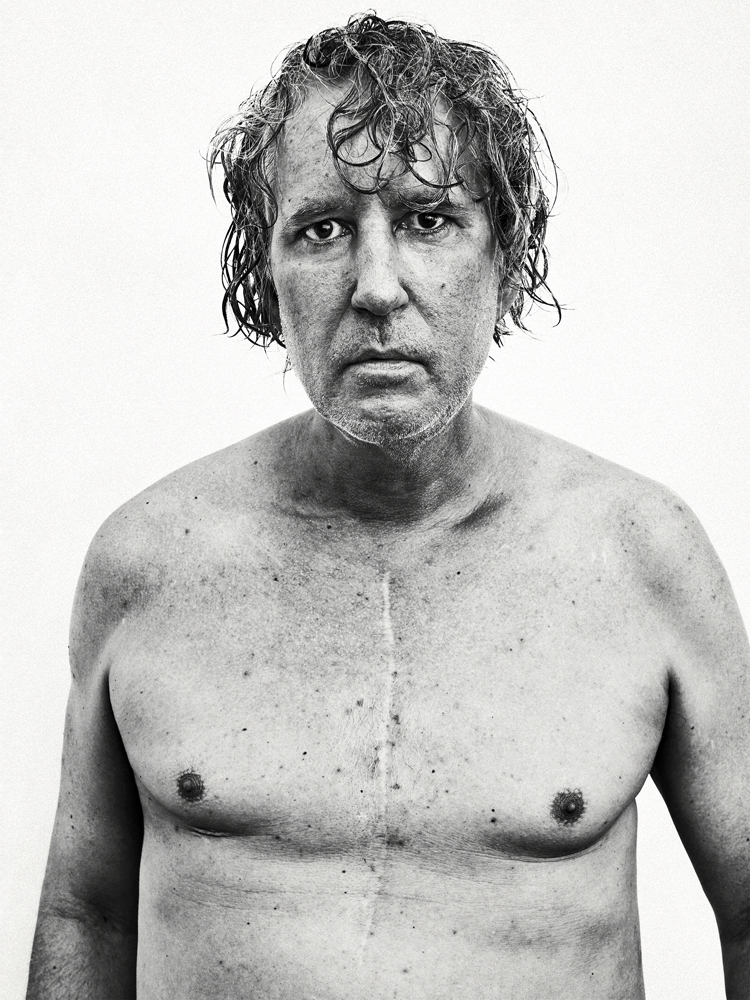

Raymond Pettibon

FOR THE WHOLE PUNK-ROCK SCENEâ??I SHOULD BE BITING MY TONGUE HEREâ??I HAD TO HAVE A SENSE OF HUMOR. Raymond Pettitbon

I first became aware of Raymond Pettibon in the early ’80s, when I was visiting my parents in Los Angeles. Thurston and I came across his zines in a store somewhere, and we became keenly interested in them. One Sunday afternoon, we went to a house party in Hermosa Beach, a languid, slightly funky enclave that never became a resort town but rather a suburban neighborhood by the beach. Black Flag were playing at the party, and Henry Rollins was singing in the kitchen. He came right up to me and sang in my face. That was maybe one of the best gigs I’d ever seen because it was so surreal and intimate and confusingâ??refrigerator, counter, Henry Rollins twerking before twerking existed in his little black shorts, fusing hardcore punk with suburban banality.

This was all new to us. Coming from the New York music scene, people didn’t have houses or garages, so no house parties viewed through the almost-too-bright L.A. sunshine. We went out to the backyard and there was Raymond. Someone introduced us. He was already sort of mythical in our minds. He was shy and dressed normallyâ??casually disheveled. No one from that area dressed in a stylized punk way. That was one of the things that made it so coolâ??South Beach as opposed to Hollywood. We got to visit with Raymond a few times. There was always a pile of his drawings spilling over on a tabletop.

