Giovanna CAU

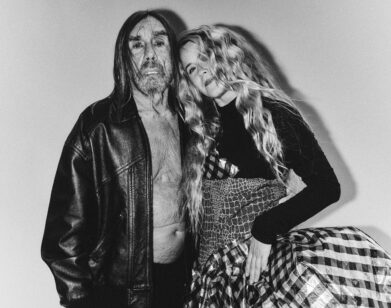

Marcello and I were paparazzi’d on our way to L.A. to see Garbo, via Paris and New York. Giovanna Cau

With a cigarette between her fingers and an ashtray propped on her lap next to her gray cat Salomè, Giovanna Cau sits near the lush, riad-style courtyard in her house in Rome. The legendary Italian attorney’s feisty temperament and intelligence have granted her a life alongside Italy’s most prominent artists and intellectuals. The friends and clients, for whom she oversaw legal, artistic, and personal affairs, include Marcello Mastroianni, Federico Fellini, Sophia Loren, Italo Calvino, Alberto Moravia, and Ettore Scola. As a lawyer, Cau fought for actors, directors, and writers—pushing against censorship and ensuring that they possessed full rights to their work. But her influence went far beyond the contract. In fact, her Rome offices functioned as something of a salon for her friends, where political, artistic, and cultural ideas were openly exchanged—all within Cau’s earshot—and often augmented by her own opinions. Many of the iconic films of Italy’s golden age, including 1960’s La Dolce Vita and 1977’s Una Giornata Particolare (U.S. title, A Special Day), germinated inside her offices. Artists felt at home there, and since she had so many clients, it was easy for her to foster connections between people.

This resilient, tenacious, unapologetic 91-year-old chain-smoker was recently described by director Marco Spagnoli—who made the 2011 documentary Diversamente Giovane (Differently Young) about her—as a “miracle in longevity, intelligence, and vision.” Cau lives in a gorgeous, eccentric house in the Trastevere neighborhood, where she has recently relocated her firm with all of its archives. Her desks are piled with pastel-colored folders with handwritten names of her still-active clients, including the Moravia and Mastroianni estates. Her Liberty-style den is teeming with Moroccan and art nouveau influences, film-world memorabilia, autographed books, Lalique glass treasures, and romantic gilt jewel boxes. Her bedroom, dominated by a porcelain bathtub, is a secret boudoir. Her late partner, the progressive psychiatrist Emilio Benincasa Stagni, was so marveled by her odalisque-themed décor that the day he moved in with her in 1960, he proclaimed, “I am not sleeping in this prostitute’s den!” He transferred his belongings into the bedroom next to hers. They never slept in the same bed, but Cau wouldn’t compromise—not in her personal nor professional life.

Cau’s adventure spans Italy’s explosive postwar years, during which she appeared in the forefront of the country’s most significant political and cultural battles. She became a Communist party supporter early in her life. In 1946, when she was only in her early twenties, she also organized the first feminist group in the country to fight for and obtain women’s right to vote. In the following years, she maintained her politically fervent attitude, championing the rights of divorce and abortion and even the rights of those with Down syndrome. Last July, in the “prostitute’s den,” I met a tiny, fierce lady with bright, alert eyes who, one slim cigarette after another, talked about an entire century—which didn’t feel so far away.

CHIARA BARZINI: You’ve witnessed an important piece of our country’s history, both in terms of politics and what you did to safeguard the rights of artists and writers. Everyone knows your name in Italy. Now it seems like you should be introduced to the rest of the world—especially the United States.

GIOVANNA CAU: Great. I am a big fan of Obama.

BARZINI: Really?

CAU: Oh yes. I’d like to lie on the ground and have him walk over me.

BARZINI: [laughs] In Marco Spagnoli’s recent documentary about you, director Giuliano Montaldo asks a very important question: What came first in Italy, cinema or Giovanna Cau? How would you answer?

