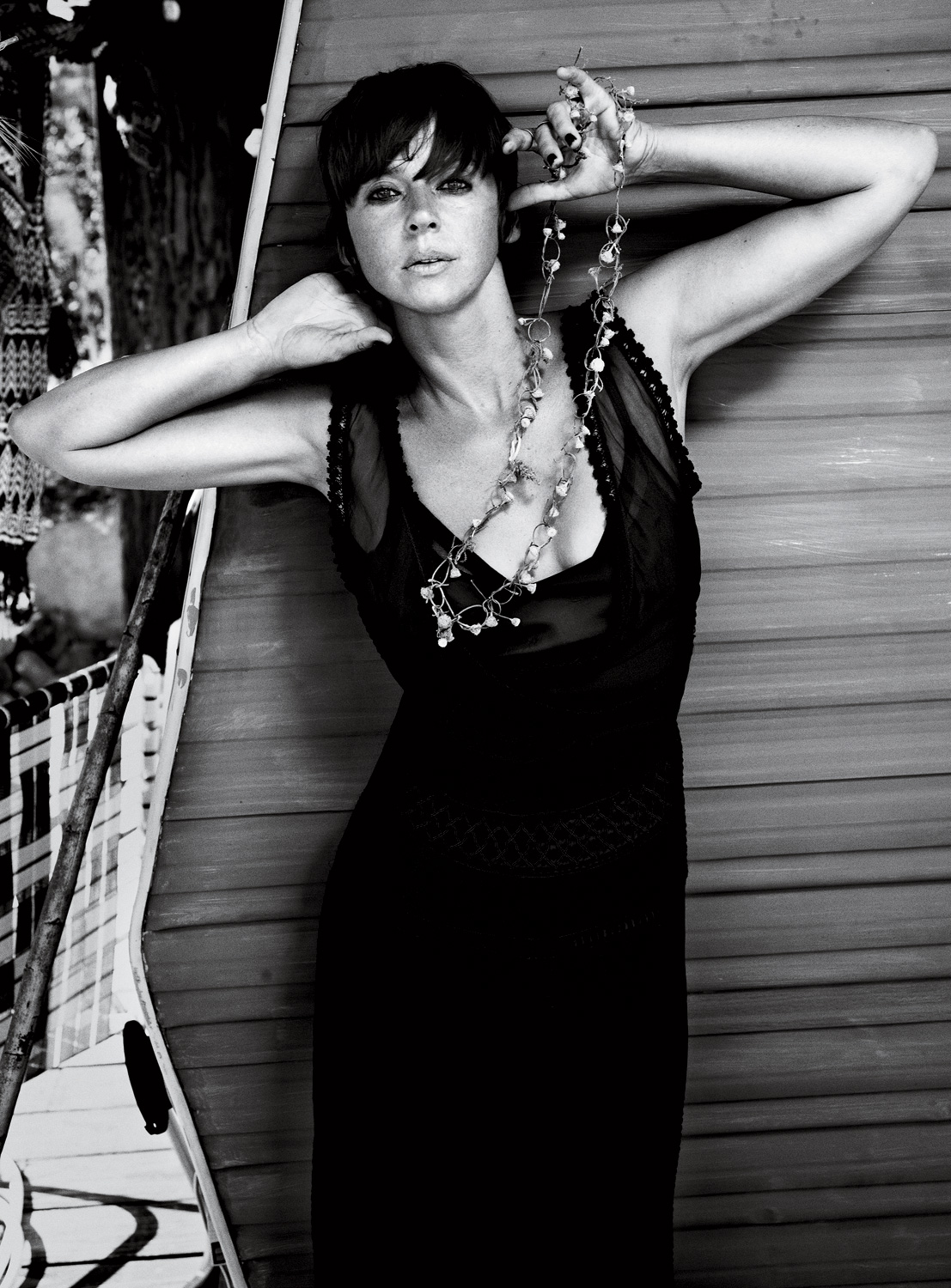

Cat Power

I MISS MY FRIENDS, SO MANY OF WHOM CAME TO NEW YORK FOR THE SAME REASONS I CAME HERE, WHICH WAS NOT TO WORK ON WALL STREETChan Marshall

