A Shore Thing

In 1965 Stephen Shore was a senior in high school at Columbia grammar on the upper West Side when he stopped going to school. To say that he fell in with the wrong crowd is putting it mildly; Shore fell in with the Warhol crowd and quickly became the unofficial archivist at the already world-famous Factory. Forty years later, he’s gone from a lone gun to a very fashionable fashion photographer. His latest exhibition at 303 Gallery has the Factory front and center; there Shore is himself an irresistible character, in dialogue with the Velvets, Andy Warhol, and Edie Sedgwick (whom he never really could get a handle on). In the back room Shore shows color photographs from his street series, in which he photographs unsuspecting passers by in the streets of New York. It’s two looks by and at a photographer whose documented the city for decades, and whose let it document him in turn.

ALEX GARTENFELD: So you didn’t like high school,

STEPHEN SHORE: I found school boring. I was learning the history of film and going to two or more films a day. I made a short film that was shown the Fimmakers Cinematheque that was run by Jonas Mekas, the same night that Andy was showing a film called “Real Life in the Castro.” I was introduced to him afterward and asked if I could come to the Factory to take pictures.

AG: Was the Factory at Union Square yet?

SS: No, 42nd street between Second and Third Avenues. I don’t even remember what I knew about the Factory—but I had heard stories about it.

AG: Had you heard bad things or exciting things?

SS: I would say exciting things. But I really don’t remember what I knew about it. It was something that seemed like it would be great to photograph. There was no way at the time to understand how unique this circumstance was.

AG: What was your first day when you got there?

SS: Well the first thing, was I went to the set of a movie called “Restaurant.” It was a restaurant on the Upper East Side called L’Aventura and after the filming everyone went back to the factory. As I recall later that day there was a party. I was hooked.

SS: I met a lot of people that first day, Gerard Malanga, and Sandy Kirkland—

AG: Do you still keep in touch with them?

SS: No. I saw Gerard about five years ago at an opening of the show. Of the people I met on the first day, the only person I maintained a real friendship with was Sandy Kirkland. She died a while ago. Gordon Baldwin—I met a lot of people that first day. [POINTING] This is Andy doing a portrait of Marcel Duchamp. The person who I assume arranged it is this man Sam Greene who I had lunch with yesterday. So he’s the only person in this room who had ever seen this. I hadn’t seen him in forty years.

AG: He has a great, lively expression there. It’s not an expression you normally see on him.

SS: No, and I think that’s why I like the picture. It’s here I am—Marcel Duchamp. What am I supposed to make of this?

AG: Did you see yourself documenting what was going on? You’re bringing the posing out of your subjects, your friends. It’s more than just a documentary quality.

SS: I started thinking I was documenting what was going on. But very quickly within days I started making friends with people there. Then I was just someone who was hanging out at the factory, so the pictures took on a different—I wasn’t anonymous. There are other pictures of Andy where he’s making faces for me. Or in this one, he’s reacting. He knows he’s being photographed. I’m not an invisible camera that is pretending I don’t have a presence in the room. People knew I was there but they were comfortable. I was a kid one and I was a regular there.

AG: Did you consider this your primary practice?

SS: This was it. I was doing this every day.

AG: All of these people have an incredible hagiography—Edie Sedgwick is a very au courant one. Is there anyone whose biography you feel like you’re writing, or amending?

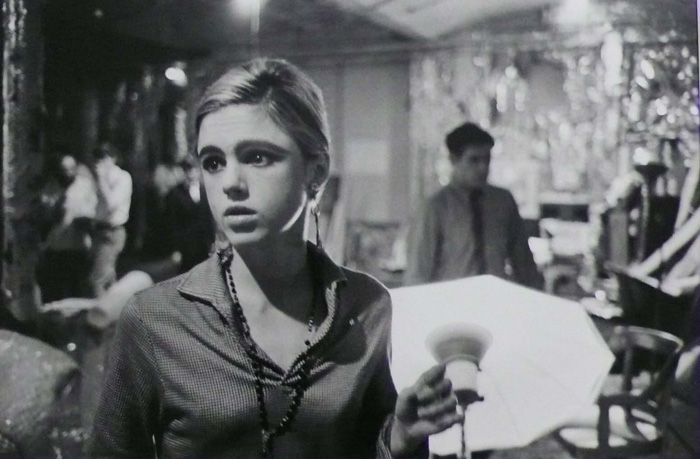

SS: I don’t know how much a photograph can add to a biography, the way a film or writing or narrative medium could. Because it’s a frozen image. For example, here is Edie with a very genuine smile, but you don’t know what the circumstance it.

