DJ Discourse

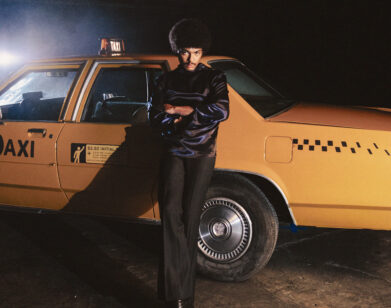

JONATHAN TOUBIN IN NEW YORK, JULY 2015. PHOTOS BY VICENTE MUÑOZ.

Known as a DJ, producer, writer, musician, and historian, Jonathan Toubin is a multihypenate in every sense of the word. Praised as “the most-liked man in the soul music scene” by Rolling Stone and “the only DJ we actually like” by Vice, Toubin fuses obscure rhythm and blues from the ’50s and ’60s, with rock ‘n’ roll and soul 45s. His ongoing New York Night Train parties easily draw those typically found sulking in corners of bars out onto the dance floor. The most recognizable edition of the party—New York Night Train Soul Clap and Dance-Off—features just what the name suggests: a mid-set dance contest.

The now 44-year-old (today, July 29, is his birthday) has performed around the world, sharing stages with the likes of Jack White and bringing the monthly Soul Clap to Australia and Europe. But in 2011, the morning after he arrived to play a show in Portland, a cab driver experienced a diabetic seizure, drove through the wall of Toubin’s hotel room, and landed on top of the musician. Immediately rushed to the hospital, Toubin nearly died, suffering from crushed lungs, 12 broken ribs, a smashed scapula, broken pelvis, several severed tendons, punctured spleen, damaged pancreas, and loss of hearing in his left ear. During his recovery process, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Gibby Haynes of Butthole Surfers, and Heavy Trash held a benefit concert at Brooklyn Bowl, where Toubin now frequently plays.

When released from rehab in January 2012, he thought his life as a DJ would most likely be over, although only one year later, he became the first person to DJ for the entire duration of Lincoln Center’s Midsummer’s Night Swing and the first DJ to receive a full showcase at SXSW. Soon thereafter he began his residency at Home Sweet Home (which he continues today), and began inviting guest DJs to share the booth, including musicians like Bob Bert from Sonic Youth.

Earlier this year, Toubin released Souvenirs of the Soul Clap Vol. 3 and Vol. 4—two compilations, each composed of 14 tracks that allow you to bring his party home, and tonight marks an outdoor edition of his Soul Clap and Dance-Off at Madison Square Park in New York. If you’re not in town, however, Toubin will also play every Saturday for the month of August, as part of Summer Thunder 2015. Near the release of Souvenirs, Toubin met with fellow musician Nick Waterhouse in Los Angeles. Waterhouse picked him up form the Omni Hotel and the pair spoke while driving around in search of tacos and horchata.

NICK WATERHOUSE: Jonathan, hey Jonathan! How you feeling?

JONATHAN TOUBIN: I’m a little raw. But that’s the right way to feel after one of those nights…

WATERHOUSE: Kind of wish I had some of those L.A. sunglasses.

TOUBIN: I have some prescription ones if you want to feel psychedelic this morning.

WATERHOUSE: Really weird. I counted 500 people or so last night. Did you get a door count?

TOUBIN: I think they said the total was over 500 or something people. The hammering though right now is loud. Also, you want anything? You want a taco? Horchata?

WATERHOUSE: I could do tacos. Do you have a taco stand that you like?

TOUBIN: There’s this one downtown I remember that’s pretty good. It’s kinda near Skid Row—it’s actually a restaurant but it’s like a taco stand. It just has a lot of salsas out.

WATERHOUSE: Oh yeah, it’s on 7th. I used to go there quite a bit. Last night I particularly enjoyed that you, as the emcee, wanted to reference Live at Budokan, in introducing the debut track off of the solo track compilation.

TOUBIN: “This is the first song of my new album.” I’ve been wanting to say that for a while. I’m glad someone got it.

WATERHOUSE: I think that really sums up how you bridge worlds in your career—what role you play is the bridge between Live at Budokan, and what track is it again?

TOUBIN: It’s “The Dances,” which isn’t even really a solo song. But to be honest, I was thinking I should approach those like I do parties, where the variation of what it is makes it multidimensional. I think one of the problems with the really categorical European-style compilation system is that all the songs are just specifically what it is. We both went to graduate school, where all you do is categorize things. When they asked me to do these, I was like, “I’m only making this, ’cause I’m playing my thing.” You have a personal compilation.

