PARADIS ICONS

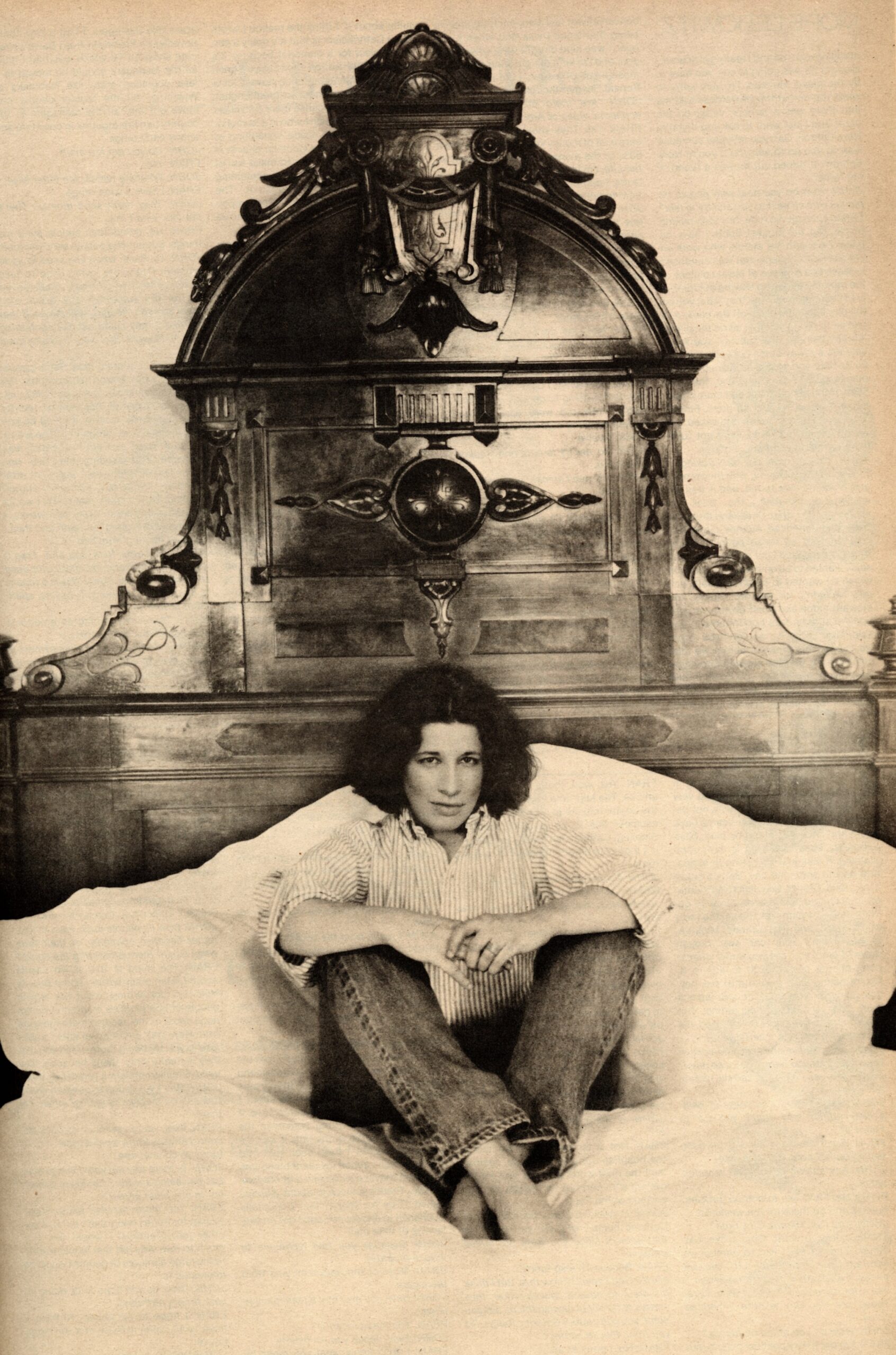

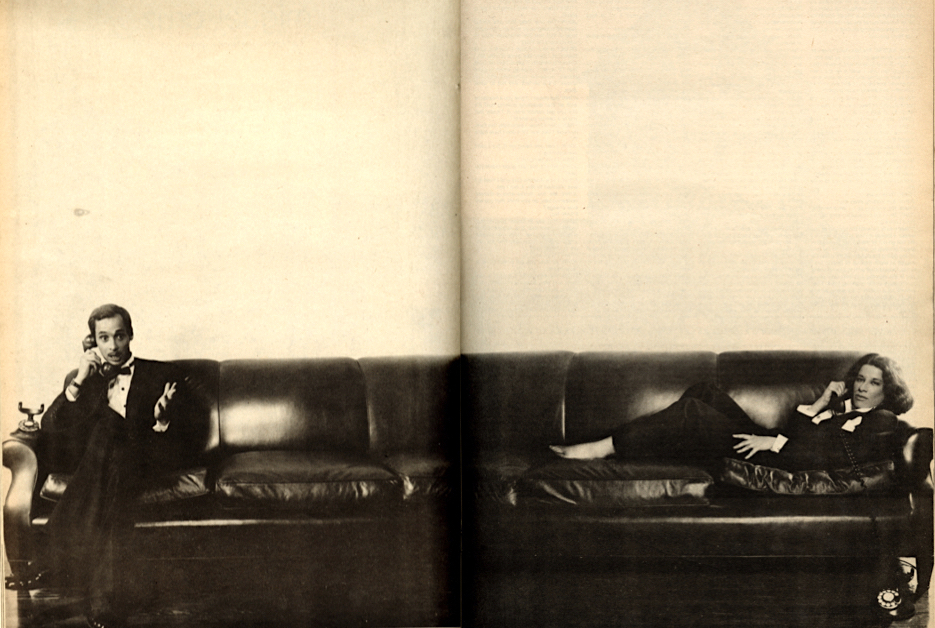

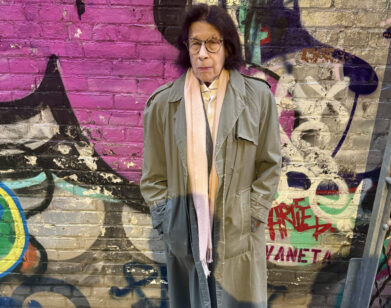

A Taste of Paradis: Fran Lebowitz, in Conversation with John Waters

Over its 258-year history, Hennessy has pioneered and elevated the art of cognac, a spirit fit for kings and queens.

Interview hasn’t been around quite as long – just 54 years – but we like to think we, too, have curated conversations and photography that aspire to a similar level of elegance and sophistication. In honor of Hennessy’s storied Paradis marque, we poured through the Interview archives to recirculate conversations with personalities, entertainers, and icons who personify the brand’s spirit of refinement, grandeur, and artistry. Today, we revisit the September 1981 issue, in which the famously opinionated Fran Lebowitz sat down with John Waters to discuss her reading habits, feelings about Los Angeles, and her outlandish solution to the problem of teenagers.

———

Eminent film director and unwelcome house guest JOHN WATERS visited recently with well known writer/hostess Fran Lebowitz to discuss the August 31st publication of Fran’s new book SOCIAL STUDIES (Random House $9.95). Mr. Waters asked to be identified as the author of the forthcoming show biz autobiography SHOCK VALUE and since he let himself out of the apartment quietly without awakening anyone, his request has been granted.

JOHN WATERS: The fake Paris Review interview, here we go. I want to tell you I thought Social Studies was funnier than Metropolitan Life. I read it on the train and I was laughing and people were turning around looking at me and wouldn’t sit with me so it served a dual purpose.

FRAN LEBOWITZ: I think probably it’s not unusual that people stare at you and refuse to sit with you, John.

JOHN: Well, usually that’s why I take books with murder titles so nobody sits with me. Just because I was laughing to myself they didn’t sit there. Was it hell to write Social Studies?

