Luke James Loves Coca-Cola, A Goofy Movie, and, Well, Love

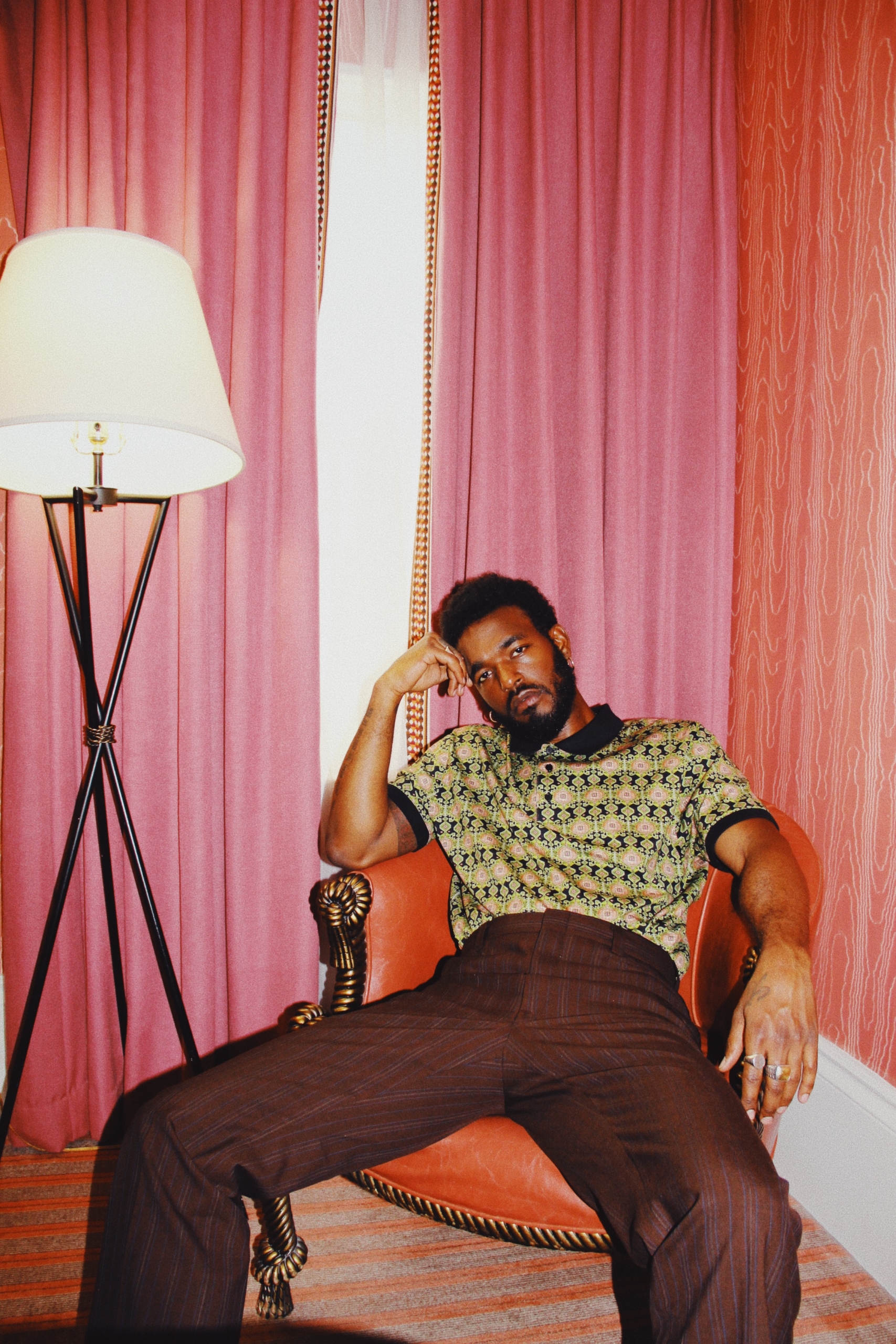

