IN CONVERSATION

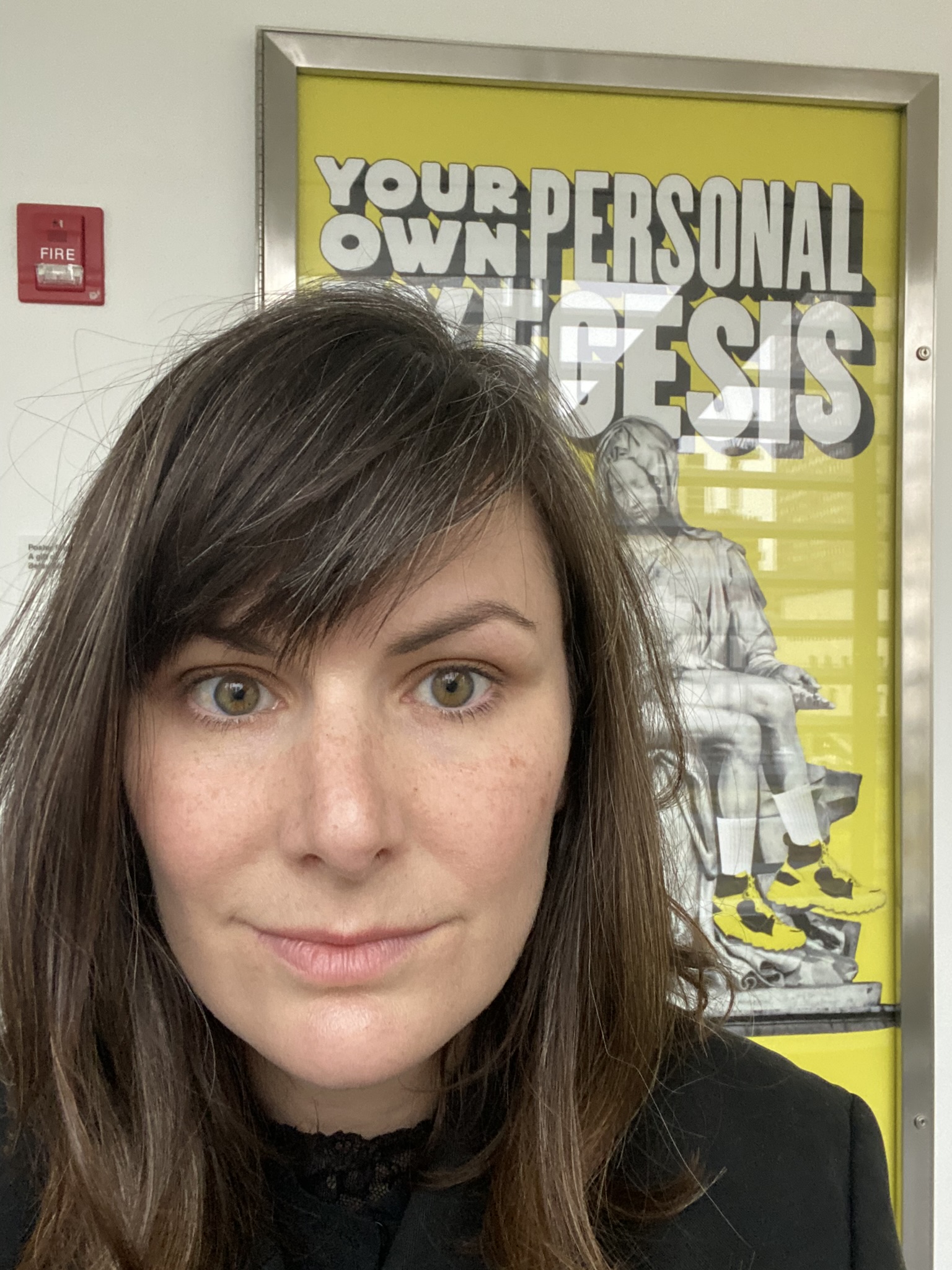

Chloé Cooper Jones Asks Julia May Jonas About Her Breakout Year

The novelist and playwright Julia May Jonas has had quite a year, to put it mildly. First, Jonas published Vladimir, a provocative and utterly contemporary campus novel which, for a period last spring, was ubiquitous on the subways. Knowingly evocative of the author of that most famous novel of perversity and exploitation, Vladimir is narrated by the literature professor at an unnamed college, who we meet as her philandering husband John, a professor at the same school, stands accused of carrying on relationships with dozens of former students. Jonas’s narrator is not so innocent herself, and the arrival on campus of a handsome assistant professor named Vladimir provokes own exercise in vengeance and objectification. In some ways, she resembles Kat, the reverend and youth group leader of Your Own Personal Exegesis, Jonas’s new play at the Lincoln Center Theater. Concerned, like Vladimir, with the feminine id as it runs afoul of sexual politics, Exegesis is strange, incendiary, and often laugh-out-loud funny, featuring an intermittent call-and-response church service with the audience and a bizarro third-act staging of Reverend Kat’s version of the Passion Play. It’s no wonder that Jonas, a professor of theater at Skidmore College, cites Aristotle and Ingmar Bergman as influences. In conversation with the author, journalist, and good friend Chloé Cooper Jones, whose memoir Easy Beauty came out in April 2022, the two writers discussed Brechtian theater, subverting the canon of great American plays, and all the hard work that preceded Jonas’s breakout year.

———

CHLOÉ COOPER JONES: Hi, Julia!

JULIA MAY JONAS: Hi! I didn’t know you had a dog.

JONES: Yeah, this is Dolly. She needs to be involved in everything I do.

JONAS: Oh, good.

JONES: I grew up on a farm with farm dogs, which were very different. I never wanted a dog. But then one day Wolfgang [Jones’s son] turned to me and he was like, “Look, a boy needs a dog.” I can’t argue it. I was like, “Yeah, maybe?” So we got this dog.

JONAS: Yeah. Well, he has an uncanny way of phrasing things.

JONES: He sure does. He went to your play yesterday and he loved it.

JONAS: Oh, great.

JONES: He had a lot of questions. Actually, he would have been a good person to do this interview with you. When we left, he was like, “Where is she? Where’s Julia?” Like, he wanted to immediately engage with you.

JONAS: Next time. I actually went to the evening show and my parents brought like, 10 of their friends.

