New Again: Charles James

In New Again, we highlight a piece from Interview’s past that resonates with the present.

Taking quite a different approach from their last collaborative exhibition, Punk: Chaos to Couture, the Met recently announced it will highlight 20th century couturier Charles James at the 2014 Met Ball. A far cry from graffiti walls, Doc Martens, chains, and leather, Charles James: Beyond Fashion will center on the designer’s iconic evening gowns. In addition to the gowns he designed from the ’30s to ’50s, James is known for inventing some of today’s most common silhouettes: wrap-over trousers and spiral cut dresses. The Met restored the collection, which was acquired from the Brooklyn Museum in 2009 and is the largest collection of any designer at any museum in the world. The exhibit will take place at the newly renovated Costume Institute at the Met. To learn more about James’ inspirations and aspirations, we decided to revisit an interview the designer himself from our November 1972 issue. —Emily McDermott

Charles James

by R. Couri Hay

Charles James lives in and among several rooms at the famed Chelsea Hotel, where he has been considered one of the legends in residence for over 10 years. It’s this sort of thing which has given the hotel its peculiar mystique. His rooms house his past, present and future work; and the connection between them all flows freely. The phones are always ringing; people come and go like flowers; and his beagle “Sputnik” sleeps through all of it.

Active in fashion for over 40 years, his shapes are classic, appreciated by scholars around the world. His designs have been drawn by many artists including Matisse and Tchelichew.

He has dressed everybody at some time—film stars, ballerinas, royalty, stage heroines, friends and figures of social prominence. Now past 60 and bursting at the seams with ideas and the energy to carry them out, James inaugurates and completes projects (when permitted to do so), and with the extreme finesse which has characterized the costly career which did all but ruin him. The first to make the zipper and other things fashionable, James is rising again with a new collection readying for a comeback like Chanel after the Second World War.

R. COURI HAY: Recently a picture of your white satin quilted jacket was reprinted in “Quiz” in the Chicago Tribune asking the readers to guess the date of the design. The entire write-in stated the belief that the design was contemporary. It was in fact designed in 1938, proving that your clothes simple refuse to be dated; as shown again by the retrospective showing of your designs and their reacclaim by young and old at the Electric Circus in 1970.

CHARLES JAMES: I don’t think that my work has ever been out of date, in that it was only ahead of its time, therefore it was only a matter of waiting until it became a New Look; and right now I feel that what I’m working on can replace the tacky, fag-hag-drag that which has been passed off as fashion by those who never learned the rudiments of cutting and fitting; usually working from sketches and plagiarizing the process designs produced by the couture markets of the world.

HAY: Critics say your work is too shaped, too structured. How do you answer this?

JAMES: That nothing of worth is produced without the profound study of the structure reduced stage by stage to the minimum.

HAY: What presents trends seem to you significant and, in any way, connected with the arts?

JAMES: Bluejeans, workshirts, denim jackets.

HAY: Why?

JAMES: Because their functionability pinpoints the sexuality of all human beings engaged in work.

HAY: Is it true that blue jeans is the only art form America has produced?

JAMES: Absolutely yes, though one must understand that its origin goes back to the 18th century; it started in what was called Kersey, the early word for Jersey under the Regency launched by Beau Brummel… it was the type of cut and shape; the tight look for pants. The fact that it was developed here in denim because there was a shortage of something else, doesn’t alter the fact that the construction of the silhouette was court invention; it was for the court under the Regent later to become George IV… worn by Beau Brummel; seeking to please Chopin, who was known as also liking the male sex. The blue jean is the only art form in apparel and I’ve been saying this ever since I appeared at the Neiman Marcus Award Show, dressed in jeans, to Mr. Marcus’s horror, but to lessen the blow in a white silk evening jacket and cummerbund; and as a result of this, Mr. Marcus found it necessary to acclaim jeans. This was in 1953. The same applies to peasant costumes for gala occasions worn by women. These derived from and enveloped some centuries earlier for fashionable court ladies. Peasants never would have had the time or access to the artisanship required to develop a fashion worth conserving and finally identifying with their class.

