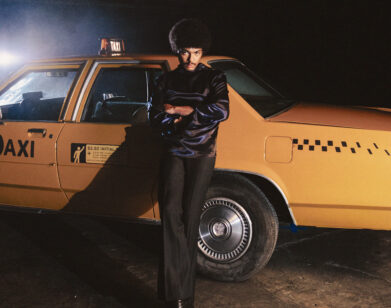

Thom Yorke

It’s an odd situation to just sort of start again without the big Radiohead flag, which guarantees this insane level of scrutiny. It’s nice to take it off, but it sort of throws you a bit as well. THOM YORKE

As far as rock-‘n’-roll stories go, the tale of Thom Yorke has a handful of conspicuous deficiencies: It contains no sex scandals or drug arrests to speak of and, at times, by design, very little rock-‘n’-roll. More than two decades have passed since Yorke’s band Radiohead emerged from Abingdon School in Oxfordshire, England, a well-mannered, cerebral crew—originally called On a Friday—that also includes bassist Colin Greenwood and his guitarist/multi-instrumentalist little brother, Jonny, as well as guitarist Ed O’Brien and drummer Phil Selway. They were signed when just out of college, scooped up in the A&R feeding frenzy surrounding the nascent shoegaze and Britpop waves of the late ’80s and early ’90s. Yorke, though, has never been an archetypal frontman—and Radiohead, never an archetypal band. Since first achieving notoriety with the grungily self-recriminating song “Creep” off their debut, Pablo Honey (1993), they have unleashed a string of albums that have consistently kicked at the conventions of both rock music and Radiohead itself. By popular consensus, the fulcrum is the group’s 1997 album, OK Computer, a complex, elegiac tour de force meditation on paranoia, isolation, technology, and yearning that has, among other things, yielded the oft-bandied declaration, “It’s their OK Computer“—a line frequently dropped by musicians who aren’t in Radiohead, people who read Pitchfork, and most egregiously, music journalists, to connote the arrival of an album by a band thought to be at the peak of their creative powers that at once represents the most challenging work they’ve ever done and the most them they’ve ever sounded. OK Computer was Radiohead’s OK Computer: the crystallization of an idea and the portal to another realm.

As much as the music, though, it has been the way that Radiohead has gone about their business since then that is at the source of much of the mystique. In an era that has seen the music industry become caught up in an inevitable death spiral and old-school rock bands become marginal entities, Radiohead has thrived—in large part, by doing things differently. As a body of creative work, what they’ve done both invites and defies analysis. In the aftermath of OK Computer, they appeared in a documentary, Meeting People Is Easy (1998), which managed to effectively capture both the mania surrounding the band at the time and, perhaps more than intended, Yorke’s growing disenchantment with it all. At the height of their commercial success, they cranked out Kid A (2000) and Amnesiac (2001), two distended, deconstructive, and difficult albums that strayed from the more accessible guitar-driven bluster of their earlier records. They left their label, EMI, after delivering Hail to the Thief (2003), and following a temporary hiatus—and with little advance notice or build-up—released their next record, In Rainbows (2007), on their own as a pay-what-you-want digital download (remarkably, the album still reached the top spot on the Billboard charts upon its physical issue two months later). They’ve flirted with the fringes, flitted with pop, toured in tents free of advertising, taken on twitchy subjects like the International Monetary Fund and the Bush administration, supported organizations involved in promoting fair trade, human rights, and environmental activism, tapped into the zeitgeist, run away from it screaming, and generally navigated the various triumphs and tribulations of being a band, rightly or wrongly, in their own, idiosyncratic way—whatever the rewards or the consequences. If Radiohead were one guy, he’d be Neil Young.

Over the years, Yorke has also gotten involved in a range of other extracurricular musical activities. He started DJ’ing—both on his own and with other people—and has worked with a diverse range of collaborators that includes both contemporaries like PJ Harvey and Björk and avant-gardists like the Los Angeles producer Flying Lotus and the German electronic duo Modeselektor. (If you want to know what Yorke is listening to at any given moment—which could be anything from Nathan Fake to Sidney Bechet to the Syrian artist Omar Souleyman—check out the impeccable “Office Chart” playlists that he posts on Radiohead’s website.) Yorke released his first album out from underneath the Radiohead banner, The Eraser, in 2006. Earlier this year, he served up another, Amok (XL)—this one credited to Atoms for Peace, a group consisting of Yorke, longtime Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich, Flea of Red Hot Chili Peppers, drummer Joey Waronker, and Brazilian musician Mauro Refosco. The outfit, which first convened in 2009, takes its Cold War-ish name from a song on The Eraser (which, in fact, borrows its title from a 1953 speech about nuclear technology by then-President Dwight Eisenhower).