CAU: Well, I was born in Rome on March 11, 1923. Because of my age, I’ve become a piece of this country’s history, but it’s also true that a certain strand of Italy’s film history has passed though me.

BARZINI: The great commedia all’italiana director Ettore Scola called your office a “dating service” for film people.

CAU: That may be true, but I surely haven’t only dealt with film people. As a lawyer, I also fought against evictions, or worked on leases—the unglamorous side of the business, too. What applies to me now is another phrase coined by Ettore Scola, who is still a very dear friend and a client to this day: “We are commemoration prisoners.” Because of our memories, because of our age, and because of what people like he and I have been through, we are now forced to commemorate and remember things for everyone else.

BARZINI: In 1949, you were invited by Alberto Cortina to become one of the first female lawyers in the country. Do you remember what [Marcello] Mastroianni said to Cortina when he was told a woman would be joining the firm that represented him?

CAU: “Let’s just hope she’s hot!” is what Mastroianni said. Alatri, Cortina, Cau was the name of our firm. I still have our first signed document framed—part handwritten, part typed. It’s very dear to me. When Alberto told Andrea [Alatri], whom I used to call “the dwarf,” that he’d be splitting everything three ways, Alatri was horrified. “Are you crazy? What’s running through your head?” But when Alberto mentioned my name, Alatri accepted. His “yes” determined my entire life. I am indebted to him forever.

BARZINI: Your law office was a renowned spot for a certain kind of elite conviviality. There are many stories about food, alcohol, and cigarettes being consumed there. You are an unrepentant smoker and Mastroianni was an avid whiskey drinker who always made sure to bring a bottle if you ran out.

CAU: All of that was mostly thanks to Marcello. He was a client, but also a very dear friend. He’d spend entire days in my office. When he wasn’t working and didn’t know what to do in his spare time, he’d wake up, head downtown, and sit on my couch while I worked. He went on whiskey runs and picked up the phone like a secretary. He poured us drinks. He loved to eat and drink.

BARZINI: You’ve mentioned that Mastroianni, whom the world knew as a relentless tombeur de femmes, was actually a timid and often self-conscious man.

CAU: There were a lot of contradictions between Marcello’s public persona and who he was in private. For example, he had a completely negative opinion of his body. He complained that his legs were too skinny, which they were. I never saw him, not even in the middle of summer, without a pair of long trousers on. He also complained that his shoulders were too big. He didn’t think of himself as beautiful in any way. The fact that Italy chose to incarnate him as a model of beauty stupefied him. Another surprising detail is that I’d never seen Marcello truly in love with a woman. I called him “the man who couldn’t love.” He was capable of enormous amounts of affection. He respected the women who were close to him, but never once fell in love. I never saw him lose his mind or be wild about a woman. Never. And this includes all the great women of his life.

BARZINI: So what was his version of falling in love?

CAU: Well, like I said, there was no real falling in love. But like all men, he didn’t realize he wanted something until after it was gone. For example, if a woman he was seeing would finally—and rightfully, in my opinion—cheat on him, suddenly his senses would awaken. But that’s all men, isn’t it? That’s the moment when they finally get pissed.

BARZINI: I don’t know if you’ve read Hollywood Babylon by Kenneth Anger, but what I always found surprising about it is its portrait of the film world’s moral structure from the 1900s to the 1950s. They were much more permissive. Promiscuity was a given. I feel like you’ve lived next to some very daring men, like Fellini and Mastroianni. Today’s culture would probably judge them for their lifestyles, but you stuck next to them without ever second-guessing them.

CAU: Well, of course. For example, Mastroianni never left his first wife, Flora, even when he had other out-in-the-open relationships. When Catherine Deneuve, whom we nicknamed Caterinetta amongst ourselves, told Marcello she was pregnant with his daughter [Chiara], Marcello ran to me, desperate. “Oh my God, what’s going on?” he screamed. “We have to go and see Flora.”