FRAN: Yes. It was worse than writing Metropolitan Life, except physically. It was much nicer to write it in a big apartment than it was in a small apartment.

JOHN: How long did it take you to write it?

FRAN: Three years.

JOHN: But working every day?

FRAN: No, working about three months

JOHN: Describe a typical working day for Fran Lebowitz.

FRAN: I really finished the book up in four weeks. I locked myself into the house. I did not go out of the house. My life consisted of sleeping and talking on the tele. phone during the day. It was my usual life except at night instead of having fun I wrote. I would start writing around one or two in the morning and write until about nine o’clock in the morning. I didn’t see anyone for a month, not a single person except the Gristedes delivery boy, who by the third day I was inviting in for drinks.

JOHN: Before, you had said that some times when you’re writing you’d like to talk to people on the phone because it gave you a chance to try out things.

FRAN: Yes, sometimes it does. I like to talk to people on the phone because I would rather talk to people on the phone than write.

JOHN: Do you ever get writer’s block?

FRAN: I have constant writer’s block.

JOHN: How do you get rid of it?

FRAN: When the fear of not doing it be comes greater than the fear of doing it. When I finally get really afraid that l’r never going to be on Merv Griffin again-that’s when I sit down to write.

JOHN: Do you walk around your apartment reading it aloud?

FRAN: No.

JOHN: I always do, that’s why I have to live alone.

FRAN: I read aloud while I’m writing but I don’t walk, I sit there. I read aloud to myself every third word. It seems longer when you read it aloud. You may have noticed that this book is even slimmer than Metropolitan Life.

JOHN: It’s a quick read, that’s good.

FRAN: It’s smaller and more expensive.

JOHN: Don’t you wish you could talk it right into a tape-recorder like Barbara Cartland?

FRAN: Yes, but unfortunately books that you talk right into a tape-recorder read like books that you talked right into a tape-recorder. I think she does the whole thing in one sitting.

JOHN: From beginning to end?

FRAN: Yes. She sits there and she says, “page one.”

JOHN: That is a definite talent.

FRAN: I don’t think she even does it into a tape-recorder, I think she has someone who sits there and writes it down. That’s much more luxurious.

JOHN: When you wake up in the morning do you feel a responsibility to be funny?

FRAN: It depends on who’s here.

JOHN: Do you find it annoying when you go out with people who always expect you to be funny? It’s like putting on the tap shoes.

FRAN: No, because I’m just naturally entertaining. It’s no effort for me to be funny in conversation. It’s an effort for me to be funny in writing.

JOHN: Were you shocked at the success of Metropolitan Life?

FRAN: Yes, but I got used to it very fast. I was initially very surprised but it’s amazing how quickly you can adapt to success.

JOHN: Besides it being a very funny book, what do you think helped make it a success?

FRAN: John Leonard from The New York Times. There’s no one I like more than John Leonard.. The night that John Lennon was killed I was at Diana Vreeland’s party at the Met for the Chinese clothes and Tina Chow came up to me with this really stricken look on her face and said, did you hear the horrible news? I said, what horrible news? She said, John Lennon was shot. I said, John Leonard was shot? Who would shoot John Leonard? I was so upset. She said, who’s John Leo nard? I said, you just said John Leonard was shot. She said, I said John Lennon. And a wave of relief swept over me.

JOHN: So you were relieved. I know Romain Gary died that week and I didn’t notice we had a moment of silence for him.

FRAN: Well I wasn’t exactly relieved. The Lennon murder was horrible but I do think that it’s generally agreed that he was no John Leonard.

JOHN: I see the dedication is in memory of Henry Robbins. Do you think he helped make the book successful?

FRAN: Yes, because among other things he handed it to John Leonard. He took John Leonard to lunch and gave him the book. John Leonard must get every single book that comes out and I don’t know whether he would have ever gotten to read that book otherwise. Henry was an incredible man and a wonderful editor and even though he basically regarded me as some sort of inexplicably erudite juvenile delinquent, I had a very close relationship with him.