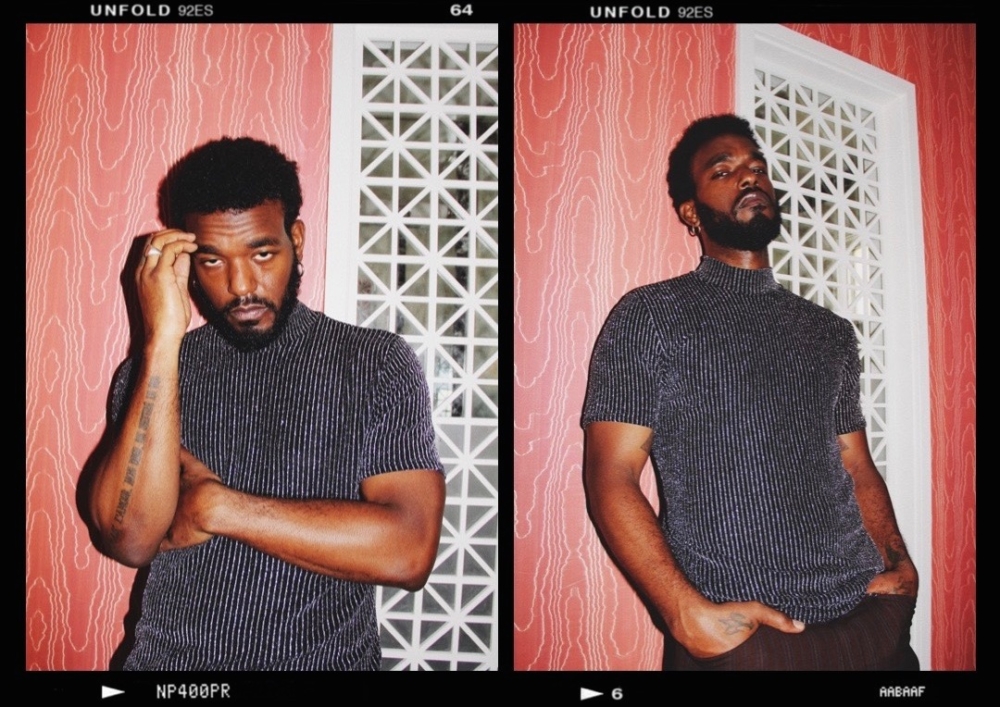

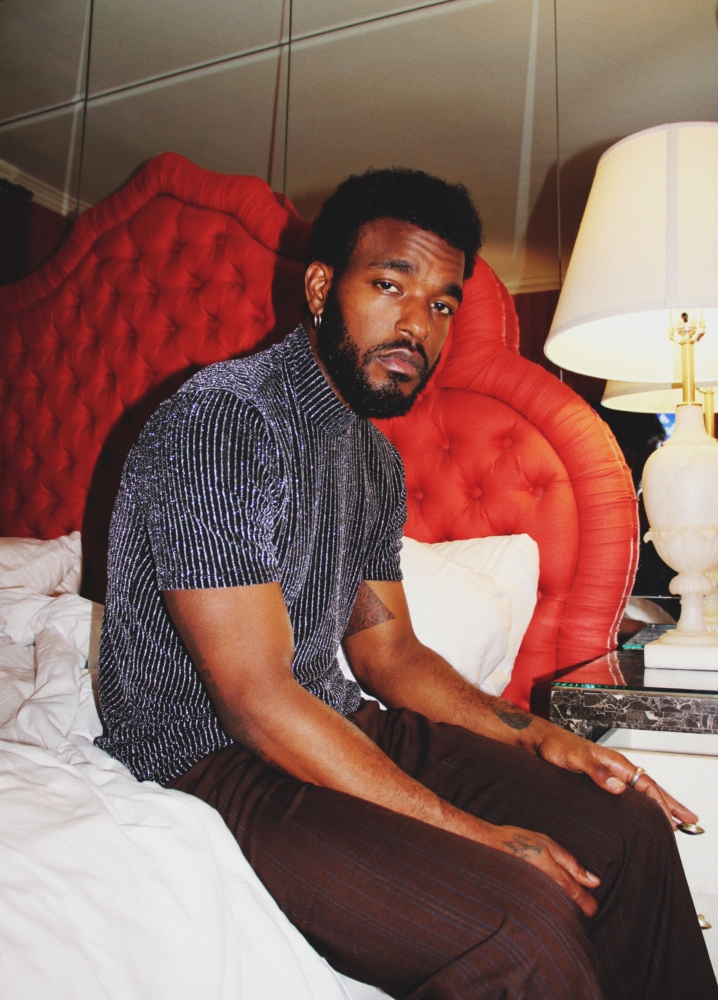

All photos by Sariel Elkaim.

