Human, Nature: Julia Loktev on The Loneliest Planet

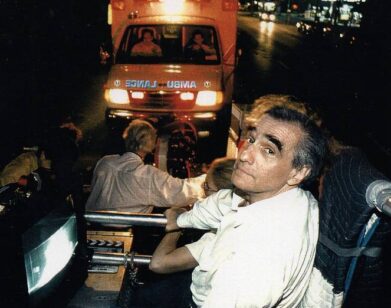

ABOVE: GAEL GARCÍA BERNAL, BIDZINA GUAJABIDZE, AND HANI FURSTENBERG IN JULIA LOKTEV’S THE LONELIEST PLANET. PHOTO COURTESY OF IFC FILMS

Julia Loktev’s third feature, The Loneliest Planet, may cheekily take its title from the ubiquitous travel guides—but in it, the Russian-born, Colorado-raised filmmaker has crafted a pared-down, deeply affecting pastoral drama that meditates on the nature of trust and the capabilities of language.

Set in the Caucasus Mountains in Georgia, the film follows two backpackers, Alex (Gael García Bernal) and Nica (Israeli actress Hani Furstenberg), a couple engaged and in love, out to rustle up some adventure before their impending nuptials. Led by Dato, their guide (Bidzina Guajabidze), Alex and Nica set out on a camping expedition, traversing the overwhelmingly beautiful, highly textured terrain. Dialogue is minimal: the physical gesture, along with the presence of the expansive landscape, takes precedence.

At the film’s climax, a brief, yet unhinging, moment transpires between the two lovers. The action itself is subtle, but it roots itself between Alex and Nica, and as the uncertainty and tension between the couple grows, the ambiguities of language, what is both said and unsaid, through verbal or physical means, become critical to their perceptions of self and the state of their relationship.

Loktev, herself a seasoned traveler, recently spoke with Interview about the film’s sense of place, the relationship between the guide and guided, the multiple interpretations of Alex and Nica’s turning point, and creating a film that is largely silent, but loaded with nuance.

COLLEEN KELSEY: What made you first interested in Tom Bissell’s short story “Expensive Trips Nowhere,” and why did you want to adapt it?

JULIA LOKTEV: I thought of this story completely randomly, because I saw the book that it was a part of, God Lives in St. Petersburg, and I was born in St. Petersburg, so I found it irresistible. It’s a collection of short stories, mostly set in central Asia, which I’ve traveled across. I put it away in the back of my mind, and then I remembered it while I was traveling in Georgia. I was in Georgia for a film festival, and somehow being there made me think of this one short story in the book. There was a lightbulb moment of being like, “Ooh! That would make a good movie!”

KELSEY: Did you always want to specifically use the Caucasus for Alex and Nica’s story? Or could it be set in another locale?

LOKTEV: The original story was set in Kazakhstan, which I’ve been in, but somehow Georgia just seemed right because of the landscape—very specifically, the way that the mountains look. Strangely enough, Kazakhstan doesn’t look that different from the way that the Rocky Mountains look. It doesn’t look that different than Colorado. Georgia is this very unique-looking landscape, because it looks like nothing you know.

KELSEY: It’s really otherworldly, mythical almost.

LOKTEV: It’s slightly science-fiction-like, no? I was very picky about the kind of landscape that the film would have, because the landscape is almost like music in the film. It sets, completely, the mood of the film. I didn’t want something that was rocky, that was arid. I also didn’t want trees. These mountains are huge and green and open; they just seemed so right for the story.

KELSEY: It really asserts itself as a fourth character.

LOKTEV: Exactly. I plotted the film in terms of the narrative. I had a storyboard of locations, so that in a sense, the more ugly things get between them, the more beautiful the landscape becomes.

KELSEY: We don’t know a lot about the background of Alex and Nica, except for what’s presented to us in the film. It’s reminiscent of the main character in your previous film, Day Night Day Night. The films are not so much rooted in context and are more of the moment. Do you see any other connections, or rather, a progression, in terms of the two films?

LOKTEV: There’s always a connection. I think I always try to do something quite radically different, but there are probably connections that sneak in. But, for me not knowing the background, it’s not so much that it’s making a point of this, but it seemed organic to the story. It’s about a couple who are engaged to be married, so they’re not there telling each other, you know, their family histories or what they do in life, because they know each other’s family history. I don’t like it when there’s dialogue that seems to be written for the audience’s sake, so I wanted them to talk about the things that you talk about when you’re traveling, which is like, “Did you shit today?” It shows an intimacy between them.

KELSEY: The film is as much about silence between people as it is about language and miscommunication. Did keeping dialogue to a minimum and emphasizing the physical take importance?

