Chilly Gonzales, in Harmony

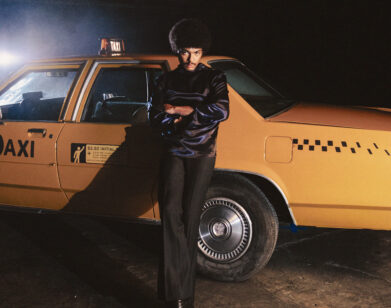

ABOVE: CHILLY GONZALES. IMAGE COURTESY OF ALEXANDRE ISARD

Attempting to pick one from among Chilly Gonzales’s many identities—pianist, rapper, entertainer, supervillain—distracts from enjoying his eccentricity in full. The 40-year-old, born Jason Beck, humbly suggests another take: “musical genius,” a half-joking honorific that is now being seriously considered by critical latecomers, much to the vindication of the performer and his fans.

While his résumé reads like total wish fulfillment—from producing indie chanteuse Feist’s debut album to playing before the BBC Symphony Orchestra in a satin bathrobe—the rakish savant demurs that he is “most famous for writing a song with three notes.”

“Can you believe that?,” he asks, the incredulity distinct even as he is says it by phone from Cologne, Germany, where he lives. The tune of dubious notoriety is “Never Stop,” a bright slice of piano pop that introduced Apple’s iPad to the world upon its 2010 release. Entering the public consciousness allowed Gonzales to stay consistent with his pursuit of being a “man of his time.”

With 2004’s Solo Piano, an album of brief hypnotism that is reactive and brooding, the Canadian pianist struck upon his own private language. Eight years later, the release of Solo Piano II finds him mastering it, and stacking new modern indulgences—tragicomedy as a musical device, the wonderful intoxication of melody, superhuman technical abilities—on top of one another in a way that’s as complicated and singular as the man rapping, improvising, and entertaining at the grand piano before you.

SHONA SANZGIRI: I saw you crowdsurfing at your show at the Barbican in London last week with the BBC Symphony. Can you describe what that experience is like, playing in such a venerable place?

CHILLY GONZALES: I do a hell of a lot of talking, as well. Sometimes I do things to just focus on the music and the intensity of it. At other times I feel a need to make it verbal and shocking, and to transgress, and to point out the ridiculousness of certain rules—as is the case with crowdsurfing at the Barbican. To do that is not inherently crazy, nor is it crazy to play at that hall, but to do it there is to point out the ridiculousness of acting in certain ways.

To me, a performance is a military operation; it requires so much planning, and then ripping up the plan the minute you get there because you have no idea what the audience is feeling. I’m very much an entertainer, and sensitive to the audience’s perception of me. I often have to do unexpected things, even for myself. I played in LA at the Mondrian Hotel, and I had a whole lot of people who were not even curiosity seekers and were there for something else. And I had to browbeat them so that the people who were interested would pay attention, and those who weren’t, would leave.

I did it to show that I was brought up in a very European way, musically speaking, by my grandfather, who taught me respect for the orchestra and the traditions and basically that Richard Wagner was God, and this was coming from a Hungarian Jew. And I was watching MTV in Canada, which is called Much Music, where I was brought up thinking Michael Jackson was God. This is a way for me to square that circle, to have the orchestra pump out those tunes. Taking yesterday’s skills and bringing them into today, kicking and screaming.

SANZGIRI: You’ve said that Europe embraces you in a way that North America does not—how so?

GONZALES: I left Canada because I was frustrated, because my way of using humor in music as a counterbalance to extreme musical depth was not welcome. There was a weird middle I was not interested in. When I left Europe, suddenly there seemed to be a very strong reaction.

It might have something to do with being first-generation European; my parents having escaped Europe, and I’m back, 50 years later, essentially doing European music, to their ears, as being part of a conservative classic tradition. And yet I’m doing it in a way that’s not done in Europe—the rapper’s attitude, the capitalist revenge fantasy. That part hasn’t taken hold in Europe, so I think it’s very exotic for them. Maybe just that rapper’s attitude as applied to their tradition is enough to titillate them in some way. The rapper’s attitude is everywhere in America, from the election to reality TV, so that’s not that exotic in that regard. The common attitude in music is not working for me.

SANZGIRI: I know you’re a big fan of hip-hop, before you were even a fan of the music itself—particularly the ambition of hip-hop spoke to you. What about it?

GONZALES: Rappers reminded me of my dad, who had the hustler’s mentality. I grew up with competition and success, like a religious aspect. I grew up with ambition, like some Catholics. I haven’t made my peace with it. The point is that like a Catholic, you can run away from it, you can run toward it, but it’s there and you’re reacting to it. I guess that’s what’s happening to me is about this gospel of ambition that I grew up with. I haven’t embraced it to the point that I did the same job as my father and took over his corporation. I’m doing it in an indirect way and on my terms. I could have also written music for commercials my whole life and probably approached more of what my father does. Oh my goodness, my dad is literally calling me on the phone. [laughs]

SANZGIRI: It’s a sign.

GONZALES: Right. The world I’m mostly in—some electronic, indie rock, underground world—it’s especially a bit of a taboo to talk about ambition. And yet many of my cohorts in that world, whether they’re DJs or singers, they’re wrestling with a lot of these same issues.

SANZGIRI: I’m a bit curious about your working relationship with someone like Drake—how do you merge the “Planet Gonzales” identity with someone who’s larger than life like that?

GONZALES: I think he was able to hone in on what is the true essence of what I do. He didn’t ask me to rap, to make beats, to write melodies with him. What he asked me to do was inspire him with harmony. And harmony is the third element of music, after melody and rhythm, and also the one which requires the most study to actually master. People can be very instinctive and extremely gifted melodically and rhythmically, and harmony can still be difficult.

By “being a musical genius,” what I mean is: being a mathematical genius doesn’t do you any favors as far as having something to say in music. You see every style as equal, and you want complicated music to devour. It took me much longer than other people who happened upon their tastes quite sooner. Someone like Peaches really got to the Peaches sound very early on, and I was jealous of that. It took me longer because I realized harmony was my way of having something to say. If people look at my work, they’ll recognize harmony.

SANZGIRI: Regarding the time when you were looking for your sound—I read about a period in your life when you “lost your musical illusions.” Which illusions?

GONZALES: I wanted to believe you could do it for yourself and have people like it as a bonus. That mostly went out the window, but it was such gospel that I was tempted to pretend that’s what I believed, even though I was deeply ambitious and wanted to treat it with a dose of humor. I didn’t have the balls. I was pretending to be something I wasn’t. That’s why I left. And when I went to Europe in ’98, I decided to wear it on my sleeve—these elements from rap music. Even if I wasn’t making rap music, I was going to approach it as a rapper.

But again, without the piano, I would never have attempted to rap, because I’m a poor rapper. I’m enthusiastic, but it takes me a long time to write eight bars of rap. I would battle any pianist, and yet I would forfeit happily before even getting into a rap battle with anyone.

SANZGIRI: I’m curious to know how living in Europe has affected you. You strike me as someone who would spend 12 hours indoor playing the piano.

GONZALES: You’re pretty close.

SANZGIRI: So I’m wondering how living there aids you in playing the music, if you’re basically bound to your instrument.

GONZALES: It gave me an audience, something to build on. It was such an immense relief, both personally and professionally, to feel like people were responding to a more complete picture with the Chilly Gonzales stuff. It was encouraging. I felt that in Canada, nobody cared. And I realized why.

Something about it was also so positive, like, “I’m never fucking going back to Canada! Revenge!” And that softened over time. The blame isn’t on the place I left. The blame is on me and recognizing that I needed to leave. I don’t feel like I’ve gotten revenge on all the people who underestimated me. That went out the window pretty quickly. Now it’s about finding the way to present my contradictions, art versus entertainment, which is the story of Europe and America. Europeans invented art for the last 300 years, and the Americans kind of killed it with a big, huge rock.

What it gave me was my first audience, and I think everything I do is fundamentally building on that original audience. It’s so important to me what this generation—a younger, more underground, I’m not gonna use the hackneyed term of “hipster”—but that’s the audience I care about the most.

SANZGIRI: I want to talk about the role of subversion in your music. You’ve referenced Andy Kaufman’s influence in the performative aspect of a Chilly Gonzales show. What about Andy Kaufman is important today?

GONZALES: What I like about Andy Kaufman was that his subversion was about observing the rules a bit too closely—what I call “over-orthodoxy.” If you’re going to point out the ridiculousness of a rule, it’s naïve to think that you can break it. It’s the same way that rappers have embraced capitalism. Some people say they liked it better when rap was a literal protest form in the ’90s. But I think it’s more a form of protest today, because it’s telling the story of what happens once something forbidden is within reach. I think rap is more political today when it speaks about luxury watches than it does about fighting the power.

I think those are the times we live in, that we get the rap we deserve. That’s a bit of a Kaufman-esque way to point out the rules and how an entertainer is supposed to be. What does it mean to be a positive, ingratiating entertainer? What does it mean to be a competitive motherfucker? I’m trying to apply that to the music world. He was one of the first people to point out the inordinate power of celebrity. A lot of these things that are still so fascinating to me, about what’s real and what isn’t, what’s onstage and what isn’t—we’re fascinated by the people where we can’t tell where one ends and one begins.

SANZGIRI: It reminds me of the playwright Ionesco and his idea that each of two contrary figures contain the other’s identity.

GONZALES: That’s why I think you never have to choose—you never have to choose between being the pure artist or the craven, sellout entertainer. You can be both. Rap borrowed so much from what Andy Kaufman was getting at, and bringing it to the fore—the self-contained contradiction, as you say. The better performers are doing this. Whether it’s Daft Punk, making emotionally affective music as robots, being faceless while being extremely media-savvy. This is an extension from the Andy Kaufman playbook, as it is for most rappers in their inclusion of the most base instincts and horrible aspects of humanity along an essentially positive message.

Andy Kaufman was not a subversive comedian in the way most comedians would think. He did most of it without ever uttering a swear word, or ever truly offending an audience. A lot of comedians today have misunderstood the concept of a subversive comedian. If you really want to be subversive, you have to please and offend in equal amounts.

SOLO PIANO II IS OUT NOW. CHILLY GONZALES IS CURRENTLY ON TOUR AND WILL PLAY THE BOOTLEG THEATER IN LOS ANGELES ON SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 3. FOR MORE ON THE ARTIST, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.