Tom Waits

Tom Waits writes great songs and sings them with greatness. He made his first album ten years ago. It was called Closing Time; he has been open ever since. His new album Swordfishtrombones (Island Records) is his ninth. His songs have also been recorded by others including the Eagles, Manhattan Transfer, Bette Midler, Richie Havens, Jerry Jeff Walker, Martin Mull and Barbie Benton. His score for Francis Ford Coppola’s One From the Heart was nominated for an Academy Award. He has also acted in three of Coppola’s films: The Outsiders, Rumble Fish (and the forthcoming extravaganza Cotton Club.)

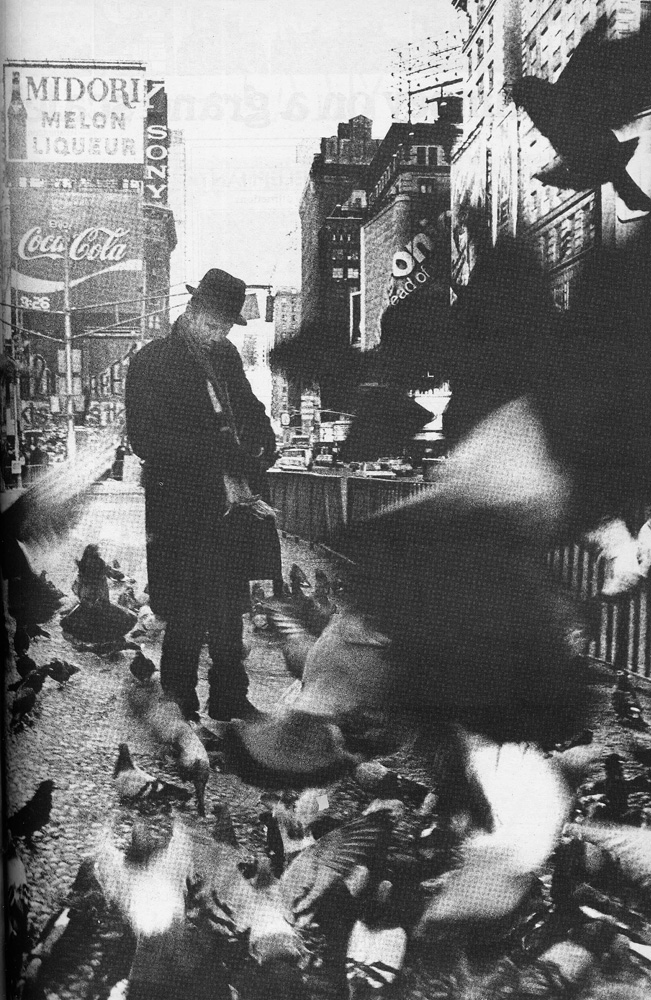

Waits looks like a character actor, probably because he has character. It shows on his face and you can hear it in his voice. He looks like Sam Shepard’s description of the older brother in “True West,” except that his clothes are clean and he wears socks with his pointed shoes. When he sings his voice sounds like it could kill your canary or shatter adobe or crush a Miller Lite can, but when he talks he speaks softly. Like Teddy Roosevelt said, “Speak softly and sing like a big stick.”

GLENN O’BRIEN: Have you lived in California your whole life?

TOM WAITS: No, I’ve lived in other places. I’ve lived in Arizona, Florida, Seattle, New Mexico for a while… National City.

O’BRIEN: Where’s that?

WAITS: Southern California. It’s predominantly a sailor town, outside San Diego on the water. I live in downtown Los Angeles now. It seems to be the most convenient place for me. I lived in New York for a while, at 22nd and Eighth, but it didn’t last very long, about four months.

O’BRIEN: What other jobs have you had besides working musician?

WAITS: I was a fireman.

O’BRIEN: Did you go to fireman’s school?

WAITS: Yeah, after a fashion, kind of on the job. In the middle of an emergency I was being trained for one. It was right on the border between California and Mexico and most of the fires were on the other side of the fence. You’re not allowed to put ’em out. It’s frustrating. I lived in the fire station for about a year. The pay wasn’t so good. It was kind of like being in the army, or what I imagine that would be like.

O’BRIEN: Did you ever get smoke inhalation?

WAITS: No, they’d show you these techniques—like digging a hole, getting in it, and pulling the dirt on top of you, let the fire burn past you. It wasn’t good for my nerves, that kind of work. I’ve got high blood pressure. I get upset easily. I don’t think that was a proper career alternative for me.

