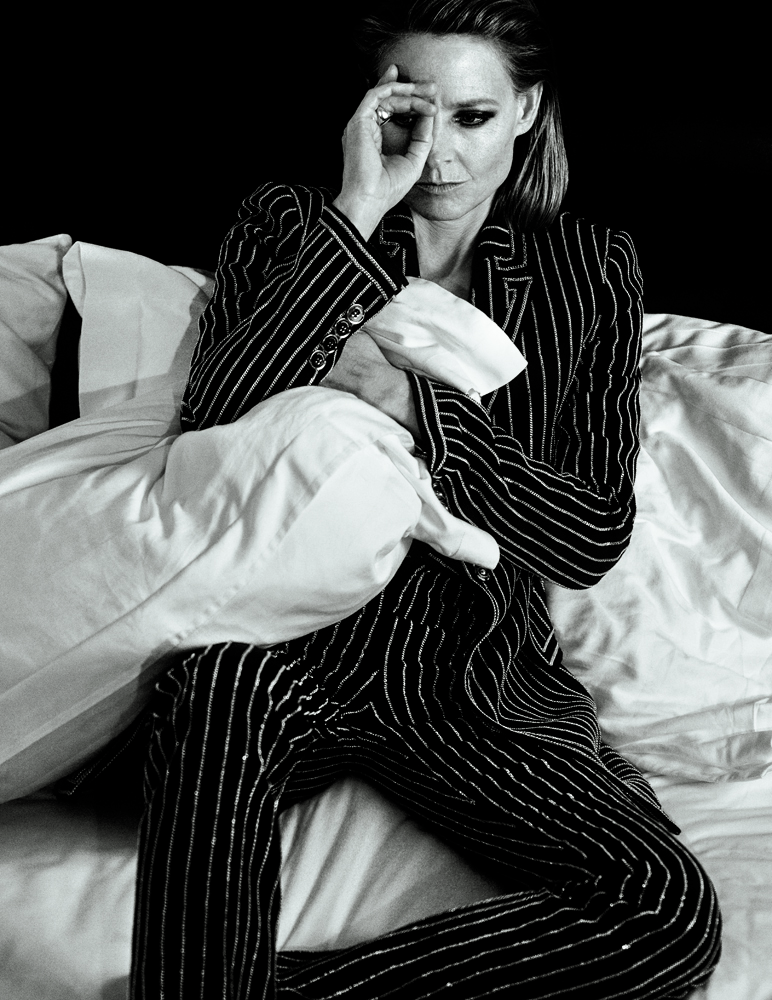

The Legend: Jodie Foster

I can’t IMAGINE ever NOT [WORKING IN FILM] . . . But I am OLDER NOW, and SOMETIMES I WONDER whoI WOULD have BEEN and WHAT ABOUT me WOULD have CHANGED had I NOT had THESE EXPERIENCES as a YOUNG PERSON. JODIE FOSTER

Really, how do you top a role in Martin Scorsese’s masterful Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974) at the age of 12? How about a scene-stealing, and Oscar-nominated performance in his next film, Taxi Driver (1976), at the age of 13? For Jodie Foster, the trajectory has always been upward and steep—even if the ultimate destination was a little unclear, especially to her.

Born in Los Angeles in 1962 and raised by her mother (along with a video village of technicians) from one film set to another, Foster, now 53, hardly even remembers a time before she was an actress. But still she doesn’t feel herself to be a native performer. At Yale, she studied literature, and she says that, even now, she approaches her roles through the written word, through story, and imagery—as a director, in other words. In the late 1980s she began a white-hot run that included a pair of best actress Oscars for her performances in The Accused (1988) and The Silence of the Lambs (1991), as well as her debut as a director, Little Man Tate (1991). Shortly after her fourth Oscar nomination, in 1995, for her work in Nell, she released her second film as a director, the incredibly charming Home for the Holidays (1995), with Holly Hunter and Robert Downey Jr. And, more and more, Foster has found her comfort zone behind the camera, watching rather than being watched.

As she prepares for the release of her fourth film as a director, the Sidney Lumet-like drama Money Monster—starring two of the most watchable actors in film history, George Clooney and Julia Roberts—Foster looked backward through the telescope of time, talking to a brilliant young actress just beginning her career in very Foster-ian form, the Oscar-nominated Saoirse Ronan.

