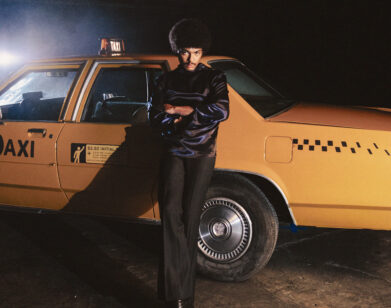

Kendrick Lamar

Putting a positive light on where I come from is important to me. When you think of Compton, there is this idea that it’s numb with negativity.

— Kendrick Lamar

Few hip-hop stars have arrived as fully formed as 25-year-old Kendrick Lamar. Hailing from the MC hotbed of Compton, Lamar has been cranking out increasingly adventurous mixtapes since he was a teen, at first under the name K.Dot (a moniker he later abandoned). But with the release last fall of his proper major-label debut, good kid, m.A.A.d. city (Interscope/ Aftermath/Top Dawg Entertainment), Lamar took his show widescreen. He subtitled the album A Short Film by Kendrick Lamar, and there is something palpably cinematic about it. It’s a deftly nuanced work filled with richly painted vignettes, complicated characters, and shifting perspectives that begins with a 17-year-old Lamar trying to find his way as he is being pulled in multiple directions by his friends, parents, hip-hop fantasies, girls, and the culture of Compton, and ends with him figuratively taking the baton from Dr. Dre while wondering if what he has achieved is a victory or simply part of a cycle. (Another Compton legend, MC Eiht, appears on the track “m.A.A.d. city.”)

On the back of the hit singles “Swimming Pools (Drank)” and “Poetic Justice,” good kid, m.A.A.d. city reached No. 1 on both the Billboard Rap and R&B/ Hip-Hop charts. This past March, Lamar was even anointed “Hottest MC in the Game” by a panel of experts empowered by an authority no less than MTV (formerly an acronym for “Music Television”).

Nevertheless, to reduce good kid, m.A.A.d. city to a pop phenomenon is to, in part, ignore the thrust of its instant-classicness: Like some of the best records in the history of pop, it’s an album that not only tells a compelling story, but a near-definitive one of a specific time and place, offering a window on the varying complexities of turn-of-the-century Compton, where the gangs, drugs, and guns are all still plentiful, but the kids now also have a generation of grade-A hip-hop to fall back on in struggling to navigate it. In fact, songs on good kid, m.A.A.d city like “The Art of Peer Pressure” deal directly with the glorification—and the growing urban mythology—of the rags-to-riches gangsta-rapper narrative that surrounded Lamar as a kid. But good kid, m.A.A.d city is also an intensely personal album that draws its power from Lamar’s frequently ambivalent—and conflicted—relationship with the people and world that he is chronicling. In one of several voicemail interludes that punctuate good kid, m.A.A.d city, Lamar’s mother offers him some advice: “Tell your story to these black and brown kids,” she urges. “Let them know you was just like them, but you still rose from that dark place of violence, becoming a positive person.” Near the end of the capper, “Compton,” the true complexity of that story is brought into full relief as Lamar slyly raps, “Harsh realities we in made our music translate / To the coke dealers, the hood rich, and the broke niggas that play . . . Roll that kush, crack that case, 10 bottles of rosé / This was brought to you by Dre . . . In the city of Compton / Ain’t no city quite like mine.”

Singer, songwriter, and fellow raconteur Erykah Badu recently caught up with Lamar by phone at the airport in Denver. Badu was at home in Dallas, Texas, and Lamar, who has seemingly been in constant motion while touring the world over the past year, was enjoying a rare unscheduled breather, having just missed his flight.

ERYKAH BADU: Can you describe how it feels to be in this cyclone of good fortune that you’re experiencing right now? How are you handling all of it?

KENDRICK LAMAR: I always thought money was something just to make me happy. But I’ve learned that I feel better being able to help my folks, ’cause we never had nothing. So just to see them excited about my career is more of a blessing than me actually having it for myself. My folks ain’t graduated from high school or nothing like that, so we always had to struggle in the family—and I come from a big family. But as far as me handling this, it’s a weird feeling because it’s like a blur right now. I think my worst problem is actually living in the moment and understanding everything that’s going on. I feel like I’m in my own bubble. People tell me all the time, “You’re crazy, going there by yourself,” because it wouldn’t have soaked in yet that I’m supposed to be quote “Kendrick Lamar”—whoever this guy’s supposed to be. I still feel like me. So it’s really about me trying to adapt—that’s like the toughest thing for me right now. I feel like I’m in my own world.

BADU: Is it a good world?

