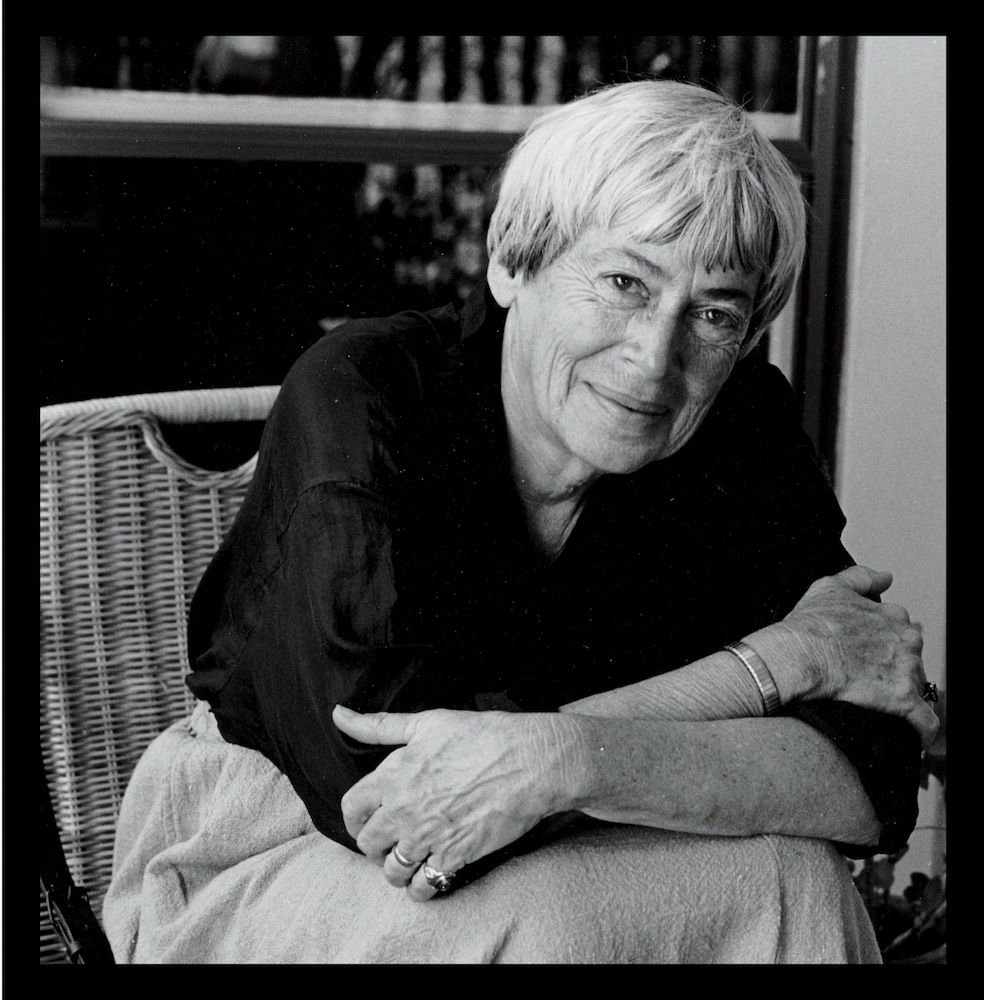

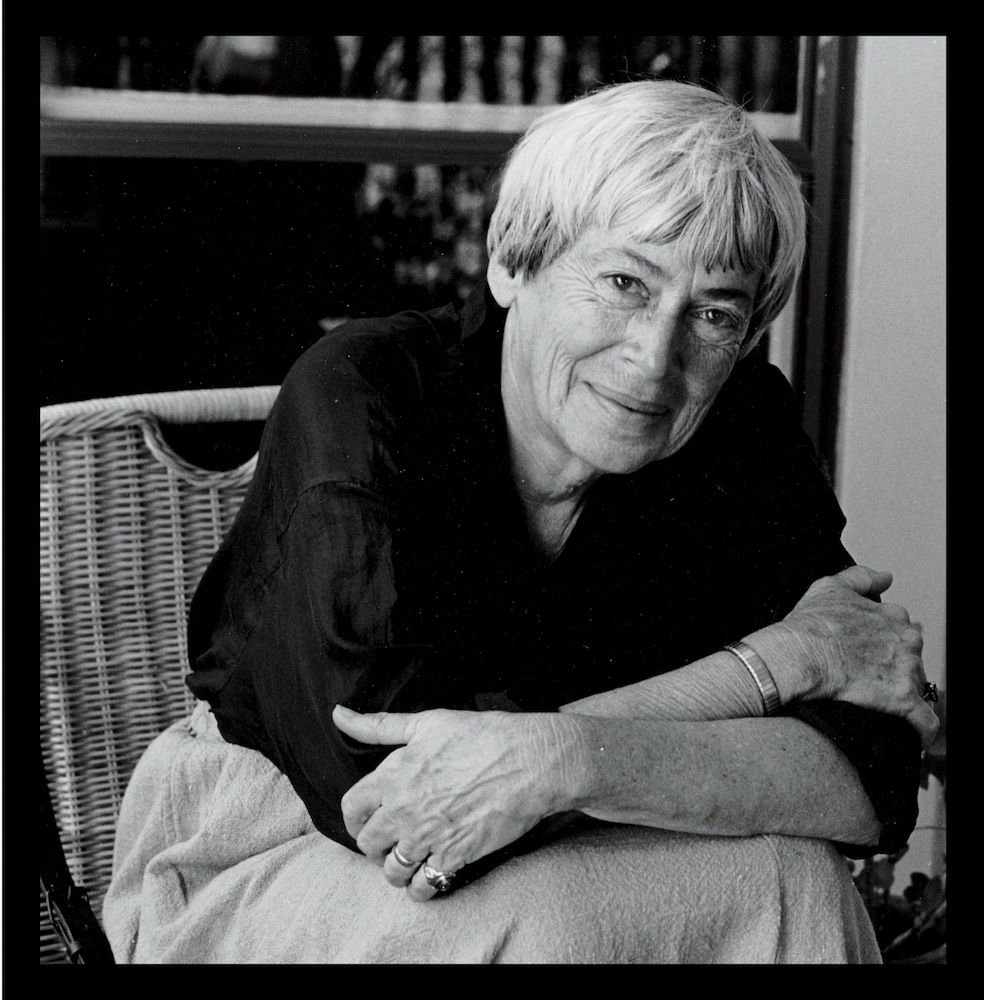

Ursula K. Le Guin

PHOTO: © MARIAN WOOD KOLISCH

THERE’S ALWAYS ROOM FOR ANOTHER STORY. THERE’S ALWAYS ROOM FOR ANOTHER TUNE. URSULA K. LEGUIN

Ursula K. Le Guin’s first novels—set on alien planets and published as trashy head-to-toe double paperbacks by Ace Books—were first unleashed almost half a century ago, in 1966. She was 36. Two years later she published A Wizard of Earthsea, the defining and enduring classic of the genre of wizards going to wizard school. The Left Hand of Darkness, the book that forced writers everywhere to examine how they wrote gender, was first published the very next year and became one of the most acclaimed books of the last century.

She published a dozen books in that first decade, a pile of words built up largely during her thirties that, once released, changed the American conversation about fiction. She is the reigning queen of writing about “the nature of human nature,” as Margaret Atwood once described it, in regards to Le Guin’s “Ekumen” series. Le Guin is one of the rare authors to have twice taken the Hugo and the Nebula awards in the same year. She published three stories in the New Yorker in 1982 alone.

The Terrence Malick-style hiatus of 18 years between her third and fourth Earthsea novels is often referred to by authors of a beloved book when pressured for a follow-up. “The story got stuck,” Le Guin wrote in her afterword to Tehanu, when it finally did appear, in 1990. “I couldn’t go on. It took years of living my own ordinary life and a great deal of learning how to think about such things, mostly from other women.” And yet she also published seven novels, four story collections, three chapbooks and three collections of poetry, two books of criticism, and five children’s books in that interval.

Le Guin will be 86 this October, and is frequently referred to as “the best of” for all manner of things—like best fantasy writer, best science fiction writer, best female writer—all of which is silly, as she both defies and accepts all categorization. Her influence on generations of readers and writers, from George R.R. Martin to Jennifer Egan to David Mitchell, is as evident as it is impossible to overstate. Admired for her quiet daring, her structures, and her inventions, most of all she is revered for her sentences. In 1998, she published Steering the Craft, a trim, little book with the subtitle Exercises and Discussions on Story Writing for the Lone Navigator or the Mutinous Crew. It was intended to teach writers how to be better writers. Finding that first edition lacking for the ever more modern age, she has now rewritten it from “stem to stern” with the new subtitle, “A 21st-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story.”

Le Guin and her husband of more than 60 years, Charles, live in Portland, Oregon, with a cat, now about 4 years old, named Pard.

CHOIRE SICHA: Can anyone be a writer? I used to have strong opinions about this, and I feel like I’ve lost them along the way.

URSULA K. LE GUIN: You want strong opinions? Anybody can write. You know, one of my daughters teaches writing at a community college. She teaches kids how to put sentences together, and then make the sentences hang together so that they can express themselves in writing as well as they do in speaking. Anybody with a normal IQ can manage that. But saying anybody can be a writer is kind of like saying anybody can compose a sonata. Oh, forget it! In any art, there is an initial gift that had to be there. I don’t know how big it has to be, but it’s got to be there.

SICHA: You can’t labor your way into being a poet, can you?

LE GUIN: No. You just can’t. But that’s not to say that being a poet doesn’t take a hell of a lot of work.

SICHA: It really doesn’t seem that rewarding. Is that a terrible thing to say?

LE GUIN: I think there are writers who don’t enjoy writing, and I feel sorry for them. I love it. I don’t care how hard the work is. I would rather be writing than not writing, that’s all there is to it.

SICHA: Poets are a special class. You’re like the wild ponies of the writing world.

LE GUIN: For one thing, the world of poetry that poets have to live in, of who reads them, is so small in the United States. It’s not true elsewhere. But here, it’s not a very big territory, and so they run around spraying the corners and defending their part of it. Poets get very territorial, and that’s too bad; that’s a waste of time.

SICHA: They should be enjoying themselves, and it’s hard to, I bet.

LE GUIN: And you can’t live off it. It’s hard to live off of any kind of artistic writing—fiction or poetry. And then you do have to wonder how many people are really reading your stuff, so the reward has to be in the work. But it is. There’s nothing more rewarding than looking at a poem you wrote and thinking, “Well, at least I think I did it right.”

SICHA: The triumph is private.

LE GUIN: But it’s real. It’s quite real.

SICHA: There’s a sort of growing professional class of writers that may not have had access to being a professional. Before the internet, you would go to your terrible job and then you would write at night. I actually found that system really rewarding, separating out the money and the work.

LE GUIN: On the other hand, if it was a nine-to-five job, and if you had any family obligations and commitments, it’s terribly hard. It worked very much against women, because they were likely to have the nine-to-five job and really be responsible for the household. Doing two jobs is hard enough, but doing three is just impossible. And that’s essentially what an awful lot of women who wanted to write were being asked to do: support themselves, keep the family and household going, and write.

SICHA: And the writing was the first thing to go when things got tough, I’m sure.

LE GUIN: I had only a little taste of that. I did have three kids. But what my husband and I figured—he was a professor and teaching a lot—was that three jobs can be done by two people. He could do his job teaching, I could do my job writing, and the two of us could do the house and the kids. And it worked out great, but it took full collaboration between him and me. See, I cannot write when I’m responsible for a child. They are full-time occupations for me. Either you’re listening out for the kids or you’re writing. So I wrote when the kids went to bed. I wrote between nine and midnight those years. And my husband would listen out if the little guy was sick or something. It worked out. It wasn’t really easy but, you know, you have a lot of energy when you’re young. Sometimes I look back and I think, “How the hell did we do it?” But we did.

SICHA: In the book you talk a lot about things sort of sentence by sentence. And I know when I get the transcript of this conversation I’ll be horrified at the way I speak. I mean, you’re much more articulate than I am.

LE GUIN: But I will be horrified by the way I say kind of and like, and I keep qualifying everything. That’s very feminine. I would like to say it plain, but it always comes out with all these silly qualifiers. There’s a sentence in the book that’s imitating this way of speaking because people do it in writing sometimes too, and they don’t realize that they’re sort of hedging their bets. But sort of, really, is just a noise to me. It’s like like for a teenager, you know?

SICHA: Do you have piles of terrible juvenilia all about in file folders?

LE GUIN: Yes. Do not ask me to show them to anybody! I can’t bear to throw them away.

SICHA: It’s wonderful you kept it all.

LE GUIN: Well, it seems like it would be almost disrespecting my young self to just dump the stuff. I was trying. I wasn’t any good, but I was trying.

SICHA: This is a rude thing to say: you may want to make some choices about the conditions, if you’re going to donate your things to a university or something, about how people may touch those.

LE GUIN: Well, my papers are at the University of Oregon, private letters and all kinds of things. And there are, of course, restrictions on that. I don’t know what I’m going to do with the juvenile stuff. I just can’t quite see myself burning it, which is the only alternative.

SICHA: It seems so dramatic when people burn things like that.

LE GUIN: It is! It’s a terrible thing to do. Things get lost easy enough without their own author destroying them. I can actually put some restrictions on publication of things. I think it’s terrible when they find an early novel by a famous author and dig it out and publish it as if it were something that he or she would have published, when it clearly isn’t. I’m a little conflicted about this whole Harper Lee business …

SICHA: Oh, it all seems very strange.

LE GUIN: And the weirdness going on makes me feel that there really is something wrong here. That she really didn’t want the book published when she was perhaps more capable of thinking it through. But we can’t tell, can we?

SICHA: And the publishing industry had no qualms about publishing it either.

LE GUIN: Most publishers have very few qualms. And corporate publishers these days have no qualms—they don’t know what a qualm is. They wouldn’t know it if it hit them in the face.

SICHA: Readers were delighted that The Left Hand of Darkness is finally an e-book, which it hadn’t been for ages. It felt sort of bittersweet to me too. I hope the arrangement that everyone made was a happy one.

LE GUIN: One reason that I was ready for it to happen and happy that it has happened is that, hopefully, it will put some of the pirates out of business. The terrible, corrupted texts that float around. Some of them are just cheats. So to have a regular, respectably published e-version of it is a good thing for almost any book. The publication history of that book is—talk about weird! But I have been with a new agent the last couple of years and things are going much more rationally.

SICHA: It’s very important to have good counsel in this world.

LE GUIN: It sure is, and that is where I sometimes tremble for the self-published people, who seem to get such various counsel that sometimes sounds to me lunatic. I hope people aren’t being scammed and ripped off too much.

SICHA: One day I’d told a friend that I’d written you a letter, and she said, “I just wrote her a letter too!” And we were both so happy. We expected nothing of it, of course, and I realized, thinking about that, well, it must be frightening at the other end.

LE GUIN: Well, it’s a lot less than it was, since more people simply don’t communicate on paper. The number goes down steadily. I’m kind of touched when people go through the trouble of writing me a letter instead of e-mailing me. I’d actually rather do e-mail. It’s a lot physically easier. You know, I’m 85—I look for shortcuts. But the paper mail from kids is so great. I do try to answer that. I can’t keep up with it, the lovely letters people write me. But I do try to answer the kids. I really do. They’re so insolent sometimes.

SICHA: They’re saucy?

LE GUIN: Well, they tell me how I should have finished the books or what the next Catwings book ought to be or something like that. They have no inhibitions. It’s cool. If I got that from a grown-up, I wouldn’t think it was so cool. I’d say, “Write your own book!” But somebody 8 years old, they identify so passionately with what they read. You can tell. They really are into it.

SICHA: Do you feel like enough of the world gets to you out there in Oregon?

LE GUIN: Yeah. Too much. This is not Tierra del Fuego, you know. I get bored with the parochialness of the East Coast. They think that the news doesn’t get out here and that people out here live in rustic ignorance of real life. It’s embarrassing that people can be so ignorant as East Coast people tend to be of the West Coast-and the whole Midwest-and, of course, so contemptuous of the whole South. So sometimes I have written some rather resentful and snarky things about the urban Northeast-particularly in literature-the notion that nothing is worth writing about except the suburbs of large Eastern cities. Blech. That gets nowhere with me.

SICHA: In the book you return to this idea of writing for art’s sake, which is very much, I feel, out of vogue. We’ve gotten accustomed to talking about money and the commerce of writing and how you should be treated as a writer, and it’s sort of hysterical when you sit back and think about it.

LE GUIN: And there are so many guidebooks to that kind of writing: “How to be a success,” in other words. But I certainly didn’t feel like I had anything to add there, since the way I came into writing was a pretty sure way to not be a success.

SICHA: A few people may talk about the “craft of writing,” but they sound phony. The way you put it is very realistic: that this is an important thing to do if you care about writing.

LE GUIN: The word craft these days has this sort of funny, twee sound, like some little artisan putting the yeast in his handcrafted bread. Craft is how you do something well—anything. You can do anything with craft or with skill, or without it. Writing an English sentence takes a good deal of craft and skill. Writing a good English sentence takes a lot more of it.

SICHA: In the publishing industry, people tend to talk more about book proposals than books.

LE GUIN: Now, you see, here’s where I’m really different from almost all the professional writers I know: I never sell a proposal. I’ve never done it. I’ve forbidden my agents to do it. I write on spec and I turn in a finished manuscript. Once or twice, when Virginia Kidd was my agent, she made a three-book deal, and so she had me committed to writing a book I hadn’t written yet. I was absolutely miserable. I could barely forgive her. Somehow I managed to do it, but I just said, “Virginia, never sell anything again that I haven’t written or you haven’t seen.” She understood. People look at me with round eyes when I tell them that that’s how I work. They go, “How did you ever get going?” Then I have to confess: I wrote seriously for ten years before I sold anything.

SICHA: I mean, that is how that is done.

LE GUIN: You have to have some kind of other work to keep you going or be married to a spouse who can help you put the peanut butter on the bread.

SICHA: I meet a lot of people in their twenties, and they’re concerned. They want to get published, and I think, “Well, hopefully you’re going to live a little while. Don’t walk in front of any trucks.”

LE GUIN: I don’t think most people write very good narrative prose until they’re in their later twenties. Writing is a slow art. Music can be such a fast and early art. A good musician can be just terrific at 16. But how many writers are there … I mean, even Keats is still blundering around at 16. By his early twenties, of course, he’s writing immortal poetry, but there aren’t a lot of Keatses, really. There’s where you get “gift” to a degree that it’s kind of like a miracle. You can’t use the Keatses to talk about writing as a craft or an art or a practice or a profession. The geniuses—they’re off there, doing their lovely thing.

SICHA: They mess up the scale for the rest of us.

LE GUIN: That’s okay. You just have to realize you’re not going to get there, but so what? You can still do beautiful work.

SICHA: There’s room for plenty of people.

LE GUIN: Right. And there’s lots of room for just—I hate to say hack writing—I guess ordinary storytelling is really what I mean. There’s always room for another story. There’s always room for another tune, right? Nobody can write too many tunes. So if you have stories to tell and can tell them competently, then somebody will want to hear it if you tell it well at all. To believe that there is somebody who wants to hear that story is the kind of confidence a writer has to have when they’re in the period of learning their craft and not selling stuff and not really knowing what they’re doing. It’s like being adolescent for years and years after your adolescence.

SICHA: Did you sit down and write today?

LE GUIN: I never had a schedule like that. If I was working on a novel, I probably would have worked from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. or so, because the novel was going and I was there to do it. But I’m not really writing very much now. I don’t seem to be able to write stories—I know I can’t write a novel, because I haven’t got the physical energy. It takes huge energy to write a serious novel. Lavinia [2008] was, as far as I can see, probably it. But sometimes a story comes along. I don’t sit down and write every morning, I am just more in my office at my computer. And if something is there to be written, then I will do it. And poetry comes when it wants to … There’s a sort of readiness, I think, that is part of a professional writer’s equipment. Some little corner of them is always ready and listening for the incoming story or the incoming poem or the incoming idea.

SICHA: You allude to that in the latest postscript to The Left Hand of Darkness, when you say that you would hear things—that you would listen. And you say this about characters too, that the characters come and they tell you what’s happening. You said something along those lines when you returned to Earthsea, too.

LE GUIN: It is a state of openness and readiness that runs all through my practice of writing. That, I suppose, is one reason why I’m simply unwilling to commit myself to writing a book that isn’t written yet. To me, that sort of shuts doors. I have to write this book, but I haven’t written it yet. I can’t be in this state of complete readiness for whatever signal comes in from wherever if I have a project that has to be of a certain kind. Does that make sense?

SICHA: Unfortunately, yes.

LE GUIN: This is true of me. This is simply not true of many writers. I’m at one end of a spectrum here.

SICHA: Some of us simply can’t take orders.

LE GUIN: I believe most of the editors I’ve worked with would say that I’m pretty reasonable. But they’re not giving orders; they’re collaborating. A good editor does not say, “Cut that!” Good editors collaborate with a writer. They say, “You know, that isn’t really clear, is it?” And you say, “Well, no. Hell, it isn’t.” I’m not a sort of willful loner in that sense. I have, after all, had a long time to learn. I started writing when I was 5 and I’m 85. I have learned how I work best, and that is something that, if you’re going to be a professional writer, you should be noticing: under what circumstances you work at your best, and to not get yourself cornered into writing in a way that doesn’t let you do your best.

SICHA: You have to find that spot for yourself.

LE GUIN: And there will be one. Writing is a broad field with all kinds of outlets and publications and publishers and readers. There will be somewhere where you fit. But don’t let them crowd you into a place where you don’t belong or think you have to do it a certain way that isn’t quite natural to you.

SICHA: I’m selfishly sad but also impressed that you feel like you don’t have a novel that you can tackle, that you don’t have the energy for it.

LE GUIN: It does not make me happy. And I don’t like saying it. I think writing a novel that’s going well is about the best kind of work I ever did. And the most satisfying. But I’m just glad now that I can sort of keep going with what I do.

SICHA: The blog [which Le Guin keeps on her site and at Book View Café] is such a good form for you!

LE GUIN: It’s the only place I do feedback. The input is fascinating. I don’t often answer it, but it’s interesting to see what people get interested in, what excites people.

SICHA: It’s like you have a little crowd, but they’re just outside, so they don’t have to be in your house.

LE GUIN: I did that introversion/extroversion test once long ago, and I was just off the charts on introvert. I was slightly inhuman. It was sort of scary.

SICHA: But you didn’t get zero on empathy.

LE GUIN: Oh no! That was never the problem.

SICHA: You just need some time to be alone.

LE GUIN: I just need solitude.

CHOIRE SICHA IS A NOVELIST AND CO-FOUNDER OF THE AWL.