JOHN: How did you do in social studies in school since that’s the name of your book? Do you owe anything to the education you received in social studies?

FRAN: No. I owe nothing to the education I received.

JOHN: Me either. I wish I had quit when I was sixteen, I would have made two more movies.

FRAN: After I learned to read I don’t remember learning anything else. I still can’t do fractions. | still can’t do percentages and neither can you.

JOHN: There’s one thing I disagree with in your book that I was going to bring up later, that there’s no such thing as algebra in real life. There was with me when I thought, if you put up this amount of money you’ll get this much back and X amount back if it makes money.

FRAN: That’s not algebra, that’s arithmetic.

JOHN: No, it’s algebra. Like if the whole budget is $100,000 and you put up $10,000, you’ll get X amount back if it makes this much. That’s algebra.

FRAN: No. If the whole budget for a movie is $100,000 that’s fiction.

JOHN: Did you do well in composition?

FRAN: I never did anything. Sometimes I did write. I never got good grades though. In high school I never got any good grades at all because I never did any. thing. I never handed in any work. I didn’t even stay awake. I slept all through school.

JOHN: They just let me read if I’d shut up.

FRAN: They didn’t let me do anything. In high school I was sent about every two weeks to the county psychologist which to me was great because it meant I could leave school and smoke on the way there.

JOHN: And talk about yourself.

FRAN: And talk about myself. No, they asked me weird questions and-mostly I played with blocks. It was like being sent from high school to kindergarten.

JOHN: You didn’t read a lot in high school?

FRAN: Yes, I read all the time.

JOHN: You must have graduated to adult books.

FRAN: I read all the time. I still read all the time – that’s why I don’t write.

JOHN: Can you remember anything you read in high school that influenced you?

FRAN: I can’t think of any writer who I feel directly influenced by. My reading has just been too indiscriminate.

JOHN: Were you ever, and I know this is hard to imagine, a flower or a love child?

FRAN: No. I used to go to all the demonstrations in Washington because they were fun.

JOHN: Me, too, to meet good people. Were you involved in the whole political scene? You wanted the end of the war and stuff?

FRAN: No, I wanted to go to Washington and have fun. I was involved in it as a recreational activity.

JOHN: Would you characterize your work as having a lot of snob appeal?

FRAN: Well, as having a lot of snobism certainly.

JOHN: Were you a snob when you were broke?

FRAN: Yes. When I wrote Metropolitan Life I was completely broke. I’ve never ever, even with the success of Metropolitan Life, had anywhere near the amount of money to justify my snobbery. It’s innate.

JOHN; You talk about poor people a lot in your book and it’s very funny but is there anything you miss about being poor?

FRAN: No.

JOHN: But I sensed a certain nostalgia about being poor from your book.

FRAN: No. I just miss getting the ego satisfaction of people paying for me all the time.

JOHN: But don’t you think the richer you get the more people pay for you? The rich get richer.

FRAN: The richer you get the more you’re around the kinds of places you don’t have to pay for anything. But it’s not the same thing. No one buys me clothes anymore. I like the idea of people buying me things but people don’t anymore.

JOHN: When you go to a film you din’t like do you try to ruin it for people around you?

FRAN: No, I just walk out.

JOHN: I did in Rocky. I thought, these people aren’t going to enjoy this if I have to sit here.

FRAN: I went to see Moment by Moment and enjoyed the fact that the whole audience hated it. That’s the only time l’ve ever felt love for my fellow man in a group.

JOHN: Describe the fact that punks like your work when I would think you would be against the whole punk movement.

FRAN: I have no idea why they like my work. I didn’t notice it at first because at the beginning of all that stuff I was in the house all the time. Finally I went outside and there were all these people who looked like that and they were coming up to me and saying hello.

JOHN: Do you think pirates will like your work?

FRAN: I certainly hope not. Aren’t pirates gone yet?

JOHN: I don’t know.