JODIE FOSTER: You know, when I was your age, or younger, I conducted a bunch of interviews for Interview magazine. They actually paid me. I think I was probably 18 or 19. I was in college and I remember feeling, like, “Wow.” I had a real job, and they paid me money, and it was exciting.

SAOIRSE RONAN: Wow, so you were already well into your film career. When exactly did you take a break from film?

FOSTER: I’m not sure … I don’t think I ever really did. I made, like, five movies while I was in college. I think they just weren’t memorable movies. I’ve taken breaks as the years have gone on—I burn out every once in a while. I’m sure you do, too. And I’m sure you will burn out. Maybe at the end of this year, after you’ve done so much.

RONAN: I have to say, I’ve been dealing with so much press for Brooklyn, and now I am rehearsing for a play, and it is hard.

FOSTER: Your whole focus gets shifted. Are you a good multitasker?

RONAN: I’m all right, not as good as my mom is. Maybe because I don’t have kids. I don’t know what you were like when you were on set as a kid, but when I was younger, I would mess about and have a laugh with everyone. I was doing Atonement when I was about 12, and as we went to do this very serious scene, the director Joe [Wright] came up to me … I’d been giggling right up to the beginning of the take. And he came up to me and said, “Okay, you need to be serious now.” I completely idolized him. So, for someone like him, almost like a teacher, to be firm with me, that really stuck with me. And that helped me as I’ve gotten older. When I am on set or rehearsing for the play, the only thing I can talk about is the work I’m doing. In that way, I home in on what I am doing at the time. So maybe I am a terrible multitasker.

FOSTER: It’s a skill that people are born with. Either you’re a focuser or you’re a multitasky person. I am a full-focus person.

RONAN: Are you able to multitask when you’re directing films that you’re in, like The Beaver [2011]?

FOSTER: I’d prefer not to act in the film I’m directing. I think, though, as an actor, you do learn how to turn things on and off quickly and kind of compartmentalize. You learn to accommodate the camera and the other actors, to notice where the boom is and where you mark is, and be able to repeat something a few times. So there is one part of you that is completely immersed in the scene, and then there is the other part of you that is looking over your shoulder and paying attention. You learn how to play the drums and be the conductor who understands where the beat is supposed to go—choreographer and dancer at the same time. At least it’s all a part of the same thing, the same movie. Where I have problems is when I am in the midst of doing something that I am completely focused on, and then I am asked to buy shoes or something.

RONAN: [laughs] You need to buy shoes?

FOSTER: Yeah. I can’t do that.

RONAN: Or have a shower. Or feed myself.

FOSTER: But going back and forth between the press and something like The Crucible must be really crazy and intense.

RONAN: Yeah. Ivo van Hove is directing it, and rehearses in quite an unusual way. We started rehearsals last week and dived straight into the first act, like, five minutes after we all turned up. No warm-ups. We were very intensely immersed in that whole world on day one. It was quite surreal because I’ve never done any theater before.

FOSTER: Me neither.

RONAN: Have you not? People say that in some ways it is very similar. I know what they mean. But the amount of stamina that you need to carry on in theater is something else. I was actually trying to think if you had done theater because obviously you grew up in film.

FOSTER: Well, I did a couple of plays in junior high school, maybe high school, and then I did a play in college.

RONAN: Was everyone really intimidated that Jodie Foster was in a play with them?

FOSTER: They didn’t seem to be. Maybe because they were, like, 18 and overconfident. But it was a weird moment in my life and a weird experience. It made me think, “Gee, I don’t know if I ever want to do this again.” And I love theater. I love going. I love the experience of theater. But I am not sure it’s for me. I think I missed all of the wonderful things … I missed the control that you have in film, and I missed getting it right, really getting it right, the way you hope people will see it. All of the things that people love about theater—the fact that it changes every night and that it’s so spontaneous—all of those things just frighten me.

THE way I APPROACH [acting] is REALLY LOVING STORY. THAT’S my FIRST LOVE—the WORDS. THE WORDS and THE STORYand HOW to CREATE IMAGES. I GUESS I come at THAT as a DIRECTOR. JODIE FOSTER

RONAN: I am glad you said that. Having that control and actually being able to manage something—I suppose because we grew up with it. We grew up with a camera in front of us, and the relationship that you have with the camera is so …

FOSTER: Intimate.

