camp

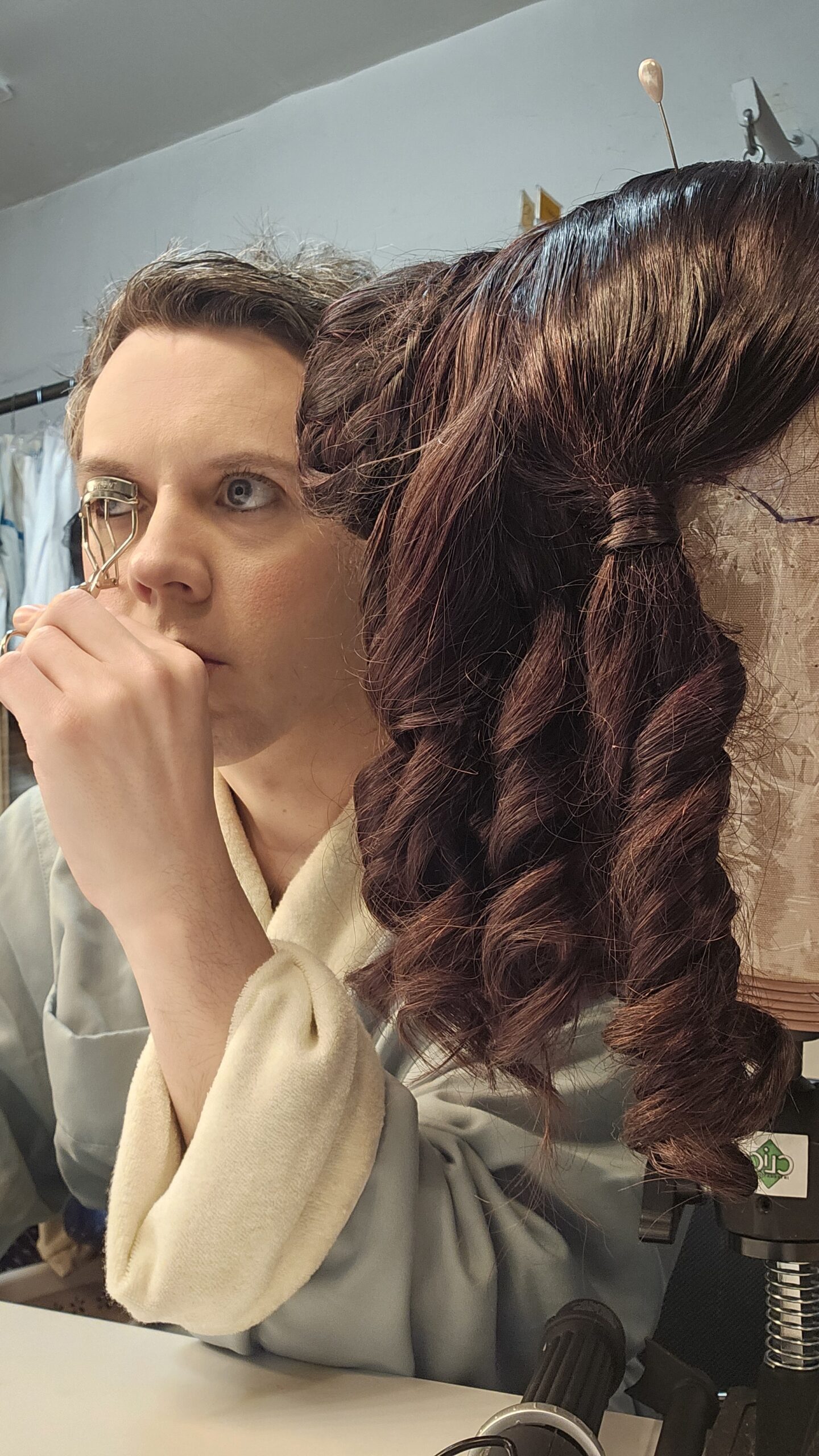

How Cole Escola Reimagined Mary Todd Lincoln as a Debauched Cabaret Star

A few weeks before the opening of Oh, Mary!, Cole Escola’s uproarious reimagining of the weeks leading up to Abrahram Lincoln’s assassination, the playwright and star is a little nervous. “I can’t wait for it to open so I can just do the show,” Escola told Charles Busch, who’s currently taking similar creative liberties with the wives of famous men in Ibsen’s Ghost at the George Street Playhouse. In Oh, Mary!, Escola’s rare comedic gifts are on full display in the role of Mary Todd Lincoln, who hides liquor around the White House as the president, in the thick of the Civil War, secretly gets blow jobs from twinky White House aides and tries to curb his wife’s alcohol consumption. She also dreams of being an actress, an ambition President Lincoln only indulges to keep her busy and out of his hair. The play, directed by Sam Pinkleton at the Lucille Lortel Theater downtown, is “rather disrespectful to the memory of both Mary and Abe, and hopefully equally disrespectful to both,” Escola says, but historical accuracy is entirely beside the point (just wait ’til you see the twist ending). While in previews, Escola hopped on Zoom with Busch, one of their personal heroes, to talk about revising while rehearsing, the sirens of Old Hollywood, and loitering outside Olivia de Havilland’s house in Paris.

———

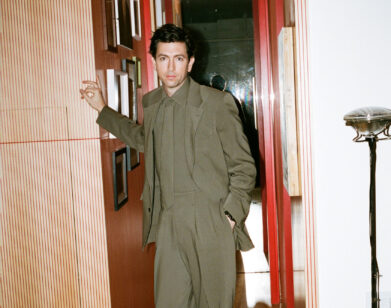

CHARLES BUSCH: So this is one of those interviews with the old Charles Busch and the young Charles Busch.

COLE ESCOLA: Ms. Channing, it’s such an honor. You’ve been on my mind a lot lately because I’m in previews and I’m thinking about specifically the part in your memoir where you’re talking about Vampire Lesbians of Sodom and the first time it was reviewed. I’ve never had anything of mine produced before, or reviewed, so this is miserable.

BUSCH: This is your first play?

ESCOLA: Yeah.

BUSCH: Isn’t that something? It’s all awfully exciting.

ESCOLA: It is.

BUSCH: And terrifying.

ESCOLA: Terrifying. I can’t wait for it to open so I can just do the show.

