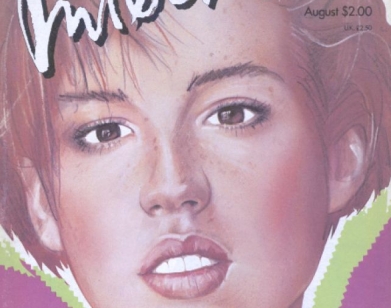

seventeen candles

Sharon Van Etten Shows Molly Ringwald Her Resting Sad Face

Photo courtesy of Sharon Van Etten.

Sharon Van Etten has staked a decade-long career on her vast emotional reservoir. Over six confessional folk rock records, Van Etten has charted a path from her DIY origins as a young songwriter working through an abusive relationship at Brooklyn open mics, to her status as a rock beacon writing and recording albums from the sanctuary of her in-house Los Angeles studio. Though a lot has changed for the New Jersey native—the subway tracks clanging in the background of her earliest records has been replaced by California birdsong—a lot also hasn’t. For the 41-year-old artist, the trials and tribulations of coming of age still feel fresh. Last week, Van Etten released her latest album, We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong—a record that hums with the same yearning and solitude as the artist’s earlier work, but with a more cryptic and intimate lyrical backbone. One person who can’t get enough of the record is Molly Ringwald, the Brat Pack veteran and longtime fan of Van Etten’s music (and acting). Here, the pair discuss the aches and pains of adolescence, their mutual fandom, and what’s hiding in the lyrics.

———

SHARON VAN ETTEN: Hi, Molly! Thanks so much for doing this.

MOLLY RINGWALD: It’s such a pleasure. I’m a really big fan, and I even asked you to let me use one of your songs for a little film that I did. I have to tell you right off the bat that I love your new album.

VAN ETTEN: Thank you. You have been a role model of mine since I was a kid, and we met at a time in my life when I was finally getting my act together-ish. I was in a settled relationship, about to have a child, and I was looking to people that had managed to make it work without compromising their creativity. You’re an inspiration.

RINGWALD: Thanks, I’m literally figuring it out day by day. You said something in an interview that stuck with me. You said that when you think about the future, you get anxious, and when you think about the past, you get depressed, and that forces you to be in the moment. There’s nothing better than kids for that. You have to be in the moment, or you’re fucked.

VAN ETTEN: That’s one of the mantras that I use guides for myself. Another one is, don’t take anything personally. But I definitely do.

RINGWALD: I saw a post of yours about something a critic said—it was about one of my favorite songs, “Seventeen,” and you seemed so hurt. I jumped in and commented, but I love how open you are about your feelings—you sing them, you write them. My husband always tells me that my superpower is making people cry, and I think that might be your superpower too. I listened to the first song on your new record, “Darkness Fades,” a thousand times, and I’m in tears without fail. Is that a superpower that you’re aware of?

VAN ETTEN: When I first started playing in front of people at open mics, I would drink whiskey to shake the nerves. Lots of it. I used to have this haircut, which I have again now, where my bangs were long enough to cover my eyes and prevent me from making eye contact with people. At the beginning of a set, I would say in my thick Jersey accent, “All I want to do is make someone in this room cry tonight.” At the time, it was my way of making light of what I was actually doing. I write songs when I’m feeling an emotion that I don’t know how to talk about, and I’m usually fighting back tears as I’m writing and recording. Sometimes it’s audible in the songs. When I perform live it can be very visceral, because I still feel so much of it as I’m performing.

RINGWALD: You wrote this album during the pandemic. Did you feel a real difference, compared to your other records?

VAN ETTEN: Absolutely. We moved to Los Angeles just before the pandemic, and my home studio was built just before the first lockdown. My New York studio was a basement that I shared not only with another artist, but also with rats and exhaust from a restaurant. I dreamed of having more space, a yard, my own studio, time for myself. When the pandemic hit, it felt like the universe was calling my bluff. Suddenly, time and space were the only things I had.

RINGWALD: It sounds idyllic.

VAN ETTEN: It helped me nest, it helped me meet my neighbors and feel a sense of community. In that way, I felt safe. As a parent, I felt like I was living a double life, because I knew what was happening in the world, but my kid was three, so I protected him from it. I had to filter this apocalypse for him so that it felt like an adventure. My son remembers that period as a really wonderful time, and it’s going to be pretty wild when he’s older and we reflect on what was really happening. I was inspired, even though it was sparked by trauma. It’s a hilarious record and I think everyone’s going to love it.

