BASS

“You Changed My Life”: Tina Weymouth, in Conversation with Este Haim

The email asking me to interview Tina Weymouth stopped making sense after, “Hi Este.” Tina, to me, has always been a woman on a screen and an idol. She’s the living embodiment of rock and roll, as evidenced in the 40th anniversary restoration of Stop Making Sense, which was released a few weeks ago. Needless to say, I was nervous. My brain was relentlessly screaming “Never meet your idols, Este” 24 hours before this interview. Thankfully, all of my anxious notions were quickly assuaged the second I got on the call. Tina and I found plenty of common ground in touring and songwriting and she even ended with some common courtesy—Tina’s wishes came true; I didn’t get bedbugs in Paris. Americans who can speak French fluently always make me feel bad. When I learned that she wrote the French lyrics for “Psycho Killer,” I shouted “Donne moi une forchette.” Tina makes playing the bass look like the most fun ever, which is why I was drawn to it in the first place. She’s the reason I give myself permission to really put my whole body into my playing. I had never seen a female bass player until seeing Tina on the small screen when I was eight years old. And now, 30 years later, she jumped through the screen once again and, in turn, has made me dream even bigger than before.—ESTE HAIM

———

ESTE HAIM: Hi. Oh, man. I am speechless right now.

TINA WEYMOUTH: Just have a little glass of champagne and you’ll be fine.

HAIM: Oh, I’m planning on getting wasted on the streets of Paris after this interview.

WEYMOUTH: Uh-huh. Okay, good.

HAIM: I’ve also been listening to Psycho Killer all morning, seeing if I can actually understand what David Byrne is saying in his French part.

WEYMOUTH: He got a lot of coaching.

HAIM: Do you speak fluent French?

WEYMOUTH: En peu, en peu. Ma mère est française.

HAIM: Oui? Wow. Voila. I can sort of understand it.

WEYMOUTH: Yes, you can. Because it’s Latin-based.

HAIM: Yes. I think my goal is to become fluent in French by 40.

WEYMOUTH: Oh, yeah. Kirk Douglas became fluent in French because he played Vincent van Gogh in some biopic. And also, Jane Fonda was married to Roger Vadim and she became fluent in French. Jodie Foster went to school there, and she’s fluent in French. Oh gosh, there’s so many Americans who are really good at it, much more fluent than I am. I think actors have a really good ear for accents and language.

HAIM: Well, I think musicians do. Right?

WEYMOUTH: You know what? Some more than others. Some are more rhythm-oriented, and others are more melody-oriented, and some are not musical at all, they’re just mathematical.

HAIM: Well, I think that you’re both, and I think that’s why you’re so inspiring.

WEYMOUTH: Well, I had a really amazing husband. He was instrumental, literally.

HAIM: Pun intended.

WEYMOUTH: Yeah.

HAIM: On my end of things, my father is a drummer.

WEYMOUTH: Oh, your father! He got you into playing bass. Did he select that instrument for you?

HAIM: Yes. You were also very instrumental in all of that.

WEYMOUTH: Oh, thank you.

HAIM: And my mother is a guitar player. They fell in love because they both had a love of music. At their wedding, instead of having a first dance, they had a first song, and my mom sang and played guitar and my dad played drums. When Danielle and I were kids, my mom taught us how to play guitar. Danielle, as a five-year-old, completely surpassed me, I wasn’t really allowed to watch MTV, so I didn’t really know what that looked like, a girl playing bass. I’d seen Joni Mitchell play guitar. I was like, “Okay, yeah, girls can play guitar.” But then my dad was like, “Ha ha ha, let me show you something.” He took me to the video store and he got Stop Making Sense on VHS. I was transfixed the entire time. The film itself is magical, but I think the most magical part is your part in it. I was completely enamored with you and how much fun you were having. I was like, “Oh my god, this girl’s having such a good time on stage. She’s dancing and she’s singing, and she’s really getting into it.” So I was like, “That’s what I want to do. That looks like fun.”

WEYMOUTH: That’s fantastic. And your band is fantastic.

HAIM: Oh my god. Thank you so much.

