The Life and Death of Peter Beard

“This is it. This is existentialism,” Peter Beard says. We’re sitting outside on his Montauk property—the easternmost residence on Long Island, looking out on infinity—talking about art and life and death. Spring is rushing into full bloom, and with it come dozens of birds and the families of local deer celebrating the warming sun with song and wobbly-limbed dance. Over the course of his career, whether he is photographing the wildest creatures of East Africa or the finer-boned figures of the East End, in his writing, his diaries, or the monumental collages that bring them all together, Beard has made a living, and his legend, wrapping his work around such elemental, earthen subjects (the mass die-off of the elephants; the erotic life force of a nude; the native beauty of the natural world), often blurring the distinctions between them in the process. His totemic book The End of the Game, which was reissued by Taschen on its fiftieth anniversary last year, is a grand meditation on the balance between life and death set in Kenya, where Beard has spent as much of his time as possible over the last 60 years. The book is the most provocative and impressive statement on man’s relationship to the natural world I’ve ever read, and—spoiler—it does not have a happy ending.

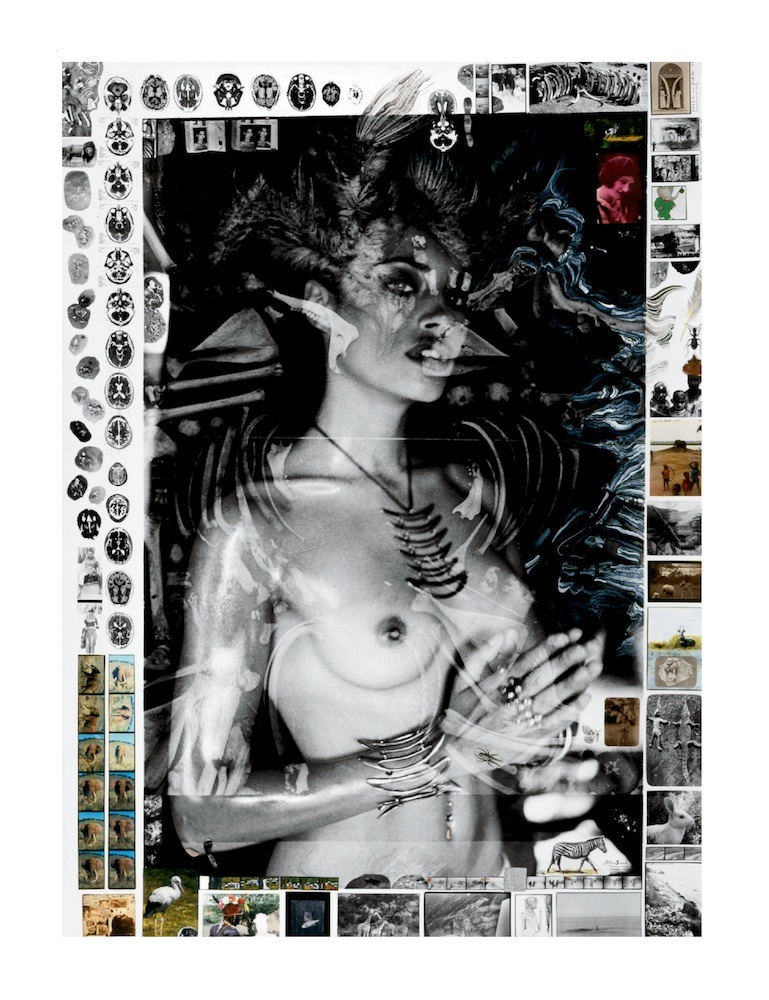

But at 78, Beard, by contrast, is among the most vividly alive people I’ve ever met, buzzing with the ebullience and energy of a child, and converting all of his wide-eyed wonder into his work and his adventures. Really, his collection of memories and their attendant scars may be said to be his greatest art, and the resulting work, himself, his masterpiece. He has certainly stared death right in the whiskers enough times in the process. In his picaresque memoir, Zara’s Tales: Perilous Escapades in Equatorial Africa, a collection of just-so stories that he entertained his daughter Zara with often enough that they developed the smooth, well-handled polish of myth, Beard writes of a few of these such occasions: being trampled by an elephant in 1996; getting run up on by a lion in the middle of the night; and surviving a shipwreck while researching crocodiles in Lake Rudolf in 1966, during which time he was briefly separated from one of the diaries he’d been keeping since he was a young boy. “For years I’d been keeping journals,” he wrote, “saving mixed-up scraps and clippings, dawdles and dipsy doodles, in daily diary layouts for the sheer pleasure of it, escapism.” But, now, full of the data he’d been recording on the crocs, this particular diary assumed a far greater importance. And, when it was recovered the next day, soaked in mud but carefully allowed to dry, page by page, by the group’s croc-skinner, the journal had taken on almost mystical qualities. “It was a gift from the gods: the ink-embedded photos never looked so good … Nine months of hoarded scraps had fossilized themselves together. Before my eyes the unrelated pieces merged in monstrous mildewed unities of trivial pursuit, bursting forth in clouds of spill and drip, great blossoms exploding in the wind. Soaked-through seepings turned from mess to magic.” From that day forward, we sense that Beard understood his diaries to be something else, something more, something like art themselves. They became studies for his grand collages and an ever-evolving Rorschach-y catalog of his experience—that is until July 1977, when over a dozen of the diaries, as well as the entire main house on his Montauk property, went up in flames, never to be recovered.