Raymond’s drawings were way beyond illustrative. At that time, he had no relationship to the art world. I decided to write an article for Artforum on his work, as well as Tony Oursler’s and Mike Kelley’s, whose work also used high and low culture, eschewing the conceptual mantle of ’70s formalism. It was a way to get Raymond into Artforumâ??this was the mid-’80s. We also participated in one of Raymond’s films, The Whole World Is Watching: Weatherman ’69 as Told by Raymond Pettibon (1989). It was very informal, and the brilliant script carried the whole thing. It almost didn’t matter what the actors did. Whoever showed up to Raymond’s house became crew and cameraperson. The task happened to fall on Dave Markey, the musician and filmmaker (The Slog Movie, 1982; 1991: The Year Punk Broke, 1992), but it could have been anyone. Reading off cue cards made it immediately a natural deconstruction, a Nouvelle Vague film à la Hermosa Beach. Shortly after that, Raymond began showing at Ace Gallery in L.A. He was like a flower opening up with a little attention.

This interview took place over lunch in SoHo in New York, just before the opening of Pettibon’s latest show of drawings at David Zwirner gallery. This winter also brings the release of two Pettibon art books, a definitive collection of his work from Rizzoli and Raymond Pettibon: Here’s Your Irony Back: Political Works, 1975-2013 (Hatje Cantz).

KIM GORDON: I’m sorry I’m not going to be here when your show opens. I’ll be in L.A. Are you going over to Zwirner for the installation?

RAYMOND PETTIBON: Yeah. Over the last couple of days it’s like Heckle and Jeckleâ??except, times five. [Pettibon orders a vodka and tomato juice, and Gordon orders iced green tea and sake.]

GORDON: Sake is supposed to be the purist thing. It supposedly helps Alzheimer’s and heart disease.

PETTIBON: We got some sake from the place next door to the gallery the other day.

GORDON: How’s Bo [Pettibon’s son]?

PETTIBON: Great. He was up and about this morning.

GORDON: What time does he get up?

PETTIBON: Usually around 6 a.m.

GORDON: Wow. Coco [Gordon’s daughter] was always a late sleeperâ??hard to get to bed, hard to get up. Kind of how that rock-star stuff goes. How

old is Bo now?

PETTIBON: He’s almost 2. He’s a good kid with a nice disposition.

GORDON: So, I should ask you all the questions that I hate being asked. [laughs] Like, what’s it like to be a man making art? That would be the opposite of, What’s it like to be a girl in a band?

PETTIBON: Yeah. I don’t know the answer.

GORDON: Okay. What was it like growing up in a beach culture? Because you grew up really close to the beach, right? Did you go to the beach a lot as a kid?

PETTIBON: Yeah, constantly. During the summer I spent all my time at the beach.

GORDON: Was there a point as a teenager when you just stopped going to the beach? I was talking to somebody about the L.A. hardcore scene, and they were saying that it was hard for them to picture punk rock at the beach. Like, the aesthetic didn’t mix or somethingâ??black forms in the sand.

PETTIBON: Well, I did go surfing.

GORDON: I used to surf when I was 10 or 11, at Latigo Point.

PETTIBON: Malibu.

GORDON: Yeah. My parents had friends there. So, when did you stop surfing? Was there a point when you just kind of got more into staying in your room and drawing?

PETTIBON: In the South Bay, where I lived, it became a condition that you could go the whole summer without breaking. I grew up near the beach, but it wasn’t like I could step out of my bedroom and be in the water.

GORDON: This summer I went out to stay with some friends who live at Point Dume. It’s one of the most rarefied of surfing places.

PETTIBON: Oh yeah, of courseâ??like the northern edge of Malibu.

GORDON: It was interesting meeting really original residents from there, people who grew up there. I guess I’m really nostalgic for that

area because I’ve spent so much time there. People don’t think of California as having a history.

PETTIBON: You mean a history based on, like, how far you are from the beach?

IT JUST BRINGS ME DOWN to EARTH…TO REALIZE HOW OUT-THERE AND FAR AWAY AND PALTRY the AUDIENCE IS THAT GETS WHAT Iâ??M SAYING. Raymond Pettibon

GORDON: No. I mean, L.A. prides itself on newness or being the last frontier or just not liking old things and tearing them down to build new things. But Malibu history is interesting to me. My mom’s family was one of the early families in California, so there’s history going back to the 1840s or ’50s.

PETTIBON: Like the settling? Pre-Gold Rush?

