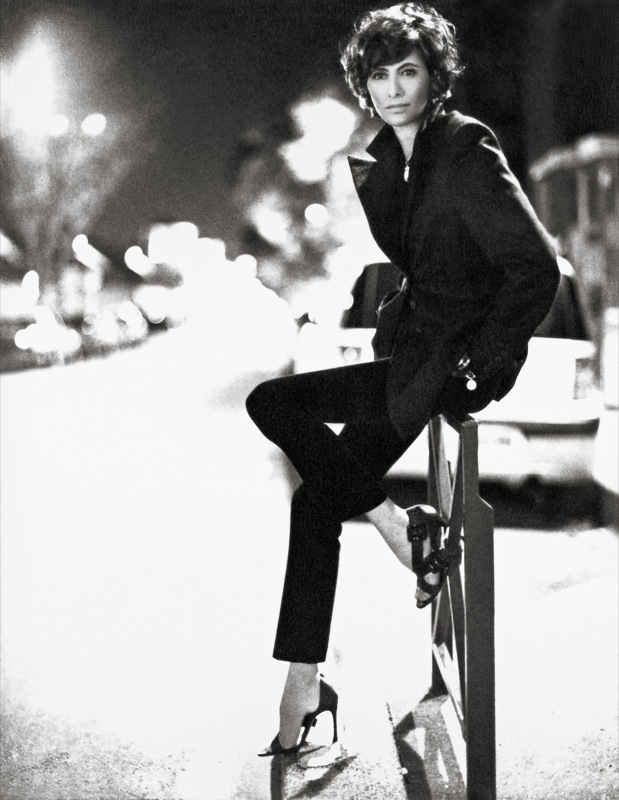

Ines de la Fressange

After having been pr, boutique director, operator, messenger, and everything else, I’m finally in the role I like the most-court jester.Ines de la Fressange

Inès de la Fressange is French chic personified. The 51-year-old beauty was muse to both Mugler and Lagerfeld, a role model of a model whose appeal was as much about personality as cheekbones. How do you top being muse to the nation’s top designers? Only by becoming the face of France, as de la Fressange did when she was chosen as Marianne, the symbol of the country, in 1989. That was then, but de la Fressange is still in the now. It’s no surprise that Tod’s chairman and CEO, Diego Della Valle, tapped her, along with creative director Bruno Frisoni, to reinvent Roger Vivier, the legendary French footwear label. Under her guidance, Vivier has gone from an iconic name of the past to a wildly-expanding hot commodity. It doesn’t hurt that de la Fressange thinks fashion is best served with wine over lunch insatead of as a sales pitch. Sitting down in Vivier’s Paris offices with Colette’s creative director, Sarah, the fashion icon recalls the days when she actually couldn’t get a modeling job.

SARAH: How did you get on board at Roger Vivier?

INÈS DE LA FRESSANGE: Well, that’s why I really love [Diego] Della Valle, because he’s crazy. Instead of going out to find a top business school graduate, for whom it would have taken five years to see the difference between a ballet shoe and a book, he asked me to revive the label. It’s a bit like Balenciaga. Brands like Vivier are pillars—they are monuments of fashion; they are names we don’t forget. But the general public doesn’t necessarily know that and therefore we had to get the name re-known.

S: So you started from scratch?

IF: Exactly. I had met Vivier. He asked to meet me years ago, because he was convinced that I called the shots in Paris and that I only had to pick up the phone and I would get backers, which unfortunately isn’t the case. At the time, he wanted to build up his own company . . .

S: When was this?

IF: It was 1995 or ’96. It wasn’t really the vintage period, so maybe it was a bit too soon. But he was a great teacher and I have a lot of respect for him. All shoe designers were inspired by him, since he went in so many directions. So, when Della Valle proposed my coming over, I loved the idea. This Vivier office didn’t exist. I didn’t have a telephone line, or a bank account. I had a cell phone and a laptop. People were calling me as if I were the press director at Dior. Like, “Send us 10 pictures.” Ten pictures with my phone, you don’t know how long that took! And we’re making the packets ourselves. It was very funny to be putting together a luxury brand on all fours. Even when we moved in here, one minute I was letting in Anna Wintour, and the next I was going to buy garbage cans. I was going to the flea markets to buy furniture. It was getting done the way it was getting done—on a small scale and with a lot of soul and heart and risk. We did fashion like fashion was done before—spontaneously, with joy and freedom, and that’s what created our identity.

S: Now that it’s becoming a great empire, are you still going to keep up that kind of intense creativity?

IF: One thing Della Valle taught me is the power to say no if something isn’t right. That mattered even over sales. Now it’s rolling and finally, after having been PR, boutique director, operator, messenger, and everything else, I’m finally in the role I like the most—court jester. And that’s what I was doing at Chanel before.

S: Do you think having had your own company and being a designer yourself and wearing all of those hats has helped you at Vivier?

IF: Yes, you already know that business has a margin. And it’s a strength to have seen every part of it. Certainly there is still a part of me that liked having my own company and wants to produce a pair of pants, a dress, or a shoe that I can’t find . . .

