Vienna Fingers: Wolfram Plays Well With Others

WOLFRAM. PHOTO COURTESY OF ELSA OKAZAKI

Vienna’s Wolfram is a DJ and producer most in the worlds of house and disco would envy. The globetrotting artist has made a name for himself over the past seven years by putting out a slew of high-energy dance music of the highest production caliber (he studied audio engineering in Austria) that instantly infects listeners at home and on the dance floor alike. Over the past year or so, the man formerly known as Diskokaine has had a maturation of sorts, though: he just released his debut full-length under his birth name on Permanent Vacation and is now touring the world, throwing release parties in all sorts of venues, from tiny New York City Chinatown karaoke bars to massive Athens nightclubs. We spoke with the man about his career so far, his hook-filled, pop-leaning LP, modular synths, and the unusual sources of his inspiration.

NIK MERCER: Let’s start with the beginning. What got you into music?

WOLFRAM: I think it was my dad. He always played me synthesizer stuff. Electronic stuff like Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Art Of Noise. He used to build loud speakers, and he always tried them out with loud electronic music. I think that’s why I like it—I grew up with it. Where I’m from, there were no record stores… there were just flea markets, and they had all this cheap Italo disco. I grew up close to the Italian border, so all cheap Italo records wound up there. I always played the dub versions because I hated the vocals, though. But I liked that spacey-sounding synth style. With producing, I went to an audio engineering school, at which I got an audio engineering diploma. When I started there in 2001, I began making music with synthesizers and computers.

MERCER: Where was that school? Vienna?

WOLFRAM: Yeah—I moved to Vienna for school. I lived about four hours south of Vienna growing up. A little village.

MERCER: Is Wolfram Amadeus your real name?

WOLFRAM: No. Wolfram is my real first name, but my last name is Echert.

MERCER: So why’d you choose Amadeus?

WOLFRAM: I don’t know. When I joined Facebook, I looked for a name that wasn’t my own. I didn’t want to tell everyone my own name and was always afraid of the tax office. I wanted to make it harder for them to see where I was DJ’ing or something. So I went with Wolfram Amadeus—but I never released music under that name.

MERCER: And you used to go by Diskokaine.

WOLFRAM: Yeah—I used to release music on Gomma under that name. There was an ’80s record called Discocaine. I wanted to avoid problems, so I used “k” [instead of “c”]. I was 20, 21 when I started using it. I thought it was a catchy name, but now I feel bad for using it. It’s weird how you change so much when you grow older. I think more about what other people think of me… having “cocaine” in my name isn’t that good. And, I mean, the disco thing changed all of a sudden. In 2004, there wasn’t much of a revival going on. Now it’s more trivial. I don’t want my first record coming out under Diskokaine. Like, I might want a family in 10 years or something, and I can’t have “disco” and “cocaine” in my name.

MERCER: Not the best thing to have your kids listening to.

WOLFRAM: Yeah. [laughs] I’m not smoking cigarettes or doing drugs, either.

MERCER: You’ve been making music for quite a while—what compelled you to make this record now?

WOLFRAM: I have always made [individual] tracks, but they were usually sort of jokes. Producing music for me [used to be] primarily sampling and stealing. I never wanted to spend more than one afternoon on a track. Now I want to make proper songs, a proper song-based album. I guess I wanted to start making pop albums that are influenced by the electronic music of the past 40 years.

MERCER: You’re definitely a collaborative artist. Basically every track on the album features someone else. Why do you go about working on music like that?

WOLFRAM: The main reason was because I don’t sing. The only track [on the album] that doesn’t feature a singer is the one with Patrick Pulsinger. The track with Holy Ghost!, for example, was really done [as a team]. I mean, I had the melody as the main hook in a song I put out on Gomma (“Hall Of Shame”) and Alex [Frankle] from Holy Ghost! was like, “This is such a great tune—you should make a song out of it that I can sing on.” So we went to their studio and worked on it.

MERCER: It sounds like Holy Ghost! did more than just write the lyrics. There’s that typical anthemic, triumphant vibe to it.

WOLFRAM: Yeah—like I said, it was out before on Gomma as “Hall Of Shame.” The rest of the album… I just did all the instrumentals and asked people to sing. Like Andy Butler and Kim Ann Foxman [from Hercules and Love Affair]. Or Paul Parker. I never met Paul, though. I just sent him the instrumental and asked him to send the vocals back.

MERCER: So how long did it take to make the album?

WOLFRAM: It took something like eight months, but that was mostly because it would take a few months for [contributors to come to Vienna]. Like Haddaway… it took him three months or something. He had sung his vocals on my answering machine because I didn’t see he had called. He was like, “Hey, Wolfy—this is Haddaway. Thanks for sending me the instrumental. It should be like this.” And then he pushed play and started singing over [the instrumental track]. But it took him three months to get to Vienna! With other guys, like Andy—he recorded the first verse in January, but then went on tour, so he couldn’t come back until two months later, which is when we also recorded Kim Ann’s vocals.