WATERHOUSE: I latch on to exactly the terminology you just used, which I would like to unpack—the European style of compiling. Do you think this is your own rebellion against a formalized structure?

TOUBIN: No, you know what’s funny, I wasn’t rebelling against these old soul parties or compilations or anything. I didn’t really keep up with that stuff much, and to be honest I just did what I thought would be cool. As I started finding out what other people do—and there’s this whole world that’s really strict—I just thought, “This doesn’t involve me much.”

WATERHOUSE: I was really turned off by the dogma of it as well. When your party arose, when I was becoming aware of nights, and nights specifically where you could be in any given city towards the end of the 1990s, it seemed almost like role playing: “This is a mod night,” “This is a northern soul night.” The vitality and genre breaking that I started to see from people like you was about returning to the real, unhinged nature—an erosion of boundaries between two types of records.

TOUBIN: That’s what DJing was until recently; it’s how you put records together with the mixer. The whole culture came out of that. I understand people with really expensive records don’t tend to like to mess with them very much because they don’t want to scratch them up. Often a record collector and DJ aren’t very similar, yet a record collector kind of needs a DJ to do something with the records, otherwise it’s like collecting stamps.

WATERHOUSE: You were saying to me last night that the contest itself becomes secondary to the party, but [the contest] baits this audience into feeling the ebb and flow, and they all want the dance party after the contest occurs. It’s like you’ve created the ultimate vaudevillian-like approach to making people reengage.

TOUBIN: Basically, I think any DJ that’s a real DJ has to think all the time about what things mean, how people feel, how they react, and when things need a little more energy or a little less. But good music, literature, anything—it’s all tension release that makes a night and there’s a narrative. What happened with this was, in New York we had this little joke dance contest. Once it started going, people started asking me to do it in other places. I thought people just wanted me to DJ, but then they’re like, “We want the dance contest.”

So I had to work a lot on trying to make the contest this intermission, but also this thing where people would watch the dancing to [the point] where they desire dancing themselves and, as a group of people, feel like they are participating in the spectacle. Instead of being in the dark and doing whatever they were doing before, it builds a community that has a shared experience. So when the lights go off and we have the dancing again, not only do you have that tension and that desire, but you also have people who know each other a little better and have shared something. They feel a little more comfortable, I think, than they normally would.

WATERHOUSE: You’re a true unifier; you introduce a panoply of counter cultural figures to each other. Like last night you introduced me to Don Bolles…

TOUBIN: The Germs, in my opinion, started the punk culture in L.A. Don has been there the whole time. Basically all my DJ’ing I was a punk DJ, and then I started playing dance parties. At these dance parties I realized I don’t really care for electro, contemporary dance music. I don’t like techno.

WATERHOUSE: What did you play last night that was your version of techno? It’s got the intro and the clap?

TOUBIN: Oh yeah, “Soul Dance No. 3,” [by Carl Holmes]. That one has the beat but that’s the crazy thing—what you start learning is that people, if they don’t know the song, they still respond to certain events from the night, they still make associations that give them an emotional response if you get the right ones with the right meaning to the right people at the right time.

WATERHOUSE: So that is what you latched onto when you recognized you were getting into dance culture?

TOUBIN: I started doing these dance parties, playing what I liked, like The Stooges, and nobody danced. I started kind of thinking about it, like, “Well, if I went to a dance party and walked into some random place, what would I like?” I thought, “I really like that old kinda rhythm and blues and soul with all the screaming and guitar solos.” It’s a lot of like rock ‘n’ roll and punk. It’s very immediate.

WATERHOUSE: I think immediacy is a good term. When I hear certain records, if I think of you—the immediacy of the record is what comes to mind.

TOUBIN: The dynamics and the speed and sort of steady forward proportion. It’s so hard to find that in records, and then as a DJ, it’s really hard to play those two-minute records in a way that it moves and fits together for hours—five hours sometimes. But I do think that overall, it just ended up being a cool thing for these people. These cultures, these people who were judges were part of the punk culture I was involved in…

WATERHOUSE: But you also involve artists, rock ‘n’ rollers, comedians—it’s beyond just this culture of rock ‘n’ roll. You’re a unifier of this subterranean type. You were talking about how this rhythm and blues is still kind of perceived as trash in the culture.

TOUBIN: Compared to say, jazz, yes.