BUSCH: Play it, I know. I remember when Vampire Lesbians of Sodom transferred Off-Broadway. Of course, that was a strange thing because it was never meant to really be a play. It was just created as bar room entertainment. Then fate kept moving and we decided to move it for a commercial run. And the week before we opened, I panicked thinking, “Oh my god, this wasn’t meant to be scrutinized and reviewed and all that.” I’d always dreamed of being reviewed by the New York press.

ESCOLA: You said in your book that you spent a night trying to beef up things or make them deeper before you and your director realized this is the show that people loved and you needed to trust it.

BUSCH: I thought I had to try to make it literary, put a lot of big words in there. And Ken Elliot, the director and producer, wisely said, “This is the play that people seem to have enjoyed.” How long have you worked on this play?

ESCOLA: I had the idea in 2009. I liked the idea so much that I was scared to write it, you know what I mean? I wasn’t sure I could get it down as good as I had it in my mind. And then in 2020, during lockdown, I had nothing going on and I thought, “Well, get it out or die with it.”

BUSCH: Mary Todd Lincoln is just one of those people I’ve always been fascinated by.

ESCOLA: I love cultural tent-poles that people know about, but where there’s so many blanks you can fill in. I like making stuff up about her, but I also love the real stories about her. Her spending sprees, her acting out at parties, people sending Abraham notes saying, “Your wife is behaving terribly, please come get her.”

BUSCH: When does the play take place?

ESCOLA: It takes place in the weeks leading up to Abraham’s assassination and up through his assassination. But I make up the series of events.

BUSCH: It’s interesting that both of our plays are rather similar in a sense. My play is about the wife of Henrik Ibsen, the Norwegian playwright. And just to cover my ass, I’ve subtitled it “an irresponsible biographical fantasy.” That clears me on anything, because really I’m not a research kind of person. I read this one 850-page book. I loved Ibsen’s plays, but I didn’t know anything about him. I read this one enormous tome and was sort of taken with the idea of his wife, who was just the dutiful partner to the great man. But there was very little about her interior life or her opinions or her emotional issues, so I just made it all up.