O’BRIEN: What were you doing right before you started playing music professionally?

WAITS: I was working at an Italian restaurant. I never looked at music as a serious venture. There was very little encouragement from my family. I didn’t have anybody to entertain, so it was hard to get motivated. I used to play in a small club called the Heritage in San Diego. It was like a coffee house. I just played by myself.

O’BRIEN: Did you do the coffee house circuit?

WAITS: I didn’t play in too many places until I got a record out. That made it possible financially.

O’BRIEN: When you did go out on the road did you play in the same places with rock bands?

WAITS: I played small rooms, 250-seat clubs. Eventually I went out as Frank Zappa’s opening act. It did absolutely nothing for my confidence. It took the low opinion I already had of myself and diminished it. But there were positive aspects of it I did enjoy the challenge of it nightly.

O’BRIEN: Do you find that the fans you meet often have a radically different idea of what you’re like from your own?

WAITS: Invariably. A certain amount of that is cultivated and a certain amount is not.

O’BRIEN: Do you enjoy misleading people to a certain extent about what you’re like?

WAITS: I don’t think it’s a question of misleading. I think it’s the difference between a deposition and a discussion.

O’BRIEN: I didn’t mean misleading in the sense of fooling people as much as performing a little personality sleight of hand.

WAITS: I don’t think that you should be perfectly candid and frank about the intimate details of your personal life with the public at large. Subsequently, it creates considerable personal problems. I think you have to keep a certain amount of your life very private. Don’t you agree?

O’BRIEN: Yeah. You have a strong public image with a pretty large public. I think there’s a tendency to react against your own image as soon as it gets to a certain saturation point. If everybody in America thinks you have a four-day growth, you better shave for a while.

WAITS: Yeah, I think you have to just as a question of survival. Unfortunately, I made the mistake at one point of putting my address on the back of one of my albums, just to find out what would happen. I received a lot of disturbing mail and calls. Actually, I was living in a hotel, so it was easy enough to find the number. I got a kick out of it for a while. Then I realized what I’d done.

O’BRIEN: Did anybody just show up?

WAITS: Yeah, a lot of people showed up, most of ’em certified… So now I am much more private.

O’BRIEN: You did music for One From the Heart. Did you do music for another Coppola film that hasn’t come out yet?

WAITS: No. I had a small part in Rumble Fish. I played a kind of retired Hell’s Angel-type in it, the proprietor of a pool hall called Benny’s. I’m like a Doc-in-the-malt-shop kind of character: “Knock it off! Get your feet off the seats. Watch the language!”

O’BRIEN: Was that the first time you ever acted?

WAITS: No, I’ve done real small things in a couple of other films. Paradise Alley, where I essentially sat at a piano for three weeks, and another picture called Wolfen, and they cut that out.

O’BRIEN: What were you in Wolfen?

WAITS: I sat at a piano. I’ve got an opportunity to work with Robert Duvall in a picture in Montana in July. I don’t want this to sound like an advertisement for myself, but this is what I’ve been up to. It’s with Fredrick Forrest and Glenn Close. It’s called Stone Boy. It’s about a young boy, twelve years old, who accidentally shoots and kills his brother while out hunting, and how it affects the family and the community and his life. He runs away from home and, meets up with a guy who works for a carnival, who is a sideshow freak…

O’BRIEN: Is that you?

WAITS: Yeah. The Petrified Man.

O’BRIEN: Are you supposed to have some disease or are you faking it?

WAITS: It’s a carnival thing where they put you in a yellow jockstrap, strap you down to a table, turn the lights down and people can come in and look for a dollar.

O’BRIEN: Do you have a way of working when you’re writing songs?

WAITS: Lately I’ve become more disciplined. When I worked for Coppola I shaved, put on a suit and tie and went to work and sat in an office. That experience helped me become more disciplined about what I do.

O’BRIEN: Did they leave you alone in your office, or was it a busy atmosphere?

WAITS: I was on a long hall with typewriters going off and a certain kind of frenzy—carpenters, memos being shoved under the door, people calling on the phone and banging outside in the hall. I liked being part of a project. It was like sewing the buttons on this huge sport coat. For this album I sat in a little room—I moved in some kettledrums, a B-3, a marimba and some stuff to bang on, a tape recorder and a bottle of Squirt.

O’BRIEN: In Coppola’s latest you play the owner of the Cotton Club?

