Remembering Adam Yauch

Dimitri Ehrlich:

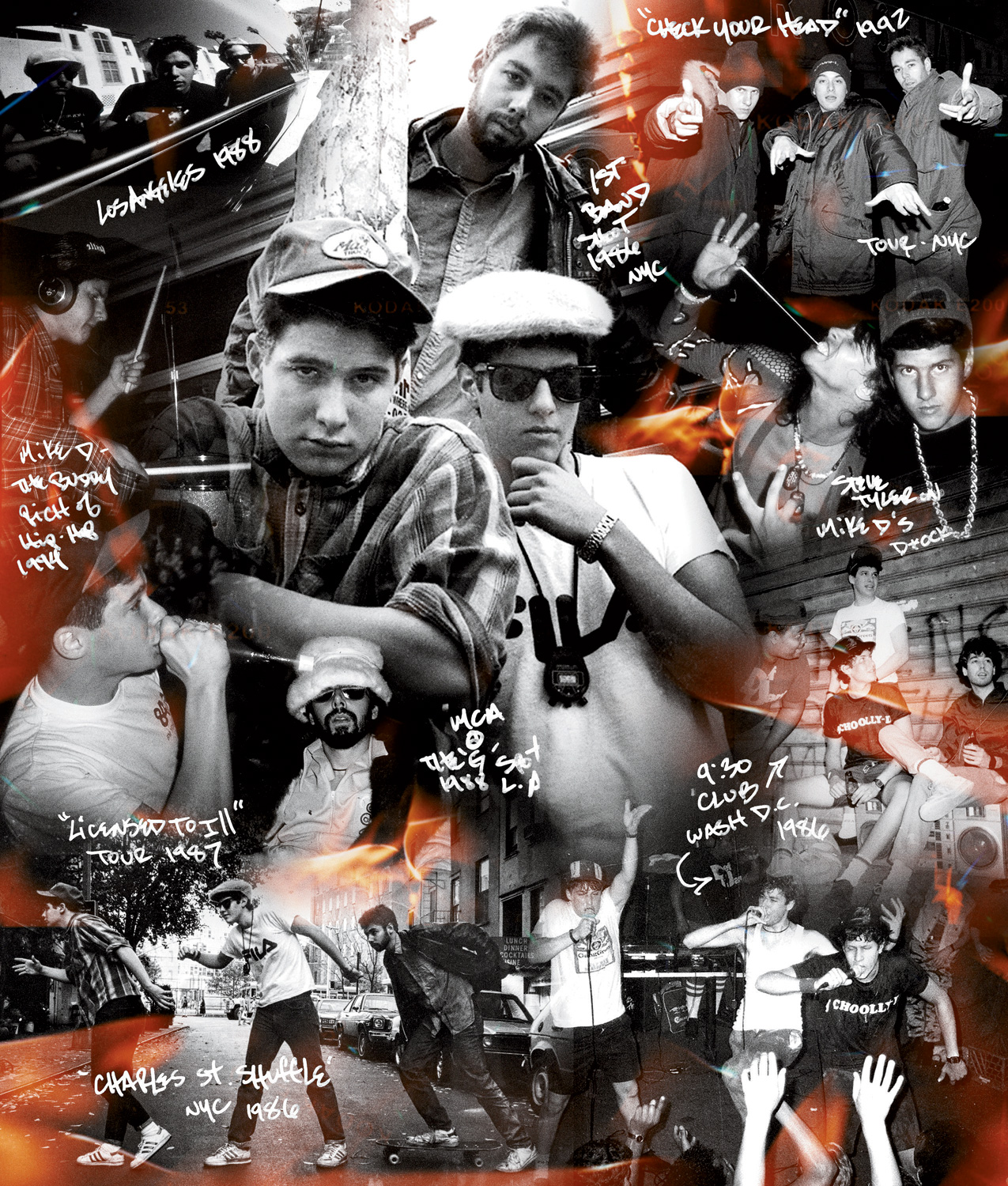

The first time I heard Adam “MCA” Yauch’s voice, my brother and I were driving on the highway in our parents’ station wagon. It was 1987 and “Fight for Your Right” came on the radio. “Who are these assholes?” I thought, angry, because I could tell they were way too much like me within hearing eight bars of the song’s snotty-nosed-smart-ass-streetwise-Jewish-kids-who-loved-black culture-too-much ethos. A few years later, I flew to Los Angeles to interview the Beastie Boys for this magazine. Mike Diamond picked me up in a BMW station wagon, and we drove first to Adam Yauch’s house and then swooped by to pick up Adam Horovitz. The four of us ate and talked at a diner in Silverlake, and then went to the Beastie’s studio. It was a cavernous room, with basketball hoops and skate ramps set up on the main floor, and their instruments (all thrift store purchases of vintage gear) on a stage. We jammed for about an hour, drifting like kids through quotes from the great funk hits of the 70s, me on guitar, Yauch on bass and Mike Diamond on drums. (Horovitz, better known as Ad-rock, just listened).

Over the ensuing years, our paths continued to cross: I interviewed Yauch again for this magazine, about his growing interest in Tibetan Buddhism, and shortly thereafter the band invited me to host the Free Tibet radio broadcast for their Tibetan Freedom Concert in Washington. I saw Yauch a few more times over the last decade, mostly at Buddhist events, occasionally just bumping into him on the street, and in 2009, when I heard he had been diagnosed with a cancerous parotid gland, I assumed his condition was treatable.

He underwent surgery and radiation surgery and radiation but Yauch didn’t show up when the Beastie Boys were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in April. And today, the news came: at the age of 47, one of hop-hop music’s most brazenly adventurous, funny, and curious explorers, had crossed, unexpectedly, to the other side. If what Yauch’s Tibetan Buddhist teachers say is true, he has entered a state between death and his next rebirth, known as the bardo, in which the recently deceased person’s mind is still aware and highlysensitive to the emotions of those left behind. In which case, perhaps the best way to honor, celebrate and help him is perhaps to put on “Fight for Your Right,” turn it up, and do what the song says. I think MCA would have wanted it that way.

Matt Diehl:

