art

How Quaaludes Brought Durk Dehner to Tom of Finland’s Attention

Photo by Abi Benitez.

It’s not common to take one’s seat at a dinner table and find the napkins adorned with a cock ring. During any other dinner celebration at The Standard Grill in the heart of New York City’s Meatpacking District, this rather unconventional motif would’ve scared off guests. Except when the honoree is Tom of Finland. The juxtaposition of the pristine napkins, rolled into a phallic shape, cradled by the kinky toy served as a nod to the legacy of the late artist Touko Laaksonen (Tom of Finland’s real name), putting erotica in places where society deems it lewd or unfit.

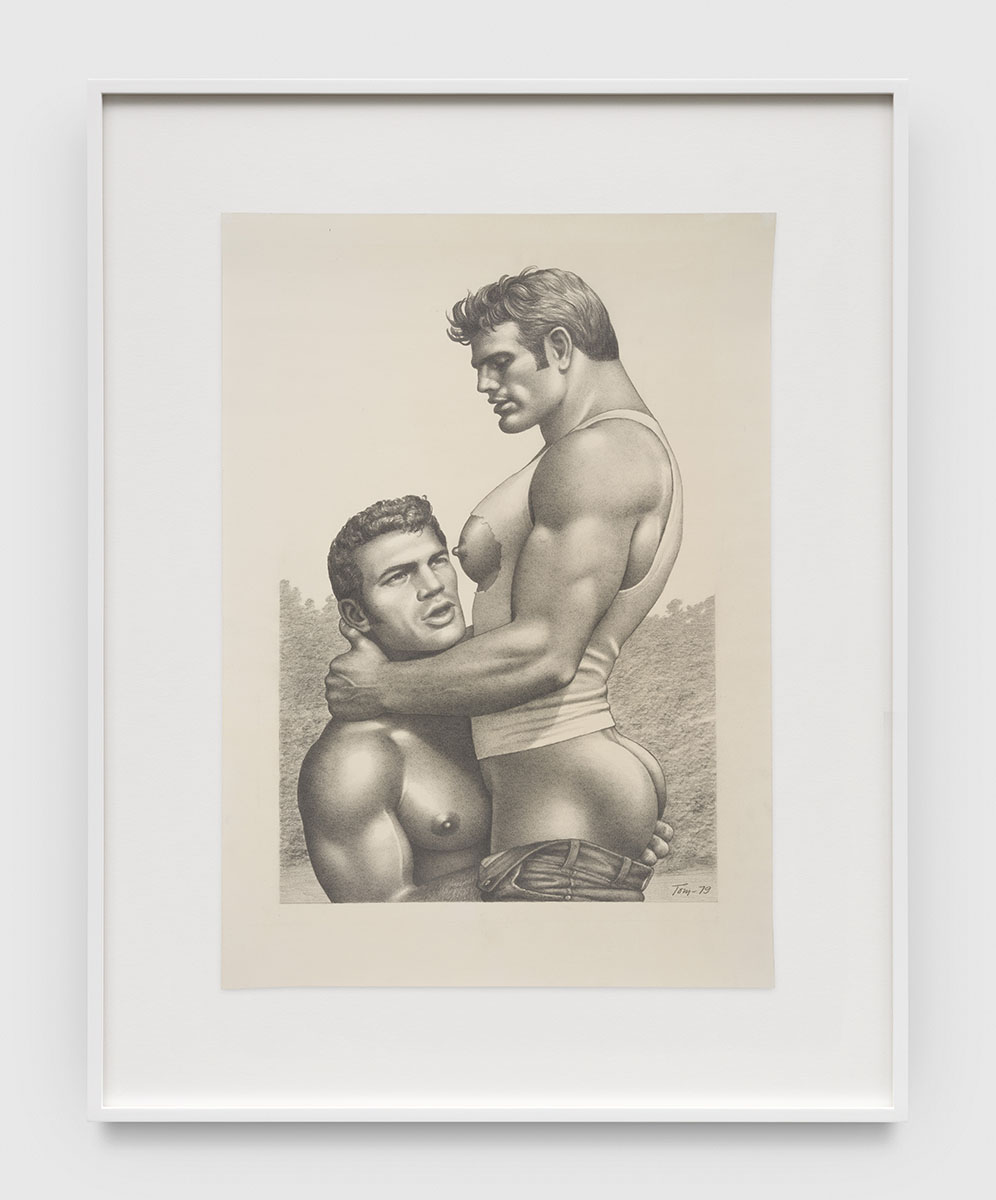

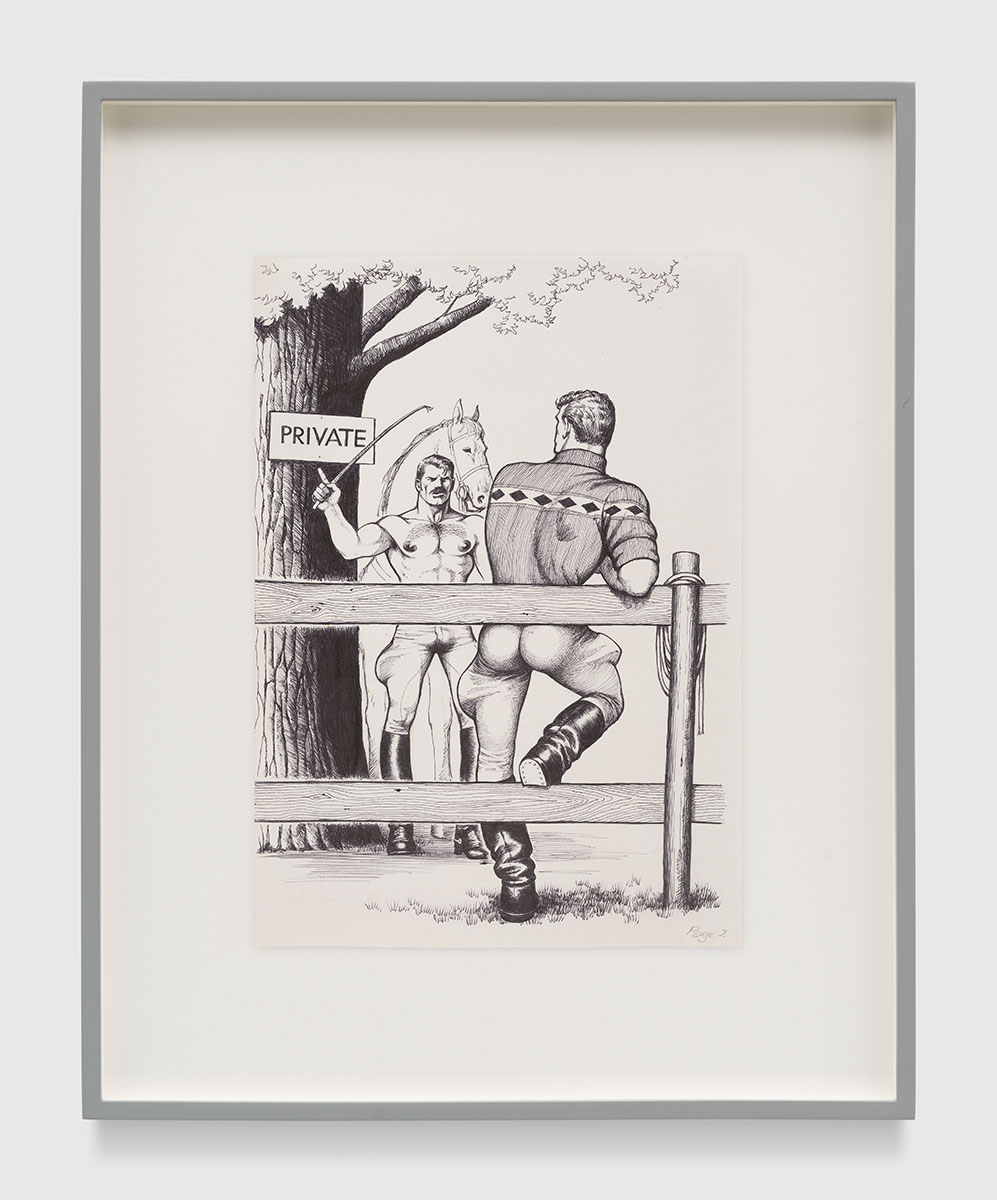

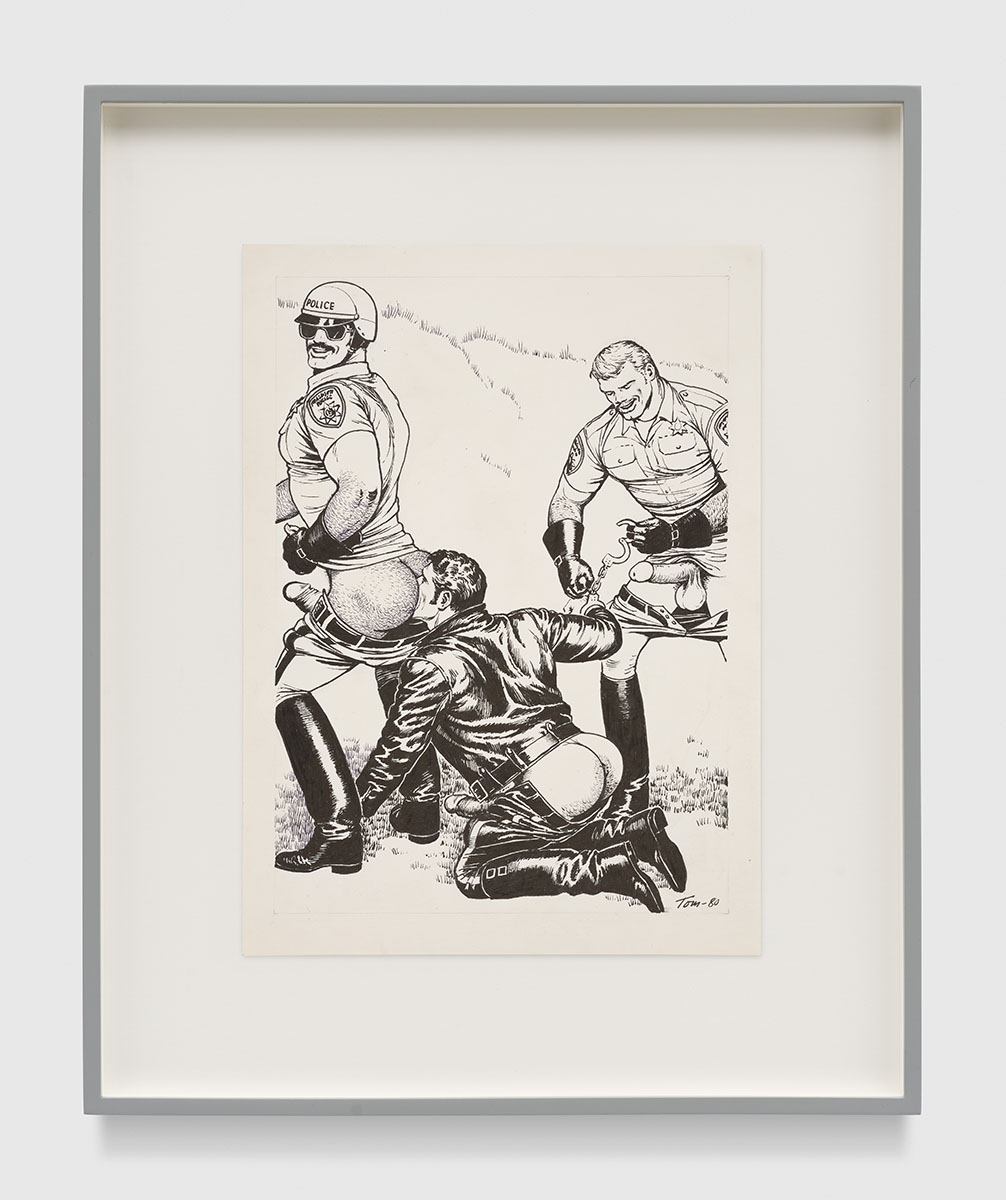

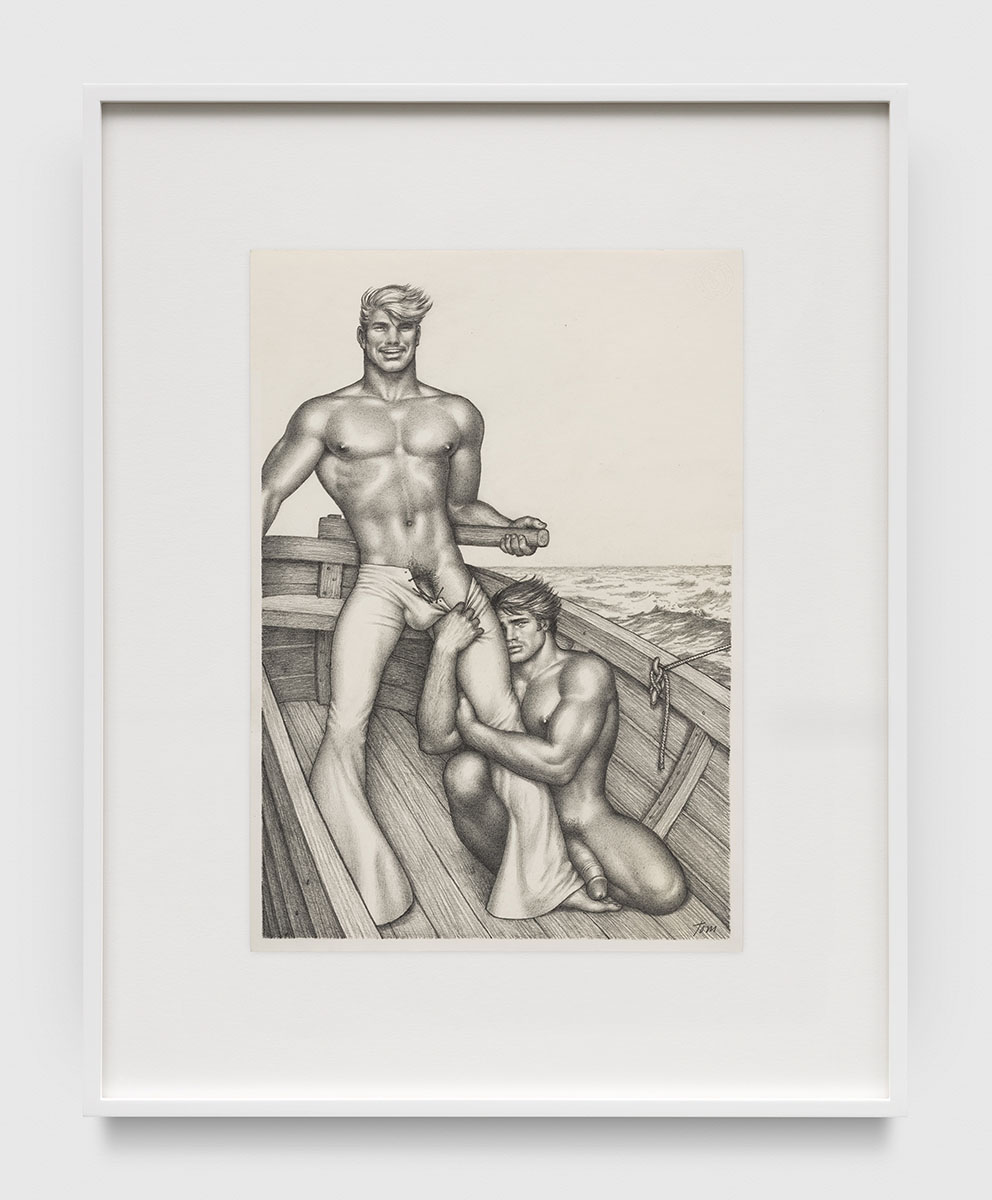

Through February 25th, the David Kordansky Gallery, in collaboration with Tom of Finland Foundation, is exhibiting some of Laaksonen’s rare drawings, from Kake vol. 21 “Greasy Rider” (1978) to vol. 22 “Highway Patrol” (1980), part of a larger body of work comprised of erotic graphic novels that he created between 1968-1986. On the night of the opening of Tom of Finland: Highway Patrol, Greasy Rider, and Other Selected Works, fans of all ages clogged the streets of Chelsea to catch a glimpse of Laaksonen’s art. Some, like Durk Dehner, a collector of Laaksonen’s work and the president and co-founder of the Tom of Finland Foundation in Los Angeles, were appropriately clad in tight leather. Prior to the after party at the Boom Boom Room, hosted by Susanne Bartsch, I had a brief moment with Dehner, during which he reminisced about the first time he encountered Laaksonen’s work—at a leather bar, no less—and talked about why it remains crucial to gay liberation.

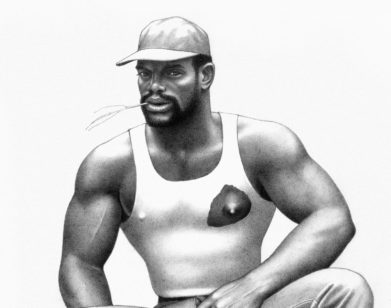

Photo by Luisa Opalesky.