———

CHRIS WALLACE: What made you begin the diaries?

PETER BEARD: The first ones were … I used to do horseback riding in the South, and it was just things I’d be pasting. I think it was just an infantile desire to record things. I liked saving things instead of writing.

WALLACE: Which is how you get to photography, I imagine.

BEARD: I was given a camera by my grandma. No one else would give me one or allow me to get one. I got a wonderful Voigtlander. One of these bellows cameras.

WALLACE: Did you refer back to what you’d collected, or was it just about saving things?

BEARD: I’d love to show you through … I think I’ve got, like, fifty since the fire. But it is kind of fun to go through them. Not for any proud reason—it’s just infantile, that’s what it is.

WALLACE: But they’re a documentary of your existence. I keep a diary. I’m sort of obsessive about it—less so than I was when I was younger—but a lot of it is my trying to describe what I’m feeling or figure out who I am.

BEARD: Well, that’s a real diary.

WALLACE: But I won’t go back to it. I’m scared of who I was.

BEARD: I got around that. Being so pathetic, I don’t read. I just … do things—writing out interviews you can’t read, on pictures of footprints and things like that. I kind of like the idea of nailing the thing down and not really showing too much about it. There’s just so much you can take for collage nowadays.

WALLACE: Do you go back to the same piece more than once?

BEARD: I pretty much have to. Did you go through some of the diaries in the archives?

WALLACE: I didn’t. They’re sacred. They’re in a vault. But, for example, Danielle Luna on Burned Diaries, Montauk, when you paint over a print, pasting on details and writing or drawing in the margins, will you do that to several different prints in different ways, or do you do that just once and then that piece is done?

BEARD: I do some. I had some highlight moments in the early ’60s when I used to do a lot of rubbings. I used Afta; it’s an amazing chemical. If you pour it on something and rub, you get amazing results. Before that, I used lighter fluid and, well, I’ve always liked blood. Everybody thinks I am very sick, but the thing is, blood is better than any ink or paint. I did a pretty good one with blood yesterday, but unfortunately, the guy took it off. And you’ve seen the book with me and the bush baby on the cover [Peter Beard, Taschen, 2013] There’s some good blood in there. I’ll bring it out … I very much like this drawing. I did that when I was in school and I had nothing else to do, seething there with ideas.

WALLACE: This [I’ll Write Whenever I Can] was a remarkable picture to me when I was a kid. This was what it meant to be an adventurer and a writer.

BEARD: And here it is! You can’t do that with ink. I am not saying it’s great, but something you can do. I really do like looking through this … Oh, look. I love this squirrel …

WALLACE: There is an article in the New York Times Magazine today in defense of squirrels.