WEYMOUTH: The first time I knew about you was when you appeared on the Grammys. I think you were the third act, or something. We were watching, Chris [Frantz] and I, and we hadn’t watched the Grammys in years because they got so boring.

HAIM: Yeah, they can be boring.

WEYMOUTH: But we were watching that year and we said, “Oh, the Grammys have so improved.”

HAIM: Really? Oh my god. That is high praise.

WEYMOUTH: That’s what we said. We were really blown away until the pole dancers came on, and then we turned it off.

HAIM: You’re like, “I’ve had enough.”

WEYMOUTH: It was like the music went away. It was just no more music, no more melody, nothing. But we really enjoyed those first four or five [acts], up through Billie Eilish.

HAIM: Well, that Grammys was kooky, because it was also in the middle of the pandemic. The cool thing though was that we had Paul Thomas Anderson directing that performance.

WEYMOUTH: Oh, yeah. He’s pretty cool. And you were shown to your advantage because, instead of putting you on a proscenium stage, they had you right there, right there in the middle. It was wonderful. The camera panned around the three of you and we loved what you were wearing and how you sounded.

HAIM: Oh, man. This will be a core memory of mine for the rest of my life. There’s something so interesting about performing in front of an audience when you’re going to be filmed. I think I’m more conscious of it. I was going to ask you if, when you were filming those three shows at the Pantages [Theater], was there a feeling of, “Oh, I have to be on”? Or was it just always just like, “I’m on no matter what.” Because when I’m conscious of the way that I look, my playing sucks.

WEYMOUTH: Yeah, it’s a real harassment of women that we have to be conscious of how we look. That’s the first thing people say. It’s like you can’t get away from it.

HAIM: You’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t.

WEYMOUTH: It is crazy. You’d think in this day and age that we’d come to realize that women, if you take off their clothes, they’re all like beautiful plants. Some are very thick and short, and then some are very tall and sinewy, and that’s just beautiful. You go into a forest and everything is beautiful. Women are the same. Every single one of us is really marvelously constructed and very beautiful.

HAIM: I agree. The curves of a woman, it’s launched ships. It created the Renaissance.

WEYMOUTH: Oh, yes.

HAIM: That’s another thing. I get a little prickly when people ask me what it’s like to be a woman playing bass and what it’s like to be a woman in music. That’s part of the reason why we named our record Women in Music Pt. III, because it feels like people are always belaboring this idea. But we’ve never really known anything different. We play music and don’t necessarily know if it has anything to do with our body parts. I love playing music. That’s the beginning and end of it.

WEYMOUTH: That’s exactly correct. That’s exactly what happens. But I do have a question about the dynamics of all female bands. Are they competitive the same way that men are, or are they more supportive? And then, you’ve got siblings.

HAIM: Yes. I was in a band with my parents and my sisters from the time I was 11.

WEYMOUTH: Wow, that’s so cool. That’s like The Cowsills.

HAIM: We were like The Cowsills. Exactly.

WEYMOUTH: I saw the Cowsills.

HAIM: Oh, wait. I saw the Cowsills too! They played a fair that we played every year in the San Fernando Valley. We’ve technically opened for them.

WEYMOUTH: I saw them in Iceland. In Keflavík. Because I was on the bass, I was a service child, and they paid. It was pretty fantastic. We could get really close.

HAIM: Oh my god. That must’ve been so cool. Were your parents music lovers?

WEYMOUTH: Well, they would’ve been if they could have. They loved music, but we didn’t really have instruments around because we traveled. I think they moved 35 times in 33 years. But my grandfather had a beautiful tenor voice and he played piano beautifully. He had a grand piano in his living room in France, and he was a doctor. So I fell in love with music when he played and sang. It was the most important thing, the music, the emotion, and his hats. He always wore fedoras. He was also a really good heart specialist. He did the first open heart surgery, massaged a heart back to life. He became quite a researcher and writer, too.

HAIM: Wow.