BARZINI: We? So it was a given that if ever there was an emergency, the two of you had to be a team?

CAU: We, of course. I was a permanent sidekick. From his first meeting with Greta Garbo onward, I was always by his side in important, decisive moments.

BARZINI: So what happened when Mastroianni told his wife Flora that he was having a child with Catherine Deneuve?

CAU: Flora lived in their villa close to the Ardeatine walls outside Rome. When we got there, Marcello started talking in a very roundabout way before spilling the beans: “How are you, dear Floretta? What’s going on today?” We were sitting in the living room in front of a table filled with precious Lalique jewels and glass creations. I had bought them myself as gifts and knew quite well how valuable they were. Marcello went on mumbling things like “Well, honey, you know this thing happened …” And I saw Flora take the most precious Lalique piece off the table and lift it menacingly into the air. I thought to myself, “Oh God, she’s actually going to do it. She’s going to smash it on the table.” But since Flora was another crazy character—quite fun, but definitely nuts like the rest of us—the Lalique remained in her hand in midair as she asked, “Girl or boy?” Marcello answered, “Girl.” And Flora calmly set the Lalique back on the table, composed. She couldn’t have handled another male Mastroianni, but a girl was okay for some reason. So Flora calmed down and the Lalique survived only because Deneuve was pregnant with a girl.

BARZINI: And what about the meeting with Greta Garbo? How did you figure as a sidekick then?

CAU: Marcello and I were paparazzi’d on our way to L.A. to see Garbo, via Paris and New York. It’s one of the few documents I have of us together. I hated being photographed and never wanted to go on red carpets, even though they always asked me to. My place was behind the scenes. I wasn’t a diva. I preferred to look at life from the outside. So it was the ’50s. I wore a beautiful fur coat and took off with Marcello. Garbo had called him in Rome and asked to meet him. He, of course, spoke very little English and immediately said, “You’re coming with me.” We met her in our hotel in Los Angeles. This incredibly beautiful, tall, imperious woman showed up in front of me. She was truly intelligent and had retired from the film world already. I said hello shyly. After meeting her, we didn’t do anything else in L.A. The meeting alone made the whole trip worthwhile. We took an airplane and flew back to Rome. It’s one of the most beautiful memories of my life. Not everyone has a chance to meet Greta Garbo! I was so in awe of her that I recently had my assistant search online for her film Queen Christina [1933]. I cherish that rare DVD like a precious keepsake now.

BARZINI: You and Mastroianni were best friends and confidantes. It’s rare to imagine actors as good listeners.

CAU: He was a generous listener because we were great friends. He confided in me completely. He told me things he didn’t tell anyone else, and so did I. I lived with my partner Emilio for years without telling him the things I told Marcello. We spoke about sensations, emotions, and things that couldn’t even be voiced out loud at the time. There was an incredible intimacy, one I’ve never had with anyone else in my life and will never have again.

BARZINI: This sounds like a great love story to me.

CAU: No, not a love story. I’ve never been in love with Marcello. I wasn’t even attracted to him physically. I admired him. I followed him and supported him, but nothing ever clicked. In this rare picture I have of Marcello, my partner Emilio, and I at Maxim’s on New Year’s 1970, it’s Emilio who looks to me like the real actor. We were there because Marcello was trying to get over his fiasco with Faye Dunaway. That same night, two Italians took us to Régine’s where Caterinetta was. Emilio, who spoke great English and a little bit of French, was sent forth to collect her. That was Marcello’s first encounter with her, but I remember feeling terribly bored by the whole charade of these crazy Italian men. I left early.

BARZINI: What was the fiasco with Faye Dunaway?

CAU: Marcello invited her to spend Christmas in Rome with him, failing to inform her he already had a wife and family. I think he didn’t believe she’d actually show up. Faye landed in Rome on December 23rd, and Marcello freaked out because of course he couldn’t not spend Christmas with his family. At the same time, my partner Emilio had his own family to spend Christmas with because divorce wasn’t legal in Italy yet, so technically he was still married and had to celebrate with his wife and kids.