FRAN: John, the time I saw the most in my life in New York was at your party for your movie.

JOHN: I didn’t invite them.

FRAN: Would you like me to ask you the question, why do pirates like your work?

JOHN: I don’t know. The only time I ever wanted to be a pirate was when I was a kid when you took a coat hanger and put it up your sleeve with a hook on it like Captain Hook. I think some of them are going so far that they would have cut off their legs and put on peg legs.

FRAN: When I see them I long for a gang-plank.

JOHN: The one thing that has always seemed incongruous with your snob attitude is that you like television. How do you account for that?

FRAN: I’m an American. I only like some television. I only like game shows. No, I like real television, it’s true. I like the thing that TV is really good at, which is game shows, situation comedies and talk shows. It’s a perfect way not to write, John.

JOHN: But doesn’t it give you a headache with all that quacking coming out? It’s like you get cancer from it. I know that you’re a cancer paranoid.

FRAN: I don’t know, I especially like “Family Feud.” I like real TV, I don’t have cable TV.

JOHN: I can see being on it, but I can’t see watching it.

FRAN: I love being on it.

JOHN: What’s the last good movie you saw?

FRAN: I saw Atlantic City and I liked it. I was shocked to like it, but I did.

JOHN: Me, too. You’ve always dressed conservatively, do you think that you will ever change?

FRAN: No.

JOHN: You say in Social Studies that you’re a good deal less villainous than popularly supposed. Does that present any problems in your daily life? Are people scared of you?

FRAN: I hope so.

JOHN: At least you get better tables in restaurants.

FRAN: Yes, I get better tables in restaurants and also the only problem that I have is that I almost invariably fight with shopkeepers. When I moved to my new apartment it was amazing to me that I was allowed to shop in places right near my house because I hadn’t alienated them yet. But what happens as the days go on is, I start having to go further and further away to go to the cleaners because I end up having such huge fights with them.

JOHN: You seem to have a fondness for children that many people wouldn’t expect, do you think you’d ever adopt one?

FRAN: No, the word is fondness John, not insanity.

JOHN: How about paying a surrogate mother?

FRAN: For what? I’d much rather have a surrogate writer. In fact, if someone wants to come and write my books for me I will have their baby. I’ll make a deal.

JOHN: Don’t you think it’s very moral that people can buy babies now because they’re the ones that really want them?

FRAN: Yes, I think it’s perfectly fine.

JOHN: You talk a lot about air travel in Social Studies, do you fight with stewardesses?

FRAN: Yes, I’ve had major fights with stewardesses and stewards.

JOHN: Pilots?

FRAN: No. The only time I’ve ever talked to a pilot was a couple of months ago coming back from Paris. The pilot woke me up. When I get on a plane the first thing I do is I issue instructions to the stewards and stewardesses about not being awakened for anything – meals, plane crashes. If the plane’s crashing who wants to wake up? I want to go sleeping. On book tours I’ve been known to take “Do Not Disturb” signs from hotels and put them on top of me with a little note saying, “My seat belt is fasten-ed, I don’t want to eat.” I got on this plane and I announced that I wanted to go to sleep and I went to sleep and somewhere over the Atlantic Ocean someone woke me up. I looked up and I saw the pilot standing over me and I really got scared. I thought he was going to say, you have to fly the plane. He said, I’m very sorry to wake you up but the stewardess told me that there was a famous writer on the plane and I just want to ask you if you’re Nora Ephron. Can you imagine someone waking you up to ask you if you’re Nora Ephron? It turned out he was a friend of her father’s.

JOHN: How do you deal with people on planes who sit next to you and try to talk?

FRAN: I just am so rude they stop talking to me. But the biggest fights I have on planes are with the people who work on planes. Once a plane that was supposed to leave Los Angeles at eleven o’clock in the morning ended up leaving at four thir ty in the afternoon. First they’ll put you on the plane then take you off the plane and just lie to you or you just sit on the plane.

