headshots and cover letters from his own evidence archive. Here we discuss what Levine hopes to achieve with his collection of other people’s ambitions.

ANA FINEL HONIGMAN: How do you think this show relates to general concerns within inter-personal relationships?

DAVID LEVINE: It’s about the ambition and vulnerability inherent in being social, and in trying to impress. You guess what someone wants from you, and you about trying to conform to a type while retaining your individuality-you’re never sure which of the two society values more. It’s about the notion of meritocracy, and the injustice of its promises; but it’s also about naivete, and jadedness.

AFH: Are actors particularly vulnerable to these issues or are they just following strict industry guidelines?

DL: I mean, can you really “blame” these people for taking the industry at its word? Really? All they want is for it to live up to its promises. I mean; it’s sort of about the acting industry; but really, we’ve all done this, in one way or another—we’ve all sent in something unsolicited to someone, with that same queasy mixture of hope and doubt and expectation and dread of judgment….

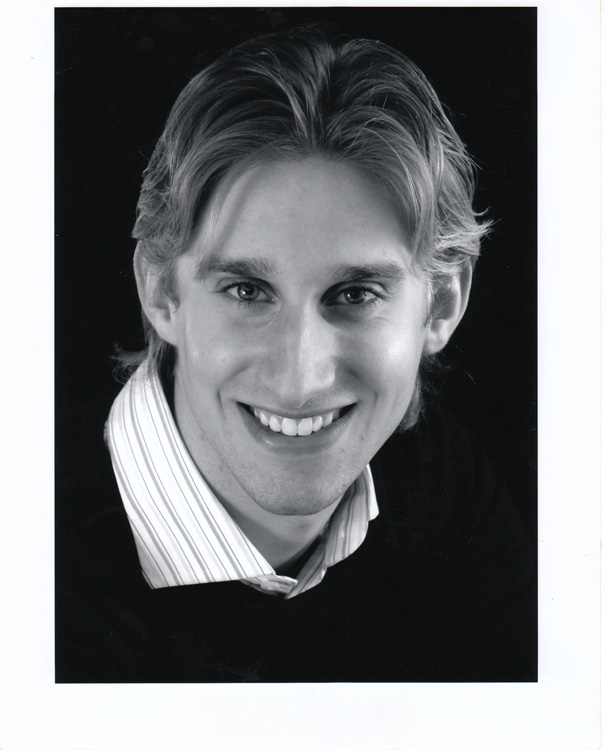

AFH: What do you think actors hope to convey with such contrived portraits? (LEFT: ARMY WITHOUT TITLE)

DL: It depends. Their overall suitability for a range of roles; or sometimes they send in different looks for different roles. But mainly their willingness to work; their awareness of the industry’s conventions…which is why they’re so disturbing when they guess wrong.

AFH: How do these things work or not work?

DL What you’re trying to do with a headshot is (a) catch an agent or casting agent’s eye, and (b) reassure them that you’re a safe bet to work with. Where many fail is on (b). The system is complicated. Casting agents put out calls to agents for particular types. The agents then submit their clients, via headshots, which the casting agents look over, alongside the director of the project. Then you bring a few actors in for auditions. That was the original idea. But the headshot somewhere along the line became a more basic, non-specialized form of currency, and agent-less actors started having them taken as a means of submitting to agents (and casting agents).

The other super-important thing is the resume stapled to the back. If the headshot gets my attention, and I flip it, and see that the person has a respectable MFA, or has worked with directors or theaters/producers I respect, I’m more likely to call them in.

AFH: Do you think headshots give enough, or useful, information about an actor’s appearance?

DL: It’s enough to get them called in for an audition. Most actors do look like their headshots, because it’s just bad policy to get yourself an audition and then show up looking like someone completely different. It’s not appreciated. But I think on a social level it’s kind of problematic, because these headshots in fact tell you nothing about the person. Their point is to conceal individuality, or to demonstrate how well someone can conceal their individuality. As you know, this relates to a long argument in portraiture about the individual vs. the type…and you find that a lot of actors carry that ability into their daily lives; which is disorienting. You wouldn’t want someone to look—or be—too much like their headshot. So I’m always kind of surprised when someone uses their headshot as their photo on a social networking site, or dating site—I mean; that’s not really you. That’s you in this weird, warped-out netherworld of hypothetical fame…

AFH: Besides for these projects, when has a headshot ever been useful to you?

DL: Never.

AFH: Now that you’ve found a use for them, what are you doing with them next?

DL: The project actually has multiple iterations. I’m conceiving a headshot book with Prem Krishnamurthy, which will be in four or five parts. I’m considering headshots, art historically, historically, sociologically, metaphysically, technically in terms of how to shoot the best ones. It’s one-part actors’ manual, one part art book, and one part scholarly text. If we can get it paid for, it should be a blast.

AFH: Personally, I’m fascinating by about author’s contributor photos or book jacket portraits and how the images authors select relate to their actual authorial voice. Are you considering expanding “Hopeful” to other examples of professional portraits?

DL: It’s part of a larger project, which isn’t just a book, of tracking unsolicited submissions across the entire field of for-profit cultural production. “Hopeful” is one expression of this project; another will hopefully be a year-long statistical study of unsolicited materials in New York City over the course of one year; another will be a photo portfolio of Walls of Shame photographed in situ in various agencies, galleries, record labels.

AFH: Is there really “shame” in knocking on doors to get your ambitions realized or is there another reason these materials make the “Wall of Shame”?

DL: The Wall of Shame is an archive of the most inappropriate or naive submissions to a given cultural gatekeeper. Every such office spontaneously creates such an archive—be it on a bulletin board, in a spiral binder, or in a file cabinet—for reasons I’m not entirely clear on, but it has something to do with shame, awkwardness, and worry about making false promises), etc. etc. etc. Ultimately this trash I’m collecting will get composted into some kind of raw form and be the basis for a public monument to hope.