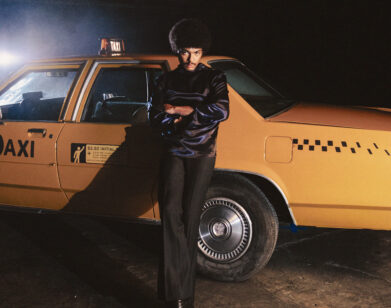

Kendrick Lamar by Dave Chappelle

Is it wickedness?

Is it weakness?

This couplet, which opens DAMN., the latest album from Kendrick Lamar, cuts right to the quick of the powerful anxiety that is so prevalent in all of his work: Am I strong enough spiritually? Physically? Is what I am doing right? Good?

These are universal concerns, of course, but acutely felt by one on whom such great expectations are placed. From early on, maybe even from the time of his first mixtape in 2004, when he was only 16, Lamar was a rapper with profound potential. After a series of star-making appearances on other artists’ songs, Lamar was, in 2011—even before the release of a proper major label album of his own—already being hailed as the best rapper on the West Coast. When it did arrive the next year on Dr. Dre’s Aftermath imprint at Interscope, good kid, m.A.A.d city only emboldened that opinion. In due course, the album went platinum and Lamar was nominated for seven Grammys while being vaulted out of his native Compton, California, to go on Kanye West’s Yeezus tour. GKMC also probably set in motion the endless comparisons of Lamar to Tupac, as well as the ongoing debate about whether he is the greatest rapper alive.

That’s a lot. But if it was Lamar’s soaring ambition and lyrical talent that made him particularly great, it is his honest introspection in verse and the clarity with which he has described his interior life that have made him sublime. His next album, 2015’s To Pimp a Butterfly, is nearly neurotic with its naked fears about losing out to the devil (or “Lucy,” as he called the evil that tempts him); about letting down his hometown; and about approaching escape—velocity fame and wealth, which might, as it did for Tupac, rocket Lamar out of reach from any sense of community, family, or belonging.

In signature fashion, the 30-year-old faced his fears head on. He came home and put Compton, the Coast, and everyone else on his back to make DAMN., a dazzling and utterly singular album that he says he recorded—and is presently touring—to bring comfort and strength to the rest of us. “LeBron James or the little boy around the corner,” Lamar tells Dave Chappelle, a comedian and cultural critic who knows a thing or two about greatness. “We come from the same struggles, and it comes out of my mouth for them to relate to.”

And if what does come out is, despite all of Lamar’s successes, still fraught with self-conscious anxiety, it seems to support the old truism popularly attributed to Bertrand Russell: “The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people”—or, we might say, the truly righteous and brave—”so full of doubts.”

DAVE CHAPPELLE: Kendrick.

KENDRICK LAMAR: Dave. What’s going on, brother?

CHAPPELLE: The last time I saw you was in Australia with J. Cole—you had just performed with Eminem. A lot’s happened since then.

LAMAR: Definitely. How you been?

CHAPPELLE: I’ve been great. I want to start by asking you about a recent scandal in the comedy world: Kathy Griffin and the picture of her holding Donald Trump’s decapitated head. My question for you is not about politics, but about the content in your work. In comedy right now, the issue is, “When does a comedian go too far?” And I imagine in hip-hop that’s been a long-standing debate—even when I was coming up, when Bill Clinton went after Sister Souljah. When you write, how much do you think about the repercussions of anything you might say?

LAMAR: When I look at comedy—at Richard Pryor, at you—it’s all self-expression. I apply that same method to my music. I came up listening to N.W.A and Snoop. Like them, it’s in me to express how I feel. You might like it or you might not, but I take that stand.

CHAPPELLE: I have this thing when I write jokes; I call it my unseen audience. I’ll think of certain people when I’m writing certain types of jokes. For instance: “What would my mother say?” Who do you think about when you write? Are you thinking about the streets? A lot of your work is openly spiritual and contemplative.

LAMAR: I really focus on what my fans will take from it, people living their day-to-day lives. At the end of the day, the music isn’t for me; it’s for people who are going through their struggles and want to relate to someone who feels the same way they do. I’ve got to take Mom out of the equation. I’ve got to go all-in, expressing myself, right there in the moment.

CHAPPELLE: What did you think when LeBron James, after an amazing, clutch performance [in a historic, 26-point comeback win during the playoffs], was like, “I just listened to DAMN. and got amped.”

LAMAR: Moments like that … If I hadn’t expressed myself in the studio, who’s to say he would have been listening to the album? LeBron James or the little boy around the corner, we come from the same struggles, and it comes out of my mouth for them to relate to.

CHAPPELLE: I know you’re a big Tupac fan. And Tupac used to talk about this phenomenon, as he got successful, that he was out of context. He’d say, “Where am I supposed to go? I can’t be around the ‘hood anymore, and they don’t want me in the Hollywood Hills. Where am I supposed to go?” Have you run into any altitude sickness from your ascent, fighting all the way up to where you are now?

