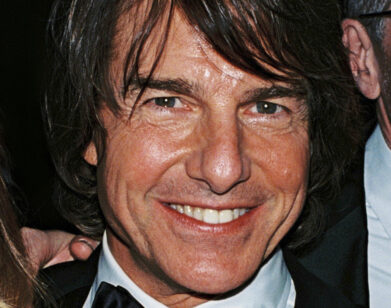

New Again: Steven Spielberg

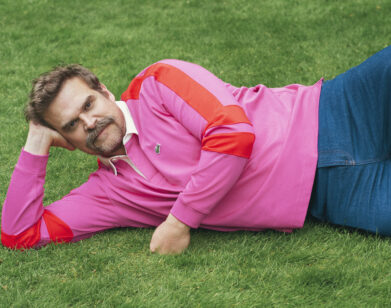

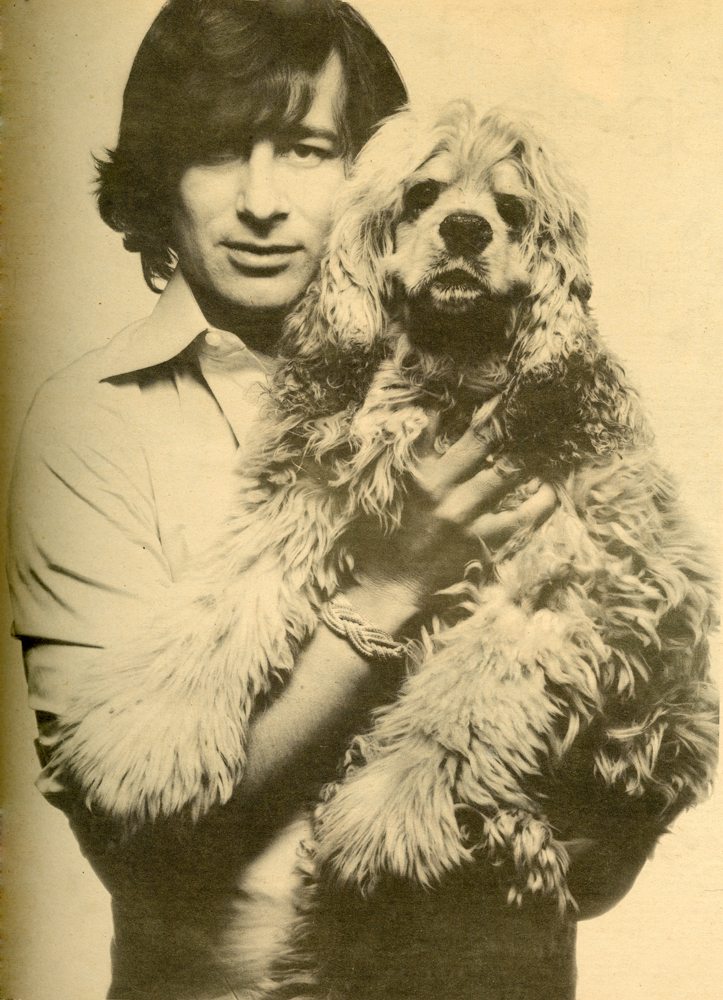

ABOVE: STEVEN SPIELBERG WITH HIS DOG ELMER, WHO JUST GOT THE PART IN WHIZ.

Next week, Steven Spielberg’s film adaptation of Roald Dahl’s novel The BFG will open in theaters across the country. The BFG follows the adventures of 10-year-old Sophie and her new friend, the 24-foot-tall Big Friendly Giant. Together, they traverse Europe, running into other not-so-friendly giants, and eventually arrive in London, where they enlist Queen Victoria’s help to rid the world of harmful giants. Considering Spielberg’s unrivaled reputation (for those who don’t know, he is a co-founder of DreamWorks Studios, has received three Academy Awards, and is the highest-grossing director in history), we have no doubt that The BFG will be a box office success.

