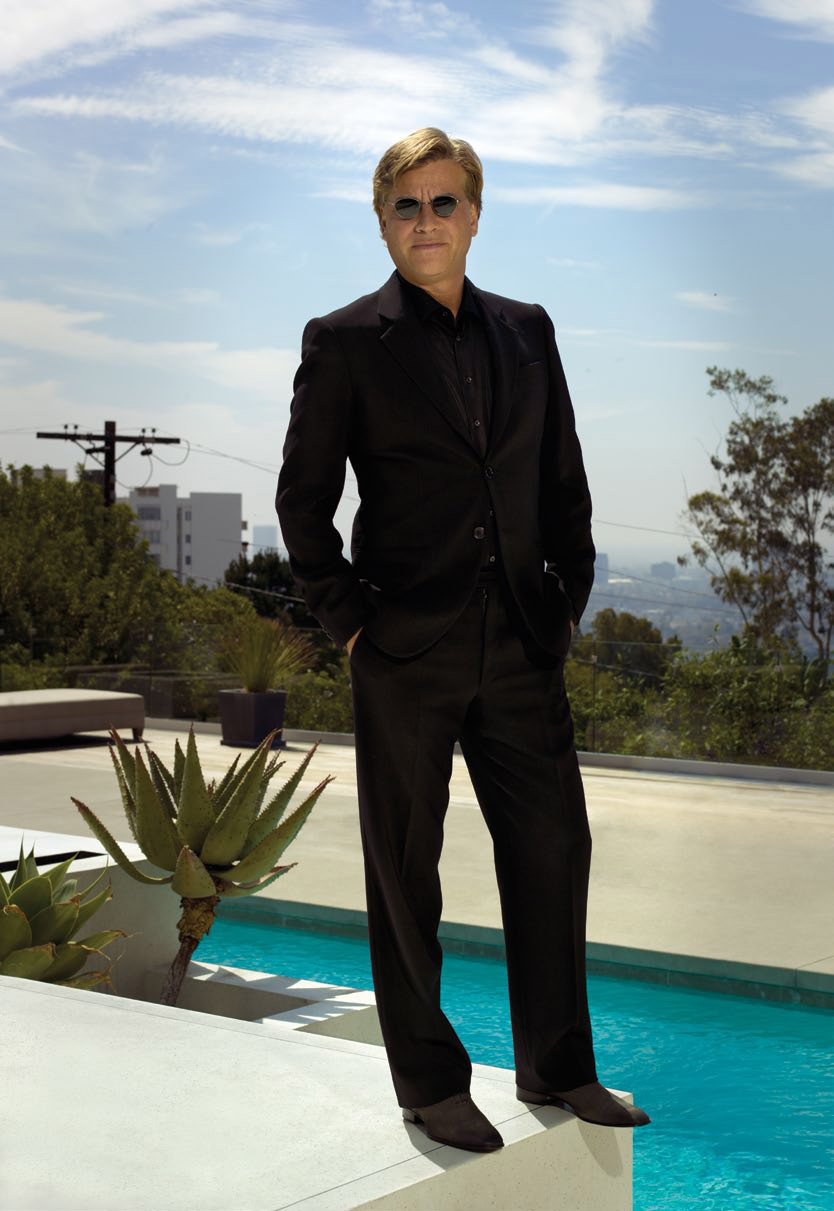

Aaron Sorkin

there was blood everywhere. a friend of mine came over and wanted to take me to the emergency room, but i said, ‘wait! read the scene first because i think it’s good!’Aaron Sorkin

In the first episode of Aaron Sorkin’s new HBO series, The Newsroom, which chronicles the inner workings of a fictional cable news program, the show’s protagonist, a TV newsman named Will McAvoy, played by Jeff Daniels, is asked a seemingly innocuous question by an college student attending a panel: “Can you say why America is the greatest country in the world?” To which Daniels’s character responds, “It’s not the greatest country in the world, professor,” before serving up the kind of freewheeling, vitriol-laced, full-frontal verbal unleashing that has caused critics to often use terms like “machine-gun” and “spitfire” to describe the way people speak in Sorkin’s world, where queries like “How are you today?” elicit long paragraphs, and characters with both egregious blind spots and well-formed opinions are many and multitudinous.