Luke James wouldn’t shy away from the label of “loverboy.” “I love love,” he says with a smooth-edged laugh, ahead of the release of his new album, To Feel Love/d. “To feel loved, to feel love. That’s what everyone wants. That’s what I want, for sure.” With two Grammys under his belt and a roster of live performances that have included opening for Beyoncé and singing alongside Prince, James seems like he’s checked off all the boxes, but he’s still looking to return to that elusive destination of love. It’s that searching that makes his music so irresistible, his slow burn melodies and soft croons in line with those of his R&B heroes, Marvin Gaye, D’Angelo, and even the High Priest of Pop himself. Now set to star in the third season of Lena Waithe’s Showtime series The Chi, premiering this summer, James doesn’t seem to want to sit still. We asked James to flirt with some questions lifted from Glenn O’Brien’s legendary 1977 interview with Andy Warhol, ranging from God to Coke, from hate to—duh—love.

———

SARAH NECHAMKIN: What was the first real thing that you produced?

LUKE JAMES: My mom got this Microsoft computer and on it, it had this recorder. Basically similar to what the iPhone has, the memo thing, but on this recorder, you could reverse. That’s how I would dub myself, dub my vocals at the same time, and I would burn it to a CD and listen to it. I would just make the sounds and melodies I would hear, and I would layer vocals and make a beat and do that over and over until I had something. I think I got that concept from watching “Purple Rain.” He was playing this tape for Apollonia and it was a vocal in reverse. It was a sample of a woman crying, but he played it backwards, and it sounded like she was laughing, and in my mind I was like, “Oh wow, I have a recorder on this computer, I could sample my vocal and create what I want.” I don’t know, I was just making stuff. I wish I still had it. I probably have it on my first Apple computer that I got when I left high school. I haven’t listened to it, but I know I was making up some wild songs.

NECHAMKIN: Did you get good grades in school?

JAMES: No. I didn’t.

NECHAMKIN: Did they say you had natural talent?

JAMES: Yeah, they said I had natural talent, but they said that I was a drifter and instead of writing my notes, I was writing songs, which is true. I couldn’t stop hearing it. You hear what you hear when you’re a kid. That’s why schools need to re-evaluate the way they do things because it’s really trash in some ways, the system. It’s not nurturing. It doesn’t adhere to each child individually. It just makes us all one thing and tries to teach us the same way when some kids don’t receive it the same. Some kids’ attention spans only can last so long.

NECHAMKIN: What advice would you give to a young person who wants to become a musician?

JAMES: Study your craft. Like, in totality. Listen to everything, explore, dig. Never stop digging, never stop listening, never stop feeling. Surround yourself with like-minded people and people who are smarter than you, who you feel you can learn from. People who you’re like, “Wow, there’s a level that they’re on that I would like to get to or just be around,” and somehow you find your way to that. You take on their work ethic.

NECHAMKIN: Pepsi or Coke?

JAMES: Pepsi or… oh.

NECHAMKIN: The hardest question that I’m going to ask.

JAMES: I’m going to go with Coke because my mom loves Coke. In New Orleans, Coke is everywhere.

NECHAMKIN: Do you think that people should live in outer space?

JAMES: It sounds like that Ernie song, “I don’t want to live on the moon.” Ernie of Bert and Ernie from Sesame Street. I can’t remember the lyrics, but it’s so good. I wouldn’t like to live on the moon because I don’t want to be alone, but there’s times where I would love to. I would love to have a house there so I could get away.

NECHAMKIN: That would be cool. Vacation house on the moon.

JAMES: Yeah. When I really need to get the hell out of here, I’ll go.

NECHAMKIN: What do you like to do when you’re not working?

JAMES: Work.

NECHAMKIN: [Laughs.] Everyone says that.

JAMES: Just finding other ways. I love creating. It’s cliché, but when you love what you do, it’s not work. It’s true. When you’re an artist in totality, it’s your identity. I can’t turn it off, so I work.

NECHAMKIN: But then there’s the difference between the creating part of the job and the touring, the press. I’m sure sometimes it can inhibit the creative juices.

JAMES: It’s the stress that makes it weird. It’s the pressure of like, I’ve got to do this, when music is more, Do you want to do it? Do you feel it? Artists are artists because they don’t want the regular nine-to-five. I’ve got to do this, I’ve got to meet a quota—that type of pressure doesn’t make a diamond for us. It makes fucking rocks.

NECHAMKIN: Which is why there are a lot of rocks among the diamonds.

JAMES: There’s a lot of rocks among the diamonds.

NECHAMKIN: What do you do in the morning when you wake up?

JAMES: I roll my ankles and my feet around.

NECHAMKIN: I thought you were going to say something else.