ESCOLA: I can see why that would spark you. I think of Norma Shearer a lot when I think of some of your characters. There’s something so funny about a “good” woman, the way you play that character.

BUSCH: I’ve done a couple of parts where I’m a disreputable dame, but I enjoy finding the comedy in the good woman, the good wife.

ESCOLA: My play is rather disrespectful, I would say, to the memory of both Mary and Abe, and hopefully equally disrespectful to both. I’ve actually been thinking about you in this whole process, because I find it hard to rehearse. I find it hard to be an actor when I’m sort of listening for the writing.

BUSCH: Oh, really?

ESCOLA: When I’m in the middle of a scene I’ll be thinking, “That sentence would flow better if those two words were swapped.” Just things like that.

BUSCH: You’re in previews now?

ESCOLA: Yes.

BUSCH: It’s a little frustrating, I have to say. It’s weird having one more week to go and thinking, “Oh, I wish I could just put these changes in right now.” I wouldn’t want to screw around.

ESCOLA: These damn unions. I’m kidding.

BUSCH: [Laughs]. It’s interesting to talk to you about this. You’re at the beginning of this journey. I’ve been doing it for so long. Sometimes, over the years, some new theaters that I’ve worked at have said, “Well, do you think it would be helpful to you for the first read through to have somebody else read your part?” I said, “No. Are you kidding? I’ve written this part for myself and it’s constructed around me.” In those cases I sat there terribly frustrated. It’s like being at a shooting gallery and, as each line is killed, it’s like “Bam, killed that laugh, bam, killed that laugh,” and I’m being judged by this. Although I do believe that my ego is more vulnerable while being an actor. I was thinking about this the other day. I thought, “I would accept it more easily if a critic said, ‘Charles Busch was brilliant in his play that needs a lot of work’” than if it was, “Oh, the play is brilliant, but it would be better if Charles hadn’t played the role.” That would destroy me.

ESCOLA: I think that would destroy me, too. I am way more sensitive as a performer, almost to the point where I’d rather not perform. Someone came up to me after our third or fourth preview last night, and said, “Oh, I didn’t realize you’re still in previews. I’d love to come back when Mary really grows.” And I thought, “Oh, she was apologizing for coming to a preview because she felt she should have come later.” But then I thought, “So it isn’t grown enough for you?” Yeah, that kept me up…

BUSCH: What I find lately is the number of people who have come to see it, people that I know, and they email me and say, “Oh, I loved it. Just marvelous, and the cast is just great.” And then they don’t say a word about my performance. I think it’s so rude! Immediately, I think, “Oh, they don’t like what I did.” Or is it that somehow, since you’re the playwright, they assume the whole totality is you.

ESCOLA: For my ego’s sake, I have to believe that. They’re probably like, “I loved what you made.”

BUSCH: It’s so vulnerable, it’s so terrifying. And it gets worse rather than better. But if I’m still here in 30 years, I’d like to hear what you have to say on that matter.

ESCOLA: I certainly don’t have the “fuck you” energy I did when I was 20. I’m only 37 now, and I do feel more vulnerable.

BUSCH: I’m 69 years old, honey, and I don’t have trouble with memorizing lines. But there’s always this knowing anxiety that, somehow, I’m going to forget a line. And it’s not that big a deal. I really do think that if I didn’t have to memorize it, it would be fine. When I do stage readings and I’m as cool as Ethel Merman, I could go in front of Yankee Stadium, not a nerve. But when there’s an element of memorization there, that’s enough to get me so anxious and go over the lines, over and over and over, until you end up jinxing yourself.

ESCOLA: It’s funny you say that because I realized yesterday, when I put a new line in the show yesterday, right in the middle of it, and I was like, “Okay, I need to burn this into my brain before the show starts.” Then it was getting me so worked up and I realized, “Wait, I wrote it, whatever. It’s from my brain.” Even if I don’t say it word-perfect, whatever I say is going to be right enough.

BUSCH: I’m curious about something. Now, I know Sam Pinkleton, your director.

ESCOLA: Oh, you do?

BUSCH: I haven’t seen him in many years. He was assisting a director that I was working with and it was clear that Sam was going to go places. Have you worked with him before?

