Carl Andre

IT’S the POTENTIALITY OF BEING ANYTHING. ONCE YOU TURN SOMETHING into SOMETHING, ITS UNIVERSAL USAGE IS OVER. Carl Andre

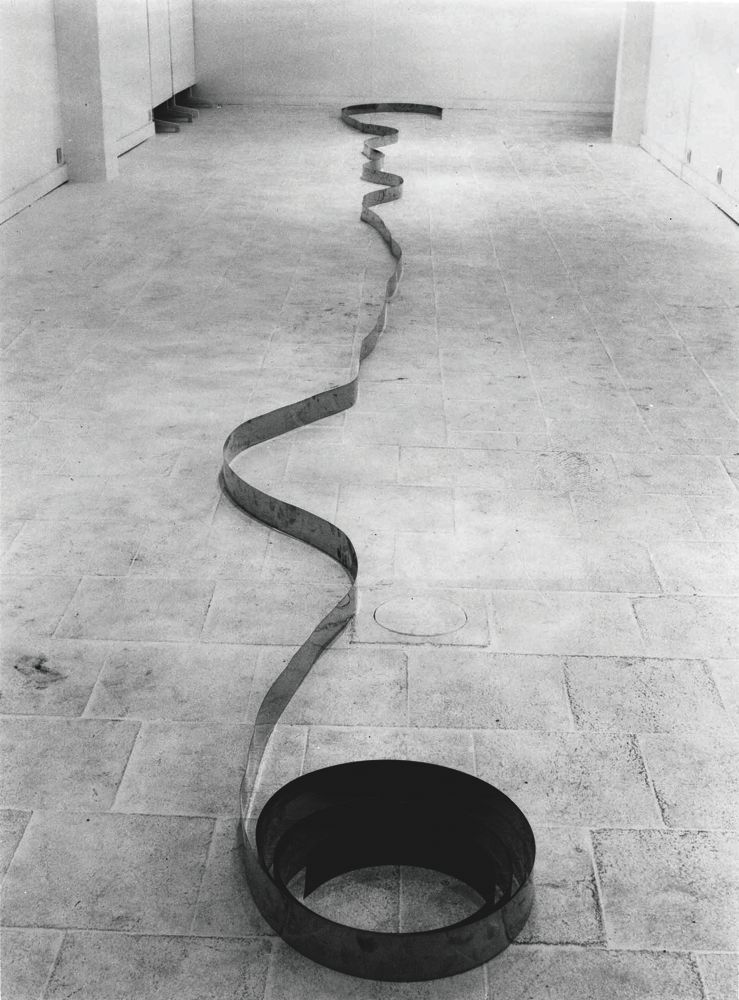

Carl Andre sought neither scandal nor success, yet he has experienced both. How could this happen? I suggest that both are the outcome of his having arrived at an extreme and original position as an artist and being both intelligent and strong enough to defend it. While sculpture in the past—whether carved, cast, or welded—has had a finite form, Andre thought of another definition: He strove for a three-dimensionality that depends on the unattached organization of modular elements in a predetermined configuration, which is often a grid rather than a finite fixed immutability. His materials are wood, metal, bricks, Styrofoam blocks, and even rubber truncated pyramids. These are, of course, materials used in building. Yet the way Andre appropriates them suggests we have not yet figured out what to build. It might also be taken for a criticism of contemporary architecture with its pretentious, overdesigned, eccentric facades and exotic, expensive materials.

Andre’s accumulations of untransformed materials can also be interpreted as a critique of sculpture itself—particularly its relationship to the verticality of the human body. Rather than confront the spectator with the traditional abstraction that mirrors the viewer’s own upright body, Andre organizes his modular arrangements horizontally. To see his work, you must look neither straight ahead nor up, as colossal public sculpture forces you to do, but down. This can be a disorienting experience. You are, in a sense, up to your ankles (and more occasionally your knees) in a Carl Andre.

