STUDIO VISIT

Cristina BanBan is Getting “Raw to the Feeling” in Her New London Show

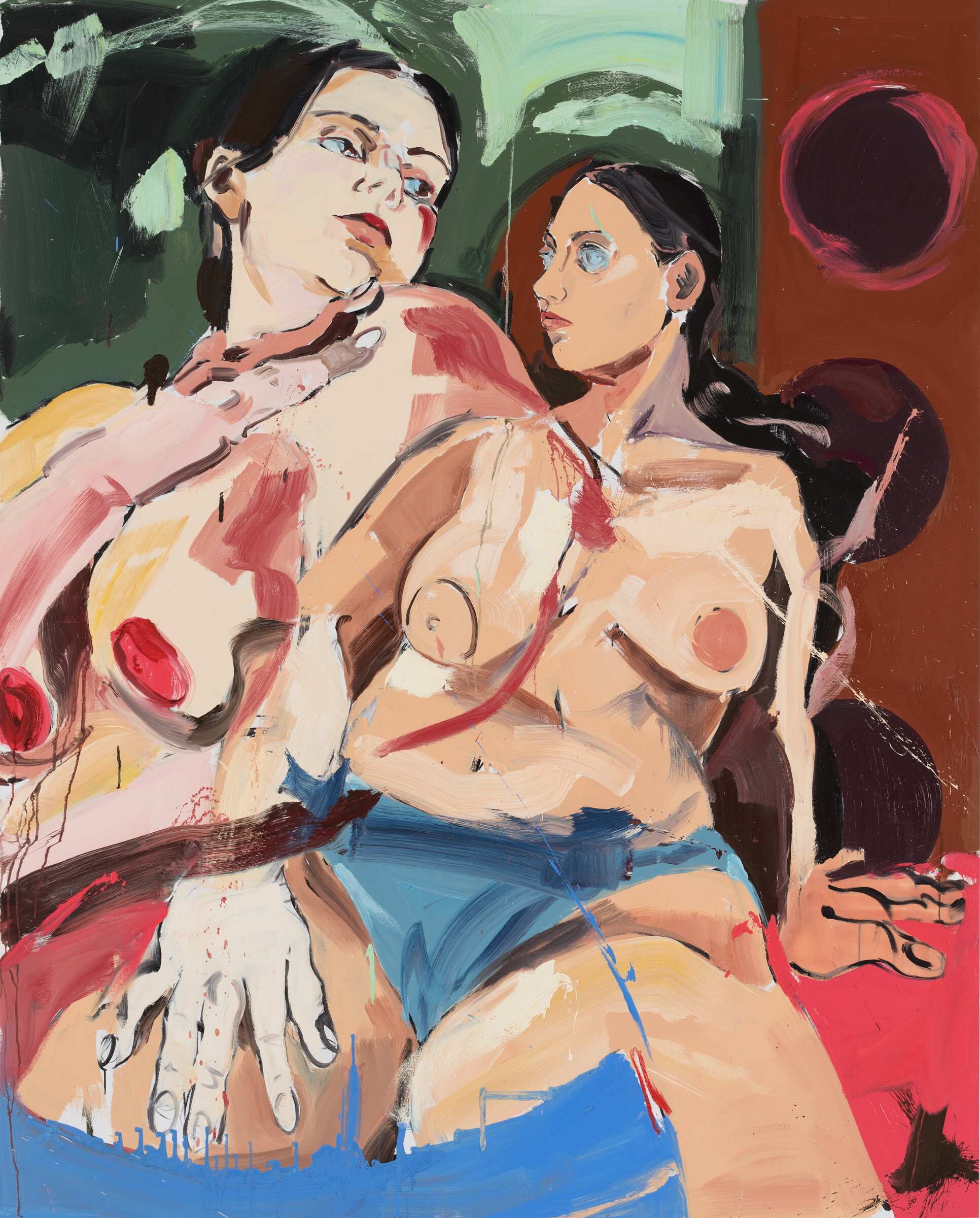

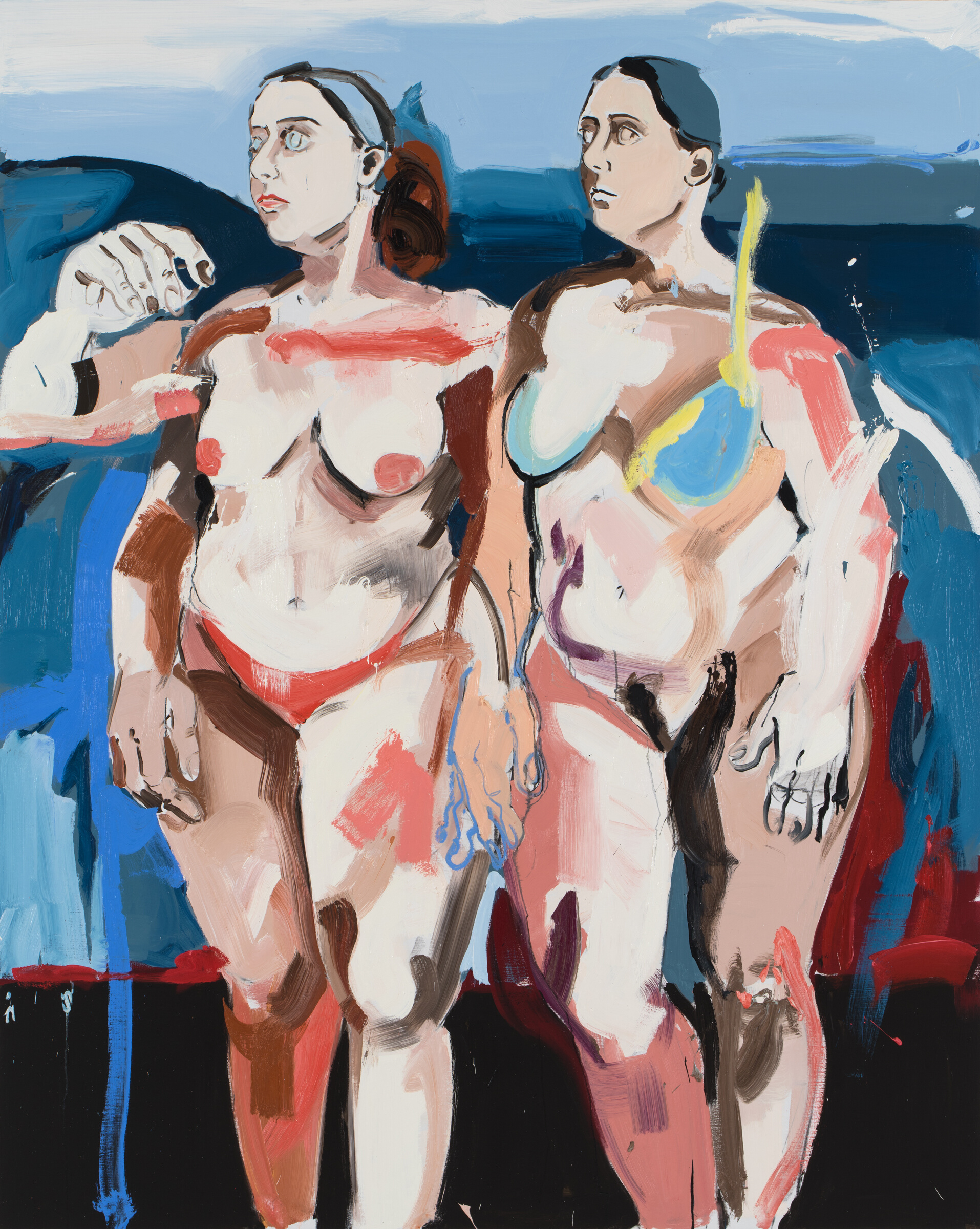

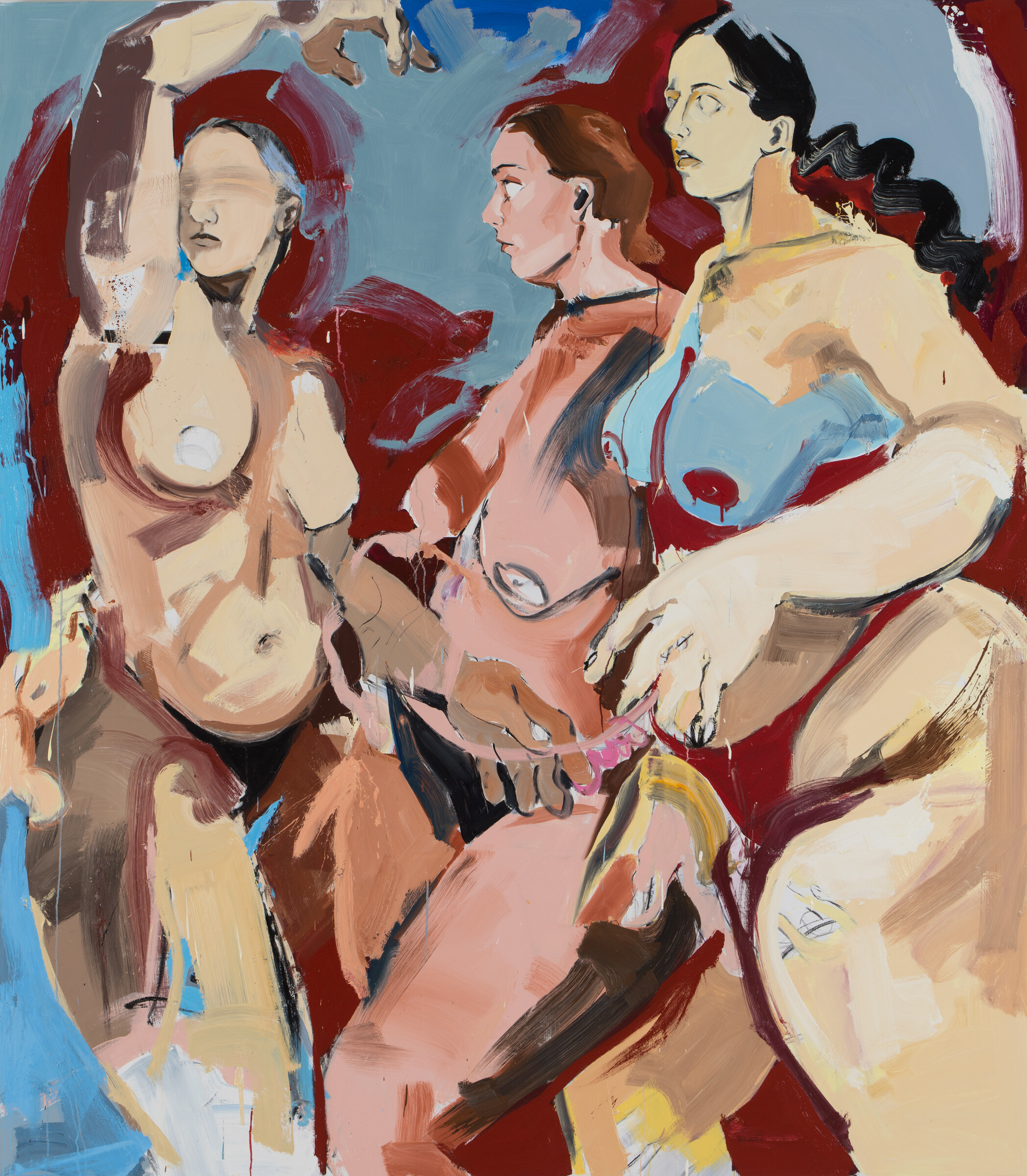

In Cristina BanBan’s loft studio in Bushwick, her paintings stand against the walls, unframed, their fleshy, vibrant hues contrasting the white of the sun-drenched studio. BanBan works on a large scale; her paintings are uniformly over seven feet tall. For years, her subject has been the female nude; showing women in various states of undress and repose, with the proportion of their bodies magnified. Multiple figures crowd the canvas, disrupting each other’s forms.

When I first visited BanBan at studio in 2022, she was preparing a series for a show at Perrotin Paris. Her latest series titled La Matrona, showing at Skarstedt Gallery this month, continues her trajectory from last year, when she began complicating her figures through abstraction and interrupting her subjects’ form by overlapping silhouettes and obstructing their line with swaths of color. Because of BanBan’s dynamic, embodied application of paint, the stillness of her studied figurative portraits roil with life. Recently, I met with BanBan to discuss her latest work and how she sees her style evolving.