Actor (and confirmed Radiohead-head) Daniel Craig recently caught up with the 44-year-old Yorke, who was in L.A. preparing to take Atoms for Peace and Amok on the road. The tour, which was set to kick off on July 6 in Paris, hits the States next month.

DANIEL CRAIG: I’ve never interviewed anyone before, so if I ask anything stupid, then just tell me to fuck off.

THOM YORKE: Okay … Sure. [laughs] You’re just outside New York, are you?

CRAIG: Yeah. I’m way upstate New York and sort of having a weekend. You’re in L.A.?

YORKE: Yeah. I’m rehearsing with the band.

CRAIG: Atoms for Peace.

YORKE: Yup.

CRAIG: You’re about to go on the road. Is it just the U.S. or all over?

YORKE: We’re going to go to Europe first, actually. We kick off in Paris. Sounds glamorous, doesn’t it?

CRAIG: I was reading somewhere that you’re just going to play smaller venues with Atoms for Peace than you would with Radiohead. Is that right?

YORKE: Well, kind of. I mean, people don’t really know who we are. It’s been a weird build-up because in calling it not me—in calling it another thing—people don’t necessarily make the connection, which is kind of mad. So it’s been sort of like starting again with a band and trying to say to people, “This is this thing.” And then I can’t really explain it either because it’s not really a band. So it’s more of a venues thing because we didn’t quite know how it was going to work out. Some of the venues are small and some aren’t.

I hadn’t figured out that bands and girls went together. I went to a boys’ school, and I didn’t realize that most guys join bands because they wanted to get girls. THOM YORKE

CRAIG: Are you hedging your bets, though? Because I’m sure people are going to flock to see you. I know that I’m going to. Are you doing all this because you feel like you can control it all more this way? Or does it just feel like the most natural thing to do?

YORKE: I don’t know if it feels natural. I mean, basically, it’s one of those things where I’ve got no idea what’s going on really—apart from the idea of having decided to do it at all. But you just can’t take anything for granted—and I’m glad I haven’t taken anything for granted because it’s sort of like putting on a brand-new face and still expecting people to recognize you. That’s how it’s felt. And it’s an odd situation to just sort of start again without the big Radiohead flag, which guarantees this insane level of scrutiny. It’s nice to take it off, but it sort of throws you a bit as well.

CRAIG: Aside from the collaborative aspect of it—and, I’m guessing, all of the wonderful things that come along with playing with a bunch of new people—is there something within you that wants to try other things because you feel like you need to do that in order to keep being creative and moving forward?

YORKE: That’s absolutely it. I mean, try to imagine this: I’ve essentially been writing music and playing with the same guys since I was 16.

CRAIG: I can’t really imagine it, but I can intellectualize it and guess what goes along with that.

YORKE: And you’re all boys and you’ve all gone to a boys’ school … [laughs]

CRAIG: How did music happen for you? I know how acting happened for me. Suddenly this thing appeared in my life, and I knew it was all I wanted to do.

YORKE: How did acting happen for you?

CRAIG: I grew up near Liverpool, and there was a really good theater scene there, so we’d go to the theater a lot. My mum knew directors and actors and people like that, so I’d get to hang around afterwards. That was very informative because I got to see the workings of it and how it all came together. I think that sort of ingrained itself in me. Then I hit 16, and I knew I wanted to do it. But we’re talking Liverpool in the early ’80s, so everything was as depressed as it could possibly be. Thankfully, though, I had a mother who was prepared to kick me out the door and say, “You’ve got to go and get on with this.” But in terms of music for you, and getting together with the guys and something happening, was that apparent right away? Or was it something that just happened over a length of time?

YORKE: Well, I had a similar thing to you, in a way, in that as soon as I was presented with music, that was it—that was what I wanted to do.

CRAIG: Was there music in your family at all?

YORKE: No, no. My poor parents could not get their heads around it at all. They have now—

CRAIG: Just now.

YORKE: Yeah, just last week. [both laugh] I wasn’t really able to read music or anything, but I just knew that I was very into it. The first teacher I met when I was at school when I was 11 was the guy who ran the music department.

