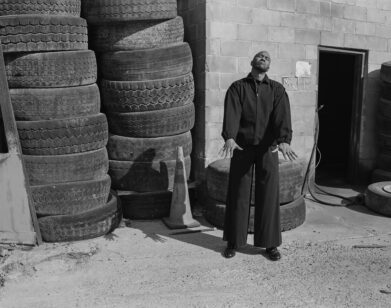

Adam McEwen

Adam McEwen wrote actual obituaries for The Daily Telegraph in London before he ever turned the genre into artwork, writing obituaries for still living and breathing celebrities like Kate Moss and Jeff Koons (he’s done nine in total and has three more on the way). Seeing news in an art gallery of someone dead who is still so obviously alive is like creating a black hole on the wall-which seems to be an effect that McEwen, age 43, now living and working in New York, is particularly good at making. His monochromatic paintings with blobs of dirty, chewed gum stuck on the canvases (some named after German cities bombed in World War II) work like meditation pieces on expectations. McEwen’s also been collecting text messages sent from friends and turning them into haiku-like riddles presented in graphite frames.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: When did text messages become part of your art?

ADAM McEWEN: I had a standard Nokia phone, which is the most common phone in Europe, and I got somebody to design a font that exactly matched my phone’s—pixel by pixel. Because this context is so familiar and everyone sees it every day in its most banal function, you could surprise yourself with meaning. It’s the same thing as walking down the street and seeing a sign on a store that says sorry, we’re closed. The familiarity of that opens up the possibility of throwing in the unfamiliar.

CB: Are the text messages real ones sent by friends?

AM: They’re all real texts, texted to me or texted to friends of mine who’ve forwarded them to me.

CB: Text messages are conversation killer—they’re an ideal way to avoid talking. But you’ve framed them, turning them into bits of poetry and biography.

pay people to chew the gum. Students get 50 cents for each piece. Then we take the gum and make it dirty with street shit. I want it to be both elegant and real.Adam McEwen

AM: They’re saying nothing. They’re saying, “K, C U later,” with a smiley face after it. But in a weird way they’re strangely revealing. It’s like this weird language that’s evolved. People text anything from suicide notes to pleas of love to bitching at their little sister.

CB: Do you see any link between your text-message pieces and your obituaries? Obituaries are almost sacred texts—the last words on someone’s life.

AM: They’re both overly familiar formats. I want them to be democratic. An obituary in a newspaper is available to every reader. But obituaries are really biographies. They’re published and vetted and archived and referred to later. Text messages are much more personal.

CB: And for your obituaries, you choose famous people.

AM: I’m not really interested in celebrities so much-the works are more homages. But the person must be famous so the reader knows that the person is still alive. I’m interested in that brief second when you aren’t sure whether Bill Clinton is alive or dead. I only need that moment in order to disorient them enough to sneak through to some other part of the brain—to achieve that split second of turning the world upside down. The obituaries aren’t about celebrity. They are more mournful, more melancholy. In a way, they are accounts of certain people’s actions taken in an attempt to make their lives better. My first more Mcewen one was Malcolm McLaren. I still had a job writing obituaries for The Daily Telegraph then.

CB: Where do you find the gum for your gum paintings?

AM: I chew the gum. Well, I pay people to chew the gum. Students get 50 cents for each piece. Then we take the gum and make it dirty with street shit. I want it to be both elegant and real.