HAY: Where does sex relate to fashion?

JAMES: Sexuality [is] related to [the] precision and tension of designs by which shifting areas of the body are emphasized (at the expense of others—or the significance of others diminished). That loosens… casual look depends, in actuality, on deviation from point of tension as in drawings by great artisans trained by masters.

HAY: Are artisans necessary to create the artisanship forceful trends in fashion which influence the general public?

JAMES: All artists must first of all be artisans, for otherwise they would not know how to direct them; while all artists are not necessarily artisans.

HAY: What is the truth about the talented amateur in fashion design?

JAMES: Tyranny of amateurism today calls for the amateur to buy and successfully woo prominence in press and television media without devoting time to becoming the artisan of his craft.

HAY: I know that you sculpt, draw, and write. Were these offshoots of designing clothes?

JAMES: I have long done everything at once, with very long days which permitted almost no share in social life.

HAY: One doesn’t have to go far to find stylists ripping off your designs and fashion editors forgetting their history; how do you deal with this sort of plagiarism?

JAMES: I get very angry, mainly with myself for not having prevented it, and then I don’t do very much about it, having learned my lesson years before. For instance, a particular person who used my models by making promises which were not kept, has never been sued; because if anyone has liked my work enough to make me work harder and paid some part of the expenses, I automatically fall in love with them.

HAY: Such as you did with Elizabeth Arden despite the rows?

JAMES: Yes, the rows didn’t mean anything. Without her temper she couldn’t have built an empire which grosses $60 million a year.

HAY: The clothes you make are shaped by Charles James rather than merely designed by. What’s the difference?

JAMES: I long since gave up the use of the word design, thinking that it had no validity; whereas, the word shaped implies an activity which only one’s self could be responsible for. The word design is a word attributed to plagiarists by magazines looking for revenue.

HAY: Is the kind of extravagance dead that let you spend 25 thousand dollars on the perfection of an arm hole and have in your showrooms one room of dark blue for the showing of light clothes and another of white for the showing of dark clothes?

JAMES: The studios in polished navy and white with glass furniture were in Chicago in 1927—one of my NY salons in 1945. It was a very original room on the diagonal, with an enormous window through which you could see the workers making clothes. In that ambiance, I established the Japanese workshop for those who were in concentration camps on the West Coast, and, providing jobs were found for them, were permitted to come east to learn a trade. My most important bigger clothes, ball dresses and such, were made in the Japanese workroom; the Japanese having a special quality of precision if rarely invention.

HAY: Your London salon had satin quilted shutters in sky blue, with brocaded mattresses for curtains screening the back view of a ballroom floor in Mayfair, which looked onto a courtyard.

JAMES: Yes. I also painted the courtyard a pale lilac with the penthouse terrace covered with ruby gravel and littered with iron garden tables on which white glass oil lamps lit midnight suppers. But none of this sort of this cost a fraction of the monies wasted on fashion promotion in a day where fashion itself is being slowly destroyed.

My last NY salon had a pale blue flock thrown directly on the walls and ceiling, with one vast mirrored wall and eggshell satin screens dividing space lit by a large chandelier of rock crystal like those in the main ballroom at the Pitti Palace in Florence. But none of this cost a tenth of the sum required to correct mistakes made by workers by which they earned time and a half for extra hours, which work they never should have required had they used their heads.

HAY: McGraw Hill has you under autobiographical book contract and a great many people are nervous of the stories you could tell. Will you tell all?

JAMES: I get much more pleasure out of telling what turned me on than to tell of all the treacheries normally to be expected of people whom you have done something for who are a little timid in their reward. I will print facts, without venom, and without any intent of hurting someone for sheer fun of it. However, facts must be told if they have been falsified.