Andre does not seek to engulf the spectator but to mark off his turf: he wants not intimacy but respect, which is the last thing given to artists when their work is immediately converted into a trading commodity. His metal plates hug the floor even more tenaciously than a carpet since they are glued to nothing—they can be picked up at will just as his pieces made of stacked wooden building planks can easily be disassembled. This was fortunate in terms of an early untitled piece made in 1965, created out of lightweight wooden two-by-four planks stacked into a square, in the center of which an extremely heavy industrial metal chain was suspended. I vividly remember the day I was visiting John Bernard Myers, co-founder of the Tibor de Nagy gallery on the Upper East Side, one of the first spaces to show Andre’s work. I recall the sound of the floor creaking and the women in the beauty parlor below shrieking that the ceiling was falling in. Indeed it was. Realizing that the entire weight of the stacked wood and the metal chain were centered on a single point, John and I rushed over and quickly took apart the wooden slats, distributing them around the room and allowing the chain to coil harmlessly across an area that could support it.

The common feature of Andre’s work is its provisionality—i.e., the fact that it exists as sculpture only at the time it is exhibited. Our knowledge of its precarious and temporary state, as well as our sense that the works can easily revert to their ordinary function, is part of their elusive content. Given its dual identity of being and potentially not being, Andre’s work clearly has a strong conceptual element, even though he was making it as far back as 1960, before conceptual art became a popular mind game. (In fact, I remember him calling for a “contraceptual” art at the time.) For Andre is able to demonstrate without academic explanation Bishop Berkeley’s observation that if a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it, then, for the purposes of empiricism, the tree did not fall. However, unlike Berkeley’s “immaterialism,” Andre claims no spiritual dimension in his art. Whether organized as sculpture or mutely stacked, his pieces maintain their identity as untransformed matter, thus proving Andre’s contention that he is a pure materialist. But not without ambiguity, which is why they maintain their tension and fascination.

It may come as a surprise that Andre, at age 77, is fond of quoting the Chinese sage Lao Tzu, but Andre’s close friendship and dialogue with the brilliant photographer and filmmaker Hollis Frampton, who, like Frampton’s hero Ezra Pound, was something of a scholar of Chinese philosophy, explains many of Andre’s fundamental assumptions. His aesthetic may be summed up in the advice of Lao Tzu: “A good traveler has no fixed plans and is not intent on arriving.” Like Ad Reinhardt, an artist Andre admires, in a totally permissive anything-goes and it’s-all-good culture, Andre is one of a handful of artists who say: No.

This interview was conducted this past May in Andre’s New York City apartment. One of Andre’s earlier works is being shown in this year’s Venice Biennale, and in 2014 a retrospective of his career is slated to open at Dia:Beacon in Beacon, New York.

BARBARA ROSE: I want to begin at the beginning, Carl, because I’m trying to reconstruct the remembrance of things past.

CARL ANDRE: That’s wonderful, but my mind has been destroyed by alcohol. I hope you understand that.

ROSE: Well, that was true when I met you. Do you remember when and where we met?

ANDRE: Yes! I was with [cinematographer] Michael Chapman. We were walking south on Broadway and you were walking north. We were supposed to meet and I said, “How will I recognize her?” And Michael said, “She’s the one who walks like a drunken sailor.”

ROSE: Michael used to say things to me like, “You have no sense of yourself.” And he was absolutely right.

ANDRE: But who wants a sense of oneself?

ROSE: I’m trying to conjure up the atmosphere of that time—except we weren’t in any sort of atmosphere. We were more out of the atmosphere.

ANDRE: Oh, let’s not talk about youth!

ROSE: Why? I thought it was fun.

ANDRE: It was fun! That’s why it’s painful!

ROSE: I remember we were all so broke, there was a great deal of scrounging. We had a ritual once you were gainfully employed. Every week, Michael and I would borrow $5 from you, and then we’d pay you back, and then on Monday we would borrow it back again.

ANDRE: That was around 1958, when I was making $30 a week working at the publishing company Prentice Hall. Prentice Hall was the cheapest place in the world. I quit because I was one day short to qualify for a vacation. So I said, “I’m getting out of here.”

ROSE: I remember the day you resigned. You came over and you threw your tie on the floor.