WEYMOUTH: When I was young, I developed asthma, so I wanted to play bagpipes. Because I encountered a woman on a beach in Amagansett. It was in the early morning fog and there was this amazing sound. I was four at this point, and we were on our way to Hawaii. This bagpiper was wading through the water coming towards me and the fog. The mist rose, and I saw this creature with all these arms. She then presented the pipe to me and said, “You want to try?” I was just so intimidated by this creature with tentacles and I seized up. My grandmother said, “No, it won’t be the bagpipes.” She had a flute made for me in Paris but I never could have lessons or join band because I was always on the move. Eventually, I would learn to play that flute. My sister, Leticia, was taking it in school because, for once, my parents spent three years in the Washington DC area. So every time she’d come home with her lesson book, I’d say, “Okay, show me what you learned.” And then she would show me what she learned and we did little duets together. It’s an amazing thing to play different instruments. Chris asked me to be in the band and he said, “You could play your flute.” And I said, “Nope.” I just had images of Jethro Tull. I just said, “No, no, no. It’s a beautiful instrument, but it’s not a rock band instrument.”

HAIM: I share the sentiment, by the way.

WEYMOUTH: I’m really diminutive, so I wanted this big, big thing.

HAIM: Something you could really put your hands on.

WEYMOUTH: Well, I love the sound. If there were a classical instrument, it would be the cello. It’s so beautiful.

HAIM: Do you have any favorite memories from being on tour? Do you like touring? Was that enjoyable for you?

WEYMOUTH: I’m glad to not be on tour now. We just toured to death, and you get that kind of burnout. My younger son, he’s a painter, but he’s also a musician. His wife is part of an electronic duo called Xeno & Oaklander and they did a tour in a little Subaru Crosstrek. They covered 11,600 miles in 31 days. They said the only way they could do it is by not drinking any alcohol. They only drank things like Red Bull and espresso and a lot of water. I really think that that’s what hurt touring for me, the amount of drugs around us. It was great until the drugs came into the picture. When we were touring in the 80s, the drug of choice was primarily cocaine, which was cut with all sorts of things, including speed. It made people feel like they could just do anything. But it was just so damaging. I couldn’t do it, because I just didn’t have the health for it. In Stop Making Sense, in fact, that was the first time with the big band that I could be in a dressing room separate from the men. I’m sure you’ve had [similar] situations. I’ve had to change in cars and in porta potties.

HAIM: Oh, yeah. You’ve got to be scrappy.

WEYMOUTH: It was really a luxury to not have to think, “Oh gosh, how am I going to change in this situation?” In the early days, I just wore the same thing on stage as after, so it wasn’t such a problem. That was the fun part, before drugs came in.

HAIM: Do you think it changed people’s demeanor and who they were as people?

WEYMOUTH: Yes, absolutely. In fact, shortly after that, in 1985, I met a woman named Imal. She was extraordinarily psychic. She told me that entities, not good ones, don’t have life, they don’t have sentience, they don’t have bodies. And they enter into people’s bodies when they’re not really all there and it changes people. It makes them different people.

HAIM: Oh my god. Maybe now I’m not going to get drunk after the interview. I will say, my sisters and I, people have this idea of us that we get wasted on stage. Not true. We’ll have a drink here or there, but it’s not like we’re throwing TVs out the hotel window because we’re so drunk.

WEYMOUTH: Yeah, yeah. And it’s so passé anyway.

HAIM: I agree.

WEYMOUTH: Those people who did that are all dead. People don’t even remember their names anymore. It’s not the way to go.

HAIM: I agree. I think there’s something to be said about longevity and treating this like it’s a profession and a career and taking it seriously while still having fun.

WEYMOUTH: Oh, there are so many ways to have fun without damaging the body.

HAIM: To me, I get my jollies when I’m on stage. The armor is my bass and everything else fades away. I can just do and be whatever I want.

WEYMOUTH: That’s excellent.

HAIM: That’s the most fun. I’m sure you had the most fun being able to do that with your husband and Tom Tom Club, too.

WEYMOUTH: Oh, yeah. Well, one time, we were on stage in an arena in Athens. Nobody was allowed to be on the soccer field because that was the precious grass. They set up the stage facing five tiers of bleachers and that was it. 4,000 or 5,000 people paid to come in. I think it was like 25 cents per person, and 20,000 knocked down the fences.