It’s like being in the subway. You know how the subway stops between stations for an hour and no one says anything. On planes no one says anything, they just keep giving people more and more champagne and people just sit there. Finally, on this one flight I got up and asked why we hadn’t left and they were not forthcoming with any answer.

JOHN: They suspect you of hijacking.

FRAN: So I kept arguing with the steward and he came over to me, and it was the weekend of the ABA, the book con. vention in LA that weekend there had been that American Airlines plane that crashed with all those people coming from Chicago, and I got off the plane and said I wanted to be on the American flight which I’d wanted to be on originally and they wouldn’t let me off. Finally, the steward came and knelt down – a position I’m sure he was comfortable in and said, Miss Lebowitz, wouldn’t you rather we caught this problem before we took off? I said, is that the choice? Either you leave six hours late or you crash in mid air? Why don’t you put that in your ads instead of the steak. And Dionne Warwick was on the plane and she was sitting in front of me and she was behaving very well as opposed to me who was not behaving very well. The steward came back again and knelt again and he said, Miss Lebowitz, Miss Warwick is not com-plaining. It was just like being in school and having someone say, Betty’s being nice. I said, Dionne Warwick hasn’t worked in six years, she has no place to go. Then finally he came and he said to me, I don’t understand this attitude, Miss Lebowitz, hasn’t your car ever broken down? I said, yes, but you know what? I don’t charge people $900 to ride in it. You’re acting as if you said to me, hey, you going to New York, do you want a ride? This is a scheduled airline. The ticket cost a thousand dollars and it’s supposed to leave at a certain time.

JOHN: Do you have any special places in New York that you hang out these days?

FRAN: Not really. I have certain restaurants I like to go to.

JOHN: Since you’re a successful best selling author why don’t you go to Elaine’s?

FRAN: Because I’m a successful bestselling author and I don’t have to.

JOHN: Any tips on out-of-town vacation spots?

FRAN: No, I just like to borrow peoples houses and go there for the weekend.

JOHN: You like Atlantic City, right?

FRAN: I love Atlantic City, I like Las Vegas. First of all, I like to gamble so naturally I like Atlantic City and I like Las Vegas. I also like it for other reasons. I like it for its architecture, for its culture. Those are my two favorite American cities.

JOHN: How do you stand politically?

FRAN: I’m not a very political person, but I am quite conservative.

JOHN: Who did you vote for?

FRAN: I voted for…I can’t think of his name anymore. I voted for Ed Clark. I voted for the anti-tax. I’m very financially conservative. I feel completely justified in being that since I was that when I was poor. I was kind of right wing when I was poor and l’m kind of right wing now on all those kinds of issues. I did not vote for Ronald Reagan though.

JOHN: Are there any cures for the economic woes of America?

FRAN: Yes. They should let people who earn a lot of money keep it all. I gave them 60% of the money I made on Metropolitan Life. I’m in favor of anything that cuts taxes. I don’t care who they take it away from to tell you the truth.

JOHN: You should go over to some welfare people’s house and ask for dinner once a week.

FRAN: The thing I’m most opposed to is government funding of the arts. I don’t want one cent of the money I earn to go to a ballet dancer in Ohio.

JOHN: Or a mural. How do you feel about inner city murals?

FRAN: Not one penny. I would much rather that we bought helicopters and things like that. They never gave me a penny. I didn’t see any money coming around here when I didn’t have any and they’re not going to get any of mine.

JOHN: How old were you when you started smoking cigarettes?

FRAN: Twelve.

JOHN: Do you try to bate non-smokers?

FRAN: No.

JOHN: You don’t smoke on elevators and stuff? I do.

FRAN: I very often walk into an elevator with a cigarette. I’lI try to keep the cigarette till someone says put it out. Not smoking in elevators makes sense to me. You’re only in the elevator for three minutes.

JOHN: You’re such a militant smoker but I’ve seen you start screaming about smoke getting in your eyes and ears.

FRAN: I’m against other people smoking. I’m in favor of smoke in lungs, not in eyes.