AG: It’s a very wholesome look.

SS: But you don’t know what she’s doing. Is she acting or is it genuine—or is it an in between expression? Has someone just said something that disturbed her for a second? So they have a reality of their own, but I don’t know if they add to a biography.

AG: How long were you in the Factory?

SS: On and off for three years.

AG: And what was the end—or did you just move to something different?

SS: I moved on to conceptually based sequences. I did that right after I left the Factory in 69 or 70. It formed the center of my first show, which was at the Met.

AG: That’s a good first show.

SS: That’s a damn good first show. I could relax, because I had made it and then it was going to be all downhill. [LAUGHS] The pressure was off.

AG: How did the Met find your work?

SS: I submitted it. I was not expecting it. They weren’t showing contemporary artists. They weren’t showing any living artists. I didn’t know that they had changed their policy. I left my portfolio the way I did at other museums around the city. I came back a week later and one of the pictures was framed. They said, “Do you like it framed?” I said yes. And they asked if I wanted a show. That was a year that they had their first show of living artists. They had Jules Olitski and Joseph Cornell.

AG: That’s a strange trio.

SS: Yeah, it was strange work. As I recall it was Jules Olitski’s sculpture and not his paintings, and Cornell’s not boxes but paintings.

AG: Did it feel like a radical force in New York to have the Met doing contemporary shows? How early was this?

SS: This was ’71.

AG: OK, so Jules Olistki had been around for a while.

SS: Oh yeah, and Cornell had been around even longer.

AG: how old were you?

SS: I was 23.

AG: Were you the youngest living artist to show at the Met?

SS: Probably. I might have been too young. It was a real shock to me. It was something you might want to dream about, but then it happens and it’s like now what.

But I would say another event for me was the Moderna Museet in Stockholm did a big Warhol show in ’68. The catalogue was curated by a young curator named Casper Koenig, who now is the director of the Ludwig. We did the editing of about 160 pages of photographs in the catalogue. After we did the editing we were in a loft Soho and he said,

I have something to show you,” and he pulled out Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip. Then he laid it out on the floor of the loft. It was a mind boggling experience and I immediately went uptown bought every Ruscha book he ever made.

AG: You never have to work again then? [laughs]

SS: I still have them.

AG: Why did you decide to present the photographs from the Factory now?

SS: I had been with 303 for nine years and we thought it would be interesting to do a show of black-and-white work, and have some new work in the back. They’re New York pictures, with two different New York scenes, done in 2000 and 2001.

AG: In a way the two series are opposites: both documentary photographs, but you occupy such different roles. In the Factory photographs, you’re a character in obvious dialogue with your subjects. In the new street photographs, you’ve done a lot of work to reduce that dialogue.

SS: In a funny way, yes. These were done with an 8×10 Field Camera. The camera is this big [GESTURES WITH ARMS SPREAD] on a tripod and I just stand there with the cable running down and this huge camera. People walk around me and no one cares. I’ve never felt so invisible on the street. I mean, these people saw me because no one bumped into me, but it’s like I was a hot dog vendor or something.

AG: Maybe they thought you were selling service taking portraits, and by ignoring you they were rejecting your request.

SS: I think they may have thought I was doing something architectural. These are two from a larger series. In some I was photographing someone in the crosswalk. I’m standing next to them with the camera and they are oblivious.

AG: It’s an uncomfortable feeling.