CRAIG: This was at Abingdon. Was there a good music department at Abingdon?

YORKE: Yeah. Basically, I hid in the music department the whole time I was there. The rest of the system of the school—and I see this with my son now—was set up in a way that was very contrary to how I was built. I was constantly getting in trouble in small and annoying ways. So I hid in the music and the art department at every opportunity I could. I was so happy there because … Do you remember Thomas Dolby?

CRAIG: Yeah. He was an Abingdon old boy, wasn’t he?

YORKE: Yeah, and one of my first experiences in the music department was walking into one of the music rooms and there was Thomas Dolby, before he was Thomas Dolby, with this synthesizer that he’d built and all of this stuff. I was like, I want that in my life.

CRAIG: The Beatles were obviously a big deal in Liverpool, but with the traditions of bands like the Beatles and the Animals, the music scene in the northwest and the northeast of England were also seen as a way out. Music was seen as a way of succeeding—but also as a way of escaping from something. Was rebellion part of what drew you to music? Or was it just this strong feeling that you knew you had to do it?

YORKE: Oh, it was totally both. I mean, it was quite a weird situation in Oxford at the time because the only band that ever really happened back then was this little tiny indie band called Talulah Gosh, and they were about the opposite of rebelling. They wore anoraks and were super-straight and played this very strange indie music. But I would go to their shows, and there would be blood everywhere—people moshing, people fighting. And then this little dinky indie band onstage … It was not like a normal sort of “We’ve got to get out of here!” thing.

CRAIG: The ’80s being the ’80s, do you think that was a feeling countrywide in England at that time—that sort of thing of getting together in a mosh pit and just getting crushed? I mean, I remember doing that and it would just be the most exhilarating thing. It didn’t even really matter how good the band was—if someone could keep a beat, then you were prepared to jump up and down and smash around.

YORKE: Yeah, that whole bit was about just sort of going AWOL for the weekend and not telling anyone else where you were and finding yourself in these bizarre situations—which I’m sure I’m about to experience with my kids. But really, for me, a lot of the time that was kind of a pain in the ass as well, because it went with the territory and you couldn’t get away from it. I also had this peculiar thing where I hadn’t figured out that bands and girls went together. I went to a boys’ school, and I didn’t realize that most guys join bands because they wanted to get girls. I was not really focused on that the way everybody else was.

Record companies in those days were huge, huge empires. in L.A., there were all these dodgy hair bands and hookers and cocaine . . . It was all still going on like nothing had changed. Thom YorkE

CRAIG: Was that difficult for you?

YORKE: [laughs] I was just sort of geeky and not thinking about that. And with Radiohead, I’d been in other bands and done bits and bobs, but when I first met those guys, they were more serious—especially Jonny [Greenwood], who was younger, but he was this absolute musical child prodigy. He could pick up anything and play it straight off. He was in my brother’s band at the time.

CRAIG: Did you steal him, then?

YORKE: Basically, yeah. [laughs] I don’t think we’ve really settled it yet.

CRAIG: How did you get interested in the whole aspect of things? Were you into computers as a kid?

YORKE: Well, I came to the electronic stuff late because our band really was in the wave of rejecting a lot of it. When we were starting in ’91, ’92, there were some interesting things happening in Britain with electronic music—Warp Records was putting out some crazy shit. But a lot of the exciting things that were happening at the time were guitar music, and as band, that’s where we went. So we came back to the computer stuff later on. There was this interesting thing when we started out as a band where you had to go to a studio, so you were presented with a producer and an audience on the other side of the glass, and they called you and said, “Can you do that bit again? Can you try a different guitar?” And I always found that a bit weird because I felt that I should be with those people, in their room, doing that bit.

CRAIG: Not that you were trying to control the situation at all …

YORKE: No. It was just like, “Who the hell are you?” [both laugh] And then computers got to a point where you could just record directly into them. So when that happened, funny enough, I thought, Right, I’m going to learn how to do this because then I can understand that part. And luckily, we were working with our friend Nigel [Godrich], with whom we still work, and he was really into the idea that the areas were blurred. You know, as musicians we’re quite technical as well—especially Jonny and Colin [Greenwood]. I think Jonny actually learned how to program in C language along with my brother when he was, like, 12. I remember walking from my brother’s room in the morning and he was reading a book on how to program machine code. It was insane. That’s the kind of school we went to. I remember that the kids in school were freaking out when they could make the computer print the word “pee” or something.