LOKTEV: Absolutely. I don’t know if it’s [the physical] more than dialogue. I sort of think of different kinds of communications, the way bodies communicate, but also language too. You said something very close to what a friend of mine said, which was that it’s a film, strangely, that’s very silent, but it’s about language. It’s the way that language is used when you’re traveling, when you’re exchanging very basic words in each other’s languages. That keeps playing into the film, the misuse of language, but also in between that, how much they say when they’re not talking.

KELSEY: You didn’t use stereotypical-looking American tourists for Alex and Nica’s roles. How did you decide to cast Gael and Hani, who are from international backgrounds?

LOKTEV: I wanted them to reflect the kind of Americans that I know, and so many people I know are from somewhere else. I don’t have an accent, but I was born in Russia. So many of my friends were born somewhere else, and that’s just an organic part of my world. I also wanted to reflect the people that I’ve met in guesthouses and youth hostels when I’ve traveled, who are not the fanny-pack, white-sneaker tourists, but who are experienced tourists. I wanted to be honest about experience, so that they wouldn’t be a parody. I wanted, as much as possible, to see them as real people. The same with the guide. I tried very hard to see him as a complex person.

KELSEY: And Bidzina, who plays the guide, is the top mountaineer in Georgia-how did you recruit him to act in the film?

LOKTEV: He is amazing. He never acted before. Basically, I had met every actor who spoke any English in Georgia that was in that age range, and they weren’t right. I started meeting guides, because a guide is a performer. You put on a performance every time you take a group or a couple out; you put on a show. We started meeting different guides, and then somehow through Facebook, our Georgian producer got in touch with the mountaineers and they all led us to the king of the mountaineers, Bidzina Gujabidze, who said, “Thank you very much, but I have an expedition planned to the Himalayas. I have no interest in being in a movie.” But he somehow came in and auditioned anyway. Then his kids found out about it, and it’s really thanks to them that he did the movie, because they were pestering him until he would agree to it. It’s a very different character, actually, from him. It’s not his story at all. There’s something of sick joke of taking Georgia’s top mountaineer, who’s climbed all over the world, climbed Everest twice… he’s dressed like a village guy who takes trekkers.

KELSEY: The relationship between the guide and the guided is a really tenuous one. Because you depend on them, you have an intimate relationship with them, but you’re engaged in a business exchange with them. Did you want to explore that dynamic between Dato and the couple?

LOKTEV: I was so fascinated and excited by this, because it’s something that happens every day. People all over the world go somewhere, and you hire someone to guide you through this place. It can be in a museum, but usually it’s somewhere out in nature. You’re bonding because you’re going seven nights together on this expedition, but one of the things that’s interesting to me about it, is that the traveler is there to listen. They’re really an audience the whole time. He is leading the show and they’re being respectful listeners. And on the one hand they’ve hired him, on the other hand they would be completely lost without him, and then it’s friendly, but it’s also an economic relationship.

KELSEY: I wanted to talk about the moment in the film when things shift in Alex and Nica’s relationship. It’s very much tied to gender roles and expectations. What were you thinking about in terms of masculinity and gender relations in contemporary relationships?

LOKTEV: For me, that was the attraction to the short story, initially, because I had no idea how I felt about this turning point. It’s something that happens very quickly, a second, and I think it calls into question what they thought about each other, and what they thought they believed. They don’t know what to make of this moment, and I don’t really know what to make of this moment. I’m attracted to things that I don’t know how I feel about. Maybe I think, I should feel one way, but some part of me feels a very different way, so it’s something that I think they spend the second half of the movie trying to figure out how they feel about it, and how to make sense of it. The thing is, it can’t be undone, but they don’t know what to say about it, they don’t know what to do about it, and I, honestly, don’t know what to say about it either, because it’s something that confuses me and throws me.

KELSEY: There also seems to be two perspectives, some who take issue with it, and those who say, “Oh, this isn’t a big deal at all.”

LOKTEV: Which is wild for me. It says more about the people seeing it than it does about the movie. It’s strange. I’ve had people react to it who are like, “No, this is absolute. There is no future for this couple after this,” and then I’ve had people who say, “What’s the problem?” And I’m kind of in between. For me it’s important to think, the second half of the film is about the same day as the incident, and it’s about this couple who are trying to figure out how they feel about it. And I think it changes from moment to moment. How you feel about something 10 minutes after it happens is maybe a little different than an hour, then maybe a little different than later that night.

KELSEY: In the second half of the film, it feels as if time slows down and every moment is elongated, and you see the ambiguity and uncertainty in the two characters.

LOKTEV: Exactly, and I think they shift in that time. Very subtly, very slowly, they go through changes that are not necessarily always motivated by an action, but are somehow motivated by the passage of time. I think they’re trying to find their way back towards some sort of equilibrium, or back towards what they know.

THE LONELIEST PLANET IS OUT IN LIMITED RELEASE TODAY.