LAMAR: It’s got its pros and cons. I still know who I am and I haven’t let everything consume me. But on the other end, I have to know when I’m me—when I go out in public, to the person that sees me on TV and has a conception of who I am. That’s the only catch. That’s the flip side to it. But I think whatever pressure I feel all comes from me, from within. I always was that person who was hard on myself and challenged myself no matter what I was doing, whether it was passing third grade or playing basketball. I think it was a whole lot of pressure building up for this first album. But I looked at that kind of thing as excitement, you know? Since day one, since the first time I touched the pen, I wanted to be the best at what I do. So I’m just taking it one day at a time.

BADU: That’s great because it’s easy to get caught up in your own hype, if you will. You know, when you’re on Twitter or Facebook and there’s all of this praise—it’s easy to get caught up in all that.

LAMAR: That’s why I try my best to stay away from social media as much as possible. [laughs] When you go on your Twitter or look down your Timeline and it’s all great positivity—I love that. But at the same time, it can really divert you from what your purpose is or what you’re trying to do. And I’ve seen artists get caught up in that. I’ve seen some of my friends get caught in that. Whether you’re a small celebrity or a grand celebrity, it really triggers something in your brain, seeing all that stuff . . . So I’m real aware of it.

BADU: What are you trying to achieve as a musician, if anything at all?

LAMAR: Well, like I was saying, as a kid I was always fascinated knowing that I could be the best at something—like Jay-Z or Nas or B.I.G. But putting a positive light on where I come from is also important to me. When you think of Compton, it’s numb with negativity, even to this day. So the whole purpose of this first album was really to spark the idea of doing something different rather than doing a record that’s just about gang culture. That’s the ultimate thing I want to do in making music—to be able to inspire somebody else.

BADU: Speaking of Compton, tell me about how you grew up. You said that you come from a big family.

LAMAR: My mom’s got 14 brothers and sisters, my pop’s got 10. They started in Chicago and came to L.A. . . .Well, they actually came to Compton—just them two—in ’84, and then they had me in ’87. But they paved the way for all my uncles and aunties and my cousins—eventually everybody came out. At one particular time, in the early ’90s, we all stayed in the two black neighborhoods in Compton. So it was one of them things where it was like we were the neighborhood. So, as a kid, I was watching all of these things going on—parties, drinking, smoking, violence. But I was totally oblivious to it because I felt like it was just life. At the same time, I had birthdays and Christmas and holidays, which allowed me to actually be a kid. It gave me the ability to be a dreamer. That’s what separated me from all my homeboys—the fact that I didn’t get caught inside the reality. I was always dreaming about doing something else or going somewhere else.

BADU: Do you feel like you’re more satisfied with your work if it’s something that you feel you’ve created from scratch, or if it’s influenced by something that you love?

LAMAR: I love all of my influences, but to know that I had this concept for the album from the first idea all the way down to the intricate details, and to know that idea has now carried all the way to a place like London, where I can hear people singing those exact words back to me—that’s the ultimate high for me. There’s nothing like that. I always thought it would be about the money, but what really makes me happy is the fact that I can come up with something from scratch and then actually do it.

BADU: You called yourself “Compton’s human sacrifice” on m.A.A.d city. What have you done in your life to make you feel that way?

LAMAR: Probably one of the hardest things to do was to actually do something positive coming from that space. It was so easy for me to dabble in everything else that my homeboys was doing, just being in the middle of the fire. So I felt like that was the sacrifice—for me to come out of that and do something positive. The moment I made that decision to get in the studio and actually work and study the culture of hip-hop, then everything just started to open up and blossom for me.

BADU: The first time I saw you was on BET’s Cypher. I didn’t know who you were at that time, but you stood out. What do you think your secret weapon is as a lyricist? What do you think that “thing” is that makes you stand out?

LAMAR: Oh, man . . . That’s a good question. You know, I studied people I looked up to: Jay-Z, Nas, B.I.G., Pac . . . But early on, I didn’t really have my own sound. I had a passion for it, but me actually rapping the way they rapped is what got me into doing my own thing. I think me being that intricate and studying songs line for line—I probably spent more time listening to albums than writing songs. But I think that gave me all the tricks in terms of wordplay, from how I pronounced my words to the actual delivery. I’m very intricate about that stuff when I go into the studio—it has to sound the way I heard it in my head. So that’s probably one of the biggest things that separates me when I’m working in the studio—just how I hear certain things.

BADU: Is there an MC who influenced you or whose level of excellence you feel that you will never reach?