JONES: Oh my god. I should have come to the evening show and heard all the questions from your parents’ friends. One thing I was really thinking a lot about after seeing the play again yesterday is what tools are at the disposal of any creative medium. And how is the creator or the artist using all those tools? Playwriting and film and TV is so daunting because it just feels like there are so many tools, right? Seeing your play again, I noticed all these really small things that I hadn’t noticed the first time around. And I was thinking about what I think makes you uniquely special as an artist, what I love so much about your work, and one of them is that you use your audience as a tool at the disposal of your medium in both Vladimir and Your Own Personal Exegesis. So that’s where I wanted to start, talking to you about the tools at your disposal in both of these mediums and why it feels so important to make sure that the audience is not forgotten. Does that make sense?

JONAS: Yeah, it really makes sense. When I would write my syllabus for my advanced playwriting class, I would talk about the idea of a play being both a map, but also a ride. So you want to put your audience at the beginning of a ride, because you have to acknowledge the fact that you’re inside of a durational form. I want to use all the access points that I can get with an audience. And I also want the audience to kind of never forget that they are an audience. For me, that’s very essential in any work that I’m engaging with. I’m kind of meandering, but—

JONES: My dream is that I’ve asked you a question that’s hard to answer. Then we actually have something interesting and new to offer the readers of Interview Magazine. You and I both have been on book tours and have been asked the same questions a million times…

JONAS: Okay, good, good. Because I do feel like this is a different way of looking at it, through the lens of complicity, and thinking about what complicity means inside of a theater and what complicity means when you’re reading a book. In my late 20s, I got very involved in a Buddhist community and did a lot of meditation and a lot of Buddhist study. This kind of went alongside all of my literary journeys that I had been on, so I think they’ve affected each other in a way. One of the things that was so potent for me that I took from Buddhism was this idea that our experience of life is like watching a movie. I’m saying this to someone who has a PhD in philosophy, so this is a little embarrassing…

JONES: No, don’t worry about that.