HAY: The clothes of the ’70s in America are casual, easy, sporty, even the evening clothes. Does this mean that great fashion, as you epitomize it, is dead?

JAMES: No, if you go to a great ball, such as the one given for Desmond Guinness a couple of years ago, where people of all ages, from 80 down to 15 were present, there were very beautiful clothes; but for the main part not were not made in America. The only really funny person was Maxine de la Falaise, whose figure shall we say had blown itself up, and she was wearing what she must have thought to be casual. It seemed to me like something which had come from a thrift shop. In this outfit she was dancing very wildly with a young man who might have been somewhat under half her age—pretty faced, with a touch of hair on his not casually exposed chest.

HAY: In this era of liberation will men return to being great fashion influences as at the time of Louis XIV, who put on wigs, high heels, make-up, wore mad outfits to make his courtiers seem poor and disciplined?

JAMES: They have already become so. The more beautiful fashions turned out in this country are undoubtedly for men. Men have historically worn the maddest things. Maybe the maddest form of design is armor, and armor had to be made functional as well as beautiful; otherwise men were killed.

HAY: Are people still interested in clothes?

JAMES: More than ever, but what has undoubtedly happened is that the middle bracket client, who has a little more money than someone downright poor, but aims at distinction, one who follows magazines with the disastrous influence that they exert, have indeed become uninterested in fashion. All I can say about such women is that they never did have any influence on fashion, responded to it, or set the pace; so it really isn’t any different today than in my youth. Such women never really influenced any trend other than by being responsible for new trends; having made old ones seems trite and vulgar.

HAY: When I think about the influence today, I often think about movie stars, movie stars in politics, movie stars on the covers of the fashion magazine. Were the movie stars of the ’40s fashion pace setters?

JAMES: Very rarely, and I can only quote the late David Selznick who gave me the reason why it was so. He said that a movie was conceived with the idea of running it many years throughout the country, and, mainly be average, in small towns. Small town women would have been affronted by avant-garde fashion. They needed a compromise; the camera distorts very much. It broadens people. Therefore to make them look thin Adrian’s shoulders were far bigger than any that could be worn in a private room without looking funny and common.

HAY: It’s not generally known that you made clothes for movie stars such as Jennifer Jones, Marlene Dietrich, Gypsy Rose Lee and Lillian Tashman, but you did, didn’t you?

JAMES: I made clothes for very special people, and I would say that Gypsy Rose Lee, absolutely; from a personal point of view of originality, judgment, general sense, and unique imagination was very special. Her career as a strip artist was strictly contrived. She really didn’t strip anyway; it was something that is akin to someone who compulsively takes their clothes off in public. She built around this compulsion as an act. Her final act is when she appeared fully dressed, in a dress I made, which was able to be taken apart in five different sections which she draped on five naked girls who accompanied her, and in so doing, practically undressed herself and dressed them. That was her final act, the one that Dorothy Kilgalan wrote the article about in which she said that Gypsy had the training of someone brought up in comparative poverty, and it was necessary for her to continue all her life thinking in terms of petty cash.

HAY: You dressed Paulette Goddard, didn’t you… for film or private life? How did that go?

JAMES: Well, Miss Goddard seemed to think that any design she took home to consider on memo became automatically her property. A transparent lace trouser suit was lent so she could plan where to wear it. Decision was the White House… at a small party given, I think, by Harry Hopkins. We never got the design back until my maid served her with a summons at the side door of the Pierre Hotel. The full price was paid within hours by a former husband bearing the same as myself. She too became a firm friend after this act of discipline on my part.

HAY: Looking in your press books I found a picture of Marlene Dietrich in one of your more extraordinary evening gowns, how did she come to be in that dress?