SS: They just thought I was going about my business and had nothing to do with them. I don’t think they understood the camera was aimed at them. I could get moments where people were totally unguarded. I’m not responding. I’m not responding to what I’m seeing, I’m creating a stage set and then I’m waiting for something to happen, trusting that New York is interesting enough and people are interesting enough that something is going to happen on the stage set in my head kind of floating out there in space. I know that’s where my focus is going to be. I’m watching the people come and go and wait for an intense moment.

AG: Is that how they’re connecting the two series? By contrast, in terms of the role of the photographers with the subjects?

SS: I hadn’t that thought about that, but they are photos of that.

AG: So when it came to it, how did you—

SS: Why did I do this? I’m not interested in doing the same kind of picture over and over again. I pose problems for myself. Sometimes they are aesthetic problems and sometimes they are logistical problems. I’ve always loved New York street photography: Gary Winnogrand was always one of my favorite photographers. But he used a 35mm Leica; he saw something and responded with extraordinary speed. I wanted to approach it in a different way. The camera I use is a Deardorff, which was made years and years ago, with a wood slot that pops into the back of a camera and covers half the negative so you make a 4x10inch negative. Then you take a picture and move the slide and take another picture on the sheet of 8×10 film. So that’s what I did for these. The challenge was when I’m setting up the picture, none of these people were even nearby. I might have seen something completely different, since I’m under a dark cloth and once I focus and get the picture set up, then I put the film in. Then I wait.

AG: In reference to those you talk about the picture being mute, but you seem to have an intense dialogue or even a narrative with them. Even if they are still.

SS: I think it kind of implies—I don’t think its narrative the way film is narrative. But it implies something.

AG: Did you arrange these two here and the room in front—I hate to even ask this. But with any kind of social commentary, in terms of these being tourists shopping at Bath and Body works, versus those who might seem a bit savvier.

SS: My main objective was not drawing a contrast between the works, but just connections that it’s New York and it’s black and white. Maybe it’s as simple as that. It may get back to what you’re saying in that I’m anonymous here and in the others I’m interacting with them.

AG: You’re doing more commercial based work now.

SS: I’ve been doing more fashion photography.

AG: Do you like it?

SS: I love it.

AG: Did you think about it in terms of taking of your earlier photos?

SS: No it’s very different because it’s collaborative. You have a stylist and if you have a

good model, the model is contributing. The make-up and hair stylist contribute too. The stylist has a lot of power. There are stylists that I like working with. Often what comes out is more than what either of us thought about going in.

AG: How do you approach a fashion shoot? Do you approach them with a very strict concept?

SS: I have concept and the stylist will have a concept but we’re flexible so I don’t go in and say this is how we’re going to do it. So we can also respond to the specifics of the moment.

AG: Were you surprised—did you see yourself doing fashion photography?

SS: I never imagined it.

AG: What turned you?

SS: A very imaginative man named Thomas Meijer who is the creative director of Bottega Veneta. He likes art photography; he’s a person of exquisite taste. He approached me and knowing I had never done anything like it, asked if I would like to do a campaign.

AG: How did you approach that first campaign?

SS: I was worried about all of it. But that is what was interesting. If I only try to solve the problems I set for myself, then I’m limited by what I can conceive of. I can’t solve a problem I can’t conceive. But if someone else gives me a visual problem, it can be out of the whole realm of my normal practice.

AG: has it changed your art practice? Whether you’re more open to collaboration?

SS: It hasn’t but it’s something that I loved. For the last year, I’ve done eight spreads for Elle.

AG: That’s great to see you taking a risk and they’re taking a risk.

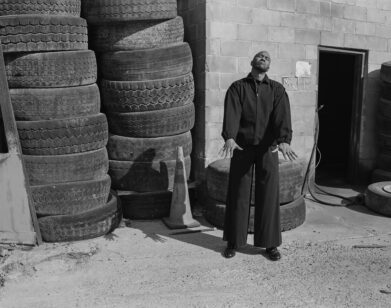

SS: Well they’re not taking a risk anymore. [LAUGHS] Editorials, they come and go. Three weeks ago, I did two things for Dubai for Elle. Roberto Cavalli was opening a nightclub and I took a portrait of him and a couple architectural shots. The next day I did a fashion shoot in what looks like the old part of Dubai, but I couldn’t tell if it was built a couple years ago in the old Arab style. But it looks older. It was 102 degrees He had Cavalli champagne and vodka. He had a deal with Audi because he had a Cavalli Audi with a crest on the side.