JONAS: When you take a moment and look at consciousness, it’s that sense of turning around in a movie theater and going from being sucked in to recognizing the frame of everything around it. I’ve always found that really, really fascinating, because that feels so related to my experience. I feel so consistently skeptical of my thoughts, my beliefs. I think some people believe what they believe. And I have always had a very skeptical relationship to my thoughts and my beliefs and my feelings and my emotions, for better, and I think for worse. So from inside both a play and a novel, it’s a way of examining the mechanism and pulling us outside of the trance that we all get into, which is believing our thoughts, believing that our experience is true. With Vladimir, for example, you start inside of this woman’s body. She’s never named, and she’s kind of shocking and also very attractive and charismatic. Then she starts to act in this way that feels like, “Oh my gosh, I would not expect her to act this way.” To me, that was very purposeful. I’ve just always been interested in disrupting the audience.

JONES: Yeah.

JONAS: Similarly, in Your Own Personal Exegesis, I want the audience to feel like they’re participating. And I want to disrupt them from traps that we can fall into, be they sentimentality or judgment, or any sort of clear assumptions about morality or people. I think a form can disrupt that and make us see it better than anything. The best explanation of Brechtian theater, I think, is in [Bertolt] Brecht’s essay “The Street Scene.” And he says, you can watch a car crash happening in real time and have no thoughts about it. You’re only swept up inside of the emotion, there’s no way that you can see why or how it happened. But if someone tells you about a car crash, and you’re one step removed from it, then you can start to intellectually engage with it. So for me, inside of theater, if you can use the form to prevent people from being swept up inside of the content, then it’s activating, or it’s activating for me. I don’t know if it’s the WASP in me or the Midwestern, but I’m much more affected and stimulated when I’m given a sense of remove from something.

JONES: Well, there’s so much I want to say about all of that. I love this. As you were talking, I was thinking about where our work is similar. A really big part of the form in Easy Beauty is perceptual shifting, this kind of relentless perceptual shifting.

JONAS: Yeah.

JONES: So you’re talking about form, and the sort of necessary remove that form can offer so that you can intellectually engage with things. One thing that I found so striking about both of these works of art that have come out this year for you is that both of these works have some pretty sticky moral questions at their center and you managed to find such incredible contextual balance. In Vladimir, page to page, I would feel differently. And by differently, I actually mean more complexly, right? It’s not being jerked in every direction, but actually doing deeper and deeper into the problem, not to find clarity, but to find complexity. In order to do that, you have to have deep empathy for every single person you’re putting on the page or on the stage, right? You have to see things from their perspectives, and their darkest moments need to be tied to a deep understanding of their humanity. So will you talk about the relationship between form, content, and building out a character?

JONAS: I mean, what a great question.I feel like I could talk about this in the context of both of our work, because that’s what makes “Easy Beauty” so satisfying to read. You’re not letting yourself off the hook. Which seems facile to say, but you’re constantly digging deeper for these stickier and tricker emotions and desires. And that’s because you’re writing about a human being. That, on the one hand, is what’s so strangely radical about it, you know? And it sounds a little flippant, but I’m interested in truth. Like, Ingmar Bergman is not very fashionable right now, but when I first watched him when I was in college, I just remember encountering characters and thinking, “Oh gosh, I’ve never seen someone portrayed someone and put them on film in a way that made me feel like I was seeing a whole person that did, in fact, contain multitudes, like all of us.

JONES: I think Bergman’s in fashion, right?

JONAS: I don’t know, I feel like some people think he’s overwrought these days.

JONES: Well there was that major adaptation of Scenes From a Marriage.

JONAS: I guess so. I feel like he’s not in fashion with film people anymore.

JONES: Maybe, yeah. I don’t know. I like him!

JONAS: Oh gosh, I love him!

JONES: Yeah! Sorry, go ahead.

JONAS: I remember that being really revelatory to me. Like, I am going to be interested in trying to get to the puzzle of truthfulness in character because that’s just where my interest lies. And ‘m working on things now and I just can’t even talk about them because I haven’t found it yet. I can’t make it until I know how the form is going to interact with that and what the real question is going to be. Until I have those three things in relationship to each other and I’ve worked them out in my brain, I don’t feel like I can work on something.