JOHN: The one thing that’s against your image of being such a militant smoker is that you smoke such a low-tar brand. Don’t you think Luckies or Camels would be more fitting?

FRAN: Yes, well, that’s what I used to smoke. The last time I had a chest x-ray the doctor told me to stop smoking and I consider this to be stopping smoking. Smoking Carltons isn’t really smoking, it’s more like breathing deeply in a warm room.

JOHN: Do you smoke twice as much?

FRAN: I think four times as much.

JOHN: How has money changed your life?

FRAN: It’s made me richer.

JOHN: Describe a typical day in the life of rich Fran Lebowitz.

FRAN: I wake up in the afternoon in a nicer house filled with nicer furniture. The best thing is I get to wake up when I want to get up because I have phones that shut off and an answering service.

JOHN: When they answer.

FRAN: But this way I don’t have to call people back. Having an answering service that doesn’t answer gives me the perfect excuse to say that I don’t get people’s messages.

JOHN: Is there anybody you’re jealous of?

FRAN: Not at the moment since he’s in the hospital, but only the Pope. Jealous isn’t the right word, envious. Not for the getting shot part but for the job, I’m very envious of the Pope.

JOHN: In Social Studies there’s a lot of Catholic humor, why are you drawn to that subject since you were not raised Catholic?

FRAN: Because it’s so funny.

JOHN: God knows I know that. But I think it’s great to have a Jewish writer, they always write about Jewish things but you don’t, you write about Catholic things. Do you think they’re similar?

FRAN: No, I don’t at all.

JOHN: I do in a way. Guilt is fairly similar.

FRAN: But it’s a different kind of guilt. Jews don’t really have guilt about sex the way Catholic people do. Jews, they never mention sex so you don’t have to feel guilty about it. I think the reason I wrote about Catholicism is that it’s really a perfect subject for a humorist because it’s so strict. The reason there hasn’t been any great American comic novels for a long time, the way there are great English comic novels, is because there’s no class system here. Someone who is a humorist or a satirist really needs something to work against and the Catholic church is perfect for that. In order to make fun of something you have to have something concrete to make fun against. The Catholic church offers a perfect opportunity for any satirist who cares to tackle it.

JOHN: Have you read the new book, which I roared when I saw the cover, How the Pope Became Infallible?

FRAN: No. It’s a terrific title.

JOHN: In both your books you seem very paranoid about your address book, has anyone actually tried to steal it?

FRAN: I once woke up to find someone jotting numbers out of it.

JOHN: Since we share a mutual disrespect for animals, your chapter “Pointers for Pets,” I really liked and identified with, but did you ever have a pet as a child?

FRAN: First of all I had a younger sister. Second of all I had, when I was very little, like three or four, a parakeet that I starved by eating its food. I didn’t deliberately do it. I was too young to understand the correlation between eating and staying alive. My mother would give me celery tops and seeds to feed the bird which I would munch on my way down the stairs. And one day apparently my mother went down to find the bird dead in his cage and when I went down the next morning and found the cage empty; my mother told me that the bird had flown south for the winter and I believed her until about three or four years ago. And I had two or three cats which always mysteriously disappeared when I went to camp for the sum-mer.

JOHN: Ooh cats, they suck babies breaths when they’re sleeping it they’ve had milk. Do you believe that?

FRAN: No, I didn’t know that.

JOHN: What would you do if someone gave you a pet as a present?

FRAN: I would shoot them. Who would give me a pet as a present?

JOHN: An enemy.

FRAN: I think I’m as likely to get a plant. No one would ever give me a pet.

JOHN: Do you expect hate mail because of the chapter against pets?

FRAN: Not really because I put it in Interview.

JOHN: I mean from the book?

FRAN: I don’t, the reason being that I think that most people who are going to buy my book know….

JOHN: Your attitude.

FRAN: And they’re not going to be shocked by it. I’m not saying that I won’t get some hate mail.

JOHN: Have you gotten hate mail before?

