Old-Time Memory Tapes

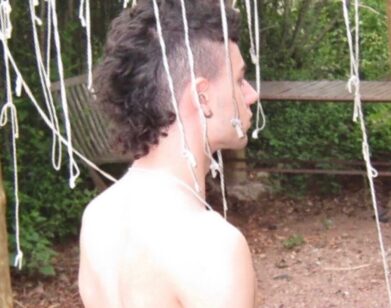

DAYVE HAWK, AKA MEMORY TAPES. PHOTO COURTESY OF MANUEL DOMINGUEZ, JR.

Distinguishing himself from his three musical aliases—Weird Tapes, Memory Cassette, and, most recently, Memory Tapes—Dayve Hawk (onetime frontman of Philadelphia band Hail Social) took some time to talk with Interview after the last rehearsal before his summer tour to promote his latest record, Player Piano (out July 5). Despite his reclusive reputation and his rural New Jersey home’s patchy phone reception, Hawk is a welcoming and contemplative raconteur. We probed the reasons why chillwave is a non-movement and how the nostalgic quality of his music makes Memory Tapes’ name perfectly a propos.

JAPP: You’re a self-described loner-type space cadet.

HAWK: That’s definitely me. I’m not a very social person. I’m interested in music and I’m obviously tight with my family—my daughter. I’m not at the club hanging out at night. I’m at home making records.

JAPP: Do you think it contributes to the nostalgia in your music?

HAWK: Yeah, definitely. I think there are basically two kinds of musicians: some are extroverted and some are introverted. I think extroverted musicians are more in the entertainer kind of camp, which is just as valid, but you’re going to be more apt to make music that is of the moment—whereas if you’re coming from a more introverted place, the music is going to end up being more about the past or more personal. It’s not going to be about the people in the room, per se.

JAPP: When I listened to the Memory Cassette EP, Call and Response, it made me strangely nostalgic for the ’70s and ’80s, and I wasn’t even alive then! Why do you think your music has that effect on people?

HAWK: [laughs] I don’t know, honestly, I was talking about this last night. I did a press junket in Australia—they were all talking about the nostalgic quality of my music. But what’s funny was that they were all different ages. They were all nostalgic for different eras of time. I was talking to an older journalist who was like, “This is like the ’70s,” and I was talking to a younger one who was like, “This is like the early ’90s.” I guess there’s just something in the music. I know that sonically there are definitely references, especially to the ’70s and the ’80s like you say, but I think there’s also something else about it.

JAPP: Do you ever feel nostalgic for times that you didn’t live through or experience?

HAWK: I’m definitely one of those people who feels that they were born in the wrong era. I don’t know if that’s nostalgia. I have a hard time relating to most current things. It’s funny because I get associated with nostalgia a lot, but I don’t hang out being like, “Man, if it were 1986… If only…!”

JAPP: The new album, Player Piano, is actually rather light, carefree, and in the moment. Were you conscious of that change?

HAWK: I made it almost immediately after the first one. I just wanted to do something else. The idea was that I always loved early pop music. Most of it is some of the most uplifting music you can hear, but it never sang anything particularly positive. I wanted to make a record where I would lyrically say nothing positive but have the music sound very optimistic, very sunny.

JAPP: It’s not really love-y. I don’t think I’ve ever heard you play a love song.

HAWK: [laughs] There’s no love. There’s just a lot of resentment. Just bad attitude. But that’s intentional, that’s what I like. I love the whole idea of Motown. Their idea was to sing how down on their luck they were, but the song implied hope that it would get better. I liked that idea, and I wanted to go even further with it.

JAPP: The Memory Cassette EP song titles are banal, like “Body in the Water” and “Asleep at a Party,” which is refreshing because a lot of music is so overdone with the artificial emotions. Your way is more genuine.

HAWK: That’s definitely where my interests lie. I like things that are contradictory or seem one way but are another way. I think it’s more genuine. It’s the way I am. I am very positive in certain ways and extremely negative in other ways. I think it’s most appropriate if I can write a super pop-y song singing about killing myself. [laughs]

JAPP: It’s funny because the music is so dance-y. Since you live the rural, rustic lifestyle, it doesn’t fit in the obvious sense.

HAWK: Right. I always tell people that I have never ever gone dancing in my life. But that’s the point. It’s the point of dreaming of doing it, imagining doing it. It’s like a fantasy version of it, not a practical version of it. With the way a club DJ would make a track—they are in the club, they know how to get people excited. I don’t know how to get people excited. I’m just imagining euphoria; I’m not necessarily feeling it.

JAPP: That’s how I see it working perfectly with the rural landscape. As a New Yorker, I idealize the countryside, because I think feelings like those I get from dance music would be the same as what I would feel in the country where I’m free.

HAWK: It definitely makes sense. The whole appeal of dance music is being liberated because music is liberating and it’s not about club culture or the social aspect of playing the mating game or whatever you’re doing at a club. It’s more about the euphoric aspect of listening to music.

JAPP: Do you feel that you could make the same kind of record if you were in a physically different place like Manhattan?

HAWK: I seriously doubt it. I’m sure it would affect my mentality. I’ve never lived like that. I lived in Philadelphia for one year, but I didn’t make any music during that year. I was basically like a mental patient. All my friends are from Philly, because it’s the closest city to me. They think I live in bumblefuck. I need the space. I need to be able to sit around with a bunch of trees and bugs.

JAPP: Do you ever have dance parties with your daughter?

HAWK: Of course! She loves dancing. That used to be how we put her to sleep for a while, because I think she inherited my inability to sleep at night. I used to actually play music and dance with her, and she’d eventually just pass out on the floor. [laughs] She doesn’t like lullabies. She likes Black Sabbath. I tried to play her soft music, and she said, “Daddy, this is boring.” The only music she’ll tolerate is the B-52s and Black Sabbath.

JAPP: I found it fascinating that you don’t listen to contemporary music. It’s pretty wild that you’re so on the pulse with what’s hot right now in the independent music scene.

HAWK: That’s always confused me, actually. I feel like an asshole. Most of the press I end up doing now asks, “Make a playlist for us… What are your top ten current bands?” I’m like, “I don’t even know one band!” It’s kind of awful. I would love to get more new music. I’m just not that amazing with the Internet and things.

JAPP: If you still manage to be on the same wavelength as other artists, do you think that music is organically evolving towards electronic music?

HAWK: Definitely. It seems that the Internet is setting the standard for almost everything. I can’t imagine having something like punk rock happen where an entire culture is doing one thing. It’s not like all the kids in England are discovering the Stooges and the Ramones at the same time. All the kids in England are discovering every band that has ever existed. I can’t imagine there being one huge cultural moment like there was in the past. Everything ends up being kind of postmodern. I think it’s silly when people try compartmentalize it. That was always my problem with the chillwave thing—people were trying to make it into some kind of musical movement, when it was not a movement. A couple dudes had a couple songs for a couple months. It’s going to be a disparate onslaught of people throwing ideas at the wall.

JAPP: What about you? What is the future for Memory Tapes?

HAWK: Throwing ideas at the wall.

MEMORY TAPES BEGINS AN INTERNATIONAL TOUR TODAY IN NEW YORK CITY, WHERE HE WILL PLAY AT MERCURY LOUNGE. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT HIS BLOG.