ESCOLA: He choreographed a play that I did at Dixon Place 12 years ago. When I met with him to talk about Oh, Mary!, it was just immediate. The Ann Miller references, everything just clicked.

BUSCH: Did Sam gave you notes?

ESCOLA: Yeah, and still does. He’s great. Do you know Bianca Lee?

BUSCH: Yes. I adore Bianca.

ESCOLA: She’s in the show as well. She loves you and speaks very highly of you.

BUSCH: She’s wonderful. I’m so looking forward to seeing her with you.

ESCOLA: I just have to praise your book again. I want it on record how special your memoir is. The way you make the people from your life seem like these grand Hollywood stars, and then the way you make these grand Hollywood stars seem like real people, really blew me away.

BUSCH: When you told me that, I thought, “Wow, that’s exactly what I hoped someone would say.” A major part of the book was going to be about my aunt Lillian and other people from my years of Theater in Limbo. I was counting on them being interesting enough to be central characters.

ESCOLA: I really fell in love with her in a big way.

BUSCH: My aunt was the most important figure in my life in many ways. She was human. There were a couple of times I was a bit disappointed by her reactions or whatever, but she was human.

ESCOLA: But she never saw you perform? The fact that she never saw your plays really was–

BUSCH: Shocking?

ESCOLA: That stung a little bit, I’m sure. I mean, my mother isn’t coming out to see Oh, Mary!

BUSCH: Why is that?

ESCOLA: I don’t know.

BUSCH: Where does she live?

ESCOLA: She’s in rural Oregon, which is far, but she’s never been to New York City. I don’t think she’s been on a plane since the ’70s.

BUSCH: Oh my gosh.

ESCOLA: I think it would just be too overwhelming for her to be here. But there is a part of me that’s like, “Really?”

BUSCH: Have you discussed it with her? What does she say?

ESCOLA: She understands how important this is for me, and she’s really, really proud of me. But I just think the thought of coming to New York just terrifies her, or the thought of even going to the airport.

BUSCH: She’s an interesting lady. Can you explain a little bit more about who she is?

ESCOLA: You know how in gangster movies, the mothers are portrayed as suffering, fragile, brittle women?

BUSCH: “Ma.” Yeah.

ESCOLA: Maybe there’s a bit of agoraphobia happening.

BUSCH: Is your father alive?

ESCOLA: No, he passed away 14 years ago, but we were never close.

BUSCH: You were raised by your mother.

ESCOLA: By my mother, by my grandmother, who was the one who showed me old movies. I think you talked about this in your book, but who is the first actress that you sort of glommed on to?

BUSCH: I loved watching classic film on TV from the earliest age. I bonded very easily to Bette Davis and Norma Shearer.

ESCOLA: I love the Bette Davis stories in your book about the other actresses all being like, “She was ugly.”

BUSCH: When I met Claudette Colbert and then later Claire Trevor, they both were saying, “Well, of course Bette Davis was the first ugly star.” They didn’t say it in a nasty way. It was just, “Well, of course.”

ESCOLA: That was the first big laugh for me in the book.

BUSCH: I was fortunate that I came around when a couple of those ladies were still alive. If I’d been there 10 years before, I really would’ve gotten to know Joan Crawford.

ESCOLA: I just remembered the [Greta] Garbo story from your book, which is so special. A few years ago, before she died, I went to Paris and I went to Olivia de Havilland’s house. I think she was 102. I just sort of circled the block because I was like, “She must be home, she’s 102. Where could she be?” I was just trying to pull in as much energy as I could.

BUSCH: About a year ago, Garbo’s apartment was once again on the market. And I saw on Facebook that a friend of mine, an author who writes about classic film, knew the realtor and he’d spent some time in Garbo’s apartment. I immediately messaged him and said, “How can I get in there?” He arranged for me to call the very kind realtor. So I went over there and her apartment was still pretty much intact. After she died in 1990, she had willed the apartment to her niece and they kept it in the family and didn’t do anything to it, just kept it as it was. And then they finally sold it in 2017 to a very wealthy couple who kept the basic moldings and even a rug. They were Garbo fans. So I went over there. I felt like in the movie Queen Christina, when Garbo is in the tavern room and she’s touching all the objects so she could remember exactly what it was like. It was so weird looking out at these extraordinary views of the East River from Garbo’s window and thinking she stood in that very spot looking out that window at that exact same scene.