The passing of Adam Yauch today was one of those moments that shapes one’s life. This was someone who was both a larger-than-life voice of a generation, and an absolutely present, accessible human being. That dichotomy is what rang through my head today as I grieved (and continue to grieve). Like many significant moments, I will always remember when I first heard of Adam Yauch’s death: DJ Jason Bentley mentioned the news around 10:00 a.m. PST on his KCRW radio show “Morning Becomes Eclectic.” I immediately recognized the same kind of feeling I’d had when I’d heard John Lennon had died, and Kurt Cobain; the difference was, my connection to Yauch was much more personal.

I first discovered Yauch via the earliest recordings of The Beastie Boys: I was thrilled that someone was expanding punk’s lexicon by looking to subcultures outside its domain; I also recognized the genuine Noo Yawkiness of it all—and yeah, I just thought the lyrics were funny, too. Like many from each generation, I grew to have my own relationship with the Beastie Boys’ music: the revolutionary sampling of Paul’s Boutique, the embrace of live instruments anew on Check Your Head, and so on. What I really believe dazzled listeners, though, was the Beasties’ access to sheer imagination: they were a shining example of what kind of creativity could be untapped if you could just look inside your real self and capture it for that moment.

That’s the one thing that really struck me about hearing Adam Yauch’s own voice as MCA on Beastie Boys’ songs. In a review of the Beasties’ last album for the L.A. Times, I wrote this: “The album was delayed for nearly two years due to his struggle with cancer, but you’d never know that from MCA’s impactful delivery—his gruff rasp remains one of pop music’s most distinctive, electrifying voices.” It sounds corny to say now, but the greatest musical quality of Yauch’s voice was that it evoked an urgency: even when he was being offhand, the sound of his voice made you feel alive.

Being a journalist presents oneself with some unexpected constructs. On the one hand, I would parse the Beastie Boys’ music on a critical level to make sense of it in reviews and interviews. On the other, I got to know them, and Yauch in particular, just from interviewing the Beasties many times over the years, and from them being in certain of my social circles. I’m not saying that to brag about my proximity, or to say we were super homies. It’s more about actually seeing legendary greatness interact just as regular old human beings, and observing what comes out in the middle.