ANDRE: And my shirt and my pants and my underwear…

ROSE: No, just the tie. You stomped on your tie and said, “I resign from the middle class!”—which I thought was a good idea, because we weren’t in it anyway.

AN ARTIST, to ACHIEVE ANYTHING IN ART, HAS TO finally DO THE THING THAT NOBODY ELSE WANTS TO DO and NOBODY ELSE HAS THOUGHT TO DO. Carl Andre

ANDRE: You know how I got that job? I studied English grammar with Major LeVey in the Army. Major LeVey was a leading scholar in medieval Spanish ballads. I was in the “525 military intelligence school.”

ROSE: Didn’t you also plot movements of people on maps during the Army? I think you wrote letters to Michael about that. I remember when you got out of the Army and showed up at our door with a buzz cut. You were somewhat rotund then.

ANDRE: Oh, I’ve been fat, thin, fat, thin, fat, thin …

ROSE: This was more of a rotund moment. And you said, “I have my mustering-out pay. It’s $600 and we must spend it immediately!” We went to Times Square for two or three days and saw, I don’t know, six movies a day, and between the movies we drank.

ANDRE: Champagne!

ROSE: And after those six days you said to Michael and me, “I’ve spent my mustering-out pay …”

ANDRE: “And now you must take care of me.”

ROSE: And I thought, “How did this happen? I’m already taking care of Michael and now I have Carl!” I was 19 or 20, it’s the year 1957, and I don’t know who or where I am yet. I had no money. I was in graduate school and working odd jobs. Michael was writing short stories. He was a wonderful writer. He had been Lionel Trilling’s protégé at Columbia. I had no idea what you were going to do because you dropped out of college.

ANDRE: I would have dropped out of the Vatican if I were a cardinal.

ROSE: We were all sort of dropouts. We dropped out. We didn’t even turn on. We just dropped out.

ANDRE: And passed out.

ROSE: I had a friend who had a Park Avenue apartment. She would invite us all over to eat and drink and, at that time, Carl, you were composing a symphony for the piano …

ANDRE: Blanche et Noire … Because those were the color of the keys.

ROSE: I don’t think you ever even studied the piano. But you would sit in that apartment and play.

ANDRE: I didn’t study the piano—the piano studied me.

ROSE: Because you were often found under it. [laughs]

ANDRE: I had to see how it worked.

ROSE: You also worked for the railroad for a while.

ANDRE: I had a job on the Pennsylvania, which disappeared into New York Central, which disappeared into Amtrak. Anyway, none of us wanted a career in the business industry in those days.

ROSE: True. Everyone I hung out with was a manual laborer. Frank [Stella] painted houses in Bed-Stuy. My plumbing was done by Richard Serra and Philip Glass. And, you know, I never had any problems with my plumbing. I may have had some problems with Richard, but not my plumbing. And if people didn’t do manual labor, they drove a taxi.

ANDRE: I never drove a car in my life. Given my drinking habits in those days, I would have been dead a long time ago—stumbling out of a bar at 4 a.m. and getting into a car.

ROSE: I always thought you were witty when you were drunk. I only remember you as being adorable, affectionate, and funny.

ANDRE: That’s because I still had my clothes on.

ROSE: One day you did take your pants off, and you were wearing black women’s leotards underneath. I asked why, and you said, “To stalk the beast you must be dressed like the beast.” [Andre laughs] I remember so many of your quotations. Another one was: “In the marches of progress, why must I line the roads?” And during the Vietnam War, you used to say, “Make them eat what they kill.”

ANDRE: I didn’t make that last one up. There was a drunk at the old Cedar Tavern who said that.

ROSE: You make us sound so drunk back then, but we were also functional. Sort of … I didn’t go to the bars like you and Michael did. The Japanese word for wife is the thing that you leave at home. At that time in the late ’50s in New York City you might have called a girlfriend “the thing you leave at home.”

ANDRE: We went to bars to pick girls up. The girls you picked up from the bars were not the girls you took home to mother.

ROSE: Some people in the art world have taken you for a misogynist, which is absolutely not the case. You loved women and were very supportive of women, especially women artists.