———

MCDOUGALL: Last time we met it was not long after COVID, and you were talking about how memory and isolation had come into your work. I’m curious if now, in the intervening 18 months, that has changed.

BANBAN: For me, because I work a lot, I feel like a lot of things have happened in my work since then. I feel I’m in a completely different place. I think at that point I realized that I couldn’t keep up doing the same paintings where I would tell you a story and the paintings were narrative, where you could see a scene and you could read the painting in a more realistic way. It’s like, “Oh, fuck that.” I don’t want to do that anymore. What can I do? So the whole idea with my last two shows—one in Paris in March and the next one in October—was to experiment more. I think I’m getting away from the need to tell you something with my paintings and focusing on the materiality of painting and understanding the figure as a vessel to express myself. At times the paintings are becoming more abstract because I’m exploring different aspects of painting, like form and color. The pure concept of painting. If you remove storytelling, what is left?

MCDOUGALL: When I was here last, you felt you were right at the beginning of that exploration of moving the figure into abstraction or playing more with the form of painting. I remember in those earlier pieces, the bodies were overlapping with unfinished lines visible. But in this work, it seems like you’re playing with color a lot more.

BANBAN: I don’t really think about color. I prepare the drawing, but I don’t really prepare how I will approach the painting and the colors. This is kind of tricky to explain because I am in the middle of realizing what I’m doing. I’m in the middle of understanding my own practice. But last year, after my shows, my approach was to just focus on expression and the movement and how much I could push figuration. After I finished this, I realized they were very emotionally charged. I was talking more about the concept of figure and woman as a more universal topic, and I realized how painting is really emotionally charged. Maybe the colors and the process that I choose in the moment are all connected to what I’m going through in my personal life. Which is very emotional. I’ve been through some health issues, women-related issues. It’s a lot of pain. And I think in the latest paintings you can really see that. There is a lot of red and burgundy and I think, for me, it was a little bit dark. But this is where I am at the moment.