JAMES: When I remade it for Elizabeth Arden, 10 years after first making it for a lady who was, at that time, 70 and infinitely distinguished and very quiet and witty, Miss Dietrich chose to be photographed in it, and then wished to buy the dress. I thought she looked badly in it, and Miss Arden wouldn’t let it be sold to her. She felt that the way she did her hair was uninspired, and certainly she was extremely grouchy at the photographic sitting. It was a hot day—there was no air conditioning at Miss Arden’s in those days—I got an immense block of ice and put a fan behind it, and it still did not please her.

The dress was in one piece, cut on the bias, with ties on the diagonal opening from which allowed a certain amount of flesh to be seen for those whose figures justified this—such as the divine Dietrich.

HAY: Some say the cinema is the leading art form of this century and, as such gives audience to other art forms such as fashion. Bonnie and Clyde, The Damned, Death in Venice have all influenced fashion. This couldn’t have happened in the ’30s or ’40s.

JAMES: I don’t think it’s happened now. It’s influenced the middle class into thinking that it’s more exciting than it is. I haven’t on the whole seen movies for years except for revivals like The Last Laugh; I believe the last movie I saw was Blow Job by Andy Warhol. I did see the still of Death in Venice, having first read the book in the ’20s. I didn’t want to expunge my own inner vision of this work, so I didn’t see it. I can tell you from reading the book and knowing the people of the time in all ranks of society, that it is very doubtful that a Polish Countess visiting the seaside would have dressed up so dashingly without her husband. I also think it very doubtful that a young boy who fascinated the older writer would have been like a teenage hustler today. The whole mystique of that story was its far greater simplicity. You asked me why I didn’t see many movies and I can only quote Gertrude Stein who, when asked if she’d seen a particular movie said, “No,” and when asked again and again finally she gave a reason, that she had seen Pepi Le Moko and felt it quite unnecessary to see another movie. She felt she had seen the peak expression of movies as an art form.

HAY: Isn’t it true that movie stars usually dress differently in public than they do in private, taking as an example someone you’ve known well such as Jennifer Jones?

JAMES: Jennifer Jones’ wardrobe was copied from dresses made for Millicent Rogers or Mrs. Paley. There are always so many copies made of a design in Paris, perhaps 50 or more, I might take only 10, and they were made for people of extremely critical judgment if not fame. The dresses that I made for Jennifer Jones certainly gave her presence. In my own story figures an actress of great fame. Mrs. Leslie Carter, who was married to my godfather. After a very scandalous divorce, she came to New York and became the mistress of Belasco and played Zsa Zsa until she was 70. With pale green or lilac powder on her face, wearing poison green, and lying on a sofa, with flaming hair, she was a personality like Maxine Elliott and Lily Langtry, and they all wore very good clothes all the time on stage and off.

HAY: Who was the most beautiful woman you ever dressed on stage or in films?

JAMES: The great [Tamara] Karsavina. Russian Prima ballerina. Audiences stood up after her performances, which were sensational in a way difficult to describe.

HAY: Isn’t it true that you specialized in dressing opera stars? Why?

JAMES: Because my mother had studied opera seriously with her school friend Mary Garden whose picture was my pin-up idol at private school. I left two under clouds. Even if for this reason it seemed improper, I sill claim that nothing is more erotic than a beautifully trained woman’s voice. Note tribute after tribute of magnificent pearls and jewels; sometimes thrown to the stage after a triumph with half the audience in tears. Opera, in my opinion, is the greatest art form in the entertainment world.

HAY: Mae Marsh, whom we have mentioned above was certainly one of the greatest stars of her period… a period which stretched back almost the beginning of the film industry. Did you make costumes for her professional career or private wardrobe?

JAMES: For her private wardrobe. She had married prosperously and also was passing through Chicago. A great lady. Perhaps her greatest performance was in that D.W. Griffith epic… Intolerance, which I saw a few months ago at the 23 Street Y. I feel I must stress again the fact that most of the great movie stars in early days had little ambition to go into society. Even their private wardrobes, except in the case of certain stars, came out of the film wardrobes. Therefore they did not appear in Vogue magazine or such media, but in Photoplay… dressed more as their great publics wished to see and knew them from films.