AG: Do you have a few you want to highlight? Like these are prime examples of Stephen Shore in the factory?

SS: I have a lot of work on the factory. This is a good cross section of different things.

AG: What is this from?

SS: This is the Velvet Underground in the factory performing for a film. This was ’66. This is when the neighbors started complaining about the noise and the police came to the factory.

AG: Was it the first time the police came to the factory?

SS: It was the only time the police came into the factory. This is Sterling Morrison, after the Velvets broke up. He went back to college and got a PhD in Medieval Literature and I lost track of him we were friendly at the time. And fast forward to 1982 and I get a job as head of the photography program at Bard. I get a call from Sterling. He’s living in Poughkeepsie about 40 minutes from Bard. He needed a job. I called a few people and said “The guitarist from the Velvet Underground has a PhD in Medieval literature and wants to teach here. What can we do?” This was very exciting. I just got this blank stare when I said Velvet Underground. The students knew, but the administration had no idea. The band had broken up about fifteen years before they were born and they all knew them. Can you imagine the students having a member of the Velvet Underground teaching them?

SS: I have a lot of work of Edie.

AG: Were you close?

SS: I don’t even think she spoke to me. I was a kid and she was aloof. But she was incredible to photograph.

AG: I love the photograph of Andy Warhol in front of the white backdrop.

SS: for a while I had a roll of seamless white paper up at the factory. So I was doing portraits of people that came in. It was up for maybe a month or two, this was my little portrait studio. This is how Andy was typically dressed at the time.

AG: It’s such a natural look though; it’s not how you’re used to seeing him. What was his role or his encouragement in photographing the factory? Did you

SS: Not as something archival. We looked at the pictures. He was encouraging.

AG: Was he interested in the pictures?

SS: I don’t remember. But the Warhol Museum has a bunch and the only way they would have those, is if I gave them to him. But I don’t remember doing that.

AG: They hang on to things.

SS: Yes. But obviously I was giving him pictures all the time. I don’t know if we had a completely trusting relationship. But he was completely. Unguarded with me, he was more like an uncle with me in that he would give me advice. If I said something completely inappropriate in a public circumstance he would say to me “Now Stephen you shouldn’t say these things.” He lived on 89th street and I lived on 59th street and we would share a taxi uptown. We had really great unguarded conversations.

AG: Was it a contrast from his general demeanor?

SS: Well he had a general demeanor and a public demeanor. The way he would act in a public setting was the face he would put on. I didn’t see that at the factory particularly. I have a story. In those days, CBS Channel 2 would have old Hollywood movies all night long. One day I got to the factory, this is after I shared a taxi uptown. I got home and there was a really terrible 30’s tear jerker with an actress called Priscilla Lane. The next day I got back to the factory and Andy asked if I had seen it and I said yes. He said “What happened?” and I recounted the plot. He said “Because I started crying and fell asleep, and the funny thing is that when I woke up the television was off so my mother must have come in and turned it off.” I remember thinking here is Andy Warhol telling me that he cried himself to sleep this horrible movie and his mother came in and saw little Andy with the television on and turned the television off.

AG: So you had a sense of the significance of Andy?

SS: Oh yeah, I got into the factory in ‘65 which is three years after the Brillo boxes and the Marilyn. And he had already moved past his first phase of filmmaking with the static film and was into the improvisational film. If you were living in New York and reading the paper and interested in the art world he was famous.

SS: My mother loved Andy.

AG: Is your mom relate to your life—was she excited or was she protective of you?

SS: Well, I dropped out of school and they were upset. But after a while they gave up. And Andy was famous, so if Andy came over to my apartment and my father would chat him up and he thought that was cool.

303 Gallery is located at 525 West 22nd Street, New York. Show ends July 18th, 2009.