ANDRE: I didn’t like men, but I liked women. I had a few close male friends, like Michael and Hollis [Frampton], but in general I didn’t like men because they were so physically competitive. Men are always making a pecking order. “I can beat you up and you can beat him up …” You can always find somebody to beat up. This goes back to the schoolyard. Most men would think, Don’t chum with girls. But I chummed with girls.

ROSE: True, you and I were good buddies. Then again, I was always your best friends’ girlfriend.

ANDRE: I wasn’t a stud, so I didn’t have to fuck every girl I met.

ROSE: This was when we were all in our twenties, still trying to figure out who we were. At that time, what was it that you wanted to grow up to be?

I THINK MY WORK IS very AMERICAN BECAUSE I’M AMERICAN. BUT I FOUND that EUROPEANS LIKE UNCERTAINTY and DOUBT. Carl Andre

ANDRE: A child.

ROSE: Well, congratulations. You’ve realized your ambitions. [laughs]

ANDRE: I did! I think it was Henry Moore who was asked where he got his ideas for his sculptures, and he said something like, “I continue to do as an adult the things I did as a child.” I think that’s what art is about.

ROSE: I think that’s true for all real artists.

ANDRE: Artists tend to be beyond embarrassment the way little children tend to be beyond embarrassment. They’re willing to do things which people—

ROSE: Are not supposed to do.

ANDRE: Exactly. Or haven’t done yet and don’t even recognize. “How can you call that art?” My life has been a chorus of “How can you call that art?”

ROSE: I think I remember you saying, “In the end, it will all be called art.” You also said, “Art is what we do. Culture is what is done to us.” That really sums it up. I don’t think today there is any real room for experimentation—certainly not here.

ANDRE: New York is dead. It’s too expensive.

ROSE: It’s completely dead. The only thing made in Manhattan is money.

ANDRE: When I came to New York, it was cheap!

ROSE: Frank used to say that you could live in the interstices between things.

ANDRE: Do you remember what we paid to live in the Viking Arms hotel [an SRO on 116th Street] in 1957 with a toilet in the hall? Ten dollars a week.

ROSE: And it was often hard to find that $10. But we did, among us …

ROSE: I remember we’d go to the West End bar a lot because it had a buffet.

ANDRE: And you could cash your checks at the bar.

ROSE: I remember Kerouac and Ginsberg being there. It was all guys drinking, and I would leave you and Michael and go home exhausted because I was going to school and working full time and cooking.

ANDRE: Somebody had to pay the rent!

ROSE: That’s what girls were for. The West End was very different from the Cedar bar though. The Cedar was all about bullies and punches.

ANDRE: I got there at the very tail end of that. I used to drink with Bill de Kooning at the old Cedar bar, and he was the sweetest man in the world. But those artists had all become rich and they moved to East Hampton. If the Cedar was too crowded, we’d go to Dillon’s.

ROSE: Dillon’s scene was John Chamberlain and [painter] Neil Williams, and there was a good fight there every night. I remember a brief period when you, Hollis, and [Mark] Shapiro, a composer who worked at Nedick’s [a hot dog chain], shared one room with one mattress, and the deal was that Hollis slept on it during the day …

ANDRE: I slept in the sling chair … We didn’t sleep—that’s how we found the time to make art. In those days I was using the cardboards that came with your shirt when you had them cleaned. I made some wonderful drawings on them.

ROSE: Are you surprised your work has taken on great monetary value?

ANDRE: I would be richer if I had realized that, because I didn’t keep anything. Very little. I had no place to put anything. I would give my sculpture away because I had no place to put it.

ROSE: There was that painful incident when Frank and I went to Spain on my Fulbright and Frank let you borrow his studio. You were making wonderful timber pieces. We came back and the studio was full of Carl Andres, and Frank couldn’t get to his paintings. So Frank said, “Carl, if you don’t get this stuff out of here, I will.” And since your work wasn’t soldered together but was simply stacked, one could stack them and put them back into their “primary state,” which was two-by-fours. So that did happen.

ANDRE: Frank cleaned them out.

ROSE: I said to Frank, “How could you do this?” And he said, “I told Carl he had to get this stuff out of here and he just never came. I have to paint and that’s it.”