What came out in the middle for Adam Yauch was that he was probably an even greater human being than anything we knew from his public face. Yes, he was a great musician; yes, he was a dedicated social activist; yes, he was a spiritual seeker; yes, he explored his other passions (like filmmaking) with panache. But seeing Yauch around with friends in Chinatown, say, you’d see he was a great father, the way he was with his children. Sitting across from him at a mutual friend’s wedding, you’d understand that he wasn’t just a superlative rapper, but one of the great wits of our time: he always had a wry, dry commentary that really was the funniest comment on whatever was going down. I remember hearing that he didn’t want to bring takeout food into his house: he’d become so considerate of living things, he didn’t want to even consider taking the life of an ant that might be drawn to sandwich crumbs. He was fascinated by art and expression—graffiti, obscure videos, Star Wars, Enjoy Records 12″ vinyl, slang, classic sneakers—in all its forms; high and low, he did not discriminate. That’s how sensitive this dude was—it was not an act for this guarded, humble, introspective, yet in many ways, very open person. His authenticity was never in dispute—but Yauch didn’t just live up to the promise of his persona: he transcended it. Adam Yauch lived by example, and seeing him grow allowed us to grow along with him.

Yauch ultimately begat the Beastie Boys their greatest legacy: consciousness. When I heard the news of his death, I tweeted something soon after to the effect of “Beyond his revolutionary music, I was most impressed with Adam Yauch’s willingness to mature in public, and stick to his guns when he did.” Yauch grew up as a public figure, and took his following along with him on this spiritual and intellectual journey; again, it sounds corny to say, but that truly affected the generations that grew up idolizing the Beasties. One episode stood out to me, always: I helped do interviews for a massive Beasties oral history for SPIN that the article’s primary author, Alan Light, eventually turned into a book. One particular episode moved me then, and still does. In the piece, it came out that in the Beasties’ rowdier early years, Yauch had purchased a gun and had used it irresponsibly on a few occasions. Soon after, however, he had realized the error of his ways, and was horrified by the prospect of owning a weapon; instead of merely selling it to get rid of it, however, he destroyed the gun with a sledgehammer—he didn’t want anyone using it to hurt anyone. Furthermore, he put the gun-destroying episode on a Beastie Boys video collection; in doing so, he used his personal journey as a lesson for others to follow. I can’t think of a more powerful message, nor a more direct and visceral way to communicate it to people who actually need to hear it.

We don’t identify with our heroes because they simply act the right way all the time; from the saints to Siddhartha, it’s a journey of discovery along the path to righteousness, with a lot of major fuck ups and blunders along the way. Yauch put all those out there for us to see: we saw the struggle on his path to enlightenment, and that made it mean so much more. That allowed us to truly identify with Yauch’s journey, and cheer him when he finally reached the various summits along the way. In essence, his humanity in that process suggested that if we were to take on some of the tough questions and issues like he did, maybe we might learn something, too. He continually learned from his mistakes, and we learned right along with him.

In speaking with Yauch’s bandmates Mike Diamond and Adam Horovitz last year for an in-depth Q&A for Interview, I told them that I thought what would prove to be the Beasties’ lasting influence was, in fact, their efforts to raise consciousness. The Beasties’ music was revolutionary, no doubt, and remains timeless, no matter what era it hails from. But when they eventually came to terms with their early obnoxiousness and transcended it, it was a powerful message. Like artists spanning Minor Threat to U2 to Bikini Kill, they set an example—a code of moral ethics within which to exist, but in which there was a wide spectrum for creative expression. These artists don’t posit social consciousness as “cool”; it’s merely the way things should be. Beasties 2.0 were essentially saying, we can respect other human beings and still be ourselves—still be irreverent, still be countercultural, still be punk rock, but contribute to the betterment of the world at the same time. Once they put that down, the Beasties never deviated from that stance, and I always found Yauch to be the crucial voice in making clear the humanist element in everything they did. They stuck to their principles, and gradually their audience came around to realizing that knowledge is king after all—and the music would remain awesome, anyway. I can’t think of a greater legacy for a great person: Adam Yauch was brave to the end, as always, and that’s how I’ll remember him most.