Before the release of the animated movie, we decided to revisit an interview with a fresh-faced, long-haired Spielberg from May 1977. The young director discusses notions that are undoubtedly comical now, including how he laughed when his now long-time collaborator John Williams played him the iconic Jaws theme song. —Ethan Sapienza

Steven Spielberg: From Jaws to Paws

By Susan Pile & Tere Tereba

We caught up with director Steven Spielberg the week he was leaving Los Angeles to shoot the last big scene in his new film, Close Encounters of the Third Kind—between injections as it were, for he was getting ready for a crowd scene in India with 10,000 extras and Francois Truffaut. The interview had originally been scheduled to take place at his house in Laurel Canyon, where we anticipated many opportunities to sniff out the personality he seems to guard so well from the press. At the last minute, Columbia Pictures relocated us to his new house at the top of Benedict Canyon, where he had been sleeping for the past few nights. It is a decidedly unpretentious working domicile, which Steven is having decorated by his friend Joe Alves, who did the set decoration on Jaws, Sugarland Express, and Close Encounters. Rick Fields, son of Verna (Academy Award winning editor of Jaws and Vice President of Universal Pictures), led us to the pool house where Steven, in jeans and a sweatshirt, carrying a can of Dr. Pepper and being followed frenetically by his dog Elmer, joined us a few minutes later.

INTERVIEW: Should you let your dog in?

STEVEN SPIELBERG: He’s an outdoor dog. He’s really a very spoiled cocker spaniel… Elmer, no. No! Go away. I don’t want him to jump on you.

INTERVIEW: This is a great house.

SPIELBERG: It’s brand new. I mean I’m brand new; the house is not.

INTERVIEW: How old is the house?

SPIELBERG: Five years. It was built to look 30 years old. This neighborhood has popped up in the last five years. Before, there were no neighbors anywhere.

INTERVIEW: We were talking that this is the neighborhood that Leland Hayward used to live in.

SPIELBERG: Leland Hayward used to live here?

INTERVIEW: Yes, in the ’40s, because in Brooke’s book [Haywire, by Brooke Hayward] it tells about how [Edward L.] Doheny offered to sell Leland this area off of the Cherokee, and he was living up here on a farm in the early ’30s and he turned it down for a very small amount of money. Of course, then it was already starting to build up. I guess, he had a lot of land.

SPIELBERG: He sure did. This was all his, all this area. The Dohenys owned Cherokee and almost up to Mulholland. This had been parceled out about ten years ago, and it’s really parceled. I’ve never been in a helicopter, I’m afraid to fly, but if I ever get enough courage to go up in a helicopter I bet you anything the houses here are as close to each other as a tract housing area like Sherman Oaks or Encino.

INTERVIEW: We were a little dismayed that you were at the new house, because you are Mr. Nice Guy, and we don’t have any dish on you, so we wanted to snoop around your place, check out what’s on the walls and your record collection.

SPIELBERG: I’ll tell you what’s in my record collection. Topping the list of records, I have about 760—it changes every week—soundtrack recordings.

INTERVIEW: Stock soundtracks?

SPIELBERG: Three quarters of the records are stock, and the rest are collectors items.

INTERVIEW: Do your soundtracks go back into the ’20s or what?

SPIELBERG: You can’t go back into the ’20s. They didn’t begin putting them out until…

INTERVIEW: I mean the talkies.

SPIELBERG: But those are bad reproductions. All the albums I’m interested in getting are the albums that begin in about 1950 when soundtracks became popular.

INTERVIEW: They’re so popular now.

SPIELBERG: And they’re so rare. I mean certain records—like The Horse Soldiers. I just got a copy of The Horse Soldiers which is a very rare piece of acetate.

INTERVIEW: Are you a John Ford fan?

SPIELBERG: Ah, yes. A major John Ford fan. The score that I want more than anything else—I will trade an original Touch of Evil, one Horse Soldiers, one King of Kings and any early Tiomkin for The Searchers. But I don’t think The Searchers was even an album. I think The Searchers is sheet music somewhere in the Warner Bros. Library and you’re gonna have to get Elmer Bernstein’s Record club or Charles Gerhardt with the London Symphony Orchestra to record this.

