David O. Russell is Back in the Neighborhood

ABOVE: JENNIFER LAWRENCE AND BRADLEY COOPER IN DAVID O. RUSSELL’S SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE WEINSTEIN COMPANY

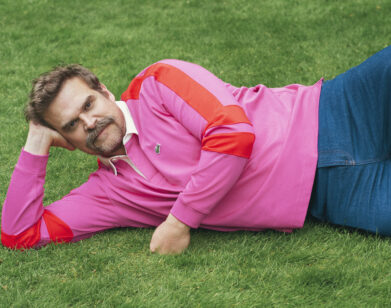

The razor-thin edge between comedy and drama is a line very few filmmakers have successfully navigated. Cameron Crowe, of course, is the master, and preceding him was his hero, Billy Wilder. Alexander Payne also resides in the vicinity; and this year, with Silver Linings Playbook, David O. Russell (who earned Oscar and Golden Globe nominations for 2010’s The Fighter) once again soulfully chronicles an East Coast working-class neighborhood.

Silver Linings Playbook, which Russell wrote and directed, took top honors at the Toronto Film Festival in September, winning the People’s Choice Award—often a harbinger of Oscar’s Best Picture winner (American Beauty, Slumdog Millionaire and fellow Weinstein Company nominee The King’s Speech all won both awards).

Bradley Cooper transcends his rom-com rep (Wedding Crashers, Failure to Launch, He’s Just Not That Into You, Valentine’s Day) to give a performance both nuanced and combustible, as a bipolar high school teacher reeling from his wife’s affair with a colleague. Bewildered and unfiltered, Cooper’s character is released from a mental institution. His father (Robert De Niro), an Eagles fan-turned-bookie, allows him to move back home, provided that he takes his meds—which Cooper promptly ditches, focusing instead on jogging and defying his wife’s restraining order. His silver lining is a tough, mouthy, damaged girl (Jennifer Lawrence) who shares his familiarity with psychotropic drugs and unfortunate predilection for acting out (for Cooper, it’s violent rages; for Lawrence, it’s random promiscuity). Russell audaciously manages to make mental illness hilarious, even as his film makes hairpin turns into heartbreak.

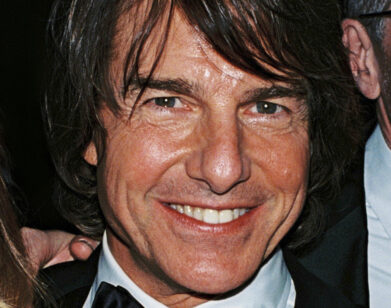

Cooper (whom De Niro championed for the role) is an Irish-Italian native of Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, a Philly suburb near the Italian neighborhood where the film was shot on location in 33 days. To achieve immediacy and spontaneity, Russell, a native New Yorker, often used a hand-held camera and engulfed his actors in the aromas of Italian cooking during scenes. Cooper’s extreme reactions are also frequently heightened with zoom shots. We caught up with Russell to discuss these choices and more.

LORRAINE CWELICH: How did you convey both the drama and humor in mental illness?

DAVID O. RUSSELL: From the sublime to the tragic to the ridiculous. It wasn’t that far from The Fighter‘s Christian Bale character, who is hilarious, and that’s how that character is in real life. If you love these people, they are funny. You marvel at them. Sometimes you want to kill them and are astonished at what’s happening and then they create tragedy. It’s how I see everything, which is why I probably never will do a movie that simply feels bad. I think I land somewhere between Scorsese and Capra in what I’m drawn to emotionally; I’m drawn to very intense emotion. Capra freaked people out when they saw Jimmy Stewart lose it in It’s a Wonderful Life. It was probably one of Jimmy Stewart’s darkest sequences, when he screams at his family. At the same time, that movie has the biggest heart in the world.

CWELICH: How did the idea for the film originate?