HAIM: Oh, god.

WEYMOUTH: I was five or six months pregnant, so my bass was literally my shield. Apparently, fans there like to throw drinks. This is how they show their appreciation for soccer stars. They thought it was cool to do that.

HAIM: Not cool.

WEYMOUTH: This was 1982. I was using my bass as a bat. But, like you, I felt protected in that moment, and I wasn’t afraid. I should have been, but I wasn’t.

HAIM: Because you felt like you had armor.

WEYMOUTH: I just felt sad. Anyway, it wasn’t cool, but we learned a lesson and we never went back. Este, when you guys sit down to write your songs, do you jam, or does somebody come with a kernel of an idea and then everybody else fleshes it out?

HAIM: I was going to ask you the same thing. But with us, it usually starts with a drum beat. Because all three of us are drummers, we usually start jamming on drums.

WEYMOUTH: Cool.

HAIM: Or we’ll get out a LinnDrum or some kind of drum machine. We have a plethora in the studio. And then we’ll pass the mic around and we’ll start singing melodies over drums, without any bass or a guitar. Everything is super percussive with the way that we write melodies and the way that we write lyrics. From there, we’ll kind of Mr. Potato Head the best bits of what we come up with and meld them together. What about you?

WEYMOUTH: When it was with Talking Heads, like with Psycho Killer, David [Byrne] had an idea with his guitar. He had a chorus and the first verse. But drums are pretty key, especially in all of our songs. With Talking Heads, improvising would start with the rhythm beds. Even in Tom Tom Club, that’s how we write. I started trying to write in a traditional way with a guitar like a singer-songwriter. But I always thought that collaborations in bands are so much more original and interesting than singer-songwriter. Singer-songwriters can be fantastic, lyrically, like Bob Dylan or Tom Petty or Neil Young. Those people, they’re poets first, and music is just barred accompaniment. But with us, the music carries the emotion, and the lyrics are more or less just intellectual ideas that are much more abstract. I try to keep it simple with the bass, especially with Tom Tom Club, because I’m often singing at the same time. I won’t say that I specifically write so that I can sing at the same time. I usually create the bass part and then say, “Oh my god, how am I going to sing with this?”