GORDON: Yeah. They came over in the Gold Rush, actually. I have all this guilt about raising my daughter in the East. [laughs] I don’t know. Coco’s very anti-California. It’s her way of rebelling.

PETTIBON: That happens, you know. You rebel against where your parents are from.

GORDON: A few years ago, we went out to Big Sur, and then up to see friends at Point Dume. It was 80-degree weather on the beach, and Coco is wearing her black leather jacket. It was a great photo. [laughs] But it’s like how Mike Watt [the musician and former Minutemen bassist] feels about [San] Pedro. Although the history of Pedro is so interesting.

PETTIBON: But Pedro is a different town, because it’s a place that no one would go to. It’s off the map.

GORDON: Totally off the map. But I remember this place where he rehearsed, which was a former magazine at Fort MacArthur, built before World War I.

PETTIBON: The Fort’s still there. Artists are still using parts of it as studios. And that’s where Watt practices and records. It’s a beautiful place.

GORDON: I think someone should make a film about early California.

PETTIBON: That would be a great place to do a film.

GORDON: I want to be in your next movie.

PETTIBON: I was blessed with a lot of good actors. I have one film I want to do with Watt, but he’s always on the road. I’ve put so many screenplays on the shelf.

GORDON: But your scripts are the best.

PETTIBON: I remember The Whole World Is Watching took, like, four days. And that was reasonable. It wasn’t rushed. I have finished scripts that have been lying around for, like, 30 years or more.

GORDON: Really? Do any come to mind in particular that you were fond of?

PETTIBON: There’s several. I was talking to one guy recently who brought up the script I have about Batman. It’s about time that we make it.

GORDON: It’s really time for you to get back to it.

PETTIBON: I agree. And zines are another thing I should have been doing all along. But in The Whole World Is Watching, you just made the screen glow. [Gordon laughs] No, truly.

GORDON: It was super-fun because the script was so amazingâ??that, and Sir Drone: A New Film About the New Beatles [Pettibon’s 1989 film about two teens trying to start a punk band; it stars Mike Watt and the artist Mike Kelley, who died in 2012] are definitely my favorites. Sir Drone is epic.

PETTIBON: That was done in two days.

GORDON: It said so much about everything that was going on there. It still holds up. You should screen it at your show. You know I have this little survey show of my art up right now at White Columns, and in it we’re showing The X-Girl Movie [the 1995 promotional film for Gordon and Daisy Von Furth’s clothing line], which looks amazing. It’s one of Phil Morrison’s best works. It holds up. It’s kind of great for people to see something about a time, a history, without belaboring anything, you know?

PETTIBON: Yeah. I saw Sir Drone not that long ago. Like, two months ago in Brooklyn. And this was for the first time since I’d made it.

GORDON: How did you feel when you saw it?

PETTIBON: It just broke my heart.

GORDON: Oh, I bet. I know it’s hard to watch.

PETTIBON: Like this Rizzoli book that’s coming out. It was the last time I saw Mike.

GORDON: Oh, wow.

PETTIBON: The interview we did was less than a year ago.

GORDON: And there’s another book that’s coming out as well.

PETTIBON: Yeah, that is the political one. They’re coming out the same time.

GORDON: Does it have any of your Twitter stuff?

PETTIBON: No. Have you seen my Twitter stuff?

GORDON: Oh, yeah. I feel like I need CliffsNotes, but I totally follow you. It’s almost like be-bop. Most of the time I don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about.

PETTIBON: It’s not huge. I’ve got just under 8,000 followers or whatever. But what social media has doneâ??Facebook, Twitterâ??is show the audience. I don’t have an audience. When I make my work, it just goes out into the ether. I have a thick skin and it just brings me down to earth, you know, to realize how out-there and far away and paltry the audience is that gets what I’m saying. It’s depressing if I let it get to me. And it’s the same with hanging a show, the way it’s put up, like, three stories high and you can’t read a single word.

GORDON: I read on a website that you want to make a nice drawing from a personal point of view.

PETTIBON: Just to make drawings, like lyrical drawings and stuff. I resent having to be put in the place that I even have to engage in making political works. But the thing is, no one the fuck else is, right now, in the art world. And, for god’s sake, no one in journalism is. So it’s like I’m reporting in the drawings, just bringing up the news.