RINGWALD: You made this decision not to release any singles. You wanted people to listen to the album in one sitting, and I don’t remember the last album that I did that with. My husband and I just sat on the bed together and listened to the whole thing, and it brought me back to my teen years. I would go to Tower Records on Sunset with my allowance—even after I started making money, I still had an allowance. I remember the excitement of pulling the plastic off a new record, putting it on the turntable, and lying on your back listening to it. This album really brought back those feelings.

VAN ETTEN: That means so much coming from you. I know it’s asking a lot of people to listen that way— it’s easy to get distracted and we’re all busy. It’s more of a challenge to myself—to remember how special those moments are when you have them. Albums are a rollercoaster of emotions, and it’s never about one song. It’s about the journey from the beginning to the end.

RINGWALD: Can you talk a little bit more about that journey? I did two albums, but I was seven years old for the first one, so I don’t think it counts. How do you go about writing an album, and how do you know when it’s done?

VAN ETTEN: I struggle with it still, but I think each album represents a chapter in my life. When I have 20 songs, I listen to them and try to find the common thread. What am I saying? Is this relatable? Why do I want to share this? From there, I make music mood boards of what the instrumentation is going to sound like. For this particular record, I made a playlist, so that when I brought musicians on board, I share it with them and not give too much direction.

RINGWALD: What was some of the playlist of your musical influences?

VAN ETTEN: Scott Walker, Cocteau Twins, Rowland Stuart Howard, Joy Division, Roy Orbison and Celine Dion. Very melodic and orchestral, but also percussive and angsty and intense. It’s a marriage of electronic music and real instruments.

RINGWALD: It sounds incredibly lush in the best way. It feels so layered. Right now, I really love “Mistakes.” I ran upstairs to play it for my daughter—she’s graduating from high school and getting ready for prom and college. She’s ground zero for teen anxiety, and that song is an anthem about learning from your mistakes and embracing them. When you listen to music, do you gravitate towards lyrics or sound?

VAN ETTEN: It’s instrumentation that draws me in, but it’s the first line that gets me hooked. If I I don’t like the lyrics, it’s harder for me to connect.

RINGWALD: Lyrics are so important to me. As a writer and actor, I am always looking at words. Which reminds me, I have to ask you about acting. My husband and I love The OA, and I read somewhere that you were a little bit relieved when it was canceled, because you felt like an imposter. What are your feelings around acting?

VAN ETTEN: Well, I grew up in choir and theater. I was always in the chorus, but I never got a role. I was asked to audition for The OA at a time when I was about to pursue my degree in psychology at Brooklyn College. I remember thinking, “There are so many people who worked their entire lives for a role like this.” I felt guilty that it wasn’t something I’d been working towards, and that feeling never went away. The whole cast was really patient with me, but I definitely wished that I had more experience, because I didn’t know how to approach the work. But my partner was like, “This is an adventure. They came to you specifically, and if you end up being good at it, this could be another path for you.” I had a really great time, but it left me feeling like I had a lot of work to do.

RINGWALD: I thought you were really good.

VAN ETTEN: I have this resting face where I look concerned all the time. I furrow my brow constantly, and my sister always makes fun of me for it. She’s like, “You’re doing it again.”

RINGWALD: As an actor, I didn’t feel any resentment from seeing you, an artist in another medium, on camera. I get where you’re coming from though, because I’m known as an actor even though I started out singing. Whenever I do anything other than act, I get that imposter thing. Maybe I’m just projecting what I’m afraid other people are thinking, but it was always hard for me, and I didn’t get over that until I was 40. At that point, I was like, “Fuck it. I’m 40 now, so who cares what anyone else thinks.” All the writing that I do now ties back to what I’m interested in—emotions and connection.

VAN ETTEN: It’s inspiring to see a creative person try new things. It’s not like you have one job, then you become a parent, and your life is over. You have many lives, and I find that very heartening.

RINGWALD: Are you still going to get your degree in psychology?

VAN ETTEN: I’m chipping away! I never got my undergrad, and I have two more classes. As a transfer student in my 40s, I’m not exactly desirable. Once I get that done, I can apply to psychology programs in California.

RINGWALD: I think it’s so great. It feeds into what you do. My daughter doesn’t know what she wants to study in college. I’m like, “Just do it all. Act, make art, study biology.” It’s all going to make you better at what you ultimately choose.

VAN ETTEN: It will start making sense eventually.