How Ethan Greenbaum Sees the City

Mundane details of infrastructure are overlooked by most New Yorkers–unless, of course, something goes wrong. Yet the evidence is in plain sight–scrawls on the sidewalk indicating piping or wiring underneath, lane delineations, fleeting views of Tyvek sheets–quietly signaling urban construction and upkeep.

A childhood spent between rural New Jersey, Virginia, and Florida helped give artist Ethan Greenbaum a fresh outlook; New York, through his eyes, is teeming with the subtle, inevitable, and essential components of modern city life. In his 10 years here, his focus has shifted away from abstract painting toward these elements, and he appropriates them for semi-abstract works often employing industrial-grade equipment and materials. He’s perfected a technique in which he crystallizes photographs of sidewalks and other city surfaces on PETG (similar to plastic) using vacuum form machines–”vacuum form paintings,” for short. Lines and other marks in the images tend to determine the shape of the final work.

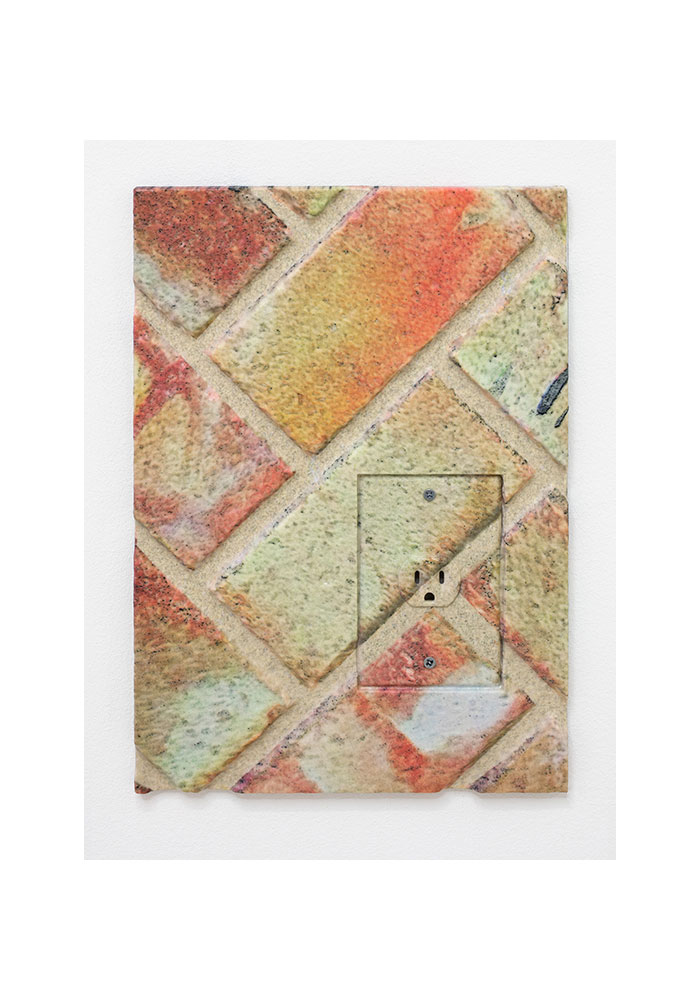

More recently, he began working with 3-D powder printing. For these pieces, he generally takes patterns from industrial materials, like wood board, foam insulation, fake bricks or stone, and projects them on to 3-D-printed flat objects. Some feature three-dimensional details like outlets and vents; others resemble flat tiles displaying material-as-motif.

For his first solo show at East Hampton’s Halsey McKay Gallery, Greenbaum juxtaposes a new series of 3-D powder prints and larger-scale vacuum form paintings. The title of the show is “Chambers,” after one of the subway stops near his apartment, although Greenbaum also considered how it doubles as the Latin word for camera, referencing the camera obscura, one of the modern camera’s predecessors. “I like the idea of locating it to some street,” he says. “But it’s also this word linking back to the architecture around the camera.”

Right now, Greenbaum is preparing for his second solo show at Kansas Gallery in New York, and an upcoming collaboration with Half Gallery’s Exhibition A. We connected with him over the phone.

RACHEL SMALL: Let’s talk about how the show at Halsey McKay came together.

ETHAN GREENBAUM: The show is two bodies of work: I’ve shown the vacuum forms consistently for a while now and the 3-D prints I’ve been showing intermittently. I was interested in making a stronger connection between the two. The vacuum forms are based on photos I’ve taken of sidewalks and ground planes. I got into it because I liked that they were this primary surface that any kind of construction is dependent on. They’re this kind of skin that, on one level is dead-end, flat, opaque, but also very infrastructural. It’s like the skin between structures, above and below.

