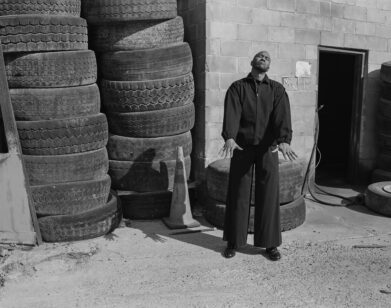

Daniel Riley and the Other Side of Paradise

PHOTO COURTESY OF FRED WOODWARD.

Daniel Riley’s debut novel, Fly Me (Little Brown), is a stunning and dangerous ride set in the skies of 1972. Suzy Whitman and her older sister have moved out to Sela del Mar, a sleepy California beach town, to become a stewardesses. At first, Suzy is half-seduced by, half-suspicious of her new life and a job that promises adventure, but is also stifling in its exploitation of her gender. But Suzy—a race car driver and recent college graduate—is not your typical “stew” and Sela del Mar’s sunny façade hides a darker side. Stuck between escaping her past and not knowing her future, Suzy becomes in involved in drug smuggling, with risky runs made more so by the threat of skyjackings.

Throughout Fly Me, Riley paints a seductive and psychologically intense picture of the times, combining political change, sex, drugs, and a painful coming of age with the idyllic backdrop of a Pacific paradise. We spoke with the author about the complicated lure of California beaches, anxiety of dislocation, skyjackings, and the feeling of freedom flying gives us all.

ROYAL YOUNG: California, 1972. Playboy is moving out there, so is Jim Jones. There’s skateboarding and surfing. Where did that world come from for you? What’s the fascination?

DANIEL RILEY: I was born in 1986 in Southern California, so my beach towns are very ’90s and early 2000s, but my mom and her sisters grew up in Manhattan Beach during that time. For my parents and their generation, there was a different energy and heat. As a kid, I thought that’s when all the stories happened. When I started thinking about this book about two sisters and the airline industry—flight attendants and skyjacking—I thought I could yoke these two things together. So much of that detail still hangs in the air. There’s been a lot of change, but the social contract when you move there is that you want that feeling. It’s like an Instagram filter. The town Sela del Mar in the book is a lot of beach towns from Santa Barbara down to San Diego. I wanted to get under the layers of familiarity with Southern California to get at the psychology that animates both insiders and outsiders. What a place can do to somebody’s brain if you’re born there and told it’s heaven on Earth and there’s no reason to ever leave, or if you’re an outsider being fed that line and either totally believe it or are deeply resistant to that spell.

YOUNG: Culturally, we’ve bought into the idea of little pieces of heaven where nothing really happens and every day is sunny. Even if that was the case, which I don’t think it is, what does that do to you?

RILEY: Right. I think it’s less the case now, of feeling like you’re at a giant remove from places where things happen. There’s a weird and deliberately and strange way news works in the book, where major events happen through this gauze. Like in Sela del Mar in the book, you get a free drink if you can prove you didn’t vote on election day. Life happens elsewhere. The town can suck you in. These airplanes allow you to burst out of that.

YOUNG: Today, as you said, there would be a Sela del mar Instagram filter, so you would definitely be more connected to the world in that way. With Suzy, who has this specific personality, the question of “why leave?” becomes a challenge for her.

RILEY: [laughs] Exactly. The place slowly works over her and seduces her, but she has this anxiety of dislocation and right place, right time. She feels, “How do I know where I’m supposed to be?” But what happens when you are forced over the edge? That idea that things better work here, because here’s where we run out of continent.

YOUNG: It’s about flying and escape versus momentum and purpose.

RILEY: Exactly.

YOUNG: So Suzy’s dilemma is a tug of war.

RILEY: Yeah, and it’s about what kind of person could find themselves in that specific tug of war? Suzy is inherently in those forces. She’s interested in race car driving and this constant idea of being stuck in place or speeding away; taking off and landing. For all the forces of the time period and her upbringing that say a young woman can’t do this, she’s actually cut this new path that’s given her more tools and control.

YOUNG: What did it mean being a woman at that time? Sadly, I don’t think a lot has changed.

RILEY: All the women I grew up with—my mom and aunts and friends—made me so interested in the year you were born and how plus or minus a few years could completely recalibrate your opportunities. Suzy, who races cars and has a sense of purpose in an athletic way, misses out of Title Nine. She’s four years late for being able to play a whole different set of sports in high school. She’s a year too early to be accepted to Yale. The airlines had all these completely antiquated ideas about what a woman needs to be as an employee—height, weight and make-up standards, marriage rules. Suzy rejects these ideas. She’s not on the front of women’s lib activism, but she pushes back.

YOUNG: There is a sense of imminent change.

RILEY: Yes, and all personal acts can be political.

YOUNG: There’s a great line in the book where she wonders if she’s going to spend her whole life being afraid of men.

RILEY: As a young woman, at some point, you realize being alone with a man is either going to be a great thing, or it could be a threat to your life—especially in that time period. That’s something I think about a lot as not a young woman, that every moment can feel threatening.

YOUNG: I had no idea skyjacking was such a frequent occurrence.

RILEY: In the late ’60s and early ’70s, it really spiked. At times it was one skyjacking a week. There was real tension between the liberty people feel flying and airlines saying there was no way they could put in any security measures, but it was an increasing threat. There were no metal detectors until January 1973. It was so common that people skyjacked planes to Cuba, that the American government considered building a fake landing strip in the everglades where planes could land and then be surrounded by FBI agents.

YOUNG: What is it about flying? It’s such a miraculous, complicated, scary, wonderful thing.

RILEY: I feel all those feelings. It’s astonishing that it’s possible. It represents in-between living—you’re not in one place or the other. Anything can happen. You can end up anywhere.

FLY ME IS OUT TODAY, JUNE 6.