GORDON: I feel like that sometimes. Recently some work I made could be seen as feminist art or work that relates to the body.

PETTIBON: Yeah, but don’t apologize for that.

GORDON: Well, that’s not my intention. You know what I mean? That’s just what I’m feelingâ??like it needs to be done.

PETTIBON: Sometimes there’s a vacuum that has to be covered.

GORDON: That never goes away. Like political art never goes away. Like your work No Title (You killedâ??murderedâ??) [2007] [The drawing shows a woman standing at a flag-draped coffin and pointing at President George W. Bush, saying, “You killedâ??murderedâ??my son!” On the other side of the coffin, Karl Rove says, “She’s crazy! It was friendly fire!” Dick Cheney says, “Don’t listen to her. She has no more authority over you than the world court.” Condoleezza Rice says, “She can accuse, but she can’t indict.” Bush replies, “You’re just sore because you lost your son.”]

PETTIBON: Some of that is said with a heavy heart. Like David Wojnarowicz, and what was all around him, the devastation of AIDSâ??you can’t ignore it. For my work, the distinction that sets it apart is that it doesn’t lend itself to easy identity politics. I mean, for Christ’s sake, whether it’s business, politics, journalism, as long as you bite your tongue and you don’t let escape the N-word or something, everything is fine and dandy. Meanwhile, there’s how many millions of people in the prison system? It’s a hell of a lot easier to bite your tongue.

I RESENT HAVING TO BE PUT IN the PLACE THAT I even HAVE TO ENGAGE IN MAKING POLITICAL WORKS. BUT THE THING IS, NO ONE ELSE IS, RIGHT NOW, IN the ART WORLD. Raymond Pettibon

GORDON: Did you ever watch the show The West Wing? I started watching it recently and I’m actually learning about how the government works in a way. It’s kind of embarrassing. Like, in one episode, the president, who I think is based on Clinton, ends up saying, “Yes, okay, let’s assassinate this guy from the fictional country of Qumar because he’s a political person who is coming here and is planning a terrorist act.” So they have him taken out. I was thinking about it in light of the debate over bombing Syria. We wanted to do it to teach them a lesson. It wouldn’t solve anything, but it would make them feel bad, which is such a high school tacticâ??like, giving them a slap on the hand in the form of a bombing. It’s crazy.

PETTIBON: [Journalist] Glenn Greenwald should be listened to because he’s not just critiquing the situation, he’s critiquing journalism as a whole.

GORDON: It’s also the whole thing of America having to be the world police. We have to control and manage the world so things don’t get too fucked up.

PETTIBON: Yeah, the “intervention” that is based on what’s good for them. Nothing good comes from that ever. You know that if you read your history.

GORDON: I was thinking that the way you approach Twitter reminds me of an era in French literatureâ??Emile Zola and Balzacâ??and the beginning of modernity and gossip. There was the best show early this year at the Met, where they had selections of impressionism on fashion [“Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity”]. They had these fashion magazines of the time on display with all of the Emile Zola references. And someone told me that Le Bon Marchéâ??the first department store in Parisâ??was where people used to carry on affairs in the dressing rooms.

PETTIBON: Wow … Fashion is underrated.

GORDON: It was those handful of artists who were reacting to fashion in their painterly work, and other people were saying, “Why are they so interested in fashion? They shouldn’t be doing that.” That’s really interesting to me, this disdain they felt for these painters being preoccupied with fashion. But fashion, at that time, was actually a way for women to go out in the world. There was one painting of a woman sitting at a café, drinking a beer by herself and kind of pretending to read but really watching people, that sort of thing. It fascinated me.

PETTIBON: Last night, Aïda and I were watching the film The Devil Wears Prada [2006], where Meryl Streep plays a fashion editor, and she gives this dressing down to the assistant. [laughs] You know, Aïda is working with Abel Ferrara on a film project about Pier Paolo Pasolini. She wanted to do this film based on Pasolini’s death. Ferrara is also doing a film on Dominique Strauss-Kahn.

