TOUR DIARY

Sax God Masego Makes Music With a Mamba Mentality

Hours before the last show of his sophomore album’s tour, the Jamaican-American musician Masego calls me while taking a stroll in Los Angeles. He sounds relaxed. “It’s a beautiful day,” he says. Later that night, he’ll hit the Wiltern Theater to close out his run stateside before heading to Europe for shows in Brussels, Brixton, and Oslo.

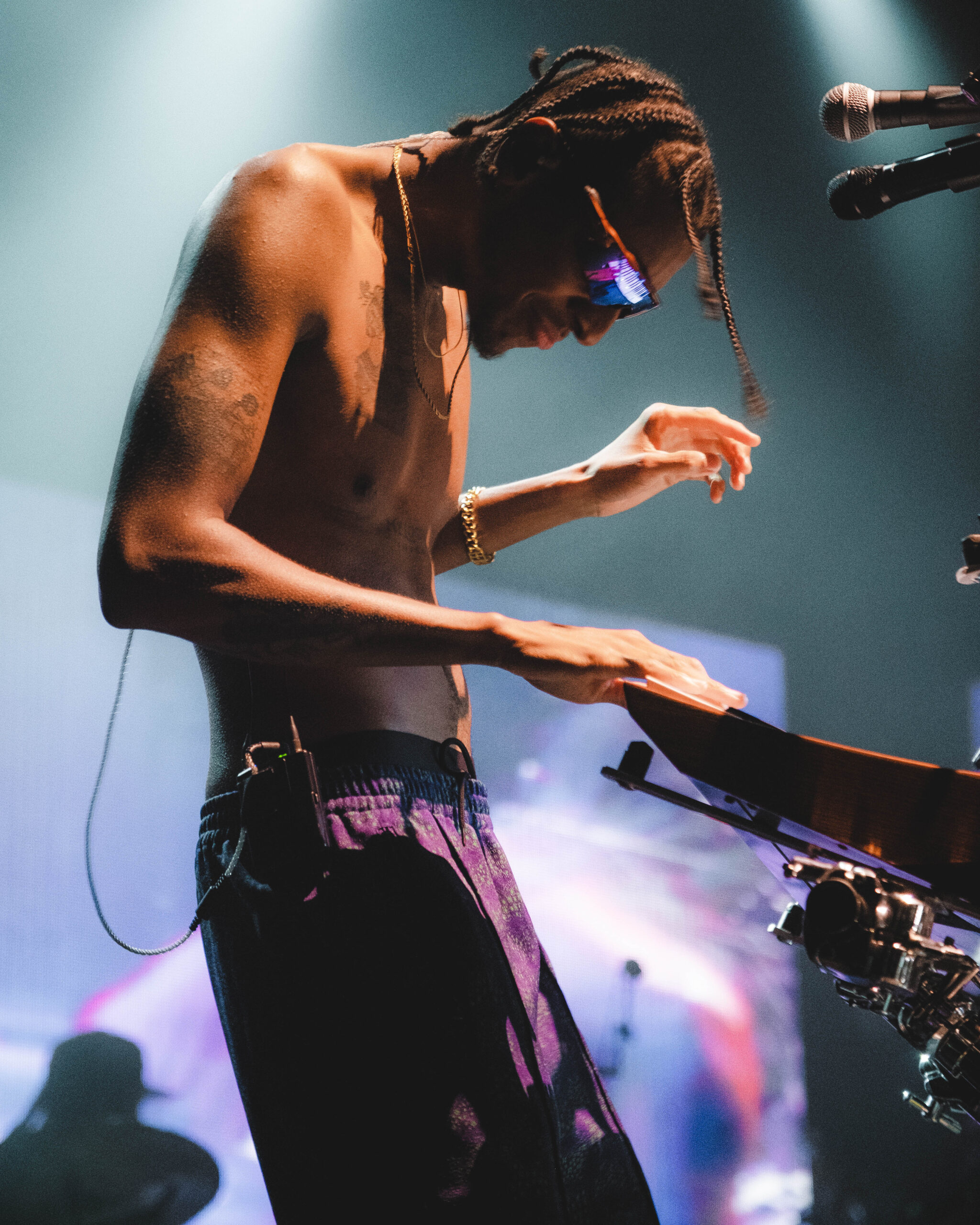

To listen to Masego is not to see him live. With no beat machine to rely on, he’ll disrupt a song to make a quick Middle Eastern-inspired beat in a sudden moment of liberation, then head to the piano, operating purely on instinct. During the set, everyone from the sound tech to the lighting director bounces off one another freely, embodying the spirit of what Masego calls “trap house jazz.” Suddenly shirtless, Masego jumps between beloved tracks both old and new, brandishing his sax above the sea of swaying fans in the audience. The night culminates in the collective encore breath of “Tadow,” the track that started it all in 2017, when his YouTube studio session went viral. But before he took the stage, Masego talked to us about musician stereotypes, getting closer to Africa, and his tug of war with fame.