Sorkin, of course, is the dramatist, screenwriter, and producer behind urbane, critically acclaimed shows such as Sports Night (1998-2000) and The West Wing (1999-2006), as well as films such as The Social Network (2010) and Moneyball (2011) (the latter two earning him consecutive Oscar nominations for Best Adapted Screenplay with The Social Network taking home the award). The Newsroom, which premieres in June, marks Sorkin’s first foray into series television since the cancellation of his last show, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, in 2007, and represents his third venture into the self-reflexive waters of making a TV show set in the behind-the-scenes realms of TV. He also recently signed on to adapt Walter Isaacson’s best-selling 2011 biography of Apple guru Steve Jobs for an upcoming biopic.

Daniels heads up an ensemble cast on The Newsroom that includes Emily Mortimer, Sam Waterston, Alison Pill, Dev Patel, John Gallagher Jr., Olivia Munn, and Thomas Sadoski amongst others. He recently spoke with the 50-year-old Sorkin in New York City.

JEFF DANIELS: Recently it was reported that you broke your nose while writing.

AARON SORKIN: Yes.

DANIELS: Do you want to walk us through how that happened?

SORKIN: It was your fault. I was writing the scene that’s in the second episode of The Newsroom where your character, Will, is pushed to the end of his rope. A piece of personal information that he didn’t want to get out accidentally got out because Emily Mortimer’s character, instead of sending an e-mail to Will, sent the e-mail to the entire staff. Then, to make matters worse, one of the staff members tried to delete the e-mail and sent it to corporate, so now 178,000 people have this piece of private information. So then we have a classic comedy move that goes back at least to Jackie Gleason, where you lunge at the character who has done it, played by Thomas Matthews—Chris Matthews’ son—in an I’m-going-to-kill-you move, and John Gallagher Jr.’s character stops you. So I’d gotten up in the middle of the night very excited that I’d figured out this scene, and I’m kind of active when I write. I’m physical. I’m not just typing. When I feel like I’ve really gotten something, I’m up and down, out of the chair, walking around, playing all the parts. And I was in a little home office that I have, kind of playing the scene, and I wandered into the bathroom at the moment of the lunge, and I lunged into the mirror because John Gallagher Jr. wasn’t there to stop me. I just planted my face right in the mirror. I mean, if Scorsese had been shooting the scene, he wouldn’t have used that much blood . . . [Daniels laughs] There was blood everywhere. A friend of mine came over and wanted to take me to the emergency room, but I said, “Wait! Read the scene first because I think it’s good!”

DANIELS: Well, you’re in good company because I hear Hemingway pulled a groin while writing The Old Man and the Sea. [Sorkin laughs] So why writing? You’re smart. You’re educated. You seem to come from good stock. You could have done almost anything.

SORKIN: I’m going to argue with your premise: I think that if I couldn’t write, I would be unemployable. But I also love writing. I’m not particularly comfortable in the actual world—I’m much more comfortable on the page. So if I could have a life where I could just slip the pages under the door and somebody would slip me a meal back, then that would be perfect for me.

DANIELS: Was there a moment or a specific incident that made you realize that this is what you’re supposed to do with your life?

SORKIN: Yeah, because when I was a kid, I wanted to be an actor. I was acting in all the school plays. I went to school for acting. I was really sure that that’s what I wanted to do. So I came to New York to start my life as a struggling actor. Almost immediately, there was a Friday night. It was one of those Friday nights in New York where you feel like everyone in the world has been invited to a party that you haven’t been invited to, and I didn’t have three dollars in my pocket. I was subletting a very tiny studio apartment, and the TV and the stereo were both broken, but there was a typewriter there, and the only way to entertain myself was to stick a piece of paper in it, and that was the first time I had ever written for pleasure. Up until then, writing was just a chore to be gotten through for a school assignment. So I started writing dialogue, and I’d never done that before, but I suddenly just felt a confidence with it that I had never felt as an actor—and I was a pretty cocky actor. I wrote all night long that Friday night, and I really feel like, in many ways, that Friday night has never ended. But it was difficult for me. I didn’t immediately give up my identity as an actor. The first thing I wrote was a one-act play that got accepted at a one-act play festival, and I was in it along with Nathan Lane and a couple of other very good actors. And standing on stage one night, watching them all, in the middle of this scene, I thought, “Boy, these guys are really good. Wouldn’t it be great if all the actors in my play were this good?” And that was the night I stopped being an actor. I’m a playwright. All I care about is the play being good.

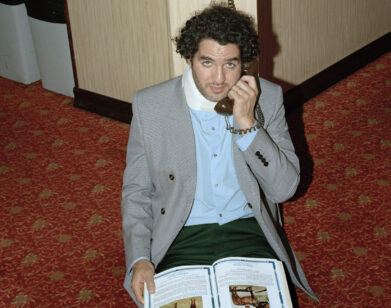

DANIELS: But you still have slipped in as an actor. I mean, you’ve played yourself on Entourage, and in The Social Network you were an ad executive.