WATERHOUSE: It’s not academicized. Even I find that dance music, some people write it esoterically; the way people write about electronic music made now can be very cerebral and intellectual, when it’s all based in the same feeling.

TOUBIN: But electro is also highly theoretical. A lot of the people that have written about it and made it since the very beginning—the roots of that stuff is all in super conceptual people like Genesis P-Orridge or Kraftwerk or Brian Eno. A lot of grant writers started playing that music in the ’80s and the ’90s and the next era, so there’s definitely an intellectualized form. To me, you have to intellectualize it to enjoy it. This other stuff is just so immediately likeable and impersonable, in a sense I feel people take it for granted. The other thing is that people don’t see often the art in it because it’s a two-minute song, it does have screaming…

WATERHOUSE: And it’s fairly visceral…

TOUBIN: Once you compare the kind of stuff I have been trying to find to 99 percent of rhythm and blues and soul records, you find most of them aren’t artful. Most of them don’t have weird harmony. Every time I hear a very generic record of a genre, I get really bored. Even for the stuff I play, so much of it just sounds like it’s either sort of a cartoon of someone, or some guy is trying to cash in on “Oh, Ray Charles did this, so I’m gonna do it.”

WATERHOUSE: Besides the flow and programming on the new volumes, are there standout songs? You told me you were really proud of the first two, but you really feel like volume three and four, you worked very hard.

TOUBIN: The compilation is different than the live thing because live, I get to play whatever I want. To be honest, the majority of the songs that I play, we wouldn’t be able to legally use—like it would take a year or two to get permission. For the last one, the guy was chasing down a Cajun guy that he had to find for one of the songs; he had to pay a mob dude for another song. It’s a big process.

The other thing is—I’m not as much involved in the compilation world and I don’t listen to them all that much, but I look ’em up on discogs and see if that song has been compiled—it’s so hard to find a song that nobody has compiled.

WATERHOUSE: It’s an arms race of who gets to it first.

TOUBIN: Yeah, so I decided to go ahead and do a little mix of both. A few of the tracks have been on this and that, but the majority of them have never been on one. By not putting these songs on something, just to show respect for some compilation from 1992 or whatever, it means that you’re denying that material a chance to reach people. My compilation, this is the stuff I play at my party; when you go home it sounds like the party, and I did everything to make it sound like 45s.

WATERHOUSE: And you were very involved in the mastering process.

TOUBIN: I mastered both of them with my friends, so it wouldn’t sound like a regular compilation, it wouldn’t be scrubbed. It would sound like a really loud 45 kicking through.

WATERHOUSE: And that’s the spirit of the Soul Clap.

[Waterhouse and Toubin stop for coffee while en route to the taco restaurant]

TOUBIN: That hotel we passed that still says “Cecil” on the side but had a different name, I stayed there when I was 18, in ’89 or ’90.

WATERHOUSE: I want to know all about this.

TOUBIN: I just ended up taking a bus from Berkeley. I was living in Austin. I was going around visiting my friends. I had some friends in L.A., but there wasn’t cell phones or anything. I got here and took out my phone list and started calling up my friends and no one answered. This hair metal girl from the bus was like, “There’s a hotel around the corner, it’s 15 dollars. Me and my boyfriend are going to stay there,” and it was Hotel Cecil. I went in there and there’s a towel deposit, a key deposit. The elevator didn’t work—I went up like 13 floors, 14 floors, something like that…

WATERHOUSE: Was it a lot of tenants? Was it like permanent residents?

TOUBIN: I don’t know what they were, but I ran out of cigarettes by the time I got up the stairs. There were so many crackheads and prostitutes. I ate at the diner downstairs. It was really creepy. I was really into it, but I was also really scared. People kept knocking on my door all night and it had a noir element because there was a street saxophone player.

WATERHOUSE: That was actually one of my favorite things about living on 9th and Broadway: there was a street sax player and I was facing the Orpheum, so I would get him on select nights.

TOUBIN: That was when people gave money to saxophone players and supported the street. Now they only give people money if they have a pan flute and traditional Peruvian attire.

WATERHOUSE: You’ve been living in Brooklyn for a long time, my friend.

TOUBIN: We don’t have the pan flute guys, but if you travel a lot they make their way around—all over Europe. Everywhere. I don’t think they have any people left in Peru anymore.

FOR MORE ON JONATHAN TOUBIN’S NEW YORK NIGHT TRAIN, CLICK HERE. STAY UP TO DATE WITH THE ARTIST VIA HIS TWITTER.