RONAN: Special, yeah. Although I am so happy to be doing this, the freedom that you get really is very different. I certainly don’t feel like I am desperate to run away from a film set. I love the hustle and bustle. Everything is sort of mad right before a take, and then it just settles, and you’ve got these two minutes of a bit of magic. I just love that in film.

FOSTER: It’s a funny thing, isn’t it? All of the thinking and planning that you do to get there, and then, in one minute, in one second, it just doesn’t matter. It goes out the window. You either got it or you didn’t. There is something kind of refreshing about that.

RONAN: You obviously think everything out and like to be organized, paying a lot of attention to the physicality of the character, the look of the person you’re playing.

FOSTER: I guess I do. But I also feel like I’ve learned over the years what is not important, and that is also great: to know what is pointless to spend your energy on, to be more specific. I didn’t grow up really wanting to be an actor. I don’t remember ever not being an actor. I don’t really think I have the personality. I am not very external. I don’t want to dance on the table and do impressions. So I think that the way I approach it is really loving story. That’s my first love—the words. The words and the story and how to create images. I guess I come at that as a director. I think that’s much more in my personality to be a director, so that’s kind of informed my acting.

RONAN: It also sounds like you have been doing it for so long that it’s just part of who you are.

FOSTER: I can’t imagine ever not doing it. I would feel like I would have lost a limb. But I am older now, and sometimes I wonder who I would have been and what about me would have changed had I not had these experiences as a young person. I start revisiting it, like, “Oh, yeah, remember that thing that happened what I was 8? Or that thing that happened when I was 14?” It’s like a movie that goes by and I feel like it became part of my DNA. I am sure you must feel that way too. You were 12 when you made Atonement?

RONAN: Absolutely. I was 12 and I remember everything. I mean, I had done two films before that. The first was actually with Amy Heckerling. It was so brilliant to work with her on my first film. Atonement was the third one I’d done, and I remember how it felt to arrive on set every day. I remember how it felt to get my wig off at the end of the day. I remember how hot it was. It’s so funny listening to you, as someone who started out so young, when you say you’d never decided to be an actor, you just were. I felt the same way. It just happened, and I was so lucky that it did. You just go with it. I remember being on Atonement and it felt very right to be there. There was so much excitement every day. I remember very vividly how it felt to be a child on a film set, and that is actually really important to hold on to for as long as you continue to make films. You need to be childlike, don’t you?

FOSTER: I really did feel like I was surrounded by family members. I didn’t have a dad, and I remember there were all these guys—in the old days, there were no women, except a makeup artist or, occasionally, a script supervisor. So there were just guys who taught me how to, you know, whittle wood, or how to pull focus, and what the camera was doing. And if I was being bratty, they’d sit me down and tell me. There were lots of rules about not being late and making sure that you didn’t spill anything. So it felt a little bit like I was in a family. And when I went home, my family became a little lonely family because it was just me and my mom. Part of my longing to go back to work was wanting to be surrounded by these people who were teaching me things and drinking bad coffee at three in the morning while we were lying around in a bikini in the winter. Somehow it just felt like real life. It felt more like real life than my life.

RONAN: Absolutely. That was my norm. I was a bit older than you when I started, but it was right before you become a teenager, so you’re growing and you’re being shaped constantly by everything that’s going on. I was even thinking recently, going over these Miller pieces of text, and Nick Hornby’s script for Brooklyn, I have learned so much just from being given the chance to live through their words. I feel like it’s really helped me to grow, you know?

FOSTER: I was a literature major in college and that was my thing, books. And when I think about what part of my college experience came back in my work experience, I feel like it was learning how to read deeper, learning how to keep filling the movie up with more and more resonance. I look at characters of yours, like in Lovely Bones or in Hanna, and, I mean, what an experience. What a deep experience.

RONAN: As I’ve gotten older, I appreciate the written word and spoken word more, but Atonement sort of established so much of me. It was a character that didn’t really speak, and I found that a lot of the roles I was gravitating toward after that were kind of nonverbal. They would tell a story through other means. I’m sure you feel that as a director—a very small gesture between one person and another, or a look, or a shift of the head, can say so much more than dialogue can. I’ve found that I’d be the first one to cut lines. Certainly with something like Hanna, which was so physical. And to incorporate action and choreography was completely new for me and opened up a whole new world of storytelling. What about Money Monster? Is it something that is dialogue heavy?