LAMAR: [laughs] That I feel I’ll never reach? I’ll have to say Jay or Eminem. Jay for sure—just off the simple fact of his longevity. That, to me, is probably one-in-a-million for rappers. A good career for a rapper is five or six years, so I think Jay still being relevant and having the skills he has—it’s really unmatched. I hope I get to that level and keep my work ethic up and strategically think of certain things. But there will probably only ever be one Jay. He’ll probably go down as the greatest to ever do it. Pac also could’ve had that, but due to his passing, we’ll never know if he’d have reached that.

BADU: Outside of hip-hop, what other kinds of music do you listen to?

LAMAR: Indie or alternative stuff. Sonnymoon and Quadrants are a couple of bands that really inspire me in terms of the melodics of things and certain tones and just what feels good. It takes me back to the type of music that I grew up on in my household. We played a lot of gangsta rap, but we also played a lot of oldies, and I think that mix is part of what inspires my sound. My pops and my mom started playing Marvin Gaye and the Isley Brothers and all these people, but at the same time, they always had Snoop on right behind it in the same mix.

BADU: What has it been like for you to get to meet someone like Dr. Dre or any of these other artists who you looked up to when you were a kid?

LAMAR: It’s weird . . .

BADU: In what way?

LAMAR: Well, I’ve got an extra-specific story about Dr. Dre. I saw him when I was 9 years old in Compton—him and Tupac. They were shooting the second “California Love” video. My pops had seen him and ran back to the house and got me, put me on his neck, and we stood there watching Dre and Pac in a Bentley. I’ll never forget this moment—it was probably about a year and some change before Pac died. So the moment I met Dre 15 years later, that’s what was playing in my head. He was talking to me, and the whole time I was like, I hear him, but I’m not listening, because all I could think about was that moment when I was a kid. [both laugh] It was tricky at first because right after that he said, “Go in the booth,” so I had to, in a split second, stop being a fan and get professional. That moment was make-or-break for me in my career, but I executed.

BADU: In the tradition of people like Slick Rick and André 3000, you’ve also been celebrated as a great storyteller. What, to you, is the most fundamental aspect of telling a story?

LAMAR: Being able to tell one from start to finish, and making that puzzle come together at the end. That’s the art for me.

BADU: Now I want to ask you some questions outside of music, if you don’t mind. What is love to you?

LAMAR: What is love? Love to me is god.

BADU: What is god?

LAMAR: God to me is love. [laughs] It’s the ruler of all things, whether it’s with a person or with music or with your TV. I feel like it’s this energy. God is energy, love is energy.

BADU: And what do you feel is the opposite of that?

LAMAR: The opposite of love? Vice. Temptation. The negative influences that we have. The bad energy that comes around us and makes us do certain things. To me, it’s always been a war between the two.

BADU: Okay, let me ask you this: How do you choose chicks from backstage?

LAMAR: How do I choose chicks from backstage?

BADU: Yeah, what is the protocol?

LAMAR: I try not to. [laughs] I’m too scared. Anybody who knows me knows that I’m probably the most scared person when it comes to that because I’m so caught up in the act of sex, of something going crazy, going out of my control. I’m too paranoid.

BADU: [laughs] So you just pass?

LAMAR: I’ve got to because I’ve seen a situation where it got totally out of hand, where something seemed so innocent, and now this person has got allegations on them. It spooked me. This was before my career really started, though—before any “Kendrick Lamar.” And that right there? It changed my whole perception about certain things. I’ll always keep that in the back of my head.

BADU: So who is your asshole-checker?

LAMAR: Who is my what?

BADU: Your asshole-checker—the person in your crew or your family who let’s you know if you’re being a asshole.

LAMAR: I have two, actually. [both laugh] But the main one is a friend of mine—a lady friend who has known me since high school. She has always been someone, since day one, who has said something whenever I’m an asshole, or also if I’m doin’ something positive—but more so when I’m out of my element.

BADU: If I had to give you any piece of advice as an artist, it would be this: Get yourself an asshole-checker. Because a lot of times we don’t know. We get so used to getting everything that we want.

LAMAR: Right, and while you have people who are actually fronting for your needs and wants, sometimes your needs and wants may not be right for you. The people around you are just trying to keep their jobs.

BADU: What’s your favorite cereal?

LAMAR: Fruity Pebbles. When people ask for my rider, they think I’m crazy: Fruity Pebbles, baked chicken, bottle of Hennessy, and some Polo socks.

BADU: For real? I need to ask for so much more!

LAMAR: [laughs] As an artist, you can have some crazy stuff on there. But when I go backstage, I like to put some fresh socks on. My grandma always told me, “You ain’t got to take a shower for four days, but put some fresh socks on and you’ll feel better about yourself.”

BADU: I heard that you like to sleep on the couch.