If there really is such a thing as a true “indie-rock” rock star, then Chan Marshall—the mercurial singer-songwriter known as Cat Power—is it. Born in Atlanta, Marshall first emerged with her debut album, Dear Sir (1995), during the golden age of the mid- ’90s Alternative Nation, her minimalist compositions as emotionally harrowing as they were beautiful. She quickly became the unwitting fantasy object for both rock critics and music fans obsessed with the hypnotic and often inscrutable nature of her work. (She is one of the few vocalists who can tease abject heartbreak from a line as cryptic as “Yellow hair / you are such a funny bear.”) But the release of The Covers Record in 2000 propelled Marshall into a more mainstream arena. Her penchant for reinterpreting other people’s songs (her wholly irreverent take on the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” is already a classic) placed her in the rarefied territory of a Nina Simone, or even a Bob Dylan, two artists whose songs she has often sung, and whose own storied—and sometimes troubled—careers occasionally mirrored her own. Her infamously erratic live shows—characterized by rambling interludes, breakdowns, and a predilection for stopping midsong—reflected her battles with a variety of personal issues, anxieties, and addictions. As a result, the perceived image of Marshall as a fragile, unpredictable troubadour is one that has followed her for years. It wasn’t until the creative and commercial watershed of 2006’s The Greatest— Marshall’s take on Memphis soul music—that she finally began to shake the past. Having spent so many years seemingly hiding in plain sight, performing in front of countless audiences but still somehow lost in her own private reverie, this new version of Cat Power stepped to the front of the stage—abetted by some of the finest blues players in the world—and bloomed.

This fall, Marshall will release the first Cat Power album of original material in more than six years. On the aptly titled Sun (Matador), she turns yet another corner with a record that is a carnival of synthesizers, programmed beats, looping guitars, and live drums—all of which Marshall played and recorded herself. Having spent the past few years touring with accomplished backing bands—a scenario that allowed her to put down her guitar and focus purely on singing—Marshall was eager to flex all of her musical muscles, teaching herself how to create beats and play a variety of vintage synths. The resulting album, which she recorded in fits and starts at studios in Los Angeles, Miami, and Paris over the past three years, is arguably the most complex (not to mention patently optimistic) of her career.

T. Cole Rachel met up with the 40-year-old Marshall at the Bowery Hotel in New York City for a late brunch and endless glasses of iced tea.

T. COLE RACHEL: I know you recorded this new record in several cities. How was it different from the ways you’ve worked before?

CHAN MARSHALL: So many ways. In the past I might just write my songs by recording myself on a little tape recorder. I’d usually record things in a couple of takes—sometimes I’d just do it again if someone farted or I accidentally fell off the piano bench or something. This time, I wanted to work in real studios and work like a professional. I was recording in L.A. and Malibu and one of the assistants at the studio says, “You know, we have all these other synthesizers in the back. We have a RXZWZZZZ . . . whatever . . . You want to try that?” And I’m like, “Yeah, let’s try that out.” That was when the real sound of this record started to take shape. I didn’t have any idea how to play a lot of these things. You know, I’m like, “Push this button, make this sound . . . Okay, let’s try it again. Push a different button, make a different sound . . .” It took a long time.

RACHEL: Has making a record where you play every single instrument been on your mind for a while?

MARSHALL: Oh, yeah.

I HATE IT WHEN PEOPLE COMPLAIN ABOUT ME DOING SO MANY COVERS. IT’S PART OF A TRADITION. IT’S A PART OF THE CRAFT.Chan Marshall

RACHEL: You just felt like you couldn’t do it before?

MARSHALL: It was that thing where you’re surrounded by people who keep telling you, “You have such a great voice, you should just sing . . .” Or it’s the opposite, where you’re around people who say things like, “You should play more instruments,” and your default reaction is, “Oh, no. I don’t actually know how to play. I couldn’t possibly . . .” And then you start to believe that. I felt like I didn’t have the resources before. I wasn’t convinced.

