New Art Dealers Get Ready for December

At a recent pool party hosted by the young art fair NADA at Canyon Ranch Resort in North Beach, Miami, a group of local collectors, artists, and visiting journalists gathered in an immaculate private condo. On this particular sunny Sunday afternoon, the serenity of this resort felt especially removed from the typical neon hedonism of South Beach art fare. Just as the event threatened to drift into Club Med territory, cacophony: with no discernible intro, the seriously obscure California band Psychic Ills, situated on their living room stage, puncture the air with an unholy multi-instrumental drone. As the eerie racket unfurled, band members remained hidden from view, clustered amorphously under gauzy sheets. Local artist Nicolas Lobo, like the rest of the audience, endured the furor for a few minutes, sipping wine from a plastic cup, then politely stepped out onto the veranda.

“NADA doing stuff here in the North Beach area was a really good and original idea,” Lobo observes. Like many Miami artists, he finds the South Beach scene predictable; though he maintains a studio in the art district of Wynwood, he prefers to perform and present his own work in less obvious spaces. He has enjoyed a fruitful relationship with NADA. “It’s the best fair and the best time to see what’s currently happening in other places,” he says. “Miami is always struggling to define itself as something; there is always the idea that somehow we will break out of our provincial past and finally be recognized as an international hub for culture by someone or something—somewhere out there.”

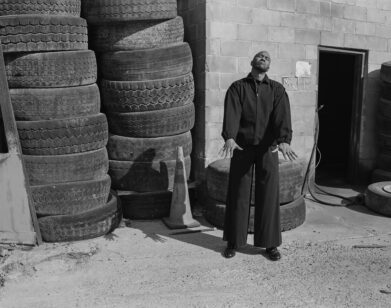

He sees Miami as something of a blank slate. “I’m happy to treat the city as a studio; it’s an empty, flat place, which is how I think a studio should be. I’m here because I want to be, not because I think it’s a good place to try and make it,” he explains. Indeed, much of Lobo’s work seems the product of a mind determined to escape the inconvenience of personal geography. His work, which might be considered outsider art in another city, is somewhat introverted, a highly individualistic filter through which he presents the aspects of pop culture that reach him. Experiencing Lobo’s art invokes a level of dream logic; on a subconscious level, the elements of Lobo’s work disconnect and reconnect to form a foggy new picture. An upcoming project—something of a deconstructionist approach to Warholian celebrity portraiture—involves isolating famous facial contour lines. It is be systematically disorienting: though it incorporates optical illusions, Lobo seems less interested in the hysterical sensationalism that defines the work of fellow Miami artist Romero Britto than casting a slow-burning synaesthesia upon his viewer.

“It’s something that can be applied to lots of things; a flavor, a movement, a color, an action,” he says of sensual experience. Relating his art to music, he is most influenced by an experimental 90s hip-hop style, called “chopped and screwed.” “I’m into screw music because it’s good, but also because it’s a certain kind of good that I think is creeping up in a lot of things lately,” he says. “In Miami I’m too far to relate to Houston, but I think what’s going on with screw right now is bigger than the sound or the place.” Much of Lobos’ work serves as a visual accompaniment to the screwed aesthetic, and serendipitously, his affinity for the music form happens to be timely, indeed. When “Limestoned”, his newest screw-influenced mixed media installation, opens later this month at Miami’s Charest-Weinberg Gallery, it will accidentally coincide with a widespread pop trend: the resurgent media popularity of the musical style’s late pioneer and namesake, DJ Screw. With the ascent of so-called witch house (aka drag), the syrupy urban hybrid that slows down R&B to a glacial, plodding pace, bands like Salem have lent chopped and screwed, and Screw himself, new relevance. In “Limestoned”, Lobo dyes igneous rock fabrications with purple cough syrup—a cunning tribute to the narcotic of choice for the robotripping drag crowd.

And as screw music’s Web 2.0 scions allow the genre’s impact to evolve beyond Houston, Lobo is toying with technology to communicate ideas beyond his zip code. He has even created a “party line,” dubbed “American Donut,” to explore pirate radio culture. Citing it as a way to “reconnect America” in an age of disconnect, it is partially a reaction to fissure he observes between Miami and the rest of Floridian culture. Transcriptions from the experience will be available via a vinyl release in the near future.

“LIMESTONED” OPENS NOVEMBER 30 AT CHARWEST-WEINBERG GALLERY IN MIAMI.