BEARD: We’re so full of shit on all of our sentimental views. Everybody has done an elephant book now. People are like, “Oh, the poor elephants.” Of course, they were shooting them. It’s like Auschwitz. These elephants went though hell. This one is good. [turns to an image of dozens of elephants photographed from a plane] This is what you call nature studies. This is a gangbang of social units. Misery loves company. You can see the devastation. [turns page] I like this one. You’ve seen that on the poster? Machine in the Garden, Tsavo is what it’s called. You can see the dried side of the tusk. There is a footprint! There are no words that you can really read. I studied with Josef Albers at school, so …

In 1914 Karen Blixen arrived in Africa, Beard wrote in The End of the Game, “full of dreams, ready to be reborn.” Almost 50 years later, a young Beard bought 45 acres at the edge of Blixen’s former farm and, if he was not exactly reborn, he has never really aged since then. An heir to fortunes from both the Great Northern Railway and Lorillard Tobacco, Beard was born and raised in Manhattan. He attended each and every one of the schools his father had (Buckley, Pomfret, Felsted, in Essex, England, and then Yale). But he seems to have run as far and as fast as he could from that legacy, choosing instead to align himself with the “gentleman explorer” types in Blixen’s proximity. In 1961, Beard’s cousin Jerome Hill provided an introduction to Blixen, who had by then left the Ngong Hills of Kenya for good to return to her native Denmark. The meeting seems to have been monumental for Beard, a blessing, and a welcoming in to the tribe to which he aspired.

WALLACE: You started to talk about it in Zara’s Tales, but why Kenya? It seems like it was almost a lark.

BEARD: Well, I used to collect African books, and when I first went to Africa, I went with Darwin’s great-grandson [Quentin George Keynes]. We started off in Cape Town and went off through Bechuanaland—now it’s Botswana—then Mozambique, and then Madagascar and Kenya. It was a great trip … This is early Iman in my bathroom at Hog Ranch … That first taste was in 1955. I had to go back to school. I just went to Yale, just got in, and I didn’t even stay for the graduation. I mailed in my thesis paper.

WALLACE: You didn’t bother to pick up your diploma?

BEARD: No way. I was going right back to Africa. I went on the boat—around the Cape of Good Hope to Madagascar and then Kenya … Well, this is a very good blood. You can see the hair and the ears. I dare say that Bob Colacello wrote in his book about Andy Warhol [Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up, 1990] that I would insist on putting blood on everything. Completely untrue.

WALLACE: All these birds … It’s really magical.

BEARD: It’s fantastic to watch. You get some really good woodpeckers on that.

WALLACE: Aside from horse riding in the South, you were pretty outdoorsy, catching frogs and fishing and just generally Huckleberry Finn-ing around.

BEARD: Well, I was. I had a trap line.

WALLACE: What did you catch in your trap line?

BEARD: Oh, everything. Even minks. Raccoons, foxes … My next door neighbor was into selling the things.

WALLACE: You were like a pioneer fur trapper.

BEARD: Exactly. Nothing I’d do now. Look at these. Very bloody from circumcision ceremonies… [Beard takes out photos of Kikuyu men and women undergoing ritual circumcision] It only takes about five minutes to do it. These are the women. That’s men. This is the truth of Africa. This is rhino horn. I did a book on the Masai … This girl is so beautiful.

WALLACE: Is that Lara Stone?

BEARD: No, it’s way before that. But I like Lara Stone. Did you see the Pirelli Calendar I did [in 2009]? You’ve got to get it. Lara Stone is the hero. Anyway, this girl is from Texas and she was so great. That’s all blood. I think that’s nice. That’s the world record elephant tusk. This girl is fantastic.

WALLACE: Where did you find your subjects?

BEARD: Well, she was a dancer. I did so many pictures with her. She was so great. This was at the edge of the cliff. These are the medicinal artifacts of the Masai.

WALLACE: Oh yeah, the tusk pipes. At the very end of Zara’s Tales, you describe these ivory pipes and their shamanic powers. And then your life is flashing before your eyes, because you’ve been cut though with one of them—well, with an actual tusk, where the elephant gored you.

BEARD: Here they are. “Of all the medicine men Lenana was the greatest.” That’s this man’s father. “All Masai acknowledge him as their lord and pay tribute to him.” That’s a quote from [Sir Alfred Claud] Hollis, who did the fabulous book on the Masai [The Masai: Their Language and Folklore, 1905]. I’ve got huge collections of these.

