The Fantes’ Inferno

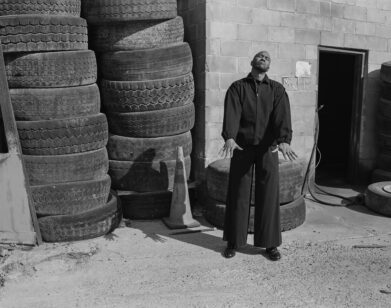

PHOTO COURTESY OF MICHAEL NAPPER

Hollywood may seem scandalous today, but it’s nothing compared to the town it once was. In Fante: A Family’s Legacy of Writing, Drinking and Surviving (Harper Perennial), Dan Fante explores the Los Angeles he grew up in. Raised by John Fante, a disenfranchised author and reluctant player in the movie business, Dan grows up bearing witness to his father’s failed literary career, his intense anger, and his benders with William Faulkner, Bill Saroyan, and other writers thrown into Tinseltown. After becoming a carny and getting inducted into his own shady, sexed-out L.A. world, the younger Fante flees to New York and pursues multiple dead-end careers, inheriting his father’s taste for liquor and losing.

Yet both Fantes are survivors, and as his father’s major literary work Ask The Dust gains recognition later in his life, the son struggles through recovery, 12-step programs and his own writing. The result moving and epic picture of a family torn apart by its own demons and then slowly stitched back together through sickness, sadness, and strength. Five successful novels later, Dan regularly visits Toricella Peligna, his family’s hometown in Abruzzo, Italy, to celebrate his dad’s memory in the town’s annual John Fante Festival. We talked with Dan Fante about dangerous family legacies, growing up in Hollywood’s golden glow, self-destructive artists and how he finally made sense of it all.

ROYAL YOUNG: How did growing up in Hollywood shape your life?

DAN FANTE: Well, my father viewed himself as an outsider. He was a very busy, working Hollywood screenwriter. But John Fante was also sort of a hack and was always pissed off at the studios and always working on some deadline, on some piece of dreck for some producer. That was kind of our day-to-day life. But growing up in Hollywood, every once in awhile some movie star would pop in—Kim Novak, or Will Rogers, Jr. lived nearby. That was fun, but my dad did not consider himself a Hollywood person. He was pretty cynical.

YOUNG: And then on top of that, growing up very much in your own imagination, how did that shape your later life?

FANTE: There was very little father-and-son time, and there was a lot of rage and a lot of intensity, so I didn’t lack for drama. [laughs] So I was kind of on my own. We were from a family of drinkers; my mom wasn’t a big drinker, but my dad was. He was a carouser and loved to gamble, so he would kind of storm in. My mother used to say John Fante had two moods, one was angry and the next was angrier.

YOUNG: What’s the difference between rage that motivates you and rage that destroys you?

FANTE: There’s a fine line. I didn’t know the difference until I was quite a bit older. Rage has to be channeled. I didn’t understand that until I hit bottom with booze, but that rage, that energy has to be put in a place. My father could do it, but I never understood that he could. I thought he was just a crazy writer, who was always pissed off. But he spent a lot of time writing. I didn’t learn until my late thirties that I could do something similar, only I couldn’t pour Seagrams V.O. on it and have it work for me.

YOUNG: Do you think drinking and substance abuse and creativity go hand in hand?

FANTE: [laughs] Substance abuse and suicidal tendencies go hand in hand. I drove a cab in New York for seven years; I have my Ph.D. in cab driving. And what happened was that when I drove, I didn’t drink, and I got very creative. I used to write poetry, I would just pull over if I had an idea and write it down. And for all those years, everything I wrote, I destroyed at the end of the day because it was never good enough. It was all shit until I stopped drinking, and my thoughts became coherent enough and the self-judgment was eliminated enough, that I began to save my poems.

YOUNG: So it’s not so much substance abuse that goes hand in hand with creativity, but maybe it’s a kind of self-destructive impulse.

FANTE: Yeah, I think so. Look, if a normal person is reading this, the metaphor is if you eat ten teaspoons of sugar every two hours, you’re going to have a bit of a personality disorder.

YOUNG: How often is perceived failure a self-fulfilling prophecy?

FANTE: Always.

YOUNG: How often do the stories we tell ourselves become the realities we live?

FANTE: I think we create our own reality by the thoughts we have. Recovery for me has been learning how to choose my thoughts, learning how to listen to my thinking and not choose the negativity. I don’t have fights with people in supermarkets anymore. I honestly thought for years that my rage was who I was, that people who didn’t think the way I thought were lying to themselves.

YOUNG: I think it’s about letting go of all that rage and negativity.

FANTE: Right, but there has to be a facility for letting go.

YOUNG: And staying away, too, and I think writing became that for you.

FANTE: Oh yeah. Writing is so much more than therapy, because it gave me a sense of feeling good about myself. When I wrote my first book, I wrote it on my father’s typewriter using the paper he used to write with. Creativity is achieved in the doing, it’s not achieved in the thinking. Thinking about writing your great American novel or painting your masterpiece ain’t gonna cut it. Writing my first book Chump Change, which was essentially about my relationship with my father and substance abuse and his dog, I began to view it with compassion for myself.

YOUNG: How do you think your father’s successes and failures shaped your own?

FANTE: The first thing that comes to mind is my dad hated screenwriting. He really thought it was for buffoons. But there were a few good writers my father worked with whose work he admired, so he viewed the craft as a source of independence. It was a tool for him to pursue a lifestyle that he enjoyed very much. He was a golfer and a gambler and a drinker. The ’40s and ’50s in Los Angeles before it got overpopulated and smoggy, I mean god, what a great fucking town. All these very famous writers would come in, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Faulkner came to Los Angeles, and the studios just threw money at them. My dad was one of those guys. So he was playing cards and drinking with wonderful, imaginative people. And Los Angeles was a great party town, though it was all hidden, nothing like today. These people were wife-swapping and just all kinds of absurd, decadent behavior. It was great.

YOUNG: [laughs] Amazing. So how did that impact you?

FANTE: My father was the greatest influence on me in terms of literary sensibility. I knew he was frustrated, and I never wanted to be a screenwriter. [laughs] Everybody out here is so fucking clever, and they’re always putting deals together, and there’s always so much big talk and so much ego, and I just have to separate myself from that.

YOUNG: How do you ultimately free yourself of the past in order to own your future?

FANTE: By staying in the present. And that’s not a glib answer. The way to stay in the present is to have a love for what you’re doing and a vitality and a sense of well-being that is generated by your art. I’m a happy person now. I have a wife that loves me and who I love, after all those years of awful relationships, and we have a seven year-old son. When you find the thing you’re supposed to do as a person, then all the pieces seem to start coming together. Shit, man, that’s it.

FANTE: A FAMILY’S LEGACY OF WRITING, DRINKING AND SURVIVING IS OUT IN BOOKSTORES TODAY. FOR MORE ON DAN FANTE, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.