INTERVIEW: I should have gotten To Kill a Mockingbird. That’s the most beautiful.

SPIELBERG: Oh, I have that! I just got that today, because my secretary knows Elmer Bernstein, and she just came over this morning with a copy of To Kill a Mockingbird. Pretty, isn’t it? You know another very pretty thing is Jenny Goldsmith’s A Patch of Blue. Max Steiner was probably the best composer for film ever to have lived. The one classical composer who was born to score movies and never did [Bela] Bartok.

INTERVIEW: Well, they weren’t around.

SPIELBERG: He was around. Bartok’s Symphony for String, Percussion and Cellist was commissioned in 1936. See, [Erich Wolfgang] Korngold could also have become a Bartok or a [Jean] Sibelius, but he went to movies, and he brought a lot of classical music to film. Just like [Sergei] Prokofiev, who scored a number of Russian movies. [Sergei] Eisenstein used Prokofiev.

INTERVIEW: Do you really work closely with your composer?

SPIELBERG: Very closely… I have a great relationship with John Williams.

INTERVIEW: I really liked the Jaws music, sort that “Down to the Sea in Ships” type of thing.

SPIELBERG: Well, John and I sat together and listened to a lot of Vaughn Williams and [Igor] Stravinsky, and then he went off and composed on the piano. Before he orchestrates he asks me to come over. I sit with him, and he plays the entire score on the piano, and I’m able to make comments, changes or whatever right there, which is really a luxury. John called me over to his house very excited. He sat at the piano and said, “Here’s the theme from Jaws.” He began playing this very primordial, repetition on the lower notes. I thought he was fooling around. I mean “da da Dah da Dah da.” I began to laugh, and John said, “Oh, no, this is serious. I mean it. This is Jaws.” And I listened to it again and it grew on me. It wasn’t something that exploded as a correct choice. At first I thought it was too primitive. I wanted something a little more melodic for the shark, and then Johnny said, “What you don’t hear is the L-Shaped Room… You have made yourself a popcorn movie.” And he was absolutely right.

INTERVIEW: We were also talking yesterday about how schizophrenic being a director must be. In a way, you have to exercise so much control and then you have to give it up at the same time.

SPIELBERG: Yeah. What you really have to do is, you have to become everybody in order to understand where everybody’s head is at. At some time in your life you had to have experience in that area so at least when somebody comes crying to you that the clothes don’t fit you can understand “inseam.” It’s funny, you make friends and you lose friends when you’re making a movie. I’ve been told that I’m a very different person on the set than I am in postproduction when the movie’s over and I’m editing, in that I get so wound up in the film that I become selfless to the point where I lose too much weight. All of my regular routine habits go out the window. I don’t get enough sleep at night, and basically I become moody and introspective and not the nicest person to be around, and quite possibly entirely celibate for the period of principal photography. In a way you’re fucking your movie when you’re making a movie, and there’s very little room for friends, for family, for anything else.

INTERVIEW: We know that you storyboard everything.

SPIELBERG: I storyboard, yeah. And sometimes what I’ll do just out of sheer boredom is that I’ll say, “Four months ago this worked in my head, and I was excited about shooting it, but now I don’t see the film the same way.” It’s just not as interesting as it was four months ago, so I’ll change it. I’ll change it usually ahead of time so I’ll have something rather than spontaneously on the set. But on Jaws, the whole third act was a concept I had in my head which I had the art director put on paper that I adhered to out of necessity. There were over 400 individual drawings, pen and ink drawings. It basically gives me the security to get up in the morning. It’s like doing your homework.

INTERVIEW: Plus, being only 29-years-old, you really have the burden of so much responsibility.

SPIELBERG: The age doesn’t really matter to me as it seems to matter to other people. A lot of people think that youth or age is the total sum of your knowledge about anything, and it’s absolutely untrue. I think I might have even known more five years ago than I do now.

INTERVIEW: You’re talking about how you get involved totally during the shooting time, but are these your happiest moments, when you’re losing weight, and…?

