What’s the Polish Word for Art?

Ruslan Trusewych, “This Is the Way the World Is,” 2008. Image courtesy of Cleopatra’s.

Cleopatra’s was born from a walk in the rain for a cup of coffee.

Bridget Finn, a 25-year old archivist at Anton Kern Gallery in Chelsea, tells the story over a glass of wine. We’re at the Greenpoint apartment of Bridget Donahue, the 28-year old director of D’Amelio Terras. The other two young women who make up the foursome behind Cleopatra’s—a new nonprofit art space in Brooklyn’s Greenpoint area—are Erin Somerville, a 26-year-old associate director at Andrew Kreps, and Kate McNamara, 27, the only one of the four who doesn’t have an office in a commercial Chelsea gallery—she’s a curatorial assistant at P.S. 1, in Queens. The others call her the Non-Profiteer. The profiteers and the non-profiteer sip their drinks, nodding and smiling at Bridget Finn’s telling, having surely heard it many times over. They seem to enjoy it all the same.

She had gone for coffee one morning when she stopped at the storefront studio of the painter Andrew Guenther, on Meserole Avenue. “So I was standing in the rain, staring at the window, having quite a weird moment with myself,” Bridget says. “And then [Andrew] walked up. I told him I was fascinated by the space. He said, ‘I’m packing my stuff right now.’ He was moving out.” She pauses. “Immediately, right there, I said, ‘We want it.'”

The funny thing was, there was no ‘we’ yet. “Kate had no idea who any of these people were at this point,” says Bridget Donahue, who was in Los Angeles for the first of Matthew Barney’s “Ren” performances when she received a call from the Bridget in Brooklyn. They were friends through the gallerist Anton Kern. Donahue then called Kate from LA; they had met at the Hessel Museum at Bard College—”We bonded over Rosemarie Trockel,” Kate says. At the same time, Bridget Finn called Erin, who she befriended at a Ned Vena show. All four are connected by art. And right from the beginning, it was all-in.

“We all sort of showed up to this 10-year lease,” Kate says. Erin agrees, “Kate and I ended up in the most perfect arranged marriage.” The upside to a long lease is, of course, the long leash it gives Cleopatra’s, creatively. “When we conceive of the projects,” says Donahue says, “the longevity is built into our mindset.” Kate adds, “All the projects leave a residue. We’re building an archive.”

Bridget Finn; Bridget Donahue

It’s easier to build something when all four live within a 15-minute walk of 110 Meserole. “We’re not a Williamsburg gallery,” says Erin. “Which is a very defined thing at this point.” Nor are they a Lower East Side gallery, and most certainly not a Chelsea gallery—all more or less definite articles. Cleopatra’s is still very undefined; they only “opened” this past July with a text piece by Tyler Coburn, which appeared in the October issue of The Journal. Approached by editor Michael Nevin, who wanted to do a piece on Cleopatra’s, they did something unusual: they turned it down. Instead, Cleopatra’s and Coburn collaborated with The Journal on a set of artist multiples, in lieu of a story. The result, WL14/TC08, was a piece of hopelessly cryptic text that included the words ‘Greenpoint’ and ‘Cleopatras,’ but hardly anything else identifiable or sequential, except to those acquainted with Cleopatra’s personal biography. (If you are, there’s no short supply of inside jokes.) Of course, the four were enormously pleased with this nonconformist bit of publicity. (The only problem was getting enough copies. “I broke down and bought one the other day,” Kate admits.)

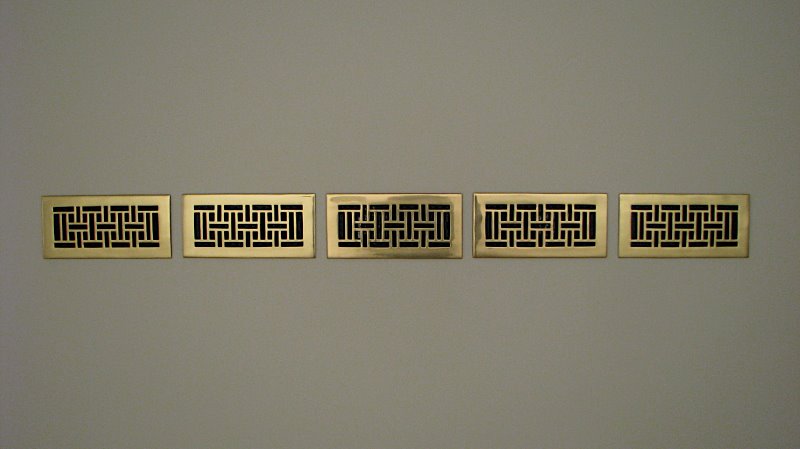

If that was a declaration of creative intent, then Zak Kitnick’s project, Ode to Joy, installed at Cleopatra’s in October, contributed further to the evolving definition of the Cleopatra’s space—and doubled as decoration. “The timing was perfect,” says Donahue. “The space was so raw. Zak’s checklist was basically 17 items of home improvement.” Kitnick took materials purchased and salvaged from shops and homes in the area, then grafted them onto the bare walls and windows of Cleopatra’s: everything from cross-hatched window blinds—a lo-fi allusion to Jean Nouvel’s Arab Institute in Paris—to red oak coverings for the wall outlets, half of which don’t even work. It is an ironic indictment of the upper-middle-class lust for home improvement, but it also gives the place an identifiable look, which it lacked.

Kate McNamara; Erin Somerville

The ever-changing identity of Cleopatra’s is something dear to these four co-conspirators. “The easiest thing would be to have an artist inhabit or install in our space,” says Donahue. “But then what are we left to do?” Because they are in Greenpoint—a gruff, salty Polish neighborhood yet unmolested by the commercial art scene—they have no preconceptions, no expectations. They don’t have a gallery model to follow. They simply have a lot to gain, and only a little to lose.

“We want to find ways to truly collaborate with artists,” Bridget says. “In which case we all lose a little bit of our identity.”

Their loss, our gain.

Zak Kitnick, “Forwards and Backwards,” 2008. Image courtesy of Cleopatra’s.