———

MIRA KAPLAN: This is the last night of your U.S. tour. How are you closing out this chapter?

MASEGO: I think it’s important to celebrate the wins. Tour is my favorite thing because you get that instant gratification when you do good. You get to feel the response. You get to feel less holding your breath-ish. You’re just like, “did I win?” And when it comes to tour, you can understand when you’ve won.

KAPLAN: I was just watching your producer Louie Lastic’s video breaking down the song “In Style.”

MASEGO: Yeah, I love Louie Lastic. He’s a DMV dude. I used to know him from the internet when he was this amazing DJ that was combining genres. That was a point of identity back when I was a youngster. He was known for all these cool beat battles where his beats were so different from anybody else, like real black sheep, real divergent. And those are the people I flock to. Now, in L.A., he’s got this nice studio setup with all these strange instruments. And his aesthetic in his studio is just very East Coast. My favorite songs happen when you forget that this is a job and [we can] make music like we’re teenagers. So the process was kind of, “I’m the kid and he’s cosplaying the adult.” “In Style” happened when I kept throwing random ideas at him and he was just like, “Yo, we could actually sample your high school band, and then we can do this.” And just riffing off each other.

KAPLAN: Your high school band is sampled in that?

MASEGO: No, because that would mean I’d have to pay people.

KAPLAN: That’s true.

MASEGO: It’s just nature sounds made into a marching band.

KAPLAN: What noise was he chasing with those drums?

MASEGO: A marching band has all the elements of a sound wave. You have lows, mids and highs. So you’ve got this big old drum that someone carries in their chest and beats on the side. The snare, that cracking sound, is more of a high thing, treble. And then you have quints and different variations of drums that are inhabiting the entire musical spectrum. It’s gonna get really nerdy. Certain basses are felt in your chest, some lower body, but others are more heady. It’s super spiritual, super African. And the drumline is just an extension of that.

KAPLAN: Guitars too, I think.

MASEGO: There’s a reason that songwriters love to write with the guitar. They’re very in tune with some of the natural tones of how we speak and sing.

KAPLAN: Where in Africa do you find inspiration?

MASEGO: The Mali people and Nigerians are big on drums. South Africa has a huge musical scene. Ghana has a rich history and a connection to Jamaicans as does Nigeria. It’s like playing Connect the Dots.

KAPLAN: You’ve mentioned Brazil as one of your favorite places, too.

MASEGO: I love Bahia, Salvador. I don’t know the stat, but that might be one of the densest populations of Black people in the world. The West African slave trade started there. It feels really Jamaican; they look like my relatives. Real spiritual. That was the first time I went into a drum store and was just jamming with people, it was a very ganja effect.

KAPLAN: Lastic recently mixed funk, too, which originated as protest music in favelas. Now, it’s mainstream.

MASEGO: That’s how it goes, though. Samba is the music of Brazil, but it was banned once. It’s all part of the struggle in the same way that jazz music was Black music, speaking about all that was happening, politically, environmentally, socially. And then it gets diluted into bossa nova and smooth jazz. There’s a lot of depth in how everything gets transported to people.

KAPLAN: Since you’ve been to so many different places, does it make it hard for you to be here?

MASEGO: I just want people to get perspective. I’m not saying everybody has a passport or has the money to go travel overseas. But maybe look on the internet, which is free. And watch something that gives you more perspective. Walk out your crib and observe people. We’re not that dissimilar. When I go overseas to Africa or Brazil, the things that they don’t care about, it just refreshes me. It’s like, “You’re right, that does not matter.”

KAPLAN: Totally. How do you channel that on tour?

MASEGO: When you have the authenticity of, “Yo, I might mess up in front of 1,000 people, I’m gonna just pour something from my spirit”—I think people connect with that. I love the vulnerability and the realness of just creating something in front of people. They know I don’t have a beat machine, I don’t have something written down. This is you and I experiencing this. And that’s what I experience overseas, just somebody playing their musical instrument on the street, not with a hat, not with a QR code. They’re just making music because that’s what they do.

KAPLAN: I wish more live music was like that.

MASEGO: I kind of like that it’s rare. There are only a few people who play instruments and sing. I make these lists all the time. And it’s like, what, Steve Lacey, Bruno Mars, Anderson, and me? I encouraged other people to do it.

KAPLAN: Why do you make those lists?