MCDOUGALL: How does movement figure into your process? Because you use yourself as a model and experiment in that way.

BANBAN: Well, I have to say that in this show I used two different models. It’s not me anymore, which brings new movement because everybody should bring you something different to work with. But I have to say that I realized they sometimes become a copy of myself, because still I do think I transform them. With the faces, like the jawline or the eyes, exaggeration of certain parts of the face to make it my own. It’s interesting because there is another body, but I feel sometimes you can see parts of my face. But for this show, yes, I used two beautiful models that helped me put this work together. The movement of the pose is still very classical. My starting point is very much the sitting, standing, and reclining woman. But then, in every painting, the situation will change. It depends how I feel like approaching it.

MCDOUGALL: And then in terms of working on the painting and applying the paint to the canvas, we can see the dramatic movement of you working.

BANBAN: Yes. Again, it’s very connected to my emotions. So for me painting is a kind of visceral function. I think you can really feel that in this series. Some of them may be a little bit more quiet. But it’s definitely common in all of these paintings. I have a certain velocity. I think maybe it’s a contraposition between the poses, which are kind of calm and relaxing, or pausing, where the way of approaching painting is much more rapid. I think it’s how I understand painting: when I see it, I act quickly because I like that energy to be translated to the painting.

MCDOUGALL: Long term, has painting become more active or dynamic or faster for you?

BANBAN: I think that as you grow more as a human being and you become more aware of certain things, you also become more aware of who you are as a painter. And I understood that I could feel that awareness translating into painting, to not give it a second thought. Almost like, more raw. I want my painting to be more raw to the feeling. Because if you think about it too much, the process takes you away from that primary feeling.

MCDOUGALL: Especially if you’re letting emotion be the impetus.

BANBAN: The drawing is more like a meditation, because I take the time to sit down. It’s more peaceful. Painting is the opposite. It’s more like the gut. I also learned when to stop, to understand each piece as a whole, as if it has a life on its own. So I don’t really like coming back to the painting to finish it or think about it while I do another painting. I let them be as they are.

MCDOUGALL: You’ve been working with the female nude for a while now. How do you think your work sits in that lineage? Or are you pushing against it?

BANBAN: I don’t think it’s my part to say if I’m part of it or pushing against the tradition, but I can say I use female bodies because, for my own sake, it helps me talk about my emotions. That’s why I use the female body. Obviously you can approach this topic in many different ways, like it’s a woman’s gaze painting a woman’s body, and that’s different from a man and the naked woman, of course. But that’s my answer. I think it’s more personal for me.

MCDOUGALL: What I find really beautiful is that the figures aren’t sexualized. There’s a different kind of intimacy in terms of a woman’s body, and a sexuality without it being about the sexualization of the body.

BANBAN: I don’t really understand why they would be sexual or sensual in any way. I think that pretty much comes from a viewer, rather than that being my intention. That’s never been my intention. So I think it’s very much about who is looking at the paintings. I think there’s a difference between making a completely naked figure and adding in some pieces of clothing and probably that’s why some people will understand the visual related to any sort of sensuality or sexuality, which has never been my point. But because they’re not completely naked, maybe that could let you read it that way. For me, it makes those characters feel more contemporary and closer to my generation. It also just helps with color, adding clothes. Sometimes I will even add some color in the hair, which will look like a halo or a Spanish flower, and that will make you think about where they’re coming from. Anything you put in the painting that is figuration will give a meaning.

MCDOUGALL: Here, there actually aren’t a lot of explicitly contemporary details, like phones, as I’ve seen in your previous work.

BANBAN: There are very few details. Sometimes you will see some chairs or background ideas with arches for composition. But realism or figuration gives you so much meaning because our brains associate so quickly, right? I realized I erased parts of the faces, all the gazes, because it gives you so much information where these figures are looking.

MCDOUGALL: That overlapping of bodies, the way they were interrupting each other, I can see that still present. But many of the bodies are fuller, or more fully painted in.

BANBAN: They are definitely still there, because I build up the painting. But the technique has definitely developed. I’m still coming from that place so you can see how I build up those images, but the line is not as visible as before, so some figures will be more realistic, like the volumes of the skin, the flesh. And other times it will become more like a plain color with a couple of lines. I like to play with that.

MCDOUGALL: Hands still feel significant.

BANBAN: Yes, this is a constant. I still slow down on heads and hands for now, and I loosen up a little bit in the bodies. But I will say, I still need these two elements. They’re very personal in the painting.