WALLACE: In your various near-death experiences, did you come out of it with a vision of the afterlife? The famous white light? Or some sort of theology? Did you talk to God?

BEARD: It took me a long time to get through. When I got hit by the elephant, my vision didn’t come back for a while … Now, here is [Francis] Bacon. I am the only person who can say, “Look, this is what his process looked like.” Oh, he was the best. The best!

WALLACE: How did you guys meet?

BEARD: I first saw his work at school in England, and I used to do faces based on Bacon. Obviously, I could never do them as well, but that’s how I started. Did you ever see the Kamante book?

WALLACE: Is that your book with Blixen’s majordomo, the sort of hero of Out of Africa [Longing for Darkness: Kamante’s Tales From Out of Africa 1975]?

BEARD: That’s right. I did a signing in Berkley Square in London. There were 500 copies; they disappeared very quickly. And Bacon came to the opening of the book! I got really into doing Bacons in 1956, ’57 at Felsted. I was just trying to copy Bacon, but it’s very difficult to copy.

WALLACE: No kidding.

BEARD: This is Bacon, and that’s me. This was really fantastic. I loved going up to his place. We used to have a lot of meals. He was very generous. I looked up to him. He gave me a great quote when we were talking about existentialism. I did a lot of interviews with him. He said something like, “Existentialism is when you throw a leaf onto a brook, and the brook doesn’t change.” That’s not quite it. I have this Bacon quote in here [Dead Elephant Interview, March 1972, 7 Reece Mews, London S.W.7]: “You can’t dictate to other people what they see about a painting; everybody sees things differently… It affects us all in different ways. I’ll tell you how I think of my own work: It unlocks the values of sensation. Most abstract art does nothing for me. I just always see it as a very beautiful or not very beautiful pattern. I feel that nearly all abstract art is really decorator’s art, and that means to decorate a room, or make a ‘pretty’ room or a lobby for someone.” Just devastating to Rothko and the rest. “There comes a moment when some image seems to be right—sensationally right (in the correct meaning of ‘sensation’ aesthetically right. Aesthetic is artificial—something that belongs to art, whether it’s music or painting or whatever. It’s a structure within the medium which is the aesthetic.” One Bacon just went for $140 million or something out of this world. Bacon is just so much more … There is a beginning and an end. But how do you like this blood? I had some very nice portraits of his but they’re ripped out … [a deer walks up to us; I take out my camera phone]

WALLACE: Do you think it’s crazy that everyone walks around with a camera in their pocket these days?

BEARD: They get much better pictures than me. Don’t move too much!

WALLACE: It’s remarkable that she’s come this close.

BEARD: She senses that you came all the way from New York.

WALLACE: I’ve got to get a good picture.

BEARD: Did you get it?

WALLACE: Yeah.

At various points in our chat, I try to explain Instagram and internet art to Beard, who seems to have anticipated a great deal of it: the sourcing of images, owned and otherwise, for collage; the remixing; the meme-ing of iconic images; the overt politicization; the wit; the irony; the dramatics; the vanities and insecurities (whenever we are not flipping through his various books, he keeps any image of himself, images he has made frequent use of in his collages, turned away). For a while, too, I wonder, despairingly, what Beard’s work would be like if he’d come up in the Tumblr generation, the Instagram generation, which both draws heavily on his work and utterly disregards it, as is its wont. A solo show of his at the Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton opening June 18 will certainly raise some of these questions. But I wonder, too, where else his work and life (or at least the spark of the adventurer artist that he kept alive and glowing) can be seen. While we are watching the Madagascar episode of Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown, listening to Beard’s side commentary on the island’s lemurs, and its crazy ecosystem, I just know that we’d be far poorer without it.

WALLACE: Did you feel like you were a link in a chain? Like you were a part of some sort of legacy?

BEARD: Yeah, it shows. [he flips to a picture in Peter Beard, 2013] This is where [Karen] Blixen used to sit and drink her coffee. This area was always closed. This is her husband [Bror von Blixen-Finecke] there. This was 1904. She came later on the boat. This is with Frederick Selous, Teddy Roosevelt’s hunting buddy.