LAMAR: Yeah. People trip out because I still like to do that. I can sleep anywhere. I don’t need a grand-type spot. Give me a little corner. People are always like, “Is he drunk?” “Nah, he’s just sleeping.” [laughs]

BADU: Okay, top five rappers of all time. Who are they?

LAMAR: Oh, man.

BADU: I know, it’s hard. I can never answer that question either. They don’t have to be in order.

LAMAR: Okay . . . Give me Jay-Z.

BADU: Bam.

LAMAR: Give me Nas.

BADU: I’ll give you that.

LAMAR: Give me Tupac.

BADU: I might give you Pac. . .

LAMAR: Please give me Pac. Also give me Snoop.

BADU: Okay, that’s four.

LAMAR: And give me B.I.G.

BADU: I’ll give you B.I.G.

LAMAR: But that leaves off Eminem and André . . . I’d probably formulate the perfect 10 if I really thought about it for a day.

BADU: You just named seven. You got three more?

LAMAR: Rakim . . . [pauses] Kurupt.

BADU: That’s nine.

LAMAR: Who would the last one be? Give me Method Man.

BADU: I will give you Method Man all day.

LAMAR: But it’s a battle because if I say Method Man . . . Will you give me DMX?

BADU: Okay.

LAMAR: Yeah, give me X. That’s my 10.

BADU: And then Meth would be the alternate. I hope y’all get that into Interview magazine. [Lamar laughs] So what kind of whip do you have right now? What kind of car you pushin’?

LAMAR: A tour bus. [laughs] I’m humble.

BADU: You don’t have a house?

LAMAR: Nah, I live on the tour bus.

BADU: Seriously? You don’t have an apartment or a house anywhere? You just kind of roam the world?

LAMAR: Rolling stone . . .

BADU: Is this something you’ve chosen? Or do you feel like you’ve got plenty of time to root somewhere?

LAMAR: I don’t know . . . I think it’s just who I am. I’m comfortable with it until the time comes when I actually have to decide where to be.

BADU: So when you’re not on tour, where are you?

LAMAR: Probably in a hotel.

BADU: In Los Angeles?

LAMAR: Yeah. Or in the studio.

BADU: You sound like the typical Gemini. But let me ask you this—I’ve been here for 42 summers, and I still don’t get this: Despite everything that’s gone on, I feel like there is still a hierarchy of humanity, and women are still treated very much like second-class citizens.

LAMAR: Right.

BADU: You know, I’ve created a lot of my videos and directed or co-directed all of them. I write my own lyrics and co-write the music and do the concepts and collaborate on the artwork for my albums. Anything that has to do with my work, my hands are in it—and I’ve created it all out of my blood, sweat, and emotions. But I see that men, in some circumstances, can have this power to shut all of my dreams down at any time. So let me ask you: What do you, as a man, envy about what it means to be a woman?

LAMAR: There’s just a certain knowledge instilled in a woman. There are these things that women have that men just can’t grasp: the understanding of love; the understanding of being; having a certain type of care in your heart and knowing when to be compassionate; knowing how to be a confidante . . .

BADU: That’s a good perspective. Something I envy that men have is that ability to grow a goatee. I think that’d be really hot on me.

LAMAR: A goatee! [laughs]

BADU: A goatee with a hair wrap . . .

LAMAR: So let me ask you a question: Would you rather have been a man or a woman?

BADU: Because I have no memory of my past lives, I don’t know what it feels like to be a man. I think I would like to experience it, though. I mean, I’m happy that I am who I am, but being a woman in her forties ain’t no joke, man. I’m tellin’ you . . . This is some other-ness shit. There’s a hormone that gets released called “I don’t give a fuck”—it is heavy. [laughs] But I would love to experience being a guy. Would you ever let a girl paint your toenails, just for fun?

LAMAR: Paint my toenails for fun? I don’t know—I’d have to be in that type of moment . . . But I don’t think so. [laughs]

BADU: Even if she promised to take it off right afterwards? After she took a picture . . .

LAMAR: After she took the picture? No. She’s gonna leak the picture. [laughs]

BADU: Would you not do it because you’re afraid that it would give people the wrong idea about your sexuality? Or is it because you just don’t like those kinds of chemicals on your body?

LAMAR: I don’t think it has anything to do with worrying about how anyone would think about my sexuality—I just couldn’t see it, you know? That’s just me.

BADU: What if Jay-Z did it first?

LAMAR: Well, if Jay-Z did it first . . . I still probably wouldn’t.

ERYKAH BADU IS A FOUR-TIME GRAMMY AWARD-WINNING SINGER AND SONGWRITER.