SMALL: What attracted you to those surfaces?

GREENBAUM: It became something that I noticed when I moved to the city. Everything I was seeing was this bare minimum for anything else that followed. I remember being struck and almost overwhelmed by the fact that A: everything was built, [as opposed to] areas where things are unplanned or grow through natural systems, and B: that [these marks] were kind of the beginning points. Within that, coming out of a painting background, the metaphor was kind of irresistible–[seeing] those rectangular shapes, monochromes. I’ve been looking more at different orders of marks on the surfaces–like crosswalk markings or lane divisions alongside spray painted scrawls that are meant to indicate infrastructure.

[Regarding] the ways the two [bodies of work] link up: In the case of the photos of the sidewalk mark-making, those are abstract forms that are indicative of things in front of or behind them. That big triangular guillotine blade piece I had [PEAK, 2015], that’s a segment of a lane divider between areas where people on bikes and people in cars are supposed to be; it’s a fragment where the divisions of the graphics decide the boundaries of the composition of the work. Then the [red] marks are infrastructural markings where electrical piping is underneath the surface. I like the idea that it’s this site of multiple contradictions.

That idea of mark making is one of the connections, in my mind, to the 3-D powder prints, in which I focus on things like logos and outlets. There’s some metaphor: Things like an outlet or an air vent are basically abstractions in the sense they’re not really anthropomorphic forms. It’s not like a door handle or even a key in a lock. They are only accessible by way of other machine parts. They’re just conduits for energy.

SMALL: It’s interesting how viewers are forced to consider something like that as just an object when it’s worked into an art context.

GREENBAUM: Yes. The logos were coming from a similar impulse where I was seeing all these buildings going up around the city covered in different wraps. I was struck by it, and I think it’s visually strange that the way people apply them was indifferent to orientation or legibility. Which, again, is like the sidewalk–there’s no up or down. I like that there are these wraps that are totally functional. If you removed all the graphics it’s just material.

SMALL: Also, the logo functions as advertising, but it also helps the people building whatever structure. It’s like a pattern that indicates the function of a certain thing.

GREENBAUM: That’s exactly the kind of thing I get excited about—a mix of structure and symbolism. I also love that it gets covered up. There’s hidden graphic designs in the core of buildings, often covered up by another form of symbolism, like fake rock.

SMALL: I’m looking at the work now. Is there a pen scrawl on it?

GREENBAUM: Yeah, that’s my signature. That’s me having a little fun with it.

SMALL: What’s the 3-D print with the Pink Panther on it?

GREENBAUM: That’s Foamular, a brand of insulation foam. The Pink Panther, it’s another character, which is a logo. It’s the same play with legibility and recognition. And the material gets sandwiched in between layers of building material.

SMALL: Also who thought, “I’ll make this insulation foam more fun by putting a cartoon on it”?

GREENBAUM: Yeah totally. It’s even better to think about the Pink Panther being buried underneath the floor or something, right? Like, smiling away through the innards, underneath the wood.

SMALL: Like, buried alive.

GREENBAUM: [laughs] Yeah, totally. You can get dark; it’s okay. I made that exact connection in my mind, the face behind the wall. I do like that idea of kind of like another kind of presence.

SMALL: You studied painting in the MFA program at Yale. Do your paintings relate to what you do now?

GREENBAUM: I was actually doing vacuum forming in grad school. I was working a lot in the architecture department. I stopped doing it for a while because I didn’t have access to the vacuum form machines. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. But it came back when I [started] photography. At a certain point, I realized that that [alone] wasn’t layered enough…I like things to be a little more representational than literal, or at least more layered to combine the literal and representational.

SMALL: Do you remember where you took the original photos for the vacuum forms?

GREENBAUM: It’s usually more accidentally, just along routes that I’m traveling. I guess I’m a little turned off by the idea of being too active in the search. I like to be surprised by place, you know?

SMALL: And that keeps the anonymity of the source intact.

GREENBAUM: These are things that are ubiquitous…

SMALL: …you can’t trace it back to its original source.

GREENBAUM: I think that comes out of me having been an abstract painter for a while. It suspends linearity in terms of subject matter, typically. Usually, it suspends a few possibilities and keeps them in motion rather than providing a more linear entry point. I’m trying to do other things to keep [my subject matter] in a space of abstraction, which is a little more open ended.

“ETHAN GREENBAUM: CHAMBERS” WILL BE ON VIEW AT HALSEY McKAY THROUGH AUGUST 3, 2015.