MERCER: Jacques Renault was telling me that you work off of your computer a lot.

WOLFRAM: All of the melodies I make with MIDI with plugins, so I can run them through the synthesizers. Since I’m on the road [a lot] and oftentimes get ideas after parties… after listening to other DJs. But I lose those melodies after, like, five minutes, so I usually sing them into my iPhone and then try to replay them on my laptop [later on]. Then I plug in my MIDI interface to the modular. I don’t care if it’s a soft synth or not. I’m not a super nerdy guy who’s like, “It must always be the modular synth” or “It must be some old Roland” or whatever.

MERCER: Why did you come over to New York originally? You’ve been living here for a while on and off.

WOLFRAM: Because in 2004 I was going there. That was when I first DJ’d with Paul Pulsinger, actually. I was playing a lot of Italo and disco, and this was a bit before the whole revival thing. The promoter at the club was, like, “Hey—I really like your stuff. Can you DJ every Friday at this place in Brooklyn called Cash Checking?” So I ended up DJ’ing there, which is where I met James Friedman [of Throne Of Blood]. I also DJ’d at Happy Ending. So, for three months, I was DJ’ing every second day for, like, $50. No money, but the parties were great, and I know that’s why I made so many friends then.

MERCER: Yeah, everyone seems to know you.

WOLFRAM: [laughs] Well, now I have my girlfriend there, too.

MERCER: Tell me about your graphic design. Both the “Hall Of Shame” single and your full-length have this Japanese packaging motif.

WOLFRAM: I found a Paul McCartney record, a Japanese edition, and I was never a fan of McCartney and never liked his face on record artwork, but I was like, “Ah, fuck—he looks sort of cool [in this context].” So I just took that and started writing “Wolfram” or “Diskokaine” over it. So I stole it from Paul McCartney. Anyway, I licensed the album in Japan and the label there showed me how to write my name in the right way, so now it’s correct.

MERCER: The way that the Japanese package their CDs is so nuts. Those little spine sleeves and whatnot…

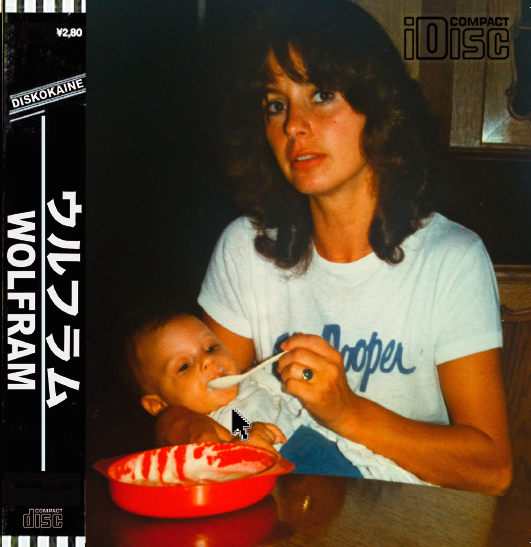

WOLFRAM: They told me that they have a lot of import CDs, so they always want to have something special for the Japanese pressing of an album. [My Japanese label] asked me for a hidden track and different artwork, so for that one, my face is on the cover, not my mom’s.

MERCER: Why did you choose the photo of you and your mom for the cover?

WOLFRAM: That was meant to be on the back side. I sent a family photo to Permanent Vacation, asking to use that as the cover. I said, “If the album’s going to be a flop, at least my family will be happy since they’re on the cover.” But then Permanent Vacation was like, “Hey, the back side is better [for the front] because your mom is hot and your dad’s not.”

MERCER: You have a good-looking mom. And the photo’s awesome.

WOLFRAM: I was just a few months old… Oh! So that’s funny. One of the Vampire Weekend guys came to the Let’s Play House release party [on April 9], but he couldn’t get in. So he texted me and asked me to bring him in. I didn’t see it and asked him to dinner the following day [to make it up]. He told me that they got sued for their album artwork. I guess they found the photo on Flickr and asked the owner if they could use it for their album. He wrote back, said he made the picture, and claimed that [the model] was his ex-wife from the ’80s. So he did the paperwork and [forged the model’s signature], but she doesn’t even know the guy. Now she’s suing Vampire Weekend for two million.

MERCER: I read about that. She was a magazine model or something in the ’80s.

WOLFRAM: Well, Vampire Weekend already has insurance to protect them from lawsuits, so they’re fine. They’re suing the photographer back, too. [laughs]

MERCER: At least you’re using your mother as the model. I doubt she’ll sue you.

WOLFRAM: Yeah, but she wasn’t that happy when I did it. I never told them I was going to put it on the cover. I got the promos from Permanent Vacation around Christmastime and thought I’d surprise my mom by showing it to her. She was like, “Oh, is this a joke? It’s a promo so you can change it, right? We think it’s better for your career to have your face on the cover.” They just want the best for me.

WOLFRAM’S SELF-TITLED DEBUT ALBUM IS OUT TODAY. FOR MORE ON THE ARTIST, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.