WALLACE: Did you feel like you had a connection to those guys?

BEARD: Well, you do. I collected their books. This is George Eastman [the founder of Kodak]. I used to camp right here. That’s personal. That’s Osa and Martin Johnson. It’s just amazingly invaluable. This is Veruschka von Lehndorff. I started out with blood, but this is kind of nice without.

WALLACE: It’s very Bacon-esque. The heart.

BEARD: Well, you know, everything Bacon does only he could do.

WALLACE: Of course. He owns organs and those horror elements.

BEARD: Yeah, but it’s amazing.

WALLACE: You worked with so many of the great 20th century artists.

BEARD: Well, not really. Just Bacon and Warhol.

WALLACE: Dalí. The Stones. Avedon. Andrew Wyeth. Terry Southern.

BEARD: Here is Bacon painting me painting Bacon.

WALLACE: Does that give the piece a little extra bit of charge, when a major artist is your subject? Do the resulting pieces have some of their energy in them?

BEARD: Oh my God yes. I’ve got a great Bacon.

WALLACE: Did you ever think of doing a full-length autobiography?

BEARD: No.

WALLACE: You should. You’re such a good writer and all of these stories—not just the recollections of Africa, but hanging out with Bacon …

BEARD: Hanging out with Bacon is the most fun of all. And Andy.

WALLACE: Partying with the Stones …

BEARD: Well, the Stones were also great. I was on the Stones tour for quite a while when they did 48 shows. Me and Truman Capote. We went to every single show. Truman had to say, “I don’t really like it.” Bullshit! I was right on the stage. I have billions of photos. And I think I got the best photographs because I took so many.

WALLACE: Are you aware of pop culture today?

BEARD: I’m lazy so I watch a lot of TV. I like it after one or two in the morning. I get 500 channels. I love old movies for one thing. Natural history.

WALLACE: David Attenborough is my favorite.

BEARD: What a legend. Even channel 13. They have Tavis Smiley. He does nice interviews. I always get something from him.

WALLACE: Did you see there’s a new Jungle Book movie out now?

BEARD: Fucking great. The tiger looks pretty amazing. Zara wants to see that. Let’s go see that tonight!

WALLACE: Okay. Do you get a lot of people coming to you now asking you to make sense of it all?

BEARD: No.

WALLACE: You don’t have seekers coming out to find you, the guru?

BEARD: No way! They can’t find it anyway.

WALLACE: That’s true. They’d never be able to get in.

In working himself up to describe his near-death experience at the sharp end of a rampaging elephant in Zara’s Tales, Beard quotes Blake—”You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough”—and then lays out an astoundingly apt manifesto, one he certainly seems to have obeyed. “So keep on jamming,” he writes, “if for no other reason than to thicken up your one and only life, adding texture and bulk to the daily/yearly calendar, and possibly even coming up with something new. Yes, if you crave something new, something original, particularly when they keep saying, ‘Less is more,’ remember that I say: Too much is really just fine. Only by going too far can we break the boring mold and stumble into something a little different. Originality is a key goal for the old human nervous system … The biggest and best homework assignment in life and art, and I’ll give it to you right now, is to keep yourself excited, going forward, happy, enthusiastic. Look it up in a large etymological dictionary (even if you think you know what it means): “eagerness, warmth, fervor, zeal, ardor, passion, devotion, having a god within.”

Beard himself may well have some sort of god within. Maybe also a devil. He is astoundingly enthusiastic (always has been) and, it should be mentioned, really good-looking. Almost cartoonishly so. Always has been. And if that weren’t enough to charm the gods, then his actual, irrepressible charm and enthusiasm surely would have done the trick. He has put a lot into life (still does), and it has responded in kind (still does). Beard has lived fast and fully, with some of the fastest and fullest to have ever done it. He has definitely gone too far and broken lots of molds. Thrice married (to Minnie Cushing, to Cheryl Tiegs, and now to Nejma Beard née Khanum), three times as close to death as the ferry gets without crossing over, he has seen oceans of fame and fortune and originality. And he’s just fine.

WALLACE: Have you done a good job of doing more than enough, in filling your life and nervous system with originality?

BEARD: No.