JAMES: I roll a doobie. No, no I roll my ankles around. I’m being literal. I’m giving you my first thought. I’m trying to be as honest as possible. I walk a lot and I did hurt myself, and it just made me appreciate my joints and bones and taking care of myself, and I think also that gives me time to breathe instead of just, wake up and go, look at my phone, go, go, go, go. Get my system time to realize, we’re up, ready to go, we’re all there, everything’s working.

NECHAMKIN: How much time do you spend on the phone every day? This was written back when people actually spent time on the phone. Now it’s like…

JAMES: That’s hilarious. Well, before I had a cell phone—I remember that—I spoke on the phone maybe four hours.

NECHAMKIN: A day? Wow.

JAMES: A day. I mean, my mom was like, “Man, you better get up and go do something.” When you’re a kid, you don’t really think about the phone, but when you’re a teen, the phone is all yours, it’s life. My mom wasn’t having that. But, as an adult with a cell phone… Wow. I could probably look that up right now. [Pulls out phone.] Wait, how do I do it?

NECHAMKIN: I forgot they track it. I try to ignore it. I think it’s in your settings.

JAMES: Yeah? There we go. So far today, sheesh. Two hours 25 minutes.

NECHAMKIN: That’s not that much. But that’s so far.

JAMES: I’ve had a lot of meetings today.

NECHAMKIN: Do you believe in marriage?

JAMES: No. I don’t know about believe, but I think I don’t particularly subscribe to the institution. When I think of the initial thought of what marriage is, like in America, and what it’s kind of been pushed to make me feel like, it feels like pressure. It feels like something else rather than what it naturally should be, a union. It feels like a business agreement, and that’s weird. I’m still figuring it out. If we are constantly evolving every day…

NECHAMKIN: How can you evolve with someone else over the course of 20, 30 years?

JAMES: You know? And what happens is you have this strain, this invisible chain that you both feel like, “Oh, I can’t break it.” It’s invisible, but everyone can see the chain. And we can’t let everyone see that we’re breaking the chain.

NECHAMKIN: Have you ever been in love?

JAMES: Yes.

NECHAMKIN: That’s what the album is about, right?

JAMES: Yes. I know what that feeling is, and the album is me trying to get to that place that I once felt before. To feel loved, to feel love. That’s what everyone wants. That’s what I want, for sure. I love love.

NECHAMKIN: Did you ever hate anybody?

JAMES: Yeah, I did. I did hate someone, and that’s ugly. Someone broke my heart and that was how I decided to get through it—to hate them.

NECHAMKIN: Sometimes I feel like that’s the only way, unfortunately.

JAMES: Yeah, I got angry enough to move to New York.

NECHAMKIN: Where were you before?

JAMES: L.A. I was like, got to get the fuck out of here. They’re everywhere. They’re tethered to everything. They’re inside of the people you love. Your original tribe now has become something else, and you just got to escape that shit. In L.A., you really got to know somebody. Out here, you could be a loner. And there’s a whole tribe of loners that go hang out where the tribe of loners hang out, and you find it. It’s just endless. The city is alive. You can get lost and found in New York.

NECHAMKIN: Do you think Nixon got a raw deal? My editor wrote next to this one, “Update for 2019.”

JAMES: That is so funny. A raw deal? Man. Fuck Nixon, fuck all the motherfuckers. Fuck them. Fuck them. Bullshit, bullshit, bullshit.

NECHAMKIN: I guess you could update that for what’s going on right now and it would be not that different.

JAMES: No. Fuck him. Bruh, I don’t know. I have a weird feeling. It’s so weird, democracy and all that. What it all just says to me, very loudly, is that there’s one side that is for good, and there is a whole side that is just pure fucking evil and it wants what it wants and only what it wants, and then there’s no in-between. It’s like, fuck that. Let’s just be good and fuck these people. Killing anyone is wrong. Locking up anyone is fucked up and wrong. Kids are kids. The Earth is hurting, okay? Let’s just fuck it, fuck the money, fuck all that shit, and tell motherfuckers what the real deal is, and so motherfuckers get it in their head. We got to find other ways of doing this.

And yes, the world will go mad for a moment, but it’s what has to happen for us to survive, to live, if we truly care about life itself. I don’t dive into those things because it just makes me…

NECHAMKIN: Sad?

JAMES: Yeah.

NECHAMKIN: It feels like some of this stuff should be obvious at this point, right? Like you shouldn’t have to be saying these things.

JAMES: Right.

NECHAMKIN: What’s your favorite scent?