RUSSELL: About five years ago, Sydney Pollack gave me the novel by Matthew Quick, which he owned the rights to with his partner Anthony Minghella and Harvey Weinstein. My son has struggles with bipolarity and other matters, and the book grabbed me. I was pleased to write it; it was my first adaptation ever. The characters were fantastic and very complicated. Two very powerful women and two very powerful men, grappling with things in a particular neighborhood’s way. I thought I was going to make it, but it didn’t work out at the time. I made The Fighter, which focused my energy on this kind of a world, which I’ve really come to appreciate as a filmmaker. Then I rewrote it again for this cast. I’ve known Mr. De Niro for a number of years, and we were able to have a personal dialogue about members of our family who have various challenges that they face. That’s always nice when you can have that emotional gateway into material, when it’s very specific and personal to you and you care about it and understand it.

CWELICH: How do you defy characterization as a drama or comedy, particularly a romantic comedy?

RUSSELL: I wouldn’t define it as a romantic comedy. And is The Fighter a fight film? Not really. To me, it’s a film about these specific people. And so if you have an invested emotional drama that’s very specific to a group of people that the romance happens to occur in, that’s the secret [to a good romance] right there. When it’s an original landscape that has real people and integrity, because the world will feel specific and emotional, and the romance will surprise you, as it surprises the characters. These two people are supposed to be staying away from each other, they’re both pariahs, and all of a sudden she’s in the house, in this explosive scene. They’ve been dancing together, which is a loaded gun. I love how uncomfortable people are at the beginning of the movie; Bradley’s a very disturbing, scary character; you don’t know what he’s going to do.

CWELICH: How did you maintain the realism in this film?

RUSSELL: The whole trick is to make it feel like you’re spying on real people’s lives as they get through the day. When I’m writing, I have to trick myself as a writer. If I consciously say, “I’m writing,” I feel all this pressure and somehow it doesn’t feel as real as when it doesn’t seem to count as much. When I write an email where I outlined a whole scene, it just came out of my unconscious, it comes from a deeper place. The same thing happens when the actors go, take after take, and just get lost in it. When you’re in a house, you don’t think about being in the house; you’re just there. You trick yourself into being in the moment, and then it’s just happening and you feel like you’re a voyeur on this world. I discovered it in De Niro’s movies; The Fighter which was an Irish family. I’m Italian-American and Russian Jewish American, and I thought, “I know these people.” That’s a warm feeling that pervades the whole set. We celebrated the holidays in that house, Halloween and Christmas. It felt like there was a life in that house.

CWELICH: Can you talk about casting Jennifer Lawrence in this role?

RUSSELL: Jennifer was very much like the character. She was a late arrival to audition. We had our choice, because it’s a very rich role, of a lot of great actresses. She was an underdog; we thought she was perhaps too young, too inexperienced. And she came in and stole the role at the last second. She possesses many qualities of the character—a great emotional maturity, a great confidence, and also a great vulnerability. She was real and had a lot of charisma and emotion coming from her. And her career was taking off like a rocket during the film, blowing up before our eyes.

CWELICH: Tell me about the rehearsal process.

RUSSELL: A lot of it is about the rhythm. Growing up, I was influenced by De Niro’s work, and that rhythm is the one I related to from my own family. I also write in that rhythm. When actors relate to it, they dial into it like a song, the intensity of the emotion. My goal as a filmmaker is to grab people by the throat with a sustained intensity of emotion that doesn’t really stop. Watching Bradley’s face look like a 10-year-old when his mother kisses him; seeing Mr. De Niro cry, surprised us all; you never know what he’s going to do.

CWELICH: You encourage your actors to prepare and then let it go; to be in the moment.

RUSSELL: Bob [De Niro] had a phrase I’d never heard before; when he had a big monologue, he said, “This is what we call bedroom perfect.” It means when you did it in your hotel room in the mirror, it was perfect. They had that preparation and then they’d show up and forget it. Then it would become something else and that’s the scary part, and the best part—being in the moment.

SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK OPENS FRIDAY.