BARZINI: What a mess!

CAU: Marcello asked Faye to spend Christmas with Emilio because he was the one who spoke English. Marcello called me continuously to get updates on Faye. I then had to call Emilio’s house to get the latest from him. I remember urging Marcello on a bit by telling him, “Wake up, you’ve left Faye Dunaway alone with a handsome man who speaks great English. I don’t want to know what can happen over there!”

BARZINI: You were a kind of middle woman in his affairs and getting your own partner involved, too …

CAU: Oh yes, I always helped everyone on these occasions. It was a second job.

BARZINI: What do you think Mastroianni and Fellini would say about how politically correct the arts have become?

CAU: They’d fit right in. They were both great liars! One day Fellini came to my office and announced, “Giovanna, listen up: we’re going to call Giulietta [Masina, Fellini’s wife] right now. We’re going to get on the phone and tell her we have a very important dinner with a producer.” Of course, this wasn’t true. We didn’t have anything to do, but Federico got on the phone, and with Marcello’s identical tone of voice when he had to speak to his own wife, started: “Giulietta? Giuliettina, baby … Let me pass you to Giovanna. She has something to say to you.” I got on the phone with Giulietta and covered for Federico. “Hello. Of course we have a horrible dinner date with a flaky producer tonight. Nothing will come of it, surely, but we have to attend. I will let you know as soon as we’re done so that Federico can come home.” The moment we hang up the phone, Federico rushed to the secretaries’ room and announced, “If anyone, anyone calls, you tell them Giovanna is with me. She is not available for anybody!” You want to know what Federico was up to? He went on his infamous “sepulcher tour.” He was crazy about these three old ladies, ex “quickies” of his, and loved to sleep with the three of them in a row. I still remember their nicknames. One was German, and we called her “The Condor.” I remember looking at these three old ladies with the eyes of youth, thinking they were old and nasty!

BARZINI: Do you think Giulietta ever suspected you were covering up for him?

CAU: No, because he was good … And I was even better.

BARZINI: You were never shocked to hear such stories by these men?

CAU: Absolutely not. I was in on their secrets, so I couldn’t have been shocked by them. Of course, what none of these people realized was that their so-called secrets—I called them Pulcinella secrets—were actually no secrets at all to the rest of the world. They thought they were hiding them, but everyone knew.

BARZINI: What is the quality about yourself that you think made it possible for people like Fellini and Mastroianni to entrust you with their private affairs?

CAU: Well, they were great liars, and I was great at keeping secrets. I didn’t communicate with anyone, and they knew it. They’d tell me, “Hush, be quiet!” and I followed orders. I never uttered a word about things, but with my age now, I’ve completely lost all reservations. In more ways than one. I was never in front of the camera, for example, but now I’ve been in films and documentaries.

BARZINI: Spagnoli’s documentary about you premiered at the Rome Film Festival in 2011. You were honored with the Italian Golden Globe and Silver Ribbon awards, and Spagnoli won a special prize assigned by the Sindacato Nazionale Giornalisti Cinematografici Italiani [Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists]. In many ways, it broke your privacy after 88 years of living behind the scenes. What effect did that have on you?

CAU: It was a beautiful documentary. We spent a lot of time together. It’s strange to me that so many people want to have me in front of the camera now. Again, to quote Scola: “I am a commemoration prisoner!” But I’m willing to do that as long as I’m here. In terms of losing all reservation, I’m also playing a role in the next film by [director] Gianni Di Gregorio. The story takes place in an apartment building, and I play the part of a woman who doesn’t want people to smoke inside. I would have never dreamed of doing something like that in my youth. Backstage, of course, they interview the real me: a chain-smoker. Everything has changed now. The world has changed. It surprises me to be on the forefront. I’ve lost all dignity! I give interviews! I make movies! I’m amazed at myself.