JONES: I love that. Maybe that’s a good place to ask you some process questions that I’m really fascinated by or want to know about how you work. So the three things that you sort of start a project with are character, form and—

JONAS: The driving question.

JONES: Do you feel like the question always comes to you first? I feel similarly that there’s always question, there’s always form. But a lot of times, the very first thing that comes to me is setting, and setting gives rise to a question.

JONAS: It’s interesting, because sometimes the question comes to you through the writing of something and sometimes it doesn’t. With Vladimir, the question that I started with was how do we account for our desire, how do we talk about desire? And then I had an image, which was in the rubble holding her husband’s heart in her hands. And I thought, “Okay, well, that’s not what it’s going to be, but I’m going to move toward something that feels like that.”

JONES: Oh, I love that. I love the idea of having an image that’s sort of buried, that you’re working toward, and maybe not literally. That’s so good.

JONAS: And then the form starts to kind of creep in, right? That’s such a gothic image, this idea of getting further and further into the woods, traveling into these places of darkness. So then I started thinking about all of these gothic novels and how they could start to inform what the journey of that novel would be. And then for Your Own Personal Exegesis, I wrote the scene between Addie and Beatrice, where they’re talking about the Venn diagram.

JONES: Yeah.

JONAS: Addie is saying, there’s vertical lines on one side, there’s horizontal lines on the other side, and the place where they come together, that’s how Jesus can be fully man and fully god. And Beatrice is trying to wrap her mind around that. That was actually an image that was given to me when I was a kid. I could never wrap my mind around that. I just felt like. “This doesn’t make any sense to me.” And part of what that whole idea was is this idea that that’s why we should feel so sad and grateful for God giving up his son. So I wrote that scene with them, and then I thought, “Okay, yes. This is about people’s relationship to their flesh and spirit.” And it’s going to be inside of a church service. The church service, in a way, is its own memory. Week after week, it’s a memory, a commemoration, a reminder to tell the story so that people can make good choices in the upcoming week, which I actually think is very helpful for a lot of people. So I feel like that’s where that kind of emerged from.

JONES: If you had said, “Guess which scene the place originated with?”—as a writer, I would have guessed that scene, because it just feels like where the soul of the question is throbbing the loudest. There’s another scene, too, where Beatrice is wondering why the crucifixion is so sad. And one of the most painful and affecting lines of the whole play is Beatrice saying, “Isn’t God the one person we don’t have to have empathy for?” Beatrice, more than anybody in the play, is really searching deeply to understand everybody and understand herself and why she doesn’t feel as seen or as special or as desired or as chosen as other people. So when she says, “Isn’t there just one person I don’t have to empathize with? It’s God, right?” Beatrice is the one that makes decisions with real stakes in the play. So, is she doing what you want your audience to do, that searching?

JONAS: I think that’s a great way of putting it. If I’m asking the audience to do anything, what I would be asking them to do is to get inside of somebody’s struggle in a real way. I just feel like we’re not being truthful with ourselves unless we can understand the kind of conflicting, contradictory, hopeful, reaching, good, bad, petty, magnanimous, strong and not strong forces that are all working inside of us. In both Vladimir and Your Own Personal Exegesis, I have people act in ways that are pretty morally reprehensible or questionable. So it’s not about advocating—you know what, Chloe?

JONES: What, Julia?

JONAS: In both works, I think I was really, really influenced by Aristotle, I mean, isn’t that so boring?

JONES: Not to me! I love Aristotle.

JONAS: “Hamartia” being this tendency that, if unchecked, can lead to our own demise, which is what is happening to the narrator in Vladimir, and it’s also what’s happening to Kat in Your Own Personal Exegesis. I was really thinking about how to play with these tendencies that all of us have, because that’s how a tragedy becomes a tragedy—not because a person is horrific, but because they have a tendency inside of them that leads to their own destruction and the destruction of others, sometimes. I have taught Poetics for many years, and my relationship becomes deeper and deeper every time I teach it. In Poetics, he has a direct statement about what the kind of character a person has to have in order to be a real tragedy and it can’t be someone you look down on, and it can’t be someone who is so great that we’re just watching them fall. It has to be a good person with this fatal flaw.