ANDRE: Well, he was right.

ROSE: The good thing about it is that all your work could be reconstructed.

ANDRE: But isn’t it wonderful to be an artist whose works have mostly been lost?

ROSE: A lot of the work reverted back to its natural state.

ANDRE: Nobody wanted it!

ROSE: It was not in great demand. When was the precise moment you started thinking about arranging reclaimed metal and wood on the floor?

ANDRE: Actually, it started when I was a little kid. What do little kids do? They crawl on the floor and they build with blocks. I just continued to do that for the rest of my life. My father had a workshop in the basement of our house in Quincy, Massachusetts. There was a bin where the wood was stored and there was a bench, which had a box underneath, and all of the non-ferrous metals accumulated there—copper, brass, nickel. And then there was a box for iron and steel. Those were my tools when I was a little kid. So I never stopped doing what I did as a child.

ROSE: I want to hear in your words what the first responses to those works were.

ANDRE: Either antagonism or disbelief. And there were many of them. I remember for my show at the Tibor de Nagy gallery, Hilton Kramer, the art critic of The New York Times, wrote a review that said something like, “For those people who are aficionados of boredom, they should go to the Tibor de Nagy gallery in 1965 and see the exceedingly boring work of Carl Andre.” I thought it was very amusing. But Americans understand better than the Europeans and the English that any publicity is good. You read the reviews with a yardstick. Back then, attention was the most valuable thing of all. I’m not sure that’s so true anymore with art.

ROSE: Do you think Frank’s work had any effect on you in those years?

ANDRE: Well, as you know, he used to let me carve in his studio on West Broadway.

ROSE: That studio was so small you couldn’t step back enough away from the paintings to be able to see them.

ANDRE: Yes. And Frank sometimes left around scraps of canvas that were leftover that he was going to throw out. When he would throw them away, I would dabble with them, and use his paintbrushes to paint something. One time Frank came in while I was working and he said, “If you make another painting, I’m going to cut off your hands!”

ROSE: [laughs] I’ve never heard that story. So he turned you into a sculptor!

ANDRE: He turned me away from being a painter. But I was never good at painting. The great turning point came when I had a block of wood and I carved a shape into the wood and put a small piece of timber into that space—like a negative—and so it made an endless column, only inward. Frank came in and said, “That’s good.” And then he ran his hand around the uncarved back and said, “Carl, you know that’s sculpture too.” I thought what he meant was that the uncarved back was sculpture. Why carve? It’s a better sculpture that way. I’ll never improve the block. So I just started using uncarved blocks. There’s a Chinese sage named Lao Tzu who said, “The uncarved block is wiser than any utensil that can be carved from it.”

ROSE: The anti-Michelangelo.

ANDRE: It’s the potentiality of being anything. Once you turn something into something, its universal usage is over.

ROSE: There is an issue in your work of potentiality.

ANDRE: My works have always been unjoined. People were always making variations of my works, and I just said, “I don’t want to know.” You can’t put limits on those pieces. You can’t be there all of the time when they’re installed.

ROSE: Have their been forgeries of your work?

ANDRE: We’ll never know! Because of their identicalness. If you forge a Carl Andre, it’s just another Carl Andre. It’s not like a Vermeer.

ROSE: I recently saw a work of yours that I hadn’t seen before that consisted of what looked like narrow rubber tubing on the floor in a serpentine shape. When did you make that?

ANDRE: What I made depended on what I found on the street. At least in the beginning, my materials came from the street.

ROSE: In the late ’50s and early ’60s, there was so much junk on the street. Rauschenberg also got his materials by going outside and picking up whatever garbage was out there.

ANDRE: SoHo was called Hell’s Hundred Acres because it was full of sweatshops—without fire escapes. Completely not up to code. Every once in a while, these buildings would burn and 26 Puerto Ricans would be killed. Finally the city banned all occupancy, or the landlords raised the rents so high that the manufacturing moved to New Jersey, and the buildings were empty. That’s when artists started moving in, which was against the law.

ROSE: Until [Mayor John] Lindsay. He loved artists and he made way for artists in residence. But there was just junk all over the streets.