CRAIG: We had computer studies at our school, but that’s about as far as we got. [both laugh] I suppose one thing that’s always fascinated me is that thing where you’re a band and you want to start recording and you get a label and a producer, and then there’s that pressure to go out there and really toil. Is that something that’s absolutely necessary to do—especially with new material, where you’ve just got to get it out there in front of an audience until you refine it and get it in shape?

YORKE: Well, we had an odd situation, really, because we went off to college and sort of put the band on hold. And then when we came back from college, we moved into a house together and started doing a few shows, and the next thing we knew, we’d come back from rehearsals or from a gig and the answering machine would have all these A&R men from these record companies trying to get a hold of us. It kind of just happened without us even noticing.

CRAIG: Did that excite you? Or were you suspicious? I’m asking because I know how I’ve felt in situations where suddenly it seems like things are starting to happen. I get nervous and sort of like, “Where’s this going? Where’s this going?” I still do.

YORKE: I was straightaway suspicious, like, “All you people just got on the program at once?” Because that’s obviously how it works rather than having that feeling of, “You know, maybe I am brilliant after all.” Instead, I’d say, “I can’t trust any of you people because you obviously all move in a flock.” But then we met the guys who were running EMI at the time in Britain, and walked into the offices of Parlophone and there were gold discs from the Beatles and Queen and everybody, and it was kind of like, “Shit, man. This is where we belong …” [both laugh] They had Pink Floyd as well.

CRAIG: Are you a big Pink Floyd fan?

YORKE: Not necessarily of all of their music but more of the fact that they were allowed to do just whatever the hell they wanted to do. And the guy who was running the company at the time had worked with them and he said to us, “I don’t expect you to do great things straight away, but I’ve got a good feeling about you chaps, so you just take your time.”

CRAIG: That’s an incredibly good thing to hear.

YORKE: I know. It was a big deal for us. It all changed eventually and got horrible and corporate and bought by an idiot. But at the time—

CRAIG: There were good people around.

YORKE: Yeah. It was pretty exciting. It was bizarre as well because record companies in those days were huge, huge empires.

CRAIG: They were still very much in control of the music industry.

YORKE: Yeah—and so old-school. They owned Abbey Road, and there were these flats in Abbey Road where the head of EMI would let us stay, and he would fly his Daimler or whatever it was—his big, black limousine—to L.A. when he came for meetings.

CRAIG: [laughs] Jesus Christ.

YORKE: I’m not kidding. The expense accounts …

CRAIG: The good old days.

YORKE: Oh, man. And when we joined, in L.A., there were all these dodgy hair bands and hookers and cocaine … It was all still going on like nothing had changed. We were like, “Wow. Really?”

CRAIG: And to think of that, obviously, in terms of the music industry and where it is now and the hiding it’s taken in the past 10 years …

YORKE: Which, to me, was much deserved—frankly—considering.

CRAIG: You think it’s for the better?

YORKE: Well, the only reason that the record companies still had any money at all is because they’d taken all the stuff they’d originally put out on vinyl and they found a new format, the CD format, for which they could charge double and turn the treble up and everyone would get it. So all of their music they resold again—that’s how they made a fortune. They didn’t actually have many new artists because they hadn’t invested in them. We were an … What is it? Anathema?

Everything went bang during OK Computer, and I didn’t really notice until such a point that I just started to become strangely catatonic. I’d come off stage and I could not speak. thom yorke

CRAIG: Anomaly maybe? I like anathema, though. I think it works as well.

YORKE: But EMI had actually stuck by us. We were lucky. They said, “Take your time.” They stuck by us when we put out OK Computer. They stuck by us when we put out Kid A, though I think they were kind of getting stressed at that point. [laughs] But it was very much contrary to what else was going on within our industry. And then, at a certain point, it just started to feel not like a nice place to be. So, to me, there’s no loss in the record industry as it was then disappearing, other than that they’ve taken a lot of the revenue for artists with it. The film industry is a bit like that as well, isn’t it?

CRAIG: Well, I think in the sense that everybody has been caught. It’s that crazy thing where everybody has been predicting for years how the industry is becoming more digitized and things are becoming more freely available and planning for how all that is going to work. Then they turn around and go, “Oh, god. We didn’t see that coming!” And you’re like, “Hang on a second. This has been in the cards for so long.” I don’t know that it will ever recover in a real way. Things are definitely changing. You know, I’m lucky. I make huge, bloody great movies that on the whole are, thankfully, successful. But that’s the rarity. What’s more interesting now is that the industry is freed up so that anybody can make a movie. I mean, if you’ve got two Canon 5Ds and the wherewithal, you can shoot a movie and cut it and edit it and get it out there.