LAMAR: I think I’m still growing. The more people I meet, the more cultures I start to embrace, the more people I open myself up to—it’s a growing process I’m excited about. But it’s also a challenge for me, to be at this level and still be able to connect with somebody who’s living that everyday life. At first it was something I struggled with, because everything was moving so fast. I didn’t know how to digest it. The best thing I did was go back to the city of Compton, to touch the people who I grew up with and tell them the stories of the people I met around the world. Making To Pimp a Butterfly was me navigating those experiences. I went to Africa and I was like, “This is something I can enjoy and something I can challenge myself with.”

CHAPPELLE: Was Africa your “Oh, shit, I made it” moment?

LAMAR: I went to South Africa—Durban, Cape Town, Johannesburg—and those were definitely the “I’ve arrived” shows. Outside of the money, the success, the accolades … This is a place that we, in urban communities, never dream of. We never dream of Africa. Like, “Damn, this is the motherland.” You feel it as soon as you touch down. That moment changed my whole perspective on how to convey my art.

CHAPPELLE: Me and Mos Def argue about this all the time. Mos is of the belief that a person with a platform has a responsibility to other people. It’s the old adage, “To whom much is given, much is expected.” I don’t necessarily agree with that. I think some people can make conscious records, and some people can make booty records, and other people can make whatever the fuck they want records. But what do you feel, personally, when you’re making a record? Do you have a mission statement? What, if anything, do you hope to accomplish with your platform?

LAMAR: As I’ve grown as an artist, I’ve learned that my mission statement is really self-expression. I don’t want anybody to classify my music. I want them to say, “This is somebody who’s recognizing his true feelings, his true emotions, ideas, thoughts, opinions, and views on the world, all on one record.” I want people to recognize that and to take it and apply it to their own lives. You know what I’m saying? The more and more I get out and talk to different people, I realize they appreciate that—me being unapologetic in whatever views and approach I have.

CHAPPELLE: That’s the way I like to do it, as well: go for broke. It feels better to just say it. Is “Duckworth” [a track on DAMN. in which Lamar narrates the story of his father, “Ducky,” preventing an armed robbery, as well as his own potential murder, at the KFC where he was then working to provide for Lamar] a true story?

LAMAR: True story, and one of my favorite records on the album.

CHAPPELLE: A profound story, too. I like the meditation of it.

LAMAR: The idea that I wanted to put across from that event was one of perspective. Everybody has their own perspective, and recognizing someone else’s perspective blows my mind a hundred thousand percent. The way that event unfolded … I had to sit down and ask my pops, “What was your perspective at the moment?” And, “Did you ever think it would come around full circle like that?” That always fascinated me.

CHAPPELLE: Is it strange to hear people interpret your lyrics, the depth that they find in your work? The week the album came out, all these kids were telling me about digging into the songs and picking out clues. I don’t think every artist is listened to that way.

LAMAR: Everybody has their own way of hearing songs. My fans are usually pretty on point. Sometimes they go all the way to the bottom of it. It’s fascinating to me how far an idea can go. I wrote most of my first album in my mom’s kitchen, and now I can go around the world and hear people recite those lyrics, and understand the story, even though they’re not from the same area I grew up in.

CHAPPELLE: How did you feel putting out the new album? Sometimes you put something out and you don’t know what it’s going to do. But other times—like a Steph Curry shot—it just feels good when the wrist snaps, and it’s like, “Oh, this shit’s going in.” Are you having fun?

LAMAR: Definitely. I’m enjoying that people aren’t only listening to the album, but hearing the album. To go on that stage and perform that record, that’s the most fun I have. I get a full party every night.

CHAPPELLE: Do you develop a lot of new material from touring?

LAMAR: It comes from everywhere. I think now it initially starts on tour. I like to talk to people; I don’t care if it’s a kid or an 80-year-old woman, I talk to people. Then I return to the studio and see what comes together at the end of the day—but it’s definitely a process.

CHAPPELLE: It seems like you maintain your relationships well, that you’re paying attention to them. Have the changes in your lifestyle made it harder to do that?

LAMAR: It will never be easy. There are so many people pulling at me at one time—some want the business, some want my love, some just want my support, just to be there or to acknowledge them the same way I used to. To be able to figure that out is an ongoing process, because there’s always another show, another album, another moment that I don’t want to miss. But I’m pacing myself. I hope the powers that be keep me on a straight course.

CHAPPELLE: From the outside looking in, you’re doing beautifully, man. Your work is great, and you seem grounded and centered and focused. When I was your age, I used to fuck up all the time. [laughs] Hopefully, I can catch one of your shows on the road. I’ve heard nothing but good things. As a matter of fact, the first time I heard about you was through Mos, who told me years ago, “You’ve got to watch this kid.”

LAMAR: Mos gave me a lot of game early on. A lot of game.

CHAPPELLE: He said to me that you’re the one. Turns out he was right.

DAVE CHAPELLE IS A COMEDIAN, ACTOR, WRITER, AND CO-CREATOR OF CHAPPELLE’S SHOW, WHICH AIRED FROM 2003 TO 2006. HIS STAND-UP SPECIALS THE AGE OF SPIN AND DEEP IN THE HEART OF TEXAS WERE RELEASED ON NEFTLIX EARLIER THIS YEAR.