WAITS: Herman Stark, yeah. The manager.

O’BRIEN: A real person, I guess.

WAITS: He died in 1981, in Florida. His brother Lewis Stark operated the cash register at the Cotton Club. Herman was areal show biz-type entrepreneur. He was the manager of the club, overseeing most of the club’s activities. Tuxedo, cigar. He answered only to Onie Madden, who was the owner of the club. He’s kind of a sheepdog in a tux.

O’BRIEN: There’s a place called the Cotton Club now at 125th St. and the West Side Highway—is that the same location?

WAITS: No, this was 142nd St and Lenox Avenue. But there may be some of the same people associated with the original Cotton Club. I don’t know.

O’BRIEN: Is Stark a big part?

WAITS: It’s not a big part, but it was a long haul. A ten-week stretch, all shot at Astoria Studios on a sound stage where they reconstructed, based on photographs and chronicles, a remarkable replica of the original Cotton Club.

O’BRIEN: Was anybody from that scene there advising?

WAITS: There were some old-timers brought in as technical advisors—original cast members.

O’BRIEN: Did they tell you what Herman Stark was like?

WAITS: They said he was elegant, well-spoken, a gracious host, very kind, understanding, tough when he had to be. Good with the girls backstage, always on time, but always took as much time to take care of one of the chorus girls who had a problem with a boyfriend as he would to greet Gloria Swanson at the door, or take a message to Frenchie from Onie Madden or break up a fight. He had to do everything. I mainly did the film so that I’d have a chance to work with Coppola again—it’s always uplifting and I learn a lot. He’s completely unconventional. He has a strong sense of loyalty. Great eyes. It’s a diabolical undertaking in terms of organization and leadership.

O’BRIEN: It’s a musical?

WAITS: It’s a gangster musical. Rich, last Ellington is really the score, and Cab Calloway, Ethel Waters, Lena Horne. The dancing is just unbelievable.

O’BRIEN: Do they have people cast as Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway?

WAITS: Yeah, look-alikes. Gregory and Maurice Hines, Diane Lane and Richard Gere are the stars. Bob Hoskins plays Onie Madden and Fred Gwynne plays Frenchie.

O’BRIEN: Yeah, I have a feeling that this is going to be the one that…

WAITS: Buries Coppola?

O’BRIEN: No, puts him back on top.

WAITS: It’s a very important period of American history. The end of the ’20s, the Crash. In terms of black music—the only music that we can call our own, that was really born here—I don’t think a lot has been done to chronicle the relations between American history and where black music fits in.

O’BRIEN: Do you have regional popularity?

WAITS: At the risk of sounding presumptuous, I have little pockets of enthusiasm throughout the world. Uh, let’s see. . . I do well in Belgium, New Zealand France, Norway, Finland…

O’BRIEN: It’s funny, they really seem to go for great English lyricists in countries where English isn’t the language. I’m not talking about New Zealand.

WAITS: Yeah, I was shocked to be performing, in Osaka, but I guess beyond the mundane vernacular there’s a place where, hopefully, you can speak to somebody. They like saxophones over there. And upright bass and drums. If they don’t understand the words they can always sit and listen to the saxophone. Just like after you’ve seen Lawrence of Arabia enough times you just watch the camels.

O’BRIEN: You’re going to do a stage show.

WAITS: I’m doing a show that’s tentatively titled Frank’s Wild Years, based loosely on the character in the song of the same name on the record. It’s going to an American story of redemption and struggle for meaning, spiritual fulfillment. About a man obsessed with air conditioning and trains and on a journey against the American landscape. One heart beating in a digital world. It’s a musical.

O’BRIEN: Are you going to use more from Swordfishtrombones album?

WAITS: Some. But I’m trying to write a lot of new music for it. Half the show will be narrative and ultimately I’ll assume character of Frank in various production numbers spotting the libretto throughout.

O’BRIEN: Are there other players involved?

WAITS: Some. Musicians and a chorus—three background singers. I don’t know where it’s going to be put on. Hopefully in a tabernacle. Essentially it’s a story about a guy who grows up in a small town, very frustrated, joins the Merchant Marine and comes home and marries the girl he had told before he left, “Think of me as if I was dead,” and she waited for him in spite of that and they settle down and the whole thing falls apart and he burns the house down and leaves—he goes out into the world looking for a new meaning, a fulfillment with what time he does have left. It’s an adventure.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE MAY 1984 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.