YORKE: But then, much like the music industry, the big players still control how the work is distributed.

CRAIG: Things like iTunes, do you mean?

YORKE: I guess so. I mean, you can’t go past them and you can’t go around them, so it’s still in this weird situation where, technically, anybody can make something.

CRAIG: But unless you can distribute it and advertise it, which is the big spend … I’m sort of a nerd because I just play everything on vinyl now.

YORKE: Really?

CRAIG: Yeah. I mean, I play music in the car and I’ve got my iPod connected, but every time I crank up the volume, it just kind of distorts. So I went and got myself a decent record player and started buying all this vinyl. It’s funny listening to an album again from beginning to end, where you get up, turn it over. I think I tend to listen to less music that way, but when I do, I listen both more intently and more intensely.

YORKE: The form of the album is not something that is really looked at in the same way anymore—which, when that was first happening, I thought was quite cool, because I was sick of the restriction of the album. But now I hate it because I feel like it’s very difficult to get moved by an artist unless you are prepared to immerse yourself in what they’re doing completely.

CRAIG: Well, that’s true of music or any kind of art really. You have to put a little bit of work in.

YORKE: Yeah, and the fact that you can just scroll through all these different peoples’ work at one time like that is kind of hard. But there’s an upside to the digital thing from my point of view because I find that I have access to all this wacky, weird-ass dance-music stuff that I just can’t go into a shop and buy on vinyl. It’s much quicker and more fun when I’m DJ’ing to just turn up and have a little memory stick with it all ready to go. So there are good things about it.

CRAIG: You DJ’ed at Occupy London a couple of years ago.

YORKE: Yeah, I did it with 3D from Massive Attack.

CRAIG: We don’t have to talk about politics if you don’t want to, but I was wondering where your interest in something like Occupy—as well as politics and activism in the larger sense—comes from? Is it the anti-capitalist element? What is it about it that feeds you?

YORKE: I think it’s always been there with me. It was there right from school.

CRAIG: Do you think that has anything to do with growing up in Britain? I only ask because of how I feel. Socialism has become a dirty word—especially in the United States. We grew up in a country, though, that had a very strong socialist principle, but one born out of looking after people who otherwise might fall through the cracks.

YORKE: That was born out of the Second World War. The welfare state in Britain was this huge experiment—it had never been done before. I’ve just been reading about that—it’s very interesting because it was all tied up with the freeing of the markets. The rolling back of regulation of the markets was, to some extent, why fascism reared up in Europe anyway. So after the Second World War, it was pretty much a given—not just in Europe but everywhere—that the markets had to be regulated.

CRAIG: One of the simplest quotes that someone once gave me was “Money has no conscience.” It’s a classic thing where you can believe in deregulation, but does that mean you believe in 8-year-olds stitching footballs? Because that’s what the market believes in if someone’s prepared to do it. Now, a pure capitalist might maintain that the market will police itself—and maybe that was true in certain smaller areas. Maybe a city like London was built upon that principle.

YORKE: I don’t know about London. There was this documentary recently about London. You know why the city of London has become so powerful in the last 20 years? Because of offshores. We have all the old end-places of the empire and all these little islands that we are still linked to, which is how we do the offshore thing. That’s why so much money flows through the city of London—because of these weird little loopholes where money can just shift through, invisible, into the Cayman Islands. But it was during Thatcher and Reagan’s era that they really started to free up the markets to this level. Anyway …

CRAIG: Anyway … [both laugh] With Atoms for Peace, you’ve talked about the idea of moving on, which is an important thing. But Radiohead is still around—and I hope to god they are. Do you have a plan? Or do you just let it all happen?

YORKE: God, I so wish I had a plan. [laughs] The only plan that we’ve had recently was to take a year off, which was something that Ed [O’Brien] wanted to do. Ed wanted to go live somewhere else and switch off.

CRAIG: And have a life.

YORKE: Something like that, yeah. Just like, “Hey, how about we have 12 months where we don’t commit to anything at all?”—which is an interesting prospect.

CRAIG: And were you able to do that successfully?