———

ERNESTO MACIAS: So, you first saw Tom’s drawings at a bar?

DURK DEHNER: I saw this drawing on the wall and it was for a motorcycle run, and what you did is you tore off the phone number and then you called the phone number and they would tell you where the run was going to happen. All the phone numbers were torn off, so I felt like I was not doing anyone a disservice by taking the flyer. It had this kind of magnetic pull on me and I didn’t know why. So the next day, because I’d won a leather contest at the Eagle’s Nest, which was the next bar up the street—I had a mentor, really a leather mentor, and his name was Louie Winegardner. And he was actually a composer and some of his music was played by the New York Symphony.

MACIAS: Oh, wow.

DEHNER: He lived in Hell’s Kitchen in an apartment that was completely black with no windows—the windows were painted over black, and all he had was a very long, gothic table with two gothic chairs on each end. And he was a real masochist. It was very natural for me to be able to dominate him, but he got me to enter this contest and he gave me a Quaalude, which really de-inhibited me.

MACIAS: How would you describe the feeling of a Quaalude?

DEHNER: If you had inhibitions, it would liberate you. You didn’t care. You just did what you felt like doing. And very self-confident. So I raised hell in that bar and, of course, I got everyone participating. I ended up winning and Ken Hack saw me there, he’s a fashion photographer and he gave me his card and said, “Call me.” I called him and I did some photos for him, and then he turned me over to Bruce Weber. Bruce and I have stayed friends all these years.

MACIAS: That’s amazing. Do you have the photo he took of you?

DEHNER: Yeah, I do. Then I got a photo session with this male studio called Target Studios because of winning that contest. I met another erotic artist there and I pulled out the drawing, I said, “Do you know who this is?” and he went, “Oh, yeah, that’s Tom of Finland.” He said, “Do you like it?” I said, “I do like it, but a very strange thing happened to me. It had this kind of magnetic pull on me,” and he says, “Well, I have his address if you want to write him.” So I wrote him a letter and, of course, I complimented it, but also I told him about having this experience which I’d never had before. He wrote me back and we sort of became pen pals.

MACIAS: How long did that last for?

DEHNER: Well, that was in 1976, and in ’77 he wrote me and said, “I’m coming to Los Angeles and it’ll be my first trip to America because I have an exhibition in San Francisco and L.A.” I said, “Well, why don’t you let me be your host?” And he said yes. He had been seeing me in magazines because of Bruce using me, and there was a book called Looking Good, and it was sort of being promoted. Anyway, he came to America and he was hoping it might be me because I never sent him a picture, and it turned out to be.

MACIAS: And the rest is history.

DEHNER: Yep.

MACIAS: Thank you so much for sharing that story with us. That’s really great.

DEHNER: What happened was that I got to witness being at an event with him where guys would line up in a row to shake his hand and tell him how much they appreciated what he had done for them, and this happened over and over again.

MACIAS: In what sense?

DEHNER: He gave them an opportunity to have an identity that they didn’t see was available before. So they used that, and grew into that, and became that, and felt free, positive, self-confident, and not ashamed.

MACIAS: Not ashamed to be who they are.

DEHNER: And so having heard that many, many times, I realized that I had a purpose, and the purpose was to be of service to him, to be valuable. To see if I could fulfill for him things that he had not yet had, that he desired. I just found out what those were and then made it happen.

MACIAS: Now we’re here celebrating his work.

DEHNER:: I have to say that before that I had thought about killing myself because I didn’t see the value in being here if I didn’t have something that was bigger than me. I couldn’t find it. I didn’t realize this at the beginning. This is age, and looking back, and seeing what happened.

MACIAS: Thanks so much for sharing that. Honestly, that experience that you had, that revelation, so many people have it. I had it looking at those pictures and drawings, and so many people will have them.

DEHNER: Exactly.

MACIAS: Whether it looks exactly like his pictures or not, it doesn’t really matter. It’s about freedom.

DEHNER: You know what? His work communicates that everywhere. I mean, everywhere. It doesn’t matter about your ethnicity or your sexual orientation. They still read it. He gave us an understanding that having sex was natural and that it was out in the sunlight. We could celebrate that.