JONES: And often, of course, that fatal flaw is one that, if circumstances were different, maybe could be exorcized in a healthy way. But because of context and circumstances, this very deeply human and deeply recognizable flaw is turned into tragedy. And so I think that’s totally operational. That makes perfect sense to me. And it’s really beautiful, the execution of that in both these two works. Okay, I have another writerly process question that I’m really curious about. I heard you talk in another context about knowing when the story that you’re working on isn’t working, knowing when to put the play on the shelf, or in the drawer, rather. I think that type of discernment is the mark of a really great working artist. It’s not just about all the good things that become things, but all the work you do that doesn’t become something. So, how do you know when something isn’t working?

JONAS: When I feel like when something isn’t working, there’s a lack of cohesion to the choices I’m making. Like, I can tell that I’m starting to make choices because I’m having ideas like, “This could go here, or maybe this could happen, or maybe this could happen, or maybe this could happen.” I don’t know exactly how to describe it, but there’s a certain desperation I can feel in those types of moments. And that’s when I know that I need to pull back. I think that you have to constantly be willing to admit that something is not working. And then there’s the other kind of brilliant part, which is when you have finally tangled all the threads that need to be tangled and there’s a momentum that comes on. And you get to a point where you know you’re going to finish it.

JONES: One thing I always think about is how one of the most important tools for working artists is knowing how to make friends with failure. You didn’t just sit down at a computer for the first time in 2021 and then have a miraculous 2022. This is the result of a lot of work. And it’s just the beginning of what will be a very, very long career. But I wonder, that beginning tail of work that maybe a lot of people haven’t seen, what do you think that’s given you to put you in the place that you’re in now? Which is, I think, arguably having one of the best years of any artist in any discipline right now? That’s my opinion.

JONAS: That’s so daunting, Chloé, but I love it.

JONES: I mean, why now? What was the work that you needed to wrestle with in order to get to the point that you’re at right now?

JONAS: Yeah, I mean, I’ve done a lot of writing and certainly thinking about theater, and I have produced theater in smaller venues. I rewrote five classic American plays so that I could understand what they were doing.

JONES: Oh wait, that’s amazing! Wait, will you tell us everything about that?

JONAS: These are “male experience” plays. And I was like, “Okay, what’s other people’s experience?” Less so now, but when I began, American theater was so dominated by questions of masculinity, which I also find fascinating. What’s more fascinating than masculinity? I’m just as obsessed with it as everyone else. And for some reason, it feels endless. So I wanted to say, “Okay, how do I take these male experience plays and write them for the female experience?”

JONES: Can you tell us which plays you rewrote?

JONAS: Oh, yeah. So I rewrote American Buffalo by David Mamet, All My Sons by Arthur Miller, Long Day’s Journey into Night by [Eugene] O’Neill, True West by Sam Shepard, “[The] Zoo Story” by Edward Albee.

JONES: That’s a brilliant structure exercise, I feel like.

JONAS: Yeah, that was very teaching. I mean, I’m just always trying to be inside a state of becoming, as good old Bob Dylan says. And to always think, “Okay, how can I challenge myself next?” Other than a certain form of maturity that I’ve gotten through being a parent and being a teacher, I also think life just contributes to your artistic path. There’s not really a reason, necessarily, that this is the year that I’m having so much success, other than just a confluence of events and luck—

JONES: And work. The work.

JONAS: And putting in the work, yes.

JONES: It’s lovely to hear a concrete example of what putting in the work really looks like. And that’s a lot of studying and thinking and—

JONAS: Yeah, I think you’ve got to be interested in it, you know? You have to be interested in your thing. It’s not about applause. It’s about trying to make something, get better, think about how to work so that the work can reach people.

JONES: Totally. That’s it, thinking about how to work. Well, I know that our friendship is born of me being very interested in all your things. I feel so grateful for all the things you’re making and all the times I get to spend with you.

JONAS: Totally. Here’s to us. Thank you, Chloé.