YORKE: Well, of course what does muggins here do but commit to something else.

CRAIG: [laughs] Well, I can’t criticize that. Did the rest of the band manage to step back? Or have they got other things they’re doing while you’re doing Atoms for Peace?

YORKE: They’re all doing bits and bobs. Jonny has his film stuff as usual, which he really enjoys. Phil [Selway] is doing a record. I just can’t ever stop. Even if I stop, I’m very excited about the idea of someone saying to me, “How about you go do something for a few weeks?” Even if it’s only for a couple of days, it’s like, “Yeah, great,” because there’s always this mountain of unfinished chords and ideas and words. It’s always exciting because if everything else is going to shit, I’ve always got that.

CRAIG: Are lyrics a starting point? Or have you constantly got tunes in your head that you’re playing around with?

YORKE: It’s pretty much always tunes or melodic ideas or rhythms.

CRAIG: On Wikipedia, it said that [Queen guitarist] Brian May was a huge influence on you initially, so I stopped reading there.

YORKE: [laughs] Yeah, well, that’s too weird to believe.

CRAIG: I can change it for you if you want. But obviously, world music and dance music are big influences for you right now.

YORKE: At the moment, world music and dance music and rhythmic stuff and stuff that’s not just G-to-A-to-B-to-E minor …

CRAIG: You just described my guitar playing. [both laugh]

YORKE: I’m really into stuff, though, that sends you off a different way when you’re trying to write a vocal or things like that. But at the same time, I still really enjoy coming up with satisfying chord progressions that bring up emotions in you every time you play them. That’s what I was brought up on.

CRAIG: And that’s probably not going to ever stop being a part of what you do.

YORKE: No. It’s just like anything else where you feel like, “Okay, maybe I’m starting to get good at this …” That’s usually a good time to get away from it. If you’re actually starting to enjoy it too much, then it’s probably shit. [laughs]

CRAIG: Is that an English attitude? I feel that way about things—a healthy cynicism to make sure that nothing remains static.

YORKE: It’s like a little alarm bell in your brain.

CRAIG: Does that mean that you leave parties early?

YORKE: Ah …

CRAIG: No comment. Fair enough.

YORKE: What about you?

CRAIG: I’d like to be last to arrive, first to leave, but I’ve never managed to do that once.

YORKE: Even now, I stay to the end and watch the car crashes happen. But I’m not the car crasher anymore.

CRAIG: Oxfordshire is still home for you. How do you manage everything family-wise now?

YORKE: Much like with you, I have to spend a lot of time away. You spend your time committed to being in other places. Personally, I’ve become resigned to the fact that I come in and out.

CRAIG: And they forgive you, your family, for that?

YORKE: Oh, yes, totally. But, you know, it is a strange thing. Your kids respond to whatever is normal, and if they don’t have a problem with it and you don’t have a problem with it …

CRAIG: Do you take them with you on tour?

YORKE: Sometimes. I mean, a bit I don’t like, for example, is security guards taking them out into the middle of a crowd with 30,000 people. Something about that makes me a little flinchy—the idea that they see all these people going a bit weird or crazy or whatever, and they associate that with me … But they don’t. It’s funny because they’re completely immune to it because they’ve never seen anything else and it doesn’t mean what it might mean to their friends. It’s just like, “This is what Daddy does.” So it’s nice.

CRAIG: Did you struggle with the ephemera of it all? You know, you’re in a band playing music and then suddenly you’re the biggest thing ever—was that a struggle?

YORKE: It was a struggle. I guess everything went bang during OK Computer, and I didn’t really notice until such a point that I just started to become strangely catatonic. I’d come off stage and could not speak at all—and that was not just the exposure to the fame side of things. It was more like I had no concept, no understanding, of what the hell it was that these people wanted. I’d go onstage doing this thing, trying to fill this arena that I can’t fill because I don’t understand what this is. It’s like you’re given a job that’s beyond you. And it’s taken me years to realize what works in those big situations.

CRAIG: Are you enjoying what you’re doing now?

YORKE: Yeah. Around that time of OK Computer, I had a series of mini breakdowns where the public persona—this thing, this face, this person who writes this music … I would walk past that person in the mirror or listen to that person playing guitar and I didn’t know who they were. It was very odd, you know? You must have had that a little.

CRAIG: No, I completely relate to that. Did you talk to anybody? Was there anybody in the business who you could ask about it?