WHEN I was your AGE, it WAS the TIME of THE BRAT PACK, all those JOHN HUGHES MOVIES. THEY were GREAT MOVIES, but I DIDN’T WANT to do THAT STUFF . . . It was like, ‘WHAT’S WRONG with YOU? WHYAREN’T YOU in the BREAKFAST CLUB. JODIE FOSTER

JODIE FOSTER

FOSTER: [laughs] It is. It all happens in real time. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen some of the Sidney Lumet movies, like Dog Day Afternoon [1975] or Network [1976]. They’re real events that happen in real time, and there are all of these different characters experiencing the same thing in different parts of the movie … I am so bad at explaining my films. But it’s in the world of finance and the world of media, and how they connect. It was a big undertaking. A big, mainstream movie, which stars Julia Roberts and George Clooney. But for me, it’s really just a small story about character and people. Everything else is there to serve that beautiful small nugget or story between these two people, exploring the bigger meanings: why money and value get combined. We think, “If I have more money, I am more valuable. If I make more money, I am more valuable.” It’s all sort of wound up with this problem that humans have with their failure. “What do I do to not feel like a failure? I get married or I have children or I make money or I become famous.” All of them in an attempt to not fail. I only have a month and a half to go, so it’s been no sleep and just running on airplanes and running to the finish line with the mix and the music and everything else. It comes out May 13th.

RONAN: And you’ve got kids as well, don’t you?

FOSTER: Oh yeah. In fact, I wanted to tell you that when I saw Atonement, my son, who sort of has your coloring, looked so much like you it was crazy. Of course, now he is a big, strapping 17-year-old. He’s got facial hair and he’s six feet tall and looks nothing like you.

RONAN: Never know how things are going to turn out with me.

FOSTER: [laughs] You never know!

RONAN: Maybe we’re related.

FOSTER: Maybe. I’ve got that Irish thing going on. Lots of Irish in my background.

RONAN: Do you know whereabouts?

FOSTER: County Cork? And, you know, I’ve worked with Neil Jordan, who I really adore. We did The Brave One [2007] together. And he speaks so highly of you. He really loves you.

RONAN: As he does of you, of course. He had a chat with me about how much he loves you. And you know Neil wouldn’t say that unless he meant it.

FOSTER: You guys all must know each other. It’s like a secret little Irish society in New York.

RONAN: It is. Jim Norton, Ciarán Hinds … Liam Neeson is here. And I am trying to plan a sort of celebration because we’ve got the centenary coming up, the centenary of the Easter Rising.

FOSTER: What is that?

RONAN: Well, the 1916 uprising was kind of the most important rebellion in Ireland’s fight for independence that had been going on for 700 years. So it’s a very important moment in history for us. And my name means freedom, so I am kind of gutted that I’m not going at home to celebrate, because it is going to be a huge moment in history for the whole country.

FOSTER: And what do you do when you celebrate it?

RONAN: I think it will probably be the same as what we do every St. Patty’s day, which is wear green and drink a lot of Guinness. And maybe cry a little bit and laugh, and everyone will have to sing a song. That’s how every funeral, christening, and wedding ends up in Ireland. Everyone ends up having to sing a song by the end of it.

FOSTER: I’ve only been to Dublin once, and I had a great time. I got completely soaked because it was rainy.

RONAN: I thought you were going to say you got completely wasted.

FOSTER: [laughs] Not really.

RONAN: Got off the plane and drank a pint right there.

FOSTER: Caitriona Balfe, who is Irish, is also in my movie. I asked her to play her Irish accent in the movie, but her own brogue is so faint that I had to keep pumping it up. You’ve got a pretty serious one.

RONAN: As soon as you tell me you’ve got Irish ancestry, I inadvertently pump up the Irish brogue. I was born over here but grew up my whole life in Ireland and obviously sound very, very Irish. I feel like it’s just one of those things that just charms the socks off of people.

FOSTER: Oh yeah. You’ll get lots of free things.

RONAN: I don’t know what kind of swag I’d get if I were extra Irish. It would just be, like, extra potatoes. Or like a free pint of Guinness.

For more from the Queens of Cool, click here.