ANDRE: Canal Street had some really good places. On Friday nights, the ordinary trash cans would be full of metal scraps and ends, which could be squares.

ROSE: All of the artists were out there looking. Like Mark di Suvero.

ANDRE: But he was looking for the big stuff. I wanted the little stuff. We weren’t really in competition.

ROSE: Why do you think that European curators and collectors caught on to your work faster than Americans? Because even today a majority of your pieces are in European collections.

ANDRE: I think my work is very American because I’m American. But I found that Europeans like uncertainty and doubt. Look at the chaos of European history. Europeans cannot believe in certainty. But Americans believe in certainty. Americans think this can go on like this forever. Just as it is. No change.

ROSE: But America once had the idea of progress.

ANDRE: It seems with progress you gain certain things and you lose certain things. The automobile replaced the horse and buggy but you lost all of that nice manure. [Rose laughs] It was good fertilizer. And carbon monoxide is not good fertilizer.

ROSE: Did you ever have a patron?

ANDRE: I did get one. Vera List. She was wonderful. I did a gold piece for her. I told her that I needed whatever a pound of gold costs. Gold was only $35 an ounce then, because it was a controlled price at the time. Now it’s something like $2,000 an ounce. But back then you couldn’t own gold. You could own coins but you couldn’t have bars of gold. We were on the gold standard. I think it was Nixon who took us off the gold standard. Money is a very complicated problem. The history of money is very curious.

ROSE: I think of art today as similar to trading beads. We live in a potlatch culture where art is like sweet potatoes in a sense. The winner is the person who has the most sweet potatoes because basically it has no intrinsic value.

ROSE: Which leads me to this question: How do you feel about capitalism?

ANDRE: It’s inevitable. Because people are always trading their excess for somebody else’s excess. One country has a lot of aluminum so they trade aluminum for sugar. It’s the law of supply and demand.

ROSE: I have an idea I want to try on you. I’ve given your work a lot of thought and I think it’s really involved with movies in the sense that when you turn the projector off, it’s not there anymore. Once you pick up the elements in your work and stack them up, it’s not there anymore either. It no longer exists. It only exists as art at the time that it’s put together and presented. So, in a sense, it’s similar to film. When the light goes off, the film is no longer there. I’m curious why you have chosen to have a retrospective next spring at Dia:Beacon. It seems like you have avoided something big and permanent like that for some time.

ANDRE: I had one at the Guggenheim in 1970.

ROSE: You also had work at the Tate in London.

ANDRE: The bricks! [Equivalent VIII, 1966] The Tate was where I briefly became the most famous artist in the world because in 1976 The Daily Mirror in London, which was the biggest British paper in circulation at the time, had on Monday morning across the front page, the headline, “What a Load of Rubbish.” It was the brick piece! People started to say, “You’re just trying to sell me a load of bricks.” I was forgotten, but the bricks were remembered. You know, my grandfather was a bricklayer. I grew up in a brick house. What’s wrong with bricks? An Englishman took me aside and said, “You have to understand, all the bricklayers in England are Irish, and the English hate the Irish.” [both laugh] It was weird.

ROSE: It’s a perfect story. There are a lot of rumors that you have retired from making art. Is that true?

ANDRE: I’ve often stopped working for long periods.

ROSE: Because you were thinking?

ANDRE: No, I wasn’t thinking. I was hanging out and drinking as long as I could afford it, or as long as somebody else could afford it. Well, everybody’s thinking all of the time.

ROSE: I remember, of course, we were both deeply against the Vietnam War. We were really trying to stop it any way that we could. There was a party at Marion Javits’s house. She was the wife of the senator.

ANDRE: Yeah, she was very sexy … Or trying to be.

ROSE: She loved artists and would have these art parties. And Jacob Javits would be doing whatever politicians do. One day, we were all at a party and Javits walked in and, Carl, you were there. You took Javits by the shoulders and pushed him against the wall and said, “Why don’t you stop the war! Stop the war, Senator Javits!” Javits turned pale and crumpled up.

ANDRE: No, he said, “I try, I try.”

ROSE: Well, he didn’t try hard enough.