YORKE: Yes. Michael Stipe was around and he was amazing. He’s my really good friend still. He told me, “When it feels bad, just shut down. Be there but just shut down.” And then he also said, “Come on. Let’s go and get drunk with U2,” and things like that.

CRAIG: And so you did.

YORKE: And so I did.

CRAIG: Do you think it helped to go off and be a little more rock-‘n’-roll and have that experience? I’m talking from my own point of view now, but isn’t there that moment when you suddenly realize that if you’re not at least enjoying what you’re doing or getting some pleasure from it, then what’s the point?

YORKE: Absolutely. And then there’s something else that happened when the kids started coming along. When you’re a parent, then you still have to commit to this concept of, “Okay, I’m basically out of action now for three months.” So if you don’t commit to doing that when you commit to doing it—and then if you don’t enjoy what you’re doing when you go and do it—you really are screwed because—

CRAIG: It’s a lot of effort.

YORKE: It’s a lot of effort, and you’re not coming back with anything. You’re coming back damaged, rather than coming back and going, “Wow, that was fun. When can we do that again?” We’ve had lots of discussions in Radiohead about this over the past few years about, like, “Well, hang on. Who is driving this?” It’s a disaster if it’s the thing itself driving it. So we’re going to choose to carry on. We’re all big lads now—we’re all over 40—and we’ve all got a hell of a lot of other shit going on, so if we choose to do it, we’re basically doing it for ourselves and being selfish about it because otherwise we’ll go stark-raving mad.

CRAIG: Have you always managed to communicate well with the other guys? When you started off with Radiohead, the idea was that you all had an equal part in the band and shared equally in the profits, is that right?

YORKE: Pretty much.

CRAIG: Do you think that’s stood you in good stead?

YORKE: I hope so. It’s difficult sometimes. You’re used to being in a band, and there are roles that people can play or not play—someone is not involved in this other tune and they are involved in this tune and things like that. It’s a difficult balance, but ultimately it’s this weird creative framework, like a collaboration thing. Without everyone there, it’s not what it is—which sounds daft, I know. But that’s what’s interesting about working with a different band as well. You suddenly realize that you can’t really play with a bunch of guys if there’s all this extra shit flying around. You have to trust them. From what I know from talking to acting types—like yourself—you have a similar thing, maybe not so much in film, but in theater. If you don’t trust everybody on stage with you, then you’re in trouble, right?

CRAIG: Yeah. Or you can fuck with them, which is another way to go—and it might be fun but it doesn’t usually produce good stuff.

YORKE: I bet you’re really scary when you fuck with them, aren’t you?

CRAIG: [laughs] I wish. I’m very subtle. Maybe too subtle.

YORKE: Oh, really?

CRAIG: But look, I come from a theater background, which was about a collaboration, and it’s the biggest thrill I still get. I’m on a $200 million movie with a bunch of really talented people, and still, when things go wrong, fixing them and making them work is part of the pleasure. I get a big kick out of that.

YORKE: It’s hard sometimes. When you’re making a record it can be … I mean, to be fair, though, I do most of that with Nigel.

CRAIG: Right. You’ve been working with Nigel for forever.

YORKE: Since OK Computer. We had a brief sabbatical at one point, but that didn’t really work out. [laughs] But I’m the same in the sense that I get so bored when I’m working on my own musically. Technically speaking, one can work on music on their own—and people do—but I don’t find that very stimulating. Even if it’s only just one thing, one idea that someone else throws in my direction in the process of making something, it will make a massive difference. It takes you out of whatever creative patterns you have in your head, which is totally essential for me to doing anything that might actually be interesting and needs to involve other people.

CRAIG: So, at the end of an interview, people will sometimes say to me, “Is there anything I haven’t asked you that you want to talk about?”

YORKE: Yeah, and they get confused when you say no.

CRAIG: It’s like, “Why would I volunteer stuff? I’m British … Let’s go!” [Yorke laughs] So I won’t ask you that question. But this was fun.

YORKE: It was good, man.

CRAIG: Take care, and hopefully I’ll see you at the end of the year. Good luck with the tour.

YORKE: Thanks very much. I’ll need it.

DANIEL CRAIG WILL STAR ALONGSIDE HIS WIFE, RACHEL WEISZ, THIS FALL IN THE BROADWAY PLAY BETRAYAL, WHICH WAS WRITTEN BY HAROLD PINTER AND DIRECTED BY MIKE NICHOLS.