MASEGO: I’m an ex-athlete, I like to gamify things. I think game theory is healthy. As musicians, our journey is usually just to become the best ever, but I love to spar with my peers. At the end of the day, we’re gonna get love from people regardless. But it’s not about trying to get praise. I’ll just do this little silent battle between me and Smino or me and somebody else because that’s fun to me.

KAPLAN: Some healthy competition.

MASEGO: I love it. I’m a super humongous Kobe fan and everyone speaks about how he mentally just beat them up. I like that it’s kind of a jiu-jitsu thing. They’re all about breaking your will to even want to fight. We’re trying to have a good time, so I’m battling my own band on stage and we’re trying to really level up. And I think that Kobe mentality makes it the greatest.

KAPLAN: I wanted to ask about your band. You play with Ced Mitchell and—

MASEGO: Yeah, Ced Mitchell, genius of a man.

KAPLAN: Who else?

MASEGO: It’s a big list. There’s 14 people. Jonathan Curry on drums, Ced Mitchell on bass, Trill on auxiliary and playback. We have an LD guy, a lighting director, but he’s doing it in real-time, he’s playing it like an instrument.

KAPLAN: How does that work?

MASEGO: Think of it like the MPC [Music Production Controller] where someone’s just playing the drums live but the thing that responds is the lights. He’s a musician, he’s dancing throughout the show, he’s part of the band. Jose, our sound guy, same thing. He’s adding effects to my voice and using his board as an instrument. There’s a lot of people, though.

KAPLAN: It’s a whole production on the fly.

MASEGO: We’re a team of highly chosen people, but also we’re a family. So it’s a beautiful dynamic. We’ve been together for six or seven years.

KAPLAN: What was your first experience in a band?

MASEGO: My first band was a go-go band actually. Truly, it wasn’t go-go, but we called ourselves that. There was this thing back in the day where we would just combine a bunch of random instruments and call it go-go. It’d be a DJ and a violinist and a trumpet player. I think it was an early version of trying to combine genres to create something new. I had no business trying to make a band not even understanding leadership, but we were always having fun.

KAPLAN: You’ve identified with this community of musicians for a while now.

MASEGO: It’s a cool community. My drummer can go to any city and find a shed where drummers are in a room trying to sharpen their skills. There’s like a community within the community. And I understand all the personality types. All piano players kind of hate themselves and think that they’re not good enough, but they’re like, the most fire and the most intelligent. Drummers have this man’s man energy and these uncle’s humongous hands. They usually smoke. I think saxophone players got to get better. Terrace Martin does a great job at uniting the saxophone players.

KAPLAN: That’s your signature instrument, right? What are sax players like?

MASEGO: From what I’ve observed, saxophone players are very sexual and sensual. And also very spiritual and tribal. Once you kind of understand how to really access the tones of your instrument, you start dressing like Kamasi Washington and some of these other cats where you’re just wearing fabrics and you got all these random stones and beads on your neck. I started doing it, too. I got some tiger bracelets on right now. You get closer and closer to Africa and your instrument is like an extension of your own voice. It’s a complicated instrument, 24 keys, and to be able to make music with that while remaining present mentally is like, “that’s a heady person.” You’re moving your hands really fast and you’re very in tune. It’s like a dancer or pole dancer or stripper, very intuitive and very self-confident.

KAPLAN: What’s the role of choreography in a Masego show?

MASEGO: I just try to tap into being Jamaican. I think I just let that take over. I want to find something that’s more than just pop choreography, taking elements of dance from different regions. But for this run, I just watched Ogi. She’s the woman opening for me and she’s very intentional with her movement. I also love watching dancers on Instagram and being inspired.

KAPLAN: On your latest album, you mentioned not wanting to be famous anymore. Have you felt that while on tour?

MASEGO: I think it’s a necessary dance. Fame can be beneficial if you channel it correctly. I don’t need people to chase me or take pictures of me or bid over my clothes on eBay. I just like access to relationships and resources. And the ability to take care of my loved ones. But I feel like there’s a different word I want. It’s like the way that people look at Andre 3000. If you see him walking with the flute, you want to take a picture, but you’re gonna hesitate. You’re like, “should I be in that aura?” Appreciate from afar, maybe find some way to show what that person means to you but don’t scream and cry and faint if it’s not genuine. If it’s just because of “Hey Ya!” [then] I don’t want it.

KAPLAN: If it’s just because of “Tadow,” do you not want it?

MASEGO: I mean, part of me doesn’t. But at the end of the day, it’s still my song. It’s still my baby. Even if people are just seeing it and not knowing what’s happening, there’s a chance that there’s some depth that can be accessed.