SORKIN: [laughs] Yeah. I’ll get cast occasionally as sort of the jerk version of myself, and I have fun doing that. But it’s really better for everyone if I stay behind the camera.

DANIELS: Once you were writing, were there any writers who you wanted to emulate?

SORKIN: The first thing I did was read every play I could get my hands on. There was a place called the Drama Book Shop that used to be on 48th Street and 7th Avenue in New York. You’d walk up a flight of stairs and they have every play ever published. It’s the kind of place where they don’t mind if you just sit there and read—at least if you look broke. And back then I looked broke. But I was greatly influenced by lot of different playwrights. I couldn’t get over Arthur Miller. I couldn’t get over David Mamet. I couldn’t get over Mark Medoff. I would read their plays and go to see any production that I could. Then I went to see the Jim Brooks movie Broadcast News [1987], and that was the first time that it occurred to me that a playwright could write movies too-and that I wanted to do that. So suddenly William Goldman became a hero of mine, and screenplays like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All the President’s Men . . . And then watching M*A*S*H, I realized that a playwright could also write television. So just like any writer or actor or director, success for me was defined by being able to pay the rent and the phone bill by writing. Things like what I’m doing now? You didn’t even dare dream about that. So I just wanted to be a professional writer, and after that one-act that I mentioned, the first full-length play I wrote was A Few Good Men, and it was just by a crazy stroke of luck that it got produced. With a cast of 22, it was too big to do any place other than Broadway, where it’s very hard to have a new play done by a 27-year-old kid who nobody has ever heard of. But it got done, and that’s what took me to Hollywood.

DANIELS: You’re well-known for the pace at which your characters speak. But that isn’t new—it goes back to Preston Sturges and Billy Wilder and others. Were they an influence?

SORKIN: Preston Sturges, Billy Wilder, Howard Hawks, Kaufman and Hart—there was a musicality to the dialogue that all those guys wrote. My parents took me to see plays when I was very little, and very often times to ones that I was too young to understand, like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which I saw when I was 9. But because I couldn’t understand the story, what I really focused on was the language. It sounded like music to me, and I wanted to imitate that sound. As a result, I love dialogue, but I’m very weak with story. I consider plot a necessary intrusion on what I really want to do, which is write snappy dialogue. But when I’m writing, the way the words sound is as important to me as what they mean.

DANIELS: The requirement with you on The Newsroom was that the actors needed to memorize every word—no ad-libbing, paraphrasing, none of that.

SORKIN: Well, I have a lot of respect for people who are great at ad-libbing, and for writers and directors who are able to create a scene in which that works. Judd Apatow is fantastic at it. But as an audience member, I like the sound of something that’s been written—I like it to sound written. And then, of course, you can’t do it without the musicians who can play it. What’s really instructive in that respect, though, is to see a bad production of a David Mamet or Neil Simon play—and by bad production, I mean one with actors who can’t do it. You’re in for a long night.

DANIELS: You hired a lot of theater actors for Newsroom—people who aren’t afraid of words.

SORKIN: Numbers one through six on our call sheet have 13 Tony nominations between them. The very first scene we shot in the pilot was you and Sam Waterston, joined by Tom Sadoski and Alison Pill and David Harbour. We’d kidnapped them off a Broadway stage, too. Tom and Alison had just been doing The House of Blue Leaves. And I think the smartest thing we did was starting with that scene because they knew that the bar was stocked, and then you and Sam shoved it into the stratosphere, and everyone in the cast went, “Oh, god. This is what we’re going to have to do every day. This is what’s expected of us.” It was energizing.

DANIELS: You’re a sucker for romantic comedy.

SORKIN: I sure am.

DANIELS: And unapologetic about it.

SORKIN: [laughs] Well, first of all, I like romance with a capital R, and The Newsroom is certainly romantic and idealistic and swashbuckling. These guys are reaching unrealistically high, and it’s fun to make them slip on banana peels, but their quest is extremely heroic. I do like romantic comedy, and there’s plenty of it in this show, but it’s a slightly more old-fashioned kind, where the characters have one foot in today and another in another time, you know?

DANIELS: Your writing, too, has often ventured into politics, and The Newsroom is no exception.