FRAN: Yes, tons. Not very much from the book because people don’t go and spend ten dollars on a book until they pretty much know what it’s going to be about. I got a lot of hate mail at Mademoiselle. If ever there was a wrong person in the wrong place at the wrong time it was me at Mademoiselle. I have been told that the hate mail I got on my plant piece was the most they’d ever received at Mademoiselle. There’s a piece in Social Studies called “Tips for Teens” that I originally published in Newsweek and I got an avalanche of hate mail.

JOHN: Because you told teenagers to smoke probably.

FRAN: Most of the hate mail was from teenagers.

JOHN: Have you ever met a teenager you liked?

FRAN: You mean recently?

JOHN: Ever? Since you hit twenty.

FRAN: I don’t know what you mean by like. I think the thing about teenagers that’s unfortunate is that they’re so cute. On the whole I must say I’m not the biggest fan of teenagers. Teenagers are insufferable. I don’t even think other teenagers like teenagers. I had a plan that I unveiled on the briefly-lived David Letterman show on TV which was that I think all the teenagers should be moved to a less populous state like Nebraska or Wyoming. All the regular people can move out and all the teenagers in the country can live together in one state and annoy each other.

JOHN: Do you get fan mail?

FRAN: Yes.

JOHN: What’s a typical fan letter like?

FRAN: I have a wide range.

JOHN: They don’t send money? That’s the only kind I like.

FRAN: No, sometimes people send me things. Sometimes people send me food.

JOHN: Liz Rene, when she used to go to promote Desperate Living used to take deposit slips and so when people asked her for her autograph she would sign them and she thought, well maybe if they felt like it they could deposit something later. I thought that was a really good idea.

FRAN: That’s a great idea. Some people give me money to sign in bookstores. I’ve gotten cake and candy and stuff like that. And I must say Andy has been my mentor in saying, throw it away it could be poi-son, it could have drugs in it. The weird. est stuff that I ever got in the mail was someone was sending me, this was about two or three years ago right after the book came out, someone started sending me his teeth, real teeth. I would get about one tooth every two weeks. I got probably around ten teeth and then I stopped hearing from him.

JOHN: It’s better than dog shit, Fran, I used to get that and my distributor used to forward it to me. I know this is a touchy subject, but are you still having apartment problems?

FRAN: This is something so emotional that I can’t discuss it, John.

JOHN: If you found a great apartment in SoHo, even though your contempt for the neighborhood is quite well known, would you move there?

FRAN: At this point, if I could afford it. If I could figure out a way to get from out of my apartment into a taxicab without walking through SoHo.

JOHN: You have to wear one of those bags over your head like a criminal.

FRAN: I’m not worried about people see. ing me, John, I’m worried about seeing them.

JOHN: You should move to Baltimore then, I can get you a great co-op.

FRAN: I think it’s a little far for me.

JOHN: How do people in LA react to your rather negative opinions of their town when you’re there promoting the books?

FRAN: The thing is that when I write about LA I’m really writing about Beverly Hills. I’m not writing about the regular people of Los Angeles of whom I’ve met none. Most of the people I meet there are from New York and they all either apologize to you for being there or tell you that they’re really only there because they make 6 million dollars a year living there.

JOHN: Don’t you laugh a lot when you’re there? I’m always laughing when I’m there.

FRAN: Well, I laugh as much as possible, John. I already know what it’s like, it’s not funny to go anymore.

JOHN: Is there any job you’d like to have besides being a writer? Could you branch out in any other career?

FRAN: You mean besides being Pope? Except for Pope I really can’t think of any other job. Empress. I would like very much to rule. Any job that would involve ruling large numbers of people I would be interested in.

JOHN: What do you hope to be doing on your fiftieth birthday?

FRAN: I hope to be retired. Nothing. | hope to be doing nothing in a very large house.

JOHN: Well Fran, I think we should end it with what’s next?

FRAN: I’m going to be writing a novel which is to be called “Exterior Signs of Wealth” and that will be even smaller and more expensive than Social Studies.