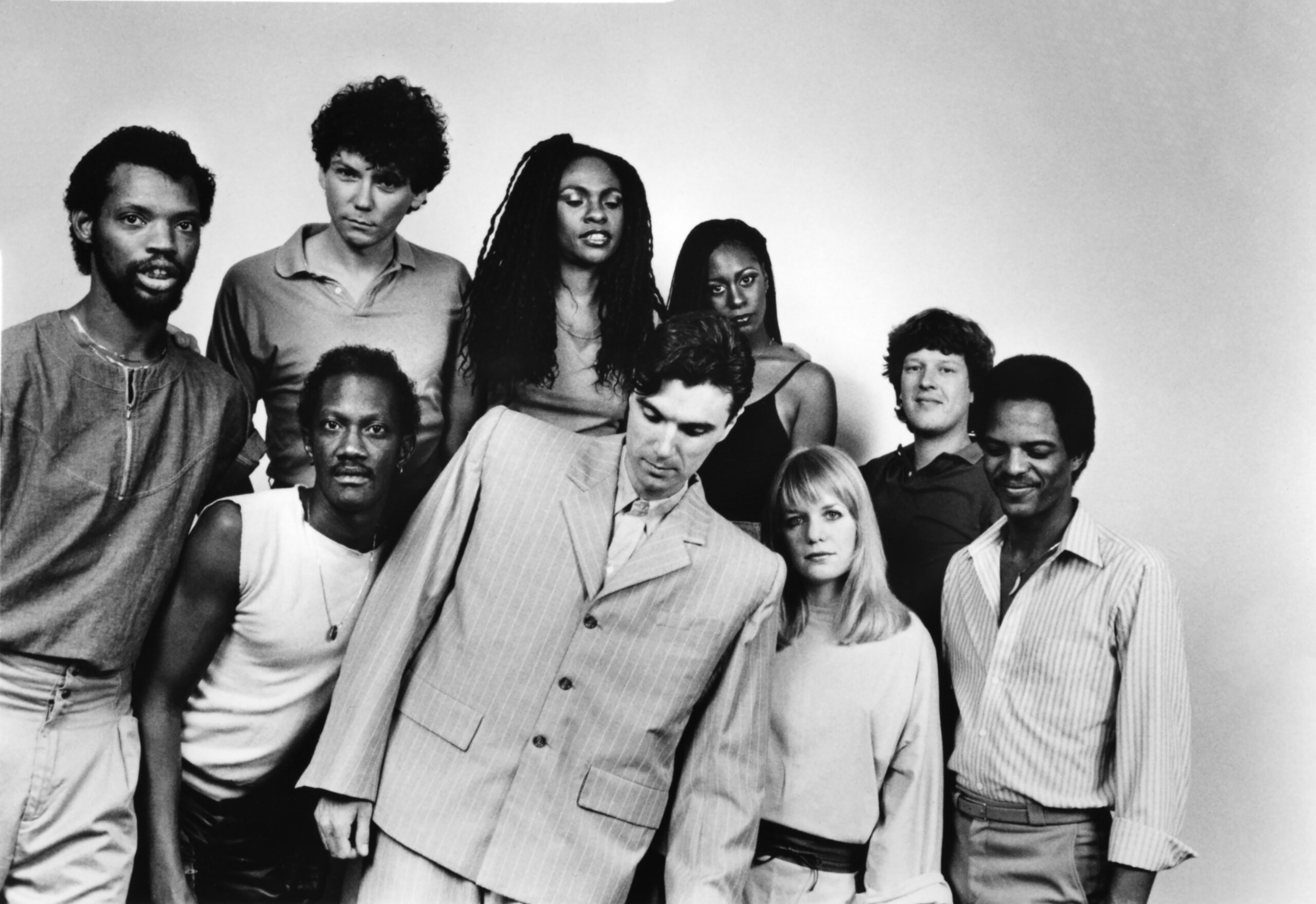

1984: The Talking Heads line-up for the concert film Stop Making Sense (L-R Steve Scales, Bernie Worrell, Jerry Harrison, Ednah Holt, David Byrne, Lynn Mabry, Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz and Alex Weir) pose for a portrait in 1984. (Photo by Sire Records/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

HAIM: I feel the same way.

WEYMOUTH: I always say, “Oh, Paul McCartney could do it. I just have to practice, practice and practice and think of Paul.”

HAIM: It’s not easy. It’s not like strumming.

WEYMOUTH: It’s so different from playing guitar.

HAIM: I agree. It’s really hard.

WEYMOUTH: I played guitar long before I ever lifted a bass guitar. I thought it was going to be very similar, but it’s completely different.

HAIM: Completely different. Even in Haim, there’s times when we’ll write songs and I’ll write a bass line, and I’ll look at Danielle and Alana, and I’ll be like, “I’m not singing this one.”

WEYMOUTH: But that’s what collaborations do. You decide, and that’s the way it should be. That’s successful and smart.

HAIM: It’s really an exercise in care and trust. You really have to trust the people that you’re collaborating with that they’re not going to judge you—

WEYMOUTH: You can’t have the judges there when you’re creating. You do have to have critical functions afterwards. I know people who are just creative and have no critical ability at all. That’s why they need collaboration to say, “Hey, dude, that is not cool. Don’t do that.”

HAIM: “Let’s reel it in a little bit.” I almost admire people that can just sit in a room by themselves with a tape recorder and pluck out a song from start to finish. I’ve never been able to do that.

WEYMOUTH: That’s like Maria McKee or Sheryl Crow. I think they’re just genius at it. But the best things are collaborations. I once asked Annie Lennox how she and Dave Stewart put together songs for the Eurythmics. She said, “One person comes in with an idea, 70%, and then the other person really improves it with the 30%.” That’s how it begins. And then, of course, in the end, it’s 50-50. I’ve met people who think that Paul McCartney did everything because he is such a genius. But I tend to think that that’s wishful thinking. Yes, he can do everything and he has at times, but the very best things were collaborative works.