SORKIN: What’s funny is that I’m not politically sophisticated. All of my experience, training, and education has been in the theater. I had one political experience in my life. I was in sixth grade, and I had a crush on a girl in my class who was volunteering after school at the local McGovern campaign headquarters, so I thought it’d be a pretty good idea if I did, too. We would stuff envelopes together, and one weekend, they put us all in a bunch of buses and vans and took us over to the next town—I grew up in Scarsdale, in Westchester, and they took us over to White Plains, because the Nixon campaign motorcade was going to be driving through, and we were supposed to stand there holding signs saying “McGovern for President.” And that’s precisely what I was doing when a 143-year-old woman came up from behind me, grabbed the sign out of my hand, whacked me in the head with it, threw it on the ground, and stomped on it. So my only political agenda since then has been tied to the slim hope that that woman is still alive and that I’m driving her out of her mind. That is why I write about politics from time to time. It isn’t because I’m trying to convince you of anything, or preach, or educate you. I’m really not in a position to do any of those things. It’s because I like writing romantically and idealistically, and there’s just a treasure trove of stories in that area. Just the whole idea of patriotism and democracy and the struggles that we have in this country . . . I find those things very emotional. As a dramatist, you’re looking for points of friction, and there are all kinds of points of friction in those areas. So that’s why I write about that stuff. But I’m not Clifford Odets, who wrote about politics because that was his way of being an activist. I’ve met activists—I’m not one of them. I’ve never marched anyplace. Those guys are for real.

DANIELS: When I first read the script for the pilot of The Newsroom, and it made me think about how there are probably a lot of people out there like me—and maybe like you—who are unhappy with the way the country is going, and who aren’t necessarily Democrats or Republicans. We’re just angry—we’re pissed off—and you’re such an articulate voice for those of us who get so mad that we cease making sense. Do you write with any kind of consciousness that you might be giving voice to that segment of the population?

SORKIN: You know, your character on The Newsroom especially talks a lot about the sanctity of facts. We are a country that’s going to—and should—disagree forever. I’m a big fan of the two-party system, and I think we arrive at the best answers when the two smartest people in the room disagree, and we can hear a well-informed debate. But we can’t disagree on facts, and that’s what’s happened. We can’t approach this by thinking that the other guys have a sinister motive, that the other guys want to destroy America somehow. That’s lunacy. I’ve never met anyone who has said, “My goal is to make America mediocre.” That’s a kind of hard-right conservative fallacy. But what I do try to do is build a bridge through the world of this newsroom between reality and idealism. We don’t invent any news on this show—it’s all real. And if I can take that and then go to an optimistic place with it, then I fee like I’ve done what I set out to do. What I don’t do is try to guess what it is that other people want and then try to give it to them. I think that’s a bad recipe for good storytelling.

DANIELS: Storytelling has been around since the apes started talking. It’s human nature to love stories.

SORKIN: It is. And humans also know when it’s not a good story. Unless you do this for a living, you may not know exactly why you don’t like a story, but you can’t fool an audience ever. They know when you have it and they know when you don’t.

DANIELS: We were talking about the importance of the pace of the dialogue, and what goes along with that is action. It can be as thrilling as a car chase to see two actors walking down a hallway going back and forth if they’re smart people saying smart things.

SORKIN: I couldn’t agree more. What’s interesting, though, is that I’ve found that the more accomplished a director is, the more secure they are in giving direction that sounds incredibly unsophisticated. Like Mike Nichols on Charlie Wilson’s War [2007] would say, “The trick to doing this is to start speaking as if it’s your turn and don’t stop speaking until your turn is over.”

DANIELS: [laughs] That’s good. I’m a big believer in direction of five words or less.

SORKIN: That’s why Greg Mottola and Alan Poul, our two principal directors on The Newsroom, are so crucial to this show—because it is not at all director-proof. It’s extremely director-sensitive, and if you all are musicians, then they are the conductors.

DANIELS: You’ve got the writer’s room. What do they do? Do they pitch ideas? What do you guys kick around? How does it work?

SORKIN: With The Newsroom, I knew more about the whole season before I started writing than I’ve ever known about any season of television I’ve done before. Now, that’s not saying much—I mean, in the past, on The West Wing, or on other shows, I was really flying by the seat of my pants. I’d be done with one script and have no idea what was going to happen in the next. But with this show, I did know where I was going start and where I was going to end up, and I knew some of the signposts along the way. The Newsroom always takes place in the recent past, so in the writer’s room, the walls are covered with clips and pictures of every news event-politics, culture, sports, human interest-covering our timeline. And when the next episode takes place has less to do with what the next big news event is that we want to cover than it does with where are we in the relationships between the characters, which are really at the heart of the show. This show, though, doesn’t quite work like other shows where the whole writing staff breaks down the season at the beginning, and then I say, “Okay, you’re writing episode two, you’re writing episode three, you’re writing episode four . . .” I do the writing on the show, but I’ve assembled a group of really smart people, a diverse group of thinkers, so that when I’m done with the script, I can go in the room and say, “Okay, what are you guys thinking about?” And they will pitch me ideas, and something will stick to the wall, and I’ll kind build from that. Sometimes it’s easier going than other times, and sometimes you’ll be done with episode five and think, “Not only am I never going to write episode six, I am never going to write anything ever again.” That’s a very real feeling—that I don’t have a story to tell. I mentioned this before, but I’m not a pure storyteller. I have a tough time with story.