ANDRE: That war was deeply racist. I mean, the French were the colonists there. And then we set up a puppet government in Indochina after the Japanese left. They had a Catholic government in a Buddhist, Confucian country. Why was it being run by Roman Catholics?

ROSE: During that war, it just didn’t seem worth it to live in this country or make anything for this country.

ANDRE: Lots of people went to Canada. Lots of people went to jail.

ROSE: I went to jail.

ANDRE: I thought you went to jail for harassing a policeman.

ROSE: I went to jail several times. One time was about the war. You don’t know America unless you’ve been to jail in America.

ANDRE: I once made a work called American Decay, which I wouldn’t say I regret making, but it was the eve of Richard Nixon’s second inauguration and it was in the Max Protetch gallery in Washington. This was 1973. We lined the gallery with tar paper and I dumped 300 pounds of cottage cheese and 10 gallons of ketchup on top of it. And it stank. [laughs] I mean, it started rotting the second it was out of the container.

ROSE: And so did our politics.

ANDRE: The work lasted overnight. But it was hard to get rid of. How do you get rid of all this garbage?

ROSE: Another thing that’s remarkable about today is that there isn’t any real protest. If you can show it in a museum, it’s not protest. It may be politically correct, but that’s all it is. How do you feel about feminism?

ANDRE: I’m a feminist. I’ve always been in favor of women.

ROSE: I remember that many, many, many years ago you declared yourself a feminist.

ANDRE: I believe that woman are superior to men.

ROSE: That makes two of us. [both laugh] Many of your dealers have been women: Angela Westwater, Paula Cooper, Virginia Dwan …

ANDRE: But politics was not the core of my work.

ROSE: We wanted to change the world, which we knew probably we couldn’t. We didn’t like it the way it was and we wanted to change it, and we failed.

ANDRE: Well, the world is imperfect, and young people are always trying to perfect it and they always fail—which is a good thing. Who’d want to live in a perfect world?

ROSE: So are you making any new pieces for the retrospective?

ANDRE: I’ve been retired for some time.

ROSE: What about your piece that’s showing in Venice for the Biennale. It’s called Passport, from 1970.

ANDRE: It’s a xerox. One’s a black-and-white xerox, another’s a color xerox. There are different editions of it. I originally did that when I was working on the railroad and was laid off, as I would be periodically on furlough.

ROSE: You did once cause that train derailment.

ANDRE: No, I threw the switch and the engine went on the ground. You throw switches in the yard by hand to get the cars on the right tracks. It was exactly like filing. But I made Passport between jobs. I was idle. I just started cutting up the books and pasting interesting illustrations into it, and it had a kind of crazy narrative. There were pictures of girls occasionally and sometimes with their clothes on.

ROSE: You’ve always maintained that you are a materialist.

ANDRE: Oh yes, in every way. It’s not a bronze statue. It’s a bronze plate. It’s not representational. I’ve never been a representational artist at all. Most artists have been representational. That’s when you discover yourself, you know. An artist, to achieve anything in art, has to finally do the thing that nobody else wants to do and nobody else has thought to do. I was inspired tremendously by Brancusi, but I never wanted to make a Brancusi.

ROSE: Who is your favorite artist in all of art history?

ANDRE: Me.

ROSE: Who is your second favorite?

ANDRE: Brancusi. Or the Russian Constructivists, like Rodchenko. Lenin thought abstract art was a conspiracy by the bourgeois to demoralize the proletariat. Yeah, socialist realism!

ROSE: And Stalin once said, in the time of famine, let the experimenters live on their enthusiasm. We certainly lived on our enthusiasm.

ANDRE: Well, if you’re any good as an artist, you have to be doing something nobody else has interest in. Nobody would be interested in my work except a few crazy people.

ROSE: You also never had a studio.

ANDRE: Never. I was one of the first post-studio artists. I used to do my works in the streets. I used to find them in the streets, and I used to leave them in the streets.

BARBARA ROSE IS A NEW YORK– AND MADRID- BASED CRITIC. SHE IS CURRENTLY WORKING ON A BOOK ABOUT ARTIST AD REINHARDT.