HAY: What other stars from this period did you dress?

JAMES: One of the greatest was Anna Q. Nillson. In the ’30s, towards the end of a fabulous career. She grossed millions for the studios… probably more than famous stars bring in today. I think that she played a silent version of Anna Christie long before Garbo made this her “talkie.” Such stars spend most of their years getting to the studios so early that by seven, they were in full make-up ready for filming. They had their own society and looked more for relaxation than those who came later and inspire drag-queen impersonations, which carry a tragic overtone.

HAY: Getting to a much younger generation, did you not know Ruth Ford when she first came from Columbus, Mississippi?

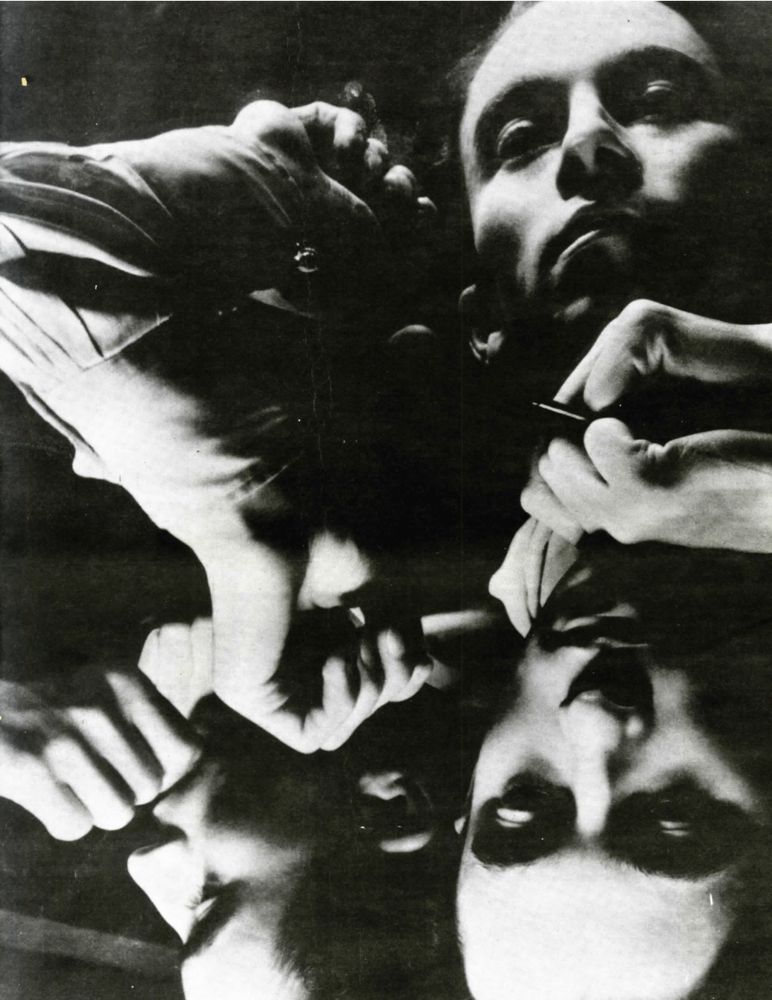

JAMES: No; it was after her early success (I believe) with Orson Welles, Mice and Men. She had come to Paris at the time I was showing my first organized collection to American buyers and the press. Ruth Ford helped me model it, and appeared in one of the most remarkable photographs Beaton ever took of my, at the time, extremely offbeat fashions. I always thought she could have splendidly played the part of Blanche in A Streetcar Named Desire. She did so on the road. She has come a long way recently… and looks almost younger than when she worked for me in during the Paris collection in 1936.

HAY: We spoke about Maxine de la Falaise (McKendry). Didn’t she also model for you in the late forties?