DANIELS: So how do you find your way?

SORKIN: I worship at the altar of intention and obstacle. I badly need to know what somebody wants and what’s stopping them from doing it or getting it before I can even write a scene, let alone an episode. But I’ll eventually get something to hang my hat on, and if I know how it starts and I know how it ends, I have pretty much everything I need. But lots of times, I start writing without knowing how it ends, and I call those “Skylab” episodes. Skylab was a satellite that NASA sent up in the 1970s. It went on a six-year mission to gather data. It was an unmanned satellite. And the thing about Skylab was, at the time that they sent it into space, they didn’t yet know how they were going to get it back. They just believed that in the future they would figure out a way to get it back. They didn’t-it ultimately crashed into the Earth’s atmosphere and its parts spread out across a thousand-mile swath in the Indian Ocean. So from time to time, I’ll write a Skylab episode where I’ll start not knowing how I’m going to finish, but just hoping that somewhere in the middle it’s going to occur to me how this ends. If I do know how it ends, then it’s a matter of getting to that place where I was that night that I broke my nose of just having fun—and if I can tell a serious story funny, then I’m ahead of the game. But however you cross the finish line is how you cross the finish line.

DANIELS: When you’re up against a deadline, does that inspire you? Or does it just feel like someone has a gun to your head while you’re trying to type?

SORKIN: The gun to my head. The downside to series television is that the schedule is ferocious. It constantly feels like you have a midterm due that you haven’t started yet. And the worst part is that with a television series, there’s a hard deadline, and so you have to write even when you’re not writing well—and I cannot begin to describe how painful that is.

DANIELS: That can lead to breakthroughs though.

SORKIN: It can, but there are times when we come to a table read, and all I want to do is apologize to the entire cast and crew.

DANIELS: Reality television.

SORKIN: Well, first of all, I think we should stop calling it that.

DANIELS: But is it killing television or just butchering the art of storytelling?

SORKIN: I think it’s worse than that. I think that it’s not good for us as people. It’s pretty much all based on schadenfreude and voyeurism. It’s using other people’s lives as entertainment. It’s not reality—it’s sort of staged fights and cattiness. But in terms of whether or not it’s killing television, I think it’s up to writers to write stuff that is compelling enough that people want to watch that instead of The Real Housewives or something. But in the last decade, I think the best theater in America has been on television.

DANIELS: I agree. That’s where the writing is now.

SORKIN: It’s where the writing is, it’s where the actors are, it’s where the directors are, and it’s where the audience is. One of the biggest challenges in the past for me in working on the networks was that audiences have grown accustomed to television being something that keeps you company-background music, something that you have on while you’re flipping through a magazine, cooking dinner, talking on the phone, putting the kids to bed. But a lot of us write stuff that doesn’t work well as background music—you have to watch it in the way that you’d watch a movie or a play, from beginning to the end. HBO’s audience is accustomed to watching stuff that way. They’re paying for it. They’re not going to use it as background music. But I don’t want to give short shrift to great stuff that’s on network television. I’m evangelical about The Office and Parks and Recreation.

DANIELS: The networks have really raised their game, too. But, man, the creative freedom that you have on pay cable . . . It’s the theater reaching two million people a night.

SORKIN: It absolutely is, and it’s because of the business model of pay cable. They’re not in business with advertisers—they’re in business with the audience.

DANIELS: So finally, who is your favorite Kardashian?

SORKIN: I have to be honest with you: I think they are all lovely women. I am a huge fan of the Kardashians, and I don’t mean to insult them—because the most important thing I want to convey is that I’m crazy about the Kardashians—but I’m not sure which is which. [Daniels laughs] You would not want to put me on a witness stand in a trial where I had to identify a Kardashian. I wouldn’t be a good witness.

Jeff Daniels is a Tony award- and Golden Globe-nominated stage, screen, and television actor.