S: A shoe? You’re exaggerating. I think you’d go suggest it to Bruno [Frisoni, Vivier’s creative director].

IF: Oh, no. Never. I never bother Bruno about anything. I remember one day he had made a kind of boot that was a ballet shoe with the heel inside. I found the inside heel very weird. Six months later, when it was in the stores, I ended up buying it. So, I tell myself that designers are here to shake things up.

S: Your creativity is still expressed in the company, like when you chose to make those bags out of paper.

IF: We had to get Vivier known a bit in Hong Kong. I said to myself, There are all these labels coming into China throwing gloomy receptions at the boutiques, giving out fetid champagne. I wanted them to understand that Vivier was different. That you could be luxurious without being uptight. That you could be French without being conventional and grim. So I did a collection of useless and absurd bags in Hong Kong. I got the label known in two days because of it. It’s important to keep up the idea of the brand, even beyond sales. I did these lunches. I would invite a writer, a psychoanalyst, a banker, a lawyer, a mind reader, a fashion journalist, and an actress, or something like that. And in the room there would be 20,000 sheets of silver leaf and Vivier’s collages . . . The people would laugh a lot, we’d drink a huge amount, the food and wine were exquisite, and then they would leave. The journalist couldn’t believe she was leaving without a press packet. I thought this was the way the name would become known, you see? I remember a lunch with Catherine Deneuve and Bernard Chapuis.

S: Why did you stop the lunches?

IF: Because I don’t like it when things are systematic. I get bored. That’s so French. In fact, I think the essence of fashion is lightness, frivolity, and I’m very nostalgic for the time when Bérard was doing the windows, Cocteau was writing a play, Chanel did the costumes, Bérard did the sets. I don’t have to tell you this, because Colette was the first to have revived the Rue St.-Honoré by precisely doing windows that attract people. And I really like that spontaneous spirit. And so, you’re lucky to be with Colette, because it’s a magic word. With Colette, people say yes, you see, but today, things go through agents, contracts, lawyers.

S: How do you see fashion evolving?

IF: Fashion is made up of paradoxes. There was a key moment in fashion. When the Japanese first arrived—Comme des Garçons, Yohji Yamamoto, and all—I have to humbly admit that I didn’t understand the importance of it at all. It was Jean-Jacques Picart who explained it to me. They had a huge influence in that they showed that aestheticism could be different from prettiness, that there was beauty and that beauty was beyond pretty. They showed girls who had plaster spots on their faces, who looked like they were coming out of a nuclear war, with clodhoppers and no tights, their hair a mess. And then there’s the influence on someone like Giorgio Armani. For example, I knew Armani—I really come off as an old lady here—but his line looked like a Pierre Cardin or an Yves Saint Laurent collection when I first met him. After the Japanese, all of a sudden there were those round collars, girls with square-cut hair, almost no makeup, no jewelry, no nail polish—the beautiful Armani, you know, from the ’80s. That was clearly the influence of the Japanese. But overall when you work in fashion, you’re always in a rush. You’re always a little late, always in a hurry. Every single moment’s important, so you never have enough time to do what you want to do. It’s ridiculous.

S: What are some of your memories from when you started your career as a model?

IF: Listen, I had no luck when I started out as a model. I keep telling people that it’s the only career in the world that you can’t choose for yourself—you have to be chosen. I had a fiancé who looked like a god and he did modeling himself for a while. He was a musician, one of Jim Morrison’s pals. He took me to a modeling agency. They told me I’d have to pluck my eyebrows, and then they let me know that I might as well forget about the whole thing anyway. Later, he had a friend who played the guitar and who lived with the owner of an agency. It was really the best agency at the time. It was called PaulinE, and it was the first agency that took girls who were a little offbeat, not just blonde California surfer–types. Some people might say that it all happened very easily, but it seemed to take forever. I tried Chanel, but they wouldn’t take me. Every time I went to Dior I’d see a really tan woman who couldn’t have been more friendly, who gave me a kiss on both cheeks, but she never hired me. And then there was Kenzo. He was the first to take me [for a fashion show]. I was so atypical, thin as a rail. I did completely off-the-charts stuff. At the last moment Picart put me in 10 shows. I’ve always been very grateful to him . . . He’d say, “Well, of course, that’s French chic, that’s French elegance.”

S: But you were always a symbol of that.

IF: Only in Picart’s mind.

S: In everybody’s mind. When you ask people anywhere who represents French elegance, you’re the one they mention.

IF: I’d take my father’s V-neck sweaters and some

topsiders, which were the ancestors of Converse sneakers, and I’d wear those with jeans and a fur coat.

S: You were improvising then.

IF: Absolutely. One day, I just had white pants, a big white jacket, a white fedora. On a whim, I took a burnt cork and gave myself a big moustache, Aldo Maccione–style, all bent over like an old playboy, and I was clowning around with my big fat moustache. It was so much fun. Now everybody says “sexy” all the time. We absolutely never said “sexy” back then. I was being silly, so I didn’t really stand out, but I was a clown.