Karan Mahajan Reinterprets Home

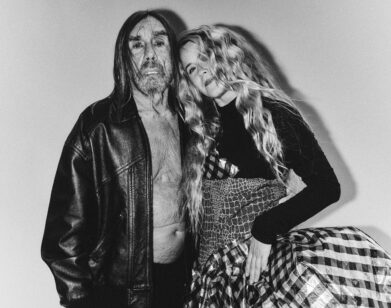

ABOVE: KARAN MAHAJAN. PHOTO COURTESY OF MOLLY WINTERS.

When a bomb explodes in a Delhi marketplace, the ramifications are widespread and devastating. The Hindu Khurana family learns that their two sons, Tushar and Nakul, have been killed while their Muslim friend Mansoor was spared. By embracing a constantly shifting point of view over two decades, Karan Mahajan explores the many tangents of pain in his deftly poignant second novel The Association Of Small Bombs (Viking).

Born in Stamford, Connecticut, and raised in New Delhi, India, Mahajan studied English and economics at Stanford University and published his first novel, Family Planning, in 2008. In The Association Of Small Bombs, the now 31-year-old author unwraps the psyches of all those involved in the tragedy—from the bombers to the bombed. It is this even-handedness that makes the novel shine; Mahajan allows himself to emotionally disengage from a charged subject matter and let the story take the spotlight. Also under the microscope is India itself, in particular Delhi with its swarming pollution, corruption and prejudice.

JEFF VASISHTA: The structure of this is so unique. In many respects it reflects the fall out of a bomb blast. What inspired it?

KARAN MAHAJAN: The structure was organic. I knew I wanted to stay close to the epicenter, the heat-source of the explosion, to not sprawl too far, and I alighted upon a set of characters who would think about the blast constantly, but in different ways. Think of it as a piece of music, with each perspective as a variation on a theme.

VASISHTA: Sociologically this is quite dense. There’s a lot of knowledge about Indian, Kashmiri, and Pakistani terrorism, how people dress, agricultural fairs in rural India compared to urban India, terrorist cells, etc. How did you research this?

MAHAJAN: Tons of reading and travel and conversation. The book brings together a lifetime’s worth of knowledge about India, along with knowledge I gleaned traveling around India for a year and a half for a job I had that was based in Bangalore. This job took me to small towns; it was my mandate to interview people and hear their life-stories. Along the way I picked up a lot of odd, incidental details. And then there was my reading of the news and of texts related to terror in India, many of which remain unexplored. I also snooped around the courts in Delhi, a real education for a writer.

VASISHTA: There’s a certain sense in this that people wear their identities. Shockie is initially muscular while Malik is weak. You also say of Vikas, “You could see misfortune imprinted on people’s faces before it hit them.” His cousin, Mukesh, had always known that Vikas “the academic star of the family would be a failure.” Ayub is fair and delicate and seems easily led. It works well in literature. It was a ploy often used by Dickens too. Do you think there’s an element of truth about that in real life?

MAHAJAN: Literature has become too psychological. We discount the physical, when in fact much of life is physical. People’s personalities are partly formed by, or in response to, how they take up space; the physical mask has some relation, howsoever obscure, to the mental work happening underneath. I tend to see my characters from inside and outside at once; this is a technique I use to retain a slight distance. It means my characters can act in unexpected ways on two axes: physical and mental. It isn’t just, “I thought this and then I did this,” which is the technique of the modern psychological novel.

VASISHTA: One of the most moving scenes is when you describe how close the Khuranas were as a family, always hugging one another, so that we really feel the parents’ anguish. Did you know parents who had lost children from terrorism? Were their characters based on anyone in particular?

MAHAJAN: I don’t know anyone personally who’s lost children in a terrorist attack, but I know people who’ve suffered extreme trauma, and I conducted a lot of research on the ways survivors in India cope in a fairly hostile, indifferent environment, where the press may forget about a blast after a few days and the government might infinitely postpone hearings and no one respects your privacy. But most of the work was imaginative. I had thought about this family for so long that I felt I was writing reality.

VASISHTA: The novel foregrounds a lot of the internal prejudices in India. What’s most noticeable is the intense Muslim prejudice. Is that something that is very obvious in everyday Indian life now?

MAJAHAN: It is—at least in the circles I know in India: the milieu of Punjabi businesspeople. Obviously this group isn’t a monolith, but you’d be horrified to hear the things people have to say about all sorts of outsiders: Africans, (Indian) north-easterners, Tibetans—anyone who comes into their crosshairs. Muslims remain the most convenient target for prejudice in a city like Delhi, which is far more ghettoized than Bombay or Bangalore, for example.

VASISHTA: Yes and generally Delhi gets a pretty bad rap in this novel, particularly the dirt, pollution and corruption. How do you feel about your home city? Is it a love/hate relationship?

MAJAJAN: Despite my critical take on the city, I love Delhi, on the whole—love its monuments, love how easily graspable the city’s turbulent history is. The negative things I write about are considered normal here.

VASISHTA: Pain, physical and emotional, is a big part of the novel, how people endure it for long periods of time. Many of your main characters are living in abject pain. Did you set out with this as a central theme?

MAHAJAN: Yes. The novel came out of a connection I made between psychosomatic illness, which persists after the cause has been withdrawn, and terrorism, which leaves a smear of fear long after the attack is over. I didn’t know how I’d combine them, but Mansoor’s injury and recovery and relapse provided a way in. I also feel that novels tend to use a filmic shorthand for things like mourning and pain—we see characters suffering catastrophic loss, then the novelist cuts and years pass and we’re meant to impute the character’s pain. But what about the days and months and years lost to depression? How to represent this sticky state accurately without making it boring to read? It was the central challenge of the novel. At first, I only had the Khuranas and it was impossible to move forward through the swamps of their grief. Placing their depression within a network opened the book up.

VASISHTA: You were born in Connecticut but grew up in Delhi. Because you had an American citizenship, did you always know that you would come back to live one day? Could you imagine living in India on a full-time basis again?

MAHAJAN: No. I never imagined coming back to the U.S. The U.S. citizenship was a fun badge of difference to possess growing up in India, but I imagined I’d go to Delhi University or IIT. The idea of going to the U.S. was only introduced in class 11 by my mother and then, too, finding a way to take the SAT, pursuing applications, writing essays, was very foreign. When I came to the U.S., I imagined I’d stay for college and return soon after graduating to India. As a result, my life in the U.S. has always felt like a mistake, like something contingent, something which isn’t real, which could end anytime. But each time I’ve moved back to India—to Delhi, in 2007, to Bangalore, in 2011—I’ve been thwarted, for financial or personal reasons. I’ve made a sort of peace with the fact that I’ll always live between both places.

VASISHTA: You have been fairly well entrenched in the U.S. literary world from Stanford to Fort Greene in New York and now Austin, Texas. What did you get from each city as a writer and why the desire to move on?

MAHAJAN: I’ve known the literary scene, yes, but my time in these cities has been defined by jobs. In San Francisco, I worked as an editor at an indie publishing house; in Brooklyn, I worked for the NYC government as a long-term economic and urban planning consultant; in Bangalore, I was employed by a tech billionaire who wanted to put together a history of entrepreneurship in India. Coming to Austin for the Michener Center (University of Texas’ MFA Program) was the first time I committed to the literary life—when I accepted that, yes, despite the difficulties and roadblocks, I was primarily a writer. It’s amazing to me in retrospect that I wrote as much as I did with full-time jobs. Each city gave me a new distance from—and a new way of looking at—India. I’m grateful for the movement. I feel as if I’ve crammed several lives into one.

THE ASSOCIATION OF SMALL BOMBS COMES OUT TOMORROW, MARCH 22.