JAMES: Yes; she was then at Schiaparelli’s and took time off to pose most profitably for the Modess account, which I had been retained to direct and “dress.” I was permitted to take several photographers and two professional models to Venice to do two shots. The third was taken in The Opera Comique in Paris by Beaton. We had a marvelous time and the photographs were marvelous.

HAY: I hear you have set up a special teaching course at Pratt Institute. Do you enjoy teaching?

JAMES: All my life, my many workshops accepted apprentices. Many have made their names famous… most of them in the field of theatrical costuming. I don’t have much connection with the School of Fashion Design at Pratt… or, for that matter, at any school of fashion design. My course is given here in the Chelsea where I have a special studio equipped with cutting tables etc. and it is part of the curriculum of the University Without Walls, which is an entity within Pratt Institute, which provides workshop experience in many processes necessary to the mastery of different forms of art.

HAY: Do you hand out grades?

JAMES: Yes. This is a thorn in the flesh of the school design, no doubt. I have, at the present, a student who is far more equipped to teach than any of the entrenched teachers of so-called fashion design. He is of genius rank. Name, Homer Layne. Unconditioned by any New York hogwash, he comes straight from a Tennessee farm. Often knows better to resolve a design than I do. As for fitting different shaped women, I would trust Layne more or, at least as much, as any Paris premiere.

HAY: Is it true that, because you seem to have total recall over a long involvement in fashion, you have become involved in the past rather than the present?

JAMES: Absolutely, no. I have never known what the present is, and consider the past as exposure to processes necessary to forward.

HAY: How would you describe your day to day life?

JAMES: I lead a very retrenched life. I don’t go to clubs, gay or otherwise, because I’m not permitted to drink alcohol by doctor’s orders. It’s true I have little interest in anything other than my work and my children. They have suffered because of my having born the cost of my work. I got out rarely; usually dine at our local Automat… otherwise at Micky’s divine Kansas City… usually at the same table. I have had a birthday party there every July for six years since Antonio introduced me to this scene. I go to places where I hope not to see café society or people whose names haunt the society columns, usually with the help of press agents. I do like to feel I can see and know people who will be remembered for what they have done… be they artists, pimps, dealers, editors, bankers, or the “fallen.”

HAY: Do you feel that because you no longer have a large house and a number of professional employees that you are one of the fallen?

JAMES: No. People like me can only fall so far, then they bounce back with more energy and more to offer than earlier.

HAY: In referring the collection you are currently working on, how did it come about that you suddenly decided, while doing so many things, to make a group of new designs?

JAMES: I told you that all my designing represented a vicarious love affair with women whose beauty I took delight in enhancing. It came about this way. I felt I had found the perfect woman. Near 40 with a figure of an 18-year-old girl. Interested in all that interests me; that’s to say in many areas and art forms at the same time. Above all she combines wit, a beautiful laugh with being a darned good sculptor, as much at home with granite as with marble or teak. She had studied dancing as a young teenager with one of the greatest Spanish dancers of our time—La Argentinita—therefore she can move as beautifully as most women can only move without grace after a few years of marriage. It was more than I could ever resist not to combine a love of literature with the organization of a collection. Workers are hard to find. One has to train them. My designs are being cut and fitted under the supervision of my genius-student. He fights as hard as I once had the time and energy to do to get things as they should be.

HAY: Finally, what would you like to say about yourself?

JAMES: That I only wish I had 20 more years ahead of active work during which I could continue the fight to train young people having the desire to become top artisans, a few of whom will certainly be strong and positive enough to help save the apparel industry from the morass into which it has plunged itself by listening to the wrong voices, and spending on everything but the improvement of workshop processes. Through my clients I may be said to have lived vicariously it is true; but I would wish others who one day can influence fashion—having the guts and capacity to do so, to live through me when I am gone. This will not be precisely tomorrow.

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE NOVEMBER 1972 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.