WALLACE: No? Do you feel like there is something you’ve missed?

BEARD: If you’re into collage, you’re an escapist. I did old master drawing. I pulled off a couple, but it’s very difficult to do. If it wasn’t doable, I didn’t do it. I only ever did things that were easy. This is a lazy man’s thing.

WALLACE: Do you think you’re an escapist?

BEARD: [laughs] I think so!

WALLACE: Well, you do have a chapter in your book called “On the Run.”

BEARD: It’s an escapist thing because it doesn’t tell you anything, does it? But I kind of like it when the years pass by.

WALLACE: It doesn’t give you a great sense of accomplishment to look back at all?

BEARD: I am liking it right now. I really like the way this came out, by the way. It’s not great, but it’s kind of perfect. It appeals to my … thing.

WALLACE: Do you have a particular moment that you like to look back on? Were there great golden days?

BEARD: Absolutely and there’s wonders. I’d like it to feel that way. Here is Michelle Phillips …

WALLACE: You run around with Iman and Jerry Hall and Cheryl Tiegs and Michelle Phillips …

BEARD: The wonderful Beverly Johnson … It was a long time ago. This is a friend of mine getting hit by a rhino. This is Zara’s first picture, inside Nejma’s womb. That’s 96th Street and Park Avenue with the tulips in bloom.

WALLACE: You grew up on the Upper East Side …

BEARD: Well, I didn’t grow up. [laughs] But I have some memories from that period: 133 East 80th Street at Lexington Avenue. It goes downhill opposite the church. I was coming home one day and this guy on a bicycle got run over by a coal truck. This was when I was a very obnoxious person. My mother heard and she was yelling out the window, “Come home, get away.” His head was just all down the street, a child’s dream. That was the first murder scene I’d seen.

WALLACE: How old were you?

BEARD: It was probably 1950.

WALLACE: So you were 11 or 12?

BEARD: Now you see this came up rather nicely. You get things that are just easy.

WALLACE: You dated it with the football games you were watching. Did you play sports?

BEARD: I did. I used to box in England.

WALLACE: What? How? Why?

BEARD: I was in an English school. This is one of the pages I was trying to get you. That’s Bacon doing me. That’s my neighbor, for Interview.

WALLACE: Jackie O? Wow.

BEARD: Yeah. It was with Lee [Radziwill] … Caroline [Kennedy] … Jackie was here quite a while. It all started in my first marriage to Minnie Cushing.

WALLACE: One of my favorite revelations in the book is when you realize that the diaries themselves are the artifact. They’re not in preparation for something else, but they are themselves the artwork. So when you think of what it is that you do, what do you consider yourself? A painter, a writer, a photographer?

BEARD: I’ll leave it this way … Do you know about how many times I’ve thought about it? I don’t think anything. You do the best you can.

WALLACE: Are there certain things that you’re the most proud of?

BEARD: I really like all of the diaries. It doesn’t have anything to do with anything but the enormous amount of pages and the fact that they dribble on.

WALLACE: That’s what I imagine a brain would look like. And those are all of your memories. It’s all of your time turned material. I have an almost fetish relationship with diaries. I love the writing on these pictures. Like, the actual handwriting. I love the aesthetics of a diary. I love looking at writing on a page.

BEARD: I felt it was a little inappropriate, but I liked it for that reason.

WALLACE: Are your memories the ultimate pieces? Do you feel like your life itself is the work of art?

BEARD: I don’t even like the word frankly, but I think the nicest things are self-made. If you rip it all away and you learn how to set it up …

WALLACE: Huh. You’re sort of an existentialist. As in, what you do is kind of what you are.

BEARD: It’s funny you say that because I’ve been watching this show about God [The Story of God With Morgan Freeman]. That wonderful actor, Morgan Freeman, explores what God is. It’s what the Masai carve. It’s what people have at Halloween. It’s many things. We’ve got God in many forms but…

Beard’s masterwork, The End of the Game, is subtitled The Last Word From Paradise, and the painful irony is that conclusive statements seem to be primarily what now elude him. He searches through memories and ideas dimmed by a recent series of strokes, looking for last words in vain. But somehow he is remarkably unflustered by it. Stammering after some reference, some word or thought or hoary old name, he will, at times in our day-long chat, give up, cross his arms, and smirk at me as if to say, “Well, what are ya gonna do?”