HAIM: The proof is in the pudding with Tom Tom Club and with the Talking Heads. The music that you guys made together in both bands was so transformative for so many people and for so many musicians. Especially, speaking from my own experience seeing the way that you play and the space that you use was so tasty and funky and magical.

WEYMOUTH: Until it wasn’t. Sometimes it would be a really blocky song, and the lyrics almost dictated that it’s going to be a clunker. Like, “Okay, we know we’re taking the piss in this song. We can’t take this too seriously.”

HAIM: Can you recall any songs in particular where you felt like that happened?

WEYMOUTH: I think it was maybe on our second Talking Heads record. “I wouldn’t live there if you paid me to.” “Big Country” was the name of the song. It starts off very melodic, but then the chorus just totally takes the piss out because it’s just like, “Goo-goo, ga-ga-ga.” It’s just horrible. That was the point of it, I suppose. That was a jerk point of view, but it’s super limited and narrow.

HAIM: I think when you’re young, especially if you’re artistic, you crave city streets and going to museums and metropolitan life. I can relate to that song in the sense that I never got to live in New York. That’s probably my biggest regret.

WEYMOUTH: Well, it’s no longer what it was. Giuliani, he ruined it.

HAIM: Such a schmuck.

WEYMOUTH: So a lot of artists moved. All the gays went to South Beach in Miami. A lot of people just left. It was no longer a viable, creative place. I think we were so lucky in our day. We went there because Andy Warhol was there with The Factory. Lou Reed was there with John Cale and the Velvet Underground. The New York Dolls were there and we thought, “Oh my gosh, there’s such a variety here.” You can do it all with very little. Have fun with no money. People lived it like that. It took me a long time to realize how racist our country was. When you grow up in the service, you don’t see those things so much. But I am seeing it now. Now you see how the systems are set up. I didn’t even know growing up that veterans coming back from World War II didn’t get hospital care if they were Black or female. It affects us as women, and we’re very conscious of it because we see how we’re basically second-class citizens.

HAIM: The thing that I’ve been thinking about as a woman who’s 37 is my reproductive future and what my children’s reproductive future is, especially in this country. I want to have kids, but I don’t know when I want to have kids.

WEYMOUTH: Well, get your eggs now. You know they’re going to harvest more than they tell you, but get your eggs while you can.

HAIM: Yes, I’ve done that.

WEYMOUTH: Oh, good. So smart. This was not a possibility when I was a girl and neither was abortion. It was terrible. People don’t get it, but back in the day, we were just supposed to put up and shut up. I think the MeToo movement has been incredible and wonderful. And without the civil rights movement, we wouldn’t have had a Me Too. And without the MeToo, we wouldn’t have had unions saying, “Enough is enough.” And you will have happier men. They won’t have to be masters of the universe. But they don’t get it because if, they go to business school, they’re taught all the wrong things. They all think like Ayn Rand.

HAIM: Right, The Fountainhead.

WEYMOUTH: They all think that it’s all about number one and survival of the fittest. It’s very Machiavellian. So the saving of the planet is really going to come down to the women. The youngest and most effective general in history was a 17-year-old named Joan of Arc. She effectively ended the Hundred Years’ War. But what do we learn in history? What would they have us learn with Alexander the Great or Caesar?

HAIM: Of course. Growing up, my grandma would say, “Your grandpa might’ve been the head of the household, but I was the neck.”

WEYMOUTH: That’s right! That’s in my Big Fat Greek Wedding.

HAIM: Yes. And my grandma said the same thing.

WEYMOUTH: We share a great deal of common ground.

HAIM: I don’t want to belabor the point, but I’m so honored that I even get to be on the phone with you. You’re such an inspiration.

WEYMOUTH: Oh, Este!

HAIM: I’ll get emotional if I keep talking about it. But you really changed my life.

WEYMOUTH: Good luck with everything. Sleep tight. Don’t let the bedbugs bite. I hear they’re in Paris, so I’m hoping that you’re in a very good hotel.