RACHEL: On your last few tours, you’ve worked with two excellent backing bands, an experience that allowed you just to sing. How did that experience change you?

MARSHALL: I lost my mind from having so much fun. It was almost too liberating.

RACHEL: Perhaps, but it was also pretty transformative too, right? When you performed back in the early 2000s, you often seemed so uncomfortable on stage. But I saw you play just a few months ago and I almost felt like I was watching a completely different person.

MARSHALL: Oh, yeah. I see what you’re saying. Being able to just sing—just singing—totally changed me. And having those musicians backing me really helped because those guys are my friends. And for the first time I could perform without feeling like I had to be of two minds. When I perform alone, I often feel like there’s this need. In order to create the song as it exists in my mind, I have to be mathematical—the mathematical part on one side of my brain that plays the song in the right tempo, doesn’t fuck up the notes. And then there is the other part of the song— the other side of my brain—the spiritual, animal, beautiful part of performing that has nothing to do with math and everything to do with feeling. It can be difficult to get into a meditative state and really be there in the moment when you’re trying to balance those two things . . . especially when there are people watching you. With the band, I felt supported. I felt like I had their respect as people, as friends. I’d never felt like I had that before. When I was in my twenties, I never had that. The guys in the band were holding me up out there, you know? I felt protected for the first time, which is really important for a woman like me . . . I almost said, “for a girl like me,” but I’m 40 years old now. I’m a woman.

RACHEL: Your transformation as a performer has been such a cool thing to witness. When I see you play now, it actually seems like you’re having fun. There’s a joy in it. Before, seeing you play live was so nerve-wracking. I remember seeing you at the Knitting Factory in almost complete darkness—just you and a piano—and you would play these beautiful snippets of songs with these long passages of silence in between. No one was sure whether the show was over or not. There was almost a performance- art aspect to the whole thing, except you clearly seemed terrified. People in the audience kept shouting things like, “I love you, keep going!” which made it even more uncomfortable.

MARSHALL: There was always a lot on my mind. You’re hoping and praying that you and the audience can meet at the same place, some place that’s not here nor there but some “other” place altogether. It’s real scary when you’re out there by yourself. I wasn’t in a good place.

RACHEL: I love that you get to indulge all of these different creative impulses on Sun. A lot of people might not know about the sort of experimental, punk-rock origins of Cat Power—or that you can play drums.

MARSHALL: Well, I can’t really play drums or synthesizers, and I don’t really know how to take a beat and cut it up and drop it into a song or duplicate it into a computer program. I tried my hardest.

RACHEL: You’ve lived all over the place since you left New York about a decade ago. Where did you record this album?

MARSHALL: Well, let’s see . . . I recorded for several months at a studio in L.A. called The Boat, then I rented a house in Malibu and built a studio there. I wanted a place where other musicians could come and we’d all have a room—including myself—and space to work. I basically spent every dime I had saved on that place. I was doing tours intermittently during that time, and we would play some of the new songs, but it still wasn’t what I had in mind. I wasn’t sure how to get the sounds I wanted yet. Meanwhile, I’m touring to make money, and I’m in a relationship that is starting and stopping and starting and stopping. The record still isn’t sounding right. Long story, but I end up playing in Paris and I wind up working in a studio there called Motorbass. I also recorded in Miami at South Beach Studios and worked with some amazing people there . . . You know, it’s hard, and often I don’t get a lot of stuff done because we end up just talking about UFOs and spirits and shit like that. You know, it just takes a long time.

RACHEL: We’ve known each other for almost a decade.

MARSHALL: You shouldn’t say that, it makes us sound so old!

RACHEL: Well, we met when we were both 12 years old, here in the East Village . . .

MARSHALL: Oh, that’s right. I can finally go to a gay bar now and not get carded.

RACHEL: When it comes to talking about making music—specifically, your process for writing songs—you’ve always played that pretty close to the vest. I can probably count on one hand the number of times we’ve really talked about that stuff.

MARSHALL: It’s true.

RACHEL: I just got the feeling that it was something you desperately didn’t want to talk about. Your process seemed very mysterious.