At my insistence—though he would like to continue on—we take several breaks, to get sushi, to watch TV, to gossip, and to walk around his property. At one point I show him my journals, covered in my tight geometric-looking handwriting. “You’ve got some German in you,” he says. His script, on the other hand, is winding and sinuous, like enchanted grape vines laid flat, embellished here and there by lurid blooms of blood, paint, who-knows-what.

At sunset, we clamber down the sea stairs to watch the sky turn a golden pink. The wet stone beach where the cliff side has fallen in looks like a slippery stack of potatoes in coral, mustard, mauve. We both struggle with our footing, and as we sort of loaf there, with the tide encroaching, talking about aging, I am struck that Beard seems to be somehow set apart from or outside of time. His is a 1950s, politically incorrect vernacular, to be sure. But one he manages to use to argue the case that we are entering into a new era of Expressionism, adding a glowing and wildly progressive-sounding paean to the transgender movement. His life and body of work, it seems to me, might have fit as neatly into the original Expressionist era as they do now, and still they seem ahead of their times.

But what does place him, firmly, into the second half of the 20th century is his position within a chain of explorers—from Blixen and her pals, through to Dan Eldon and others—and his portrait of a natural world in chaos. Much of The End of the Game was written and photographed while Beard was working for a warden in the Tsavo National Park in the mid-’60s, but its message is as screamingly urgent and poignant as any work, in any medium, to be made about man’s destruction of his natural habitat since. The only thing that has changed is that the world Beard documented more than 50 years ago is gone and is not coming back.

WALLACE: When I was a kid, I remember being so fascinated about the stories of explorers, like Richard Francis Burton or Henry de Monfreid.

BEARD: I never heard of him.

WALLACE: He was amazing. He was born in the South of France and knew Gauguin as a kid. I think when he was 14, he stole a boat and ran off like Rimbaud. Eventually, he started running guns and hashish into Abyssinia.

BEARD: Fucking A. I’ve got to get into this.

WALLACE: This guy is amazing. Then I really fell for the world of Paul Bowles, the Beats …

BEARD: All the ones that ended up in the worst areas of North Africa were great. I’ve got one of their things upstairs.

WALLACE: Well, you knew Burroughs.

BEARD: Yes. We did a whole thing with him.

WALLACE: I have a picture of you with Burroughs and Nic Roeg …

BEARD: Nic Roeg is a very nice person. Yeah, that’s us.

WALLACE: Not a very good picture, but you get it. Do you think of yourself as part of a school?

BEARD: [laughs] No way! I’d hate that. But, you know, I used to do a lot of work with Interview, and I had a lot of fun up there.

WALLACE: But you’re not a pop artist at all.

BEARD: No, but I like them all. Everybody was there. Everything was easy.

WALLACE: Do you think other artists work harder than you do?

BEARD: I didn’t think of it as hard. I thought of it as like …

WALLACE: A really messy hobby?

BEARD: Why not?

WALLACE: No, really. Do you think of it as a compulsion, your need to work, to collect, to collage?

BEARD: I did whatever I was attracted to. I could always get anybody to do good pictures. Photography is really subject matter. That’s the way I would say it. So if you can just somehow set the scene … I’m glad to show you a couple of those. The blond with the blood on her? That’s unique I think. It’s not easy to make that.

WALLACE: That’s what I am saying. I think you are too modest. You should be proud of what you do.

BEARD: I am proud.

WALLACE: Good. Do you have any regrets? Is there anything you look back on and go, “Shit”?

BEARD: I think, “What’s the point?” Of course I have lots of regrets, but there’s no point in hanging on to it. There are lots of portraits I’d like to have done—all kinds of things. But I’ve got a lot in there. I’ve actually done all right.

“PETER BEARD: LAST WORD FROM PARADISE” OPENS THIS SATURDAY, JUNE 18, AT THE GUILD HALL MUSEUM IN EAST HAMPTON, NEW YORK. FOR MORE ON BEARD, VISIT HIS FACEBOOK PAGE.