ESCOLA: Did you swipe anything?

BUSCH: [Laughs] No.

ESCOLA: You didn’t chip some paint off the wall?

BUSCH: No, I just have my memories.

ESCOLA: Did you think in a Swedish accent while you were walking around?

BUSCH: Yes. I only thought in Swedish the entire time. Actually, in this new play, I’ve got to speak Norwegian.

ESCOLA: Oh, really?

BUSCH: Yeah.

ESCOLA: Do you have an accent in the play?

BUSCH: No, not at all.

ESCOLA: I like to think that somehow you have a perfect Norwegian accent without even trying.

BUSCH: It’s very hard, because it’s one of the languages where half the letters are silent. It has long, long words. In all of my plays, I give actors, either myself or someone else, these set pieces that could almost be taken out of the play, but it’s a little minor tour de force. That’s my gift to me.

ESCOLA: Do you write parts of your plays for you to get water backstage?

BUSCH: Well, I don’t know about that. But actually, in this play, I didn’t want it to be quite as exhausting as some of my other plays. I once changed clothes six times in the first act alone. My last play, The Confession of Lily Dare, took place over about 30 years.

ESCOLA: I loved that show so, so much.

BUSCH: It was one of my favorite things I’ve ever done.

ESCOLA: I hope you do it again.

BUSCH: I doubt it. I don’t think I could work that hard.

ESCOLA: I only have one costume change in this.

BUSCH: Really?

ESCOLA: I think you’re going to have some notes for me after you see it. “You didn’t give yourself the star entrance. You don’t have enough costumes. What the hell are you doing up there?” I’m exhausted afterwards and I’m realizing, “Oh, I wish I would’ve had one scene where I’m just off-stage just drinking some water.”

BUSCH: Are you on the entire play?

ESCOLA: Not the entire play, but basically when I’m off-stage, I’m putting something down to pick something up.

BUSCH: Oh, my gosh. Those days are long gone for me. I come on in each of these scenes, I’m on the very top of the show. But then, during the other scenes, there’s maybe eight pages where I’m changing clothes and I have time to breathe. But once I come on, I’m on until the next blackout. I feel like a hooker, actually. I get on and then this first person comes on and fucks me—metaphorically, of course. And then they leave and the next person comes on and fucks me. And then they leave and the next one one comes on and fucks me. And then, finally, blackout.

ESCOLA: I have a question. Do you like acting on camera?

BUSCH: I love it.

ESCOLA: Oh, yeah?

BUSCH: Yeah, it’s so interesting to try to do that minimalist movie acting. It’s an interesting challenge when you’re playing a flamboyant character.

ESCOLA: I’m too big for the screen.

BUSCH: The characters I see you do on television are sometimes rather minimalist, in a way.

ESCOLA: I also don’t enjoy the act of acting on film. It’s so piecemeal. I always have the thought of, “This is it. You get one take, maybe three if you’re lucky. And then that’s it and it’s in the editor’s hands.” Whereas live, I can sort of say, “That was the best performance I’ve ever given and it’s just a shame nobody will ever see what I did last night.”

BUSCH: I like them both. I hope we get to make that movie together. But if I stop doing plays, there are other things to do.

ESCOLA: Cooking.

BUSCH: Cooking, yes. But I have an idea for another book that I’d like to write.

ESCOLA: Fiction?

BUSCH: Yeah, I’ve always wanted to write just a paperback murder mystery. I read them and I would just love to write one. But I’m not sure I have the kind of brain to plot so meticulously like that.

ESCOLA: I bet you do.

BUSCH: Well, this has been really delightful. I just adore you, Cole. I knew you were the real deal the first moment I laid eyes on you. I just think it’s so great that you’ve written a play, even if the critics review my play and say, “Well, we have Cole Escola doing Oh, Mary! and that’s the way it’s done.”

ESCOLA: My fear is the opposite. My fear is like, “If you want to see Charles Busch, you can go uptown. You don’t need to see this wannabe upstart.” But I guess I’ll see you at the Obies and we’ll duke it out there.