BARZINI: You’re known for your dry humor, and that’s certainly a quality you shared with Mastroianni. How important was irony and wit in your relationship with him?

CAU: Once Marcello was shooting a film in Spoleto and took his mother Ida with him so she wouldn’t stay alone in Rome. When I got there, Ida asked me, “Are you Brigitte Bardot?” Marcello cracked up and intervened: “Mom, this is Giovanna Cau, my lawyer!” And his mother replied, “I don’t understand why anyone would waste a body like that on being a lawyer.” Well, I am forever indebted to her. So much so that when she died, I found the spot for the Mastroianni family grave under a mimosa tree right across from my own family grave in the beautiful Verano cemetery of Rome. Marcello asked me why I was always bringing flowers to Mamma Ida’s grave. Even after he died, I kept doing it. Sometimes I’d find cemetery visitors screaming at me about how unkempt and minimal the Mastroianni grave was. No photo, no frills. “Are you a relative? You should do something about this,” they’d say. “Yes,” I answered. “Sorry but that’s the kind of man he was. He didn’t care about those things.” Of course, my flowers were never for Marcello, but only for his mother Ida—the person who mistook me for Brigitte Bardot. You know what Marcello would say if I told him I was bringing flowers to his grave? “Go get locked up in an insane asylum!” That’s the kind of cynical humor he had.

BARZINI: How was the relationship between Fellini and Mastroianni?

CAU: Fantastic. I have many photos of them together to prove it … My men.

BARZINI: What about your women?

CAU: I had fewer female clients. I don’t know why. It was always the men who chose me. And the ones whose secrets I had to hold. I represented Sophia Loren. She was jailed in Caserta for 17 days.

BARZINI: That’s right, in 1982. She had already won her Oscar and had been sentenced for tax evasion. She was in Switzerland, but she went back to Italy and served her sentence. The area outside the jail turned into a pilgrimage site. People opened stands in her honor, selling her pictures. They even sang serenades beneath her window! Were you in charge of her legal affairs at that time?

CAU: She was invaded by paparazzi and journalists, and it was such a big deal because the head of state didn’t grant her special treatment. I went there to help her out, but I knew she had to serve her time because that was the only way for her to get her freedom back. I went there for support. I’m not her lawyer anymore, though.

BARZINI: Is it true that Sophia Loren was in love with Mastroianni, but they never got together because of scheduling conflicts?

CAU: Well, at the time when things could have happened between them, Marcello had Flora on one hand and [actress] Mirella Gagliardi on the other. He couldn’t add Sophia Loren to the mix. When things finally dwindled down with Gagliardi, Marcello suddenly woke up and said, “I could have had Sophia!” But the problem was Sophia went to bed at 7 p.m. because she needed her beauty sleep, and Marcello was a nocturnal creature. Of course, he was never in love with Sophia Loren, but he did have a reoccurring dream about her: a great king-size bed with Loren’s husband, the producer Carlo Ponti, in the middle, Marcello on one side and Sophia on the other. Makes sense, of course! He’d been forced to do Carlo’s films with Sophia even if he didn’t want to.

BARZINI: What about Monica Vitti, your other female client?

CAU: She was a great actress, but a very difficult person. I am not in contact with her at the moment because she is very sick. Not a generous woman, I have to say. I don’t see her much.

BARZINI: And what about all your writer clients?

CAU: Alberto Moravia, Italo Calvino, Natalia Ginzburg, and Vasco Pratolini: the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

BARZINI: I was shocked to hear that Calvino wasn’t allowed to have his own writing room at home. From Virginia Woolf onward, I thought every writer had a right to have a room of one’s own.

CAU: Calvino’s wife never allowed it. Not in their beach house in Roccamare, nor in their house in Rome. He was bound to do his writing in the midst of family life and chaos. We had a great relationship. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that his only daughter’s name is Giovanna. I loved his book dedications to me: “To Giovanna Cau, another book that won’t be turned into a movie.” He always said it would be impossible to try to make films out of his books, though he hoped it would happen because that’s where the money was.