JAMES: I like essential oils. Women have it, especially natural hair-wearing women that just put stuff all over their hair and whatever, the natural shit, and you give them a hug, and it’s just like, “Wow, that’s so nice.” It’s just so calming. And then my second favorite scent is Jo Malone, “Pomegranate Noir.” My mom has the candle and it reminds me of her.

NECHAMKIN: What do you look at first on a woman?

JAMES: Eyes. I mean, that’s…

NECHAMKIN: Obvious.

JAMES: I’m looking at someone, everybody, in their eyes first. That’s what I grab, and that’s the connection. And then everything else trickles down.

NECHAMKIN: Did you ever see a movie that got you hot? Maybe as a kid, growing up?

JAMES: Don’t do that. Why’re we doing that?!

NECHAMKIN: [Laughs.] These aren’t my questions!

JAMES: [Laughs.] Well, shit, as a kid, let me see what got me going. I think her name was Maxine from A Very Goofy Movie. I was so in love with her. She was so cute. And I really wanted him to get her. I wanted her to fucking do the dance, “Stand Out,” Powerline and all that. It was way cool.

NECHAMKIN: Someone very recently told me he thinks A Goofy Movie has his favorite soundtrack ever.

JAMES: It’s the best. Tevin Campbell was singing most of that. I just saw a video on social media of him now performing it. I felt like a kid all over again. I had never seen him sing the song ever in life, so to see that, his older self, still singing it, still sound the same, it was amazing.

NECHAMKIN: They don’t make movies like that anymore.

JAMES: Movies now are so serious. It’s like they’re trying to make kids grow up so fast. Kids don’t care about a lot of those things, they just see … Colors are colors and love is love and people are people. If they have any animosity towards something, it’s something they saw someone older do, it’s not their initial feelings or anything. I get the reason why you put certain messages in movies. But then, I always think, “That message isn’t for the kid, it’s for the fucking adult.”

NECHAMKIN: I was noticing your ring. I really love it.

JAMES: [Shows hand.] This one is John Hardy. A big brother of mine who I really respect, he got me this ring, and he was like, “You know, you need a piece, a statement. You get older, you pass it down.”

I bruised my finger, sorry. After a show, I punched a wall. I don’t remember doing that. I was really excited after the show, and I bruised my finger. I usually rock this ring on the other hand.

NECHAMKIN: That looks painful.

JAMES: Eh.

NECHAMKIN: Do you believe in god?

JAMES: I do believe in god. That’s funny you asked me because I was asking myself that question this morning. I believe in god, I just don’t believe in some of the teachings that have been going on for people trying to alter, push their idea of what god is.

NECHAMKIN: This is funny because I feel like nobody would ask this now, but the question is, “Do you ever think about politics?” Of course, everyone thinks about politics.

JAMES: Everyone. You can’t even help it now. It’s everywhere. I try not to, though. I try to make a conscious effort of like, “Nah, I got it, I got my spiel, I know what’s going on, I need a break from it, because it’s ugly.” The pressure is intense. For me, it has to be honest. Sometimes you’re just like, “I don’t want to say shit about it.” But then that’s weak.

But I think it is important that artists be connected, because music is godly, it is from god. It is our way of relating emotions and feelings and growing. I mean, sound created the Earth, vibration, the reverberation that created life. So, I think it’s important to understand what music is. You can either build the world or you can break it. And in order to know how to do either, you have to be connected. And that is part of what you get connecting to politics and all of that.

NECHAMKIN: And connecting to people who might listen to you, who might not be from the same world view like us. But it’s a hard line to toe, I think. People don’t always like these questions directly. It’s almost like “How much money do you make?” kind of thing, which Americans are so uncomfortable with talking about.

JAMES: The funny thing is, I don’t think of it that way. Fuck money. I think about happiness and joy over money. That’s what I think about. So, who’s going to help me get to happiness and joy? That’s where I’m at with it. Not, who’s going to make sure I keep my taxes and all that kind of shit. I don’t have that mind, yet. I don’t think I’ll ever have that mind. I hope I never have that mind to think that way, the way of putting money over feeling.

NECHAMKIN: That’s the question—whether people can be more persuaded by anger or by hope and love.

JAMES: It’s interesting. But the thing is, you can’t have love and comfortability and security without money. We’re all, get this money, hustle hard, all of that, all of that. It just constant. Love hard. Get that love. Love more, love bigger, love wide, love wild. Love endlessly. If that was more of a thing, a unanimous thing, maybe evolution would change. Evolution would happen and people would let go of material things and the “me above everyone else” mentality—the “let me be the big man, sitting on the throne,” when there’s so much room in this castle for everybody.