GORDON: Did you see Olivier Assayas’s film Carlos [2010], about Carlos the Jackal? There’s a five-and-a-half-hour version that’s amazing. You really live this character. You would like it.

PETTIBON: He’s a pretty hardcore dude.

GORDON: It reminded me of your movies in a certain way. I really like Assayas’s filmmaking. He always has this globalâ??economy thing going on. Demonlover [2002]â??we did the soundtrack for that film. It was a parallel sound that ran along like another character.

PETTIBON: Weren’t you actually in one of his movies?

GORDON: I was in Boarding Gate [2007], which was one of his more minimal movies.

PETTIBON: If we ever have free time, it would be a dream come true to do another movie with you. It’s real easy to do. You know I don’t make demands on anyone.

GORDON: Yeah. Well, after I come backâ??if I ever come backâ??from L.A.

PETTIBON: That’d be great. I told you many years ago that I wanted to make one with Watt with robes in the Sunken City [in San Pedro], where there’s the ruin of a neighborhood that a landslide caused to collapse. One of those “Everyman” plays. You know, for the whole fucking punk-rock sceneâ??I should be biting my tongue hereâ??I had to have a sense of humor. Did you ever feel that way? Like you had to dumb yourself down a bit?

GORDON: I felt like maybe there weren’t a lot of people I could have a conversation with about stuff going on in my head. It’s not that I devalued them …

PETTIBON: No. Me neither.

GORDON: It was just … I always felt like an outsider to the music world in a certain way.

PETTIBON: Yeah. There was a major transgression to making that kind of work.

GORDON: There was so much less of an art culture at that time in L.A.â??and particularly in the South Bay. When I first met you, I just didn’t feel like you had any peers at all. And then maybe when you met Mike Kelley, that was one person.

PETTIBON: It’s not like me and Mike talked about literature.

GORDON: No. More politics, maybe.

PETTIBON: Yeah. Not even that so much. But I just really miss him …

GORDON: I wanted to ask you about sports. Do you see baseball as more of a suburban game and basketball as more urban?

PETTIBON: That’s a good question.

GORDON: I guess that’s another way of saying white and black. [laughs]

PETTIBON: It is, though. Like Darryl Strawberry: He went to Crenshaw High and he was a better baseball player than he was a basketball player, but he did both well. He distinguished himself with his swing as a baseball player. He is, like, 6’6″. And at that time, Crenshaw High had a great basketball program. Kids would gravitate towards basketball more than baseball in the inner city. Not that Crenshaw High is really that much in the city.

GORDON: No, but it’s on the border. And it’s pretty much majorityâ??or at least when I grew up thereâ??African-American.

PETTIBON: Yeah, for sure.

GORDON: Baseball is just a more popular game in America, right?

PETTIBON: No.

GORDON: No?

PETTIBON: I would think the opposite.

GORDON: I guess basketball has surpassed it. I always think of baseball as so existential. Like, you’re just out there in a field, in a big expanse of green grass …

PETTIBON: In my time, we had little league and junior league or whateverâ??before that, there’s the sandlot. Kids played baseball wherever

you can make a space. We played tackle-football on the street. You know, now we play basketball in the studio. We have a hoop. But we also have a pitching machine.

GORDON: I really want to start playing basketball. I actually bought a new basketball.

PETTIBON: Oh, man, you should visit the studio.

GORDON: Basketball and ping-pong are my two forms of exercise.

PETTIBON: Yesterday I went to the driving range. Do you play golf?

GORDON: There was just a moment when I was kind of into it. But I only really played nine holes.

PETTIBON: Where? In L.A.?

GORDON: My parents lived by Rancho Park. And my mom, later in life, got into playing golf. She and her male cronies would get up at five in the morning and sneak onto the back nine. I kind of just started getting into it. For a long time I was really puzzled by why people liked it.

PETTIBON: I’ve played 18 holes less than a handful of times. I’ve been in New York three or four years nowâ??the winters, the summers …

GORDON: Do you miss L.A.?

PETTIBON: In a sense.

KIM GORDON IS A VISUAL ARTIST AND FOUNDING MEMBER OF THE BAND SONIC YOUTH. SHE CURRENTLY FRONTS THE DUO BODY/HEAD.

Â