SPIELBERG: No, my happiest moments are when I’m putting the picture together in postproduction and things are working as I’ve planned. There are two great rewards that I heap upon myself when I’m directing. The first is when I first get the idea months before I start shooting, and I jump up and down and I drink my Dr. Pepper and I go out and celebrate. And the second nicest moment is when I’m in the editing room and I cut that concept together and it works. The best laid plans actually paid off. That’s the second celebration. In between, the making of the movie is just pure warm shit. I was lucky on Jaws and Close Encounters… I worked with people I liked. [Roy] Scheider and [Richard] Dreyfus are terrific. They always keep your spirits up, especially Roy. But the making of the movie and the routine of making the movie is a lot like being in a Spanish prison for five years on a marijuana breakdown, you know?

INTERVIEW: It’s the circles of hell. It’s Dante.

SPIELBERG: Truffaut says the best thing about making a movie, and I can’t quote him exactly, but at one point Truffaut said that making a movie is like a stagecoach ride through the Old West: at first you wish for a pleasant trip, and after a while you just hope you reach your destination.

[Steven’s assistant, Rick Fields, Verna’s son, comes in.]

RICK FIELDS: They need you at the cutting room. As soon as possible.

INTERVIEW: Oh, no. Oh, no. We’ve got a million more questions to ask.

SPIELBERG: [To Fields] Another 15 minutes, okay?

INTERVIEW: Okay, so we better talk about Close Encounters pretty fast.

SPIELBERG: Oh, no. Go down your list, I’m looking at my record collection right now in my mind.

INTERVIEW: Well, forget it. What did you make in that hangar in Mobile? Is it the Statue of Liberty?

SPIELBERG: No, we did a lot of interesting things in that hangar. One of the main things we did was try to get the air conditioning to work. It was in the middle of the South, in the middle of the summer, 95 to 100 degrees inside with men working 100-feet up on catwalks where the temperature rose to about 150. It was the worst kind of steam shower effect you’ve ever experienced in your lives. And, it was once again another survival movie. For some reason I get involved with these movies where the environment is more difficult to control than the subject matter. I can’t talk too much about the hangars and all the secrets of Close Encounters. I can just say that it’s a movie about the UFO phenomenon, worldwide. It’s not a documentary. It’s a very exciting adventure movie with Richard Dreyfus and Francois Truffaut and Teri Garr and Melinda Dillon. And, it just answers some questions I think a lot of people have been asking, if you believe the Gallup Polls, about, you know, what that thing is at night when you look up into the sky when you’re on a camping trip.

INTERVIEW: Have you had any personal experiences, Steven?

SPIELBERG: I haven’t yet, no. I wish I could have. I conceived and directed this movie based on a lot of written material and a lot of want-to-see. I really want there to be more to this than misperceptions of conventional objects and natural phenomena.

INTERVIEW: Why is there this veil of secrecy around it?

SPIELBERG: Only because…

INTERVIEW: Someone will rip it off?

SPIELBERG: That’s only part of it. To talk about a movie before it comes out, any movie—I wouldn’t be this secret with a comedy, I think, or with a best seller, because anybody can go out and read all they’re interested in. What the press was interested in was why I was changing Jaws, why I threw out the novel. What I did really was an original based on the novel—that’s the interest there, and that’s okay to talk about. But on a picture like this, which is an original idea, there are a lot of surprises that I just don’t want to give away eight months before the picture’s due to come out. It is a sociological study about people who are dislocated by extraordinary events they can’t possibly cope with or understand, based on the way they’ve been brought up and what they’ve been taught about life science. It’s a whole different movie. I don’t know how these projects get to me, but somehow… Close Encounters was the only project that was on my mind for three years, and I just had to reach the point in my career where I had enough autonomy to make this movie right, as opposed to having to make it in twenty days for a million dollars. Maybe I’ll look back and wish I had made it for a million dollars in twenty days, but right now it couldn’t have been made the way it’s coming out had I not had the time and the money.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE MAY 1977 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs on Wednesdays. For more, click here.