MARSHALL: You are so sweet. It’s usually the first question people ask. Isn’t that what they always ask Bob Dylan? “How do you write them songs?” And he’s like, [Dylan voice] “I don’t know, man. It just happens . . .”

RACHEL: Your process for this record was obviously very different, but has your way of writing songs—for thinking about songs—changed much over the years? The only thing I can liken it to would be writing poems, which often feels like reinventing the wheel every time I do it.

MARSHALL: That’s a fucking good question, and something interesting I haven’t really thought about. So much of the time it’s just like, I really don’t want to be here. The basketball game is on. I just want to buy a bag of Oreos and get into bed. When I start writing, it’s like you have a hammer in one hand and a homing device in the other, and then it’s like, Now what do I do? And then it’s like, Well, I have to fucking do something . . . And then you start. That’s how a lot of the digital music on Sun got started—me just sitting at a machine and thinking, I might as well fucking press this button and see what happens. Lyrically, I usually work at a piano and just try and get into a kind of trance and play a part over and over and wait for something to come to me. Come, come, come, come, come . . . And then when it does, you just repeat it over and over until someone hands you a pen and you can write it down.

RACHEL: There’s a beautiful song on the record called “Manhattan.” You haven’t lived here in a long time, but the place obviously still weighs heavy on your mind.

MARSHALL: Oh, well, there’s this beautiful Langston Hughes poem about the Statue of Liberty—or that mentions the Statue of Liberty. I’d had this song in my head for a long time. It’s basically my homage to him, and to this weird idea of what liberty actually is. I kept thinking about the man in Manhattan, and the history of that word. People need to be reminded sometimes about what real liberty means—the idea that you can do whatever the fuck you want. And so much of the time people think they’re doing that, but really they’re just chasing money, not freedom.

RACHEL: My mind immediately latches on to some romantic notion of what the city represents, though the song suggests that most people come here for the wrong reasons now. The city has changed. Still, as someone who came here from a farm in the West—much like you came here from the South—I have to cling to the notion of the city as some place people can run away to in order to really become themselves.

MARSHALL: Everybody needs to get out of somewhere. Lots of people don’t though. Some people don’t want to leave their cubicle on the farm. I’m not trying to be mean to Manhattan, though. There’s always gonna be something about this city, something that when you are here and you look up and see the moon, the most natural thing in the world, it makes everyone the same. Like, it reminds me of when I was little. If there was a full moon, my grandmother would get me and my sister out of bed and we’d go sit outside in our nightgowns. She’d have a scotch glass with a little Johnnie Walker Red and some of those ice cubes that look like little half moons—you know, they come out of an ice machine and they almost look like little ribs of ice—and her cigs. And me and my sister would run around and dance with the dew on the grass. When I was in the fifth grade, my mom did the same thing—woke us up so we could go outside and howl at the full moon. There’s a line in the song about that as well . . . “Howlin’ to get me / howlin’ to get you . . .”

RACHEL: Do you miss New York?

MARSHALL: Mm-hmm . . . Yes, because I miss my friends, so many of whom came to New York for the same reasons I came here, which was not to work on Wall Street.

RACHEL: Despite your Southernness, I always think of you as being a New Yorker. Maybe it’s because of the culture that you sprang out of—the whole early-’90s Matador Records indie-rock thing.

MARSHALL: That was my school. That was my college. Those were my college years on the Lower East Side.

RACHEL: Having spent the past few years in between Miami and New York and Los Angeles—or touring—where do you think of as your home?

MARSHALL: Hmmm . . . Do you ever watch the show Ancient Aliens?

RACHEL: [laughs] Yes! My boyfriend’s sister is obsessed with it.

MARSHALL: Tell her to google “Chinese Alien Wars.” That’s all. Just start working on that. And then YouTube “NYC UFO sightings” and then count how many there have been in the past year compared to five years ago. I’m convinced! So blood type A—my blood type—is one of the most prevalent in the world, and you can trace it all the way back to the ancient Egyptians. It’s very old blood. Where did the new blood come from? Aliens. In Ancient Aliens, they explain how these visitors—these dragons in the sky—came down and helped create civilization. How the “angel” descended on Mary and got her pregnant— maybe an alien?—and then left. All the stuff that connects the Egyptians—who had the obsession with the elongated head— to a tribe in South America who were also doing the elongatedhead thing. How far away are those two cultures? It’s something to think about. So, where do I live? Where is my home? [laughs] That’s my answer. I’m convinced none of us are really from here.

RACHEL: You’ve always struck me as one of those people who seemed to suffer from touring inertia—that thing where you’re constantly on tour but can only talk about wanting to be home and have time off, but when you’re at home for more than a day or two, it’s all about, “I gotta get out of here!” For some people, once that movement has been set in motion, it’s a lifelong thing.

MARSHALL: It’s that need to do what you know. Yeah, I used to think I had that because I moved around so much as a kid. Different homes, different family members, constant back and forth . . .

RACHEL: I noticed another thing that changed after you started touring for The Greatest was—

MARSHALL: The fact that I wore a dress?

RACHEL: Besides that. After people could see you in that context—playing with this huge band, really expanding your singing style—you were suddenly talked about in the context of being a soul singer.

MARSHALL: “Soulternative.”

RACHEL: How do you feel about being thought of that way, as a modern-day soul singer?

MARSHALL: It’s embarrassing, because that happens to be my favorite kind of music and my favorite thing to hear. It seems too presumptuous somehow to call myself that. But still, you could be a classical musician from the 17th century or whatever and still have soul. My earliest roots are in soul music. My grandmother would take me to church—because that’s what you do in Georgia—and when you go to Baptist church, the fun part is that you sing. Those hymns are all so meditative to me—“I’m gonna lay my burdens down . . .” It’s all about giving. Not giving up, necessarily, but surrendering. It’s so rewarding, that kind of soul music, because it’s so . . . good. It’s just good. So when I think about it that way, I don’t mind being called a soul singer. I’ll happily accept that compliment, even if I don’t feel I deserve it or if it feels corny somehow.

RACHEL: I love that you have always been so involved in the tradition of interpreting songs. I don’t mean doing cover songs in the crass way that people often think of it now, but actually creating your own interpretation of a song, which is such a noble tradition in music. Why has that always been so important to you?

MARSHALL: The idea of doing a cover song today is usually about novelty or some marketing gimmick. But actually interpreting songs—that’s part of the thread work of the history of music. It’s tradition. When people complain about hip-hop— “Oh, they just copy someone else and it’s the same thing over and over . . .” No, it’s the same shit that we’ve been doing since people first started making songs, whether it be country or jazz or whatever. Everybody has always sung everybody else’s songs. It’s about the song. I don’t care if someone else wants to sing my damned songs. You know, if Bob Dylan hadn’t covered “The Moonshiner,” I would never have heard it or played it. If Eric Burdon hadn’t covered “House of the Rising Sun,” I wouldn’t have ever discovered it or probably have ever sought out the Dylan version. So I hate it when people complain about me doing so many covers. It’s part of a tradition. It’s a part of the craft.

RACHEL: Given the nature of your work, people often have this very emotional attachment to both the songs and to you as a person. I would guess people would like to always imagine you as this sad, fragile—

MARSHALL: Fuck-up—train wreck . . .

RACHEL: When people are so invested in thinking of you in that way—and, in a weird way, kind of want you to be that way—it must be a weird thing to have that sort of identity follow you through your career.

MARSHALL: Yeah, I understand what you’re saying. But, you know, I really did suffer for many years, so I know where all of that comes from. I totally understand it. But, you know, this life is a huge blessing. I’m so glad I came through all that.

RACHEL: Your record comes out in September. What do you want to happen next?

MARSHALL: I want to go on tour. I just keep imagining this big hill and I’m going to climb it. I’d also like to do a remix record with some of the songs from Sun. And I’d also like to make a new record, sooner rather than later. I just want to be happy and healthy and do a good job.

T. COLE RACHEL IS A FREQUENT CONTRIBUTOR TO INTERVIEW.