BARZINI: I thought it was the opposite of that. I thought nobody has ever been granted the rights to make a film out of a Calvino book.

CAU: That’s news to me, but I am not in charge of his estate any longer. Anyway, he was very down to earth. The first thing he’d asked for when he flew into Rome from Paris was for me to make him artichokes. He loved artichokes.

BARZINI: Food keeps coming into play in the memories of these artists and intellectuals. I know Mastroianni was obsessed with basil, and when you were apart, he always needed to know what you ate for dinner.

CAU: Oh yes. Once he was in the United States, shooting a film in Chicago with Scola, and he got to a payphone with a pocket full of coins. He called from the film set all the way to Rome because he wanted to know what restaurant we’d gone to the previous night and what we’d ordered.

BARZINI: I want to force you to be a “commemoration prisoner” a little bit longer and rehash an incredible detail in your life: you were part of the very first committee of women to battle for women’s right to vote in Italy.

CAU: Yes, out of all the things in my life, that is what I am most proud of. It’s my greatest success. Women did not vote in Italy until 1946. A good friend and I put together a group of women to protest this. I was very young, just a girl. We went to the Viminale [home of the Ministry of the Interior] and spoke to the chair of the ministry board. Also in the group was the wife of Palmiro Togliatti [leader of Italy’s Communist Party]. Thanks to our initiative, we got the bureaucracy rolling on giving women the right to vote. I have to thank my father for this. He was in Geneva at the League of Nations, and women voted there. He thought it was absurd that women didn’t vote in his country yet. I also fought in favor of divorce, abortion, and against all film censorship. I was very politically active and organized myself in small but combative groups. My life’s true pride is to have succeeded in these causes. They weren’t easy battles to undertake in Italy at that time. Things are easier now.

BARZINI: Which one of the films you’ve represented do you hold dearest to your heart?

CAU: Ettore Scola’s Una Giornata Particolare with Marcello and Sophia Loren. It’s my favorite film because it involves many people I loved very much. I loved Marcello’s unprecedented performance as a gay man. He had incredible mannerisms and moved very well. I also loved it because it gave Scola so much success.

BARZINI: What are your favorite objects given to you from your clients?

CAU: I have many, including Moravia’s walking cane and one of Fellini’s scarves. His note to me read: “Dear Giovanna, A great hug to you with my warm, warm scarf.” He always wore great scarves and gave me one as a keepsake.

BARZINI: Do you have any regrets?

CAU: Not at all. I had a very full life, with pains and losses, of course. I lost all the people I was closest to: my partner, my father, and my best friends, but I can’t complain. I am 91 years old and I am still here at my desk. Work is a great thing. This is something my father taught me. He didn’t want me to grow up to be somebody’s wife. I was the first of seven children. My father was everything to me. Unlike my mother—I didn’t have a special affinity with her. She never pushed me to work and was not the wife a man like him should have had. She’d go off to the neighbor’s terrace and leave us alone. We poured talcum powder in the hallways and camped out under the long kitchen table, which we called “our boat.” We set up a net on top of the table to play ping-pong. But today’s consumerism has changed things. I think children are much less creative now.

BARZINI: So in a house with six siblings and an absent mother, did you have to babysit a lot?

CAU: Oh, God no. I didn’t take care of the kids. I took care of the interior decoration of the house. I wanted to be an architect, so I curated that aspect of things. In the middle of the chaos, I moved things around and rearranged everything to find my order.

BARZINI: Do you have any advice for anyone starting to make movies today?

CAU: To always care for the writing part first. Every good film project starts with good writing. If you have a good script, everything else follows. Writing is crucial.

CHIARA